'One Eye in Toxteth, One Eye in Croxteth' – Examining Youth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Governors' News Spring 2010

Governor Services Courses for autumn 2015 Performance Related Pay Monday 21 September 10.00am to 12noon Ref: G15/42 or Monday 21 September 6.00pm to 8.00pm Ref: G15/43 Venue: Toxteth Annexe, Aigburth Road, L17 7BN The session will cover: The Governing Board’s responsibilities Monitoring the implementation of PRP Understanding the appeals process Presenters: Katie Smith and Kath Aistrop, School Employment Advisory Team Termly Meeting for Chairs Wednesday 23 September 6.00pm to 8.00pm Ref: G15/44 Venue: Toxteth Annexe, Aigburth Road, L17 7BN This meeting is open to Chairs, or representatives, of all Governing Bodies. Councillor Nick Small, Assistant Mayor of Liverpool & Cabinet Member - Education, Employment & Skills, Councillor Lana Orr, Mayoral Lead for Primary Schooling and Colette O’Brien, Director of Children’s Services will be present at the meeting. There will be a presentation of the Director's Items for the term followed by opportunities for discussion and questions. Cost: Free Ofsted Inspections Tuesday 29 September 6.00pm to 8.00pm Ref: G15/45 or Friday 02 October 10.00am to 12noon Ref: G15/46 Venue: Toxteth Annexe, Aigburth Road, L17 7BN The session will cover: The framework for inspections The inspection process How is Governance inspected? What will the Inspectors ask me? Presenter: Dave Cadwallader, Governor Services Officer 1 11111111 Termly Meeting for Clerks Friday 18 September 10.00am to 12noon Ref: G15/41 Venue: Toxteth Annexe, Aigburth Road, L17 7BN Our termly meeting for clerks to governing boards and/or committees includes briefings and discussion on current issues as well as an opportunity to share good practice and raise queries. -

Liverpool. (Kelly S

1 380 LIVERPOOL. (KELLY S • All"xander Bros. Llm. diamond merchants, jeweUers, silver Allan Diana (Mrs.), apartments, 102 Chatham street smiths &o. 66 Lord stnet .Allan George, coal dealer, lb'2A, Rosalind street, Kirkdale Alexander & Christie, commission merchants,& agents to the .Allan George, water inspector, 34 Horsley st. Mount Vemon North British Mercantile Insurance Co. 64 South Castle .Allan Henry, librarian Incorporated Law Society of Liver- street; T A " Consign, Liverpool " pool, 13 Union Court; res. 21 George's road Alexander Robert & Co. ship owners, I9 Tower buildings .Allan Henry, secretary The Rising Provident of Liverpool north, Water st. ; T A "Alrad, Liverpool" ; Tn 623 Limited ; res. 17 Ince avenue, Litherland Alexander & Co. cotton merchants, 142 & 144 The .Albany, Allan Henry, shipwright, 63 Gill street Oldhall street; T A " Rednaxela, Linrpool " .Allan James, assistant sec. London & Lancashire Fire Insur .Alexander .Alexander, commission agent,t. 23 Lombard ance Co. 45 Dale street; res. 13 Derby park, Rock Ferry chambers, Bixteth street .Allan James H. steam ship owner, see Allan Bros. & Co AlexanderBenjamin,grocer & provision dlr.21i-iSmithdown la. Alla.n James Henry, pharmaceutical chemist, 69 Breck road; Alexander Benjamin Graham, grocer & provision dealer, 86 Everton road & 40 William Henry street ; 139 Oakfield 146 North Hill street road, Everton & 31 West Derby rood; res. 26 Fitzclarence Alexander Chas. bookkeeper, 57 Cockburn st. Toxteth park street, Everton Alexander David, inspector of works, 45 Dorothy st.Edge hl Allan Job, furn. remover, 201 Westminster road, Kirkdale Alexander Dlonysius, mariner, 2 Vronhill st. Toxteth park .Allan John, clerk, 11 Bulwer street, Everton Alexandt:r Edward, professor of gymnastics, 116 Upper Allan John, painter, 58 Fernhill street, Toxtetb park H uskisson street Allan John, tinsmith, 3 Opie street, Everton Alexander Elias, commercial traveller, 94 Harrowby street, .Allan Joseph Barnes, shipwright, 5 Sterling street, Kirkdale Toxteth park .Allan Robert G. -

