A Critical Analysis of Governance Structures Within Supporter Owned Football Clubs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wimbledon FC to Milton Keynes This Summer Is a Critical Moment in London’S Football History

Culture, Sport and Tourism Away from home Scrutiny of London’s Football Stadiums June 2003 Culture, Sport and Tourism Away from home Scrutiny of London’s Football Stadiums June 2003 copyright Greater London Authority June 2003 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 1 85261 496 1 Cover photograph credit EMPICS Sports Photo Agency This publication is printed on recycled paper Chair’s Foreword The move by Wimbledon FC to Milton Keynes this summer is a critical moment in London’s football history. This move prompted the London Assembly’s Culture, Sport and Tourism committee to look into the issue of redevelopment for London clubs. With Fulham and Brentford yet to secure new stadiums for their clubs and question marks remaining over Arsenal’s and Tottenham’s grounds the issue is a live one. We do not want to see more clubs leave London. During the 2002/03 season about 5 million fans watched professional football in London. In addition, hundreds of thousands of Londoners participate every year in club sponsored community projects and play football. This report seeks to ensure that this added value isn’t lost to Londoners. We did not set out to judge local situations but to tease out lessons learnt by London football clubs. Football is more than just a business: the ties that a club has with its area and the fans that live or come from there are great. We recommend that more clubs have supporters on their board and applaud the work of Supporters Direct in rejuvenating the links between clubs and their fan base. -

Leigh Centurions V ROCHDALE HORNETS

Leigh Centurions SUvN DRAOY C17HTDH AMLAREC H O20R1N9 @ET 3S PM # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB engage with the fans at games and to see the players acknowledged for their efforts at the Toronto game, despite the narrowness of the defeat, was something Welcome to Leigh Sports Village for day 48 years ago. With a new community that will linger long in the memory. this afternoon’s Betfred stadium in the offing for both the city’s Games are coming thick and fast at FChamRpionshOip gameM agains t oTur HfootbEall team s iTt could Oalso welPl also be present and the start of our involvement in friends from Rochdale Hornets. the last time Leigh play there. the Corals Challenge Cup and the newly- Carl Forster is to be commended for It’s great to see the Knights back on the instigated 1895 Cup and the prospect of taking on the dual role of player and coach up after years in the doldrums and to see playing at Wembley present great at such a young age and after cutting his interest in the professional game revived opportunities and goals for Duffs and his teeth in two years at Whitehaven, where under James Ford’s astute coaching. players. The immediate task though is to he built himself a good reputation, he now Watching York back at their much-loved carry on the good form in a tight and has the difficult task of preserving Wiggington Road ground was always one competitive Championship where every Hornets’ hard-won Championship status in of the best away days in the season and I win is hard-earned and valuable. -

The O Cial Magazine of Rugby League Cares January 2017

The O cial Magazine of Rugby League Cares January 2017 elcome to the fi rst edition of One n ll n the ne name for Rugby League Cares’ W ne-look nesletter hich has gone through something of a transformation at the end of hat has been another busy year for the charity As you can see, we have rebranded and changed the format so that our members and supporters can get a clearer understanding of the breadth of work we do throughout the sport. In this edition we welcome a number of new partners who have recently joined the charity to assist our work, particularly the support we provide to former and current players in all levels of the game. All Sport Insurance and Purple Travel have come on board as members of the newly-formed Rugby League Cares Business Club which aims to provide a wide range of services that help players, particularly in areas where the nature of their occupation can put them at a disadvantage. 2016 proved to be a challenging year for the charity as we continued to play an important role in assisting players successfully transitioning from the sport by awarding education and welfare grants. We enjoyed a very successful partnership with Rugby AM and the Jane Tomlinson Appeal on the Ride to Rio challenge; and we secured grants from Curious Minds and Cape UK to support club foundations to deliver some life-affi rming experiences for young people in their communities via a Cultural Welcome Partnership programme. This culminated in which will deliver great outcomes for our Finally, I hope you enjoy this new version some terrifi c dance performances at maor benefi ciaries and which is easy for the public of the newsletter and catching up about all events during the year. -

Leigh Centurions V DEWSBURY RAMS

Leigh Centurions EASTERv M DONEDWAYS 2B2NUDR AYPR RILA 20M1S9 @ 3PM # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB # LEYTHERS # OURTOWNOURCLUB# OURTOWNOURCLUB warming and further proof of just what an important role Leigh Centurions plays in our local community. Over 3,000 people had a great day. This Easter Monday afternoon we achievement and Jonny Pownall on his Gregg McNally joined the Hundred Club extend a warm welcome to the one hundred games for his hometown after his early try, celebrated with a FplayerRs, officOials anMd suppo rteTrs of Hclub. E TOP trademark swallow dive and grin saw him Dewsbury Rams to LSV. The sun shone and there was some become only the 11th player in Leigh Dewsbury are coached by a former Leigh fantastic rugby played with some great history to score 100 tries for the club. player in Lee Greenwood, who scored 24 tries, Barrow contributing to the game fully We’re hoping to invite some of the tries in 28 games for the club in 2006 and and finishing strongly. In Premier Club members of that elite club to the game earned heritage number #1257. It doesn’t John Duffy and his assistants Paul today to help mark Gregg’s fabulous seem 13 years ago since Lee was playing Anderson and brother Jay gave fascinating achievement. Jonny Pownall went into the for Leigh and after a distinguished playing insights into the build-up and preparation Easter programme on 99 career tries and career he’s now making a reputation as a for the game and after the game Man of Jake Emmitt is closing in on 250 career coach and got the Dewsbury job after a the Match Iain Thornley spoke brilliantly appearances, so the milestones keep long apprenticeship as coach to Siddal and explained how much he is enjoying appearing. -