First Steps Enterprise Limited & Fazakerley, Croxteth, Stoneycroft

First Steps Enterprise Limited & Fazakerley, Croxteth, Stoneycroft & Knotty Ash Children’s Centre Job Title: Activities Worker Number: 2 positions Pay: £9 per hour/16 hours per week Initially fixed term until 31st March 2020 Aims of Post • To support and deliver family & child activities (such as Rhyme Time, Stay and Play, Messy Play, Baby massage, baby weighing, physical activity sessions, Early Years Workshops, Early Support and others), which provide childcare, education, health and family support • To work as part of the centre team to deliver high quality early years services for children and families Responsible to: • Day-to-day – Centre Manager • Employer – First Steps Enterprise Managing Director Responsible for: N/a Main Responsibilities • To work as part of the children’s centre team to deliver family & child activities and creches, which provide childcare, education, health and family support • To fully support the delivery within the Early Years Foundation Stage framework and be able to deliver continuous provision • To maintain appropriate records and evaluation of sessions promoting EYFS development. • To assist in the setting up and clearing of rooms for activities, including preparing snack and creating and updating wall displays. • To work as part of the centre team to ensure a welcoming and friendly environment for children and families at all times. • To support communication and language development for children in the centre’s reach area which may require further intervention. • To provide regular feedback to parents -

Gang Rehabilitation Programs in El Salvador

Page | 1 8/25/2008 INVESTING IN YOUTH :GANG REHABILITATION FOR VIOLENCE PROGRAMS IN EL SALVADOR PREVENTION Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment to the degree M.Sc. Latin American and Caribbean Studies. Utrecht University. Institute of Development Studies. | By Alison Yule Page | 2 Contents Introduction Overview of Research Topic Project Methodology: Accessing Gang Rehabilitation as a Researcher Case Study Approach Theory of Gang Rehabilitation Gang Rehabilitation in the Context of El Salvador Overview of Existing Programs and Their Objectives Challenges to Gang Rehabilitation Observed In the Field Overcoming Obstacles: Cross Sector Analysis of Gang Rehabilitation Methods Church NGO Government The Rehabilitated Gang Member: As Survivor and Mentor Analysis of Testimonies from Rehabilitated Gang Members Conclusion Focus Group/ Participant Observation results Overall conclusions from research: Deconstructing elements of exemplary programs Personal reflections and suggestions for the future References Annexes: 1. List of organisations consulted 2.Research methodology chart 3.List of NGO and Government Gang Rehabilitation Projects 4/5. Milton Vega’s six stages to gang rehabilitation 6.Message from the MS13 and 7. Photo documentation Page | 3 ABSTRACT El Salvador’s armed conflict came to an end with Peace Accords signed in 1992 however the political war in El Salvador has now transformed into a social war. Gangs are feared as the most dangerous perpetrators of social violence. In gang communities ‘at-risk’ youth are subject to social exclusion, unemployment and domestic/street violence often joining gangs for alternative solutions. In the past, as an attempt to improve citizen security and attract voters, the government of El Salvador introduced a package of controversial anti-gang laws designed as a temporary means to criminalize gangs, violating several codes of international human rights. -

Widnes Appleton Village, Widnes

Service Name Address Postcode Monday 31st May 2021 Opening Hours Appleton Village Pharmacy - Widnes Appleton Village, Widnes WA8 6EQ 12:00- 14:00 Asda Pharmacy - West Lane - Runcorn West Lane, Runcorn WA7 2PY 09:00- 18:00 Asda Pharmacy - Widnes Road - Widnes Widnes Road, Widnes WA8 6AH 09:00- 18:00 Boots - Widnes Shopping Park - Widnes Unit 7, Widnes Shopping Park, High Street, Widnes WA8 7TN 10:00- 16:00 Tesco In Store Pharmacy - Ashley Retail Park - Widnes Ashley Gateway Retail Park, Lugsdale Road, Widnes WA8 7YT 09:00- 18:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Huyton Lane - Huyton 54-56 Huyton Lane, Huyton, Merseyside L36 7TX 09:00- 18:00 Boots - Cables Retail Park - Prescot Unit D, Block 4, Cables Retail Park, Prescot, Merseyside L34 5NQ 09:00- 18:00 Kingsway Pharmacy - Kingsway Parade - Huyton Ground Floor Shop, 5 Kingsway Parade, Huyton, Liverpool L36 2QA 10:00- 16:00 Tesco Instore Pharmacy - Cables Retail Park - Prescot Cables Retail Park, Steley Way, Prescot L34 5NQ 09:00- 18:00 Tops Pharmacy - Glovers Brow - Kirkby Units 5-6 Glovers Brow, Kirkby L32 2AE 14:00- 16:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Breck Road - Everton Breck Road, Everton, Liverpool L5 6PX 09:00- 18:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Smithdown Road - Wavertree 126 Smithdown Road, Wavertree, Liverpool L15 3JR 09:00- 18:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Speke Hall Road - Hunts Cross Unit 20, Hunts Cross Shopping Centre, Speke Hall Road, Hunts L24 9WA 09:00- Cross, Liverpool 18:00 ASDA Pharmacy - Utting Avenue - Walton Utting Avenue, Walton, Liverpool L4 9XU 09:00- 18:00 Boots - Church Street - Liverpool 9-11 Church Street, Liverpool -

LIVERPOOL INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES March 2018

LIVERPOOL INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES March 2018 Liverpool has an exciting future with £14 billion worth of investment in the pipeline. Come and join in. Liverpool – world renowned waterfront city – is currently attracting more investment happening than at any previous time in its history. Development activity is running at over £1 billion each year, in a city that has a worldwide reputation for excellence. We’re building a city with aspirations to become the most business-friendly location in the UK. We are excelling in key industries such as digital and creative. We have one of the UK’s most significant clusters of bio-sciences and a growing logistics industry located right next to the country’s newest deep water freight container terminal. We have a leisure and culture offer that not only draws in visitors from our own region but also nationally and from all over the globe. With a pipeline of £14 billion worth of schemes, there are several opportunities for investors to become involved, and for future end users to influence the type of buildings they want. This brief guide highlights some of the major schemes being led by Liverpool City Council that are happening right now or are planned, and for which investors are being sought. For more information about these and other opportunities we can help you with, please visit our website www.regeneratingliverpool.com Opportunities – Schemes seeking partners Liverpool Waters Ten Streets LOCATION: Liverpool waterfront, LOCATION: Kirkdale, North Liverpool Liverpool City Centre TOTAL SITE AREA: -

Liverpool District Local Integrated Risk Management Plan 2010/2011

APPENDIX B (CFO/057/10) Liverpool District Local Integrated Risk Management Plan 2010/2011 Contents 1. Foreword 2. Our Purpose, Aims and Core Values 3. Introduction 4. Liverpool’s Story of Place 5. Our Plans to Reduce Risk and to Address Local Priorities in Liverpool • Liverpool Community Gyms • Liverpool East Community Garden • Street Based Teams • Liverpool South Speke Community Gardens • Neighbourhood Firefighters • TAG Rugby • Healthy Watch • Generic Action Point - Fitness and Health • Generic Action Point – Corporate Social Responsibility • Generic Action Point - Carbon Footprint • Generic Action Point – Equality and Diversity 6. Conclusion 7. Appendix A Merseyside Fire & Rescue Service Local Performance Indicators. 8. Appendix B Liverpool Local Area Priority National Indicators 9. Appendix C Merseyside Fire & Rescue Service Liverpool District Management Structure. Contact Information Liverpool Management Team Position Name Email Contact District Manager Dave Mottram [email protected] 0151 296 4714 District Manager Richard Davis [email protected] 0151 296 4622 NM East Kevin Johnson NM South Ken Ross NM SouthCentral Sara Lawton NM North+City Paul Murphy NM Alt Valley Kevin Firth Liverpool 1st Rob Taylor Liverpool Fire Stations Station Address Contact 10 – Kirkdale Studholme Street, Liverpool, L20 8EQ 0151 296 5375 11 – City Centre St Anne Street, Liverpool, L3 3DS 0151 296 6250 12 – Low Hill West Derby Road, Liverpool, L6 2AE 0151 296 5415 13 – Allerton Mather Avenue, Allerton, Liverpool, L18 6HE 0151 296 -

Aigburth Park

G R N G A A O A T D B N D LM G R R AIGBURTHA PARK 5 P R I R M B T 5 R LTAR E IN D D GR G 6 R 1 I Y CO O Superstore R R O 5 V Y 7 N D 2 R S E 5 E E L T A C L 4 A Toxteth Park R E 0 B E P A E D O Wavertree H S 7 A T A L S 8 Cemetery M N F R O Y T A Y E A S RM 1 R N Playground M R S P JE N D K V 9 G E L A IC R R K E D 5 OV N K R R O RW ST M L IN E O L A E O B O A O P 5 V O W IN A U C OL AD T R D A R D D O E A S S 6 P N U E Y R U B G U E E V D V W O TL G EN T 7 G D S EN A V M N N R D 1 7 I B UND A A N E 1 N L A 5 F R S V E B G G I N L L S E R D M A I T R O N I V V S R T W N A T A M K ST E E T V P V N A C Y K V L I V A T A D S R G K W I H A D H K A K H R T C N F I A R W IC ID I A P A H N N R N L L E A E R AV T D E N W S S L N ARDE D A T W D T N E A G K A Y GREENH H A H R E S D E B T B E M D T G E L M O R R Y O T V I N H O O O A D S S I T L M L R E T A W V O R K E T H W A T C P U S S R U Y P IT S T Y D C A N N R I O C H R C R R N X N R RL T E TE C N A DO T E E N TH M 9 A 56 G E C M O U 8 ND R S R R N 0 2 A S O 5 R B L E T T D R X A A L O R BE E S A R P M R Y T Y L A A C U T B D H H S M K RT ST S E T R O L E K I A H N L R W T T H D A L RD B B N I W A LA 5175 A U W I R T Y P S R R I F H EI S M S O Y C O L L T LA A O D O H A T T RD K R R H T O G D E N D L S S I R E DRI U V T Y R E H VE G D A ER E H N T ET A G L Y R EFTO XT R E V L H S I S N DR R H D E S G S O E T T W T H CR E S W A HR D R D Y T E N V O D U S A O M V B E N I O I IR R S N A RIDG N R B S A S N AL S T O T L D K S T R T S V T O R E T R E O A R EET E D TR K A D S LE T T E P E TI S N -

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study

Liverpool Historic Settlement Study Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project December 2011 Merseyside Historic Characterisation Project Museum of Liverpool Pier Head Liverpool L3 1DG © Trustees of National Museums Liverpool and English Heritage 2011 Contents Introduction to Historic Settlement Study..................................................................1 Aigburth....................................................................................................................4 Allerton.....................................................................................................................7 Anfield.................................................................................................................... 10 Broadgreen ............................................................................................................ 12 Childwall................................................................................................................. 14 Clubmoor ............................................................................................................... 16 Croxteth Park ......................................................................................................... 18 Dovecot.................................................................................................................. 20 Everton................................................................................................................... 22 Fairfield ................................................................................................................. -

102 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

102 bus time schedule & line map 102 Fazakerley - Broadgreen View In Website Mode The 102 bus line (Fazakerley - Broadgreen) has 3 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Broadgreen: 5:05 PM - 11:05 PM (2) Fazakerley: 7:00 AM - 11:35 PM (3) Woolfall Heath: 7:05 AM - 4:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 102 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 102 bus arriving. Direction: Broadgreen 102 bus Time Schedule 54 stops Broadgreen Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 7:06 AM - 11:05 PM Monday 5:05 PM - 11:05 PM Sefton Road, Fazakerley Tuesday 5:05 PM - 11:05 PM Lower Lane, Fazakerley Wednesday 5:05 PM - 11:05 PM Aintree Hospital, Fazakerley Thursday 5:05 PM - 11:05 PM Police Station, Gillmoss Friday 5:05 PM - 11:05 PM Long Lane, Walton Saturday 5:05 PM - 11:05 PM East Lancashire Road, Norris Green West Derby Cemetery, Norris Green 102 bus Info Oakgate Close, Dog And Gun Direction: Broadgreen Stops: 54 Trip Duration: 27 min Worrow Road, Dog And Gun Line Summary: Sefton Road, Fazakerley, Lower Oakgate Close, Liverpool Lane, Fazakerley, Aintree Hospital, Fazakerley, Police Station, Gillmoss, Long Lane, Walton, East Waterstone Close, Dog And Gun Lancashire Road, Norris Green, West Derby Porchƒeld Close, Liverpool Cemetery, Norris Green, Oakgate Close, Dog And Gun, Worrow Road, Dog And Gun, Waterstone Close, Mansion Drive, Croxteth Dog And Gun, Mansion Drive, Croxteth, Stonedale Crescent, Croxteth, Stonedale Cresent, Croxteth, Stonedale Crescent, Croxteth Stonebridge Lane, Croxteth, Stonebridge Lane, -

Learning Networks

Guide to Liverpool’s Learning Networks Overview 2013-2014 Updated January 2014 and April 2014 Learning Network: B2 Co-leader (s) School Email and Phone Number Karen McBride Croxteth CP [email protected] 0151 546-3140 Elaine Spencer Broad Square [email protected] 0151 226 1117 Lead Coordinator Email Phone Number Dave Woodhouse [email protected] 07725900344 Member Schools Bankview Broad Square Croxteth Ellergreen Florence Melly Leamington Monksdown Ranworth Square Redbridge Wellesbourne Roscoe Funding Host School and Network Base St John Bosco Learning Network: B6 School Co Leader(s) Email and Phone Number Anne Pontifex St John Bosco [email protected] 0151-546-6360 Cheryl Chatburn Rice Lane Inf [email protected] 0151-525-9776 Margaret Rowlands Rice Lane Jnr [email protected] 0151-525-3356 Management Board N/A Lead Coordinator Email Phone Number Dave Woodhouse [email protected] 07725900344 Member Schools Arnot St Mary C of E Barlows De La Salle Emmaus Fazakerley High Fazakerley Primary Holy Name Longmoor Northcote Our Lady and St Philomena’s Our Lady and St Swithin’s Rice Lane Infants Rice Lane Juniors St John Bosco St Matthews Primary St Teresa of Lisieux Funding Host School and Network Base St John Bosco Learning Network: D4 Co-leader (s) School Email and Phone Number Jeremy Barnes All Saints [email protected] 263 9561 Catholic Primary Clare Drew Williams Anfield Infants [email protected] -

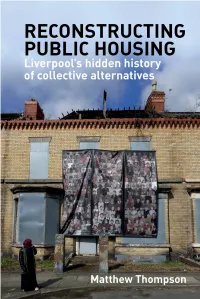

Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’S Hidden History of Collective Alternatives

Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives Reconstructing Public Housing Liverpool’s hidden history of collective alternatives Reconstructing Public Housing Matthew Thompson LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2020 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2020 Matthew Thompson The right of Matthew Thompson to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available ISBN 978-1-78962-108-2 paperback eISBN 978-1-78962-740-4 Typeset by Carnegie Book Production, Lancaster An Open Access edition of this book is available on the Liverpool University Press website and the OAPEN library. Contents Contents List of Figures ix List of Abbreviations x Acknowledgements xi Prologue xv Part I Introduction 1 Introducing Collective Housing Alternatives 3 Why Collective Housing Alternatives? 9 Articulating Our Housing Commons 14 Bringing the State Back In 21 2 Why Liverpool of All Places? 27 A City of Radicals and Reformists 29 A City on (the) Edge? 34 A City Playing the Urban Regeneration Game 36 Structure of the Book 39 Part II The Housing Question 3 Revisiting