Sunday 23Rd August 1998 K.O. 3.15Pm at MOUNT PLEASANT

RUGBY LEAGUE DIVISION TWO BATLEY BULLDOGS vOLDHAM Sunday 23rd August 1998 K.O. 3.15pm at MOUNT PLEASANT BAXLEY’S MATCH SPONSOR The Reporter Group -Batley News Recommend and use balls and boots supplied by:- J A M E S G I L B E R T L t d . 5St. Matthews Street, Rugby CV21 3BY Telephone: (01788) 542426 Uellington BATLEY BEST DISCO PUB IN TOWN PjSectafi^nl t^la finne/>y^ Friday-Saturday-Sunday AGENT FOR MATCHMATES & ROMANTIQUE Silver, Ruby. Gold and Diamond Wedding Anniversay invitations a Mpn-Fri I speciality, also 18th, 21st surprise IHome12Cooking to 2pm II party and other functional invites 40 Enfield Drive, AFriendly Batley, WF17 8DY fromIan and Alison Tel: 01924-470704 TEL: 01924 473030 Take home catalogues Programme Design -Barry Trueman -Art &Type Tel: 01924 455885 Programme Pre-Press Reproduction &Printing by -Art &Type Tel: 01924 455885 % Good afternoon everyone right boots scoring 6goals. It and we welcome all was agood solid Directors, players and performance from everyone supporters from Oldham to both in attack and defence. Mount Pleasant, Batley. Well donel Today Is areal crunch game On Sunday against with both sides seeking Workington we always looked victory. Oldham will be after the better side and in the end revenge after adefeat in the won convincingly. Trans Pennine Cup Final and Unfortunately Macca picked awin for us will take Batley up agroin injury and is likely one point ahead of Oldham in to be out for the rest of the the promotion battle. I season. The team travelled believe afriendship was up and stayed overnight on Batley R.L.F.C. -

Comunicado Oficial Nº 1

COMUNICADO OFICIAL Nº 1 ASSOCIAÇÃO DE FUTEBOL DE LISBOA APROVADO EM REUNIÃO DE DIREÇÃO DE 30 DE JUNHO DE 2021 NORMAS E INSTRUÇÕES ÉPOCA 2021/2022 ÍNDICE CAPÍTULO 1 GENERALIDADES 1.1 ÉPOCA OFICIAL 1.2 HORÁRIO DE FUNCIONAMENTO DOS SERVIÇOS DA AFL 1.3 CORRESPONDÊNCIA COM A AFL 1.4 TABELA DE EMOLUMENTOS DA AFL CAPÍTULO 2 CLUBES E EQUIPAS 2.1.1 FILIAÇÃO - PROCESSO DE INÍCIO DE ÉPOCA 2.1.2 INSCRIÇÃO EM PROVAS 2.2 QUOTA DE FILIAÇÃO E INSCRIÇÃO EM PROVAS CAPÍTULO 3 PROCESSO DE INSCRIÇÃO, REVALIDAÇÃO E TRANSFERÊNCIA DE JOGADORES 3.1 CONDIÇÕES GERAIS 3.2 REGULAMENTAÇÃO CAPÍTULO 4 JOGADORES – CATEGORIAS, PARTICIPAÇÃO, PRAZOS DE INSCRIÇÕES 4.1 CATEGORIAS 4.2 PROVAS E JOGOS EM QUE OS JOGADORES PODEM PARTICIPAR 4.3 PRAZOS DE INSCRIÇÕES Pág.1 CAPÍTULO 5 JOGADORES – QUOTAS DE INSCRIÇÃO CAPÍTULO 6 JOGADORES CAPÍTULO 7 INSCRIÇÕES DE AGENTES DESPORTIVOS CAPÍTULO 8 JOGADORES E AGENTES DESPORTIVOS EMISSÃO DE CARTÕES CAPÍTULO 9 INSTRUÇÕES SOBRE A ORGANIZAÇÃO DOS JOGOS 10.1 HORÁRIO DOS JOGOS E ALTERAÇÕES 10.2 ALTERAÇÕES DE JOGOS – PROCEDIMENTOS 10.3 BOLAS FUTEBOL DE ONZE, FUTEBOL DE NOVE, FUTEBOL DE SETE E FUTSAL 10.4 REQUISIÇÃO DE FORÇAS DE SEGURANÇA 10.5 ORGANIZAÇÃO FINANCEIRA CAPÍTULO 10 CONTATOS DOS SERVIÇOS DA AFL CAPÍTULO 11 ANEXOS CAPÍTULO 12 DOCUMENTOS ASSOCIADOS Pág.2 CAPÍTULO 1 GENERALIDADES 1.1 ÉPOCA OFICIAL 2021/2022 A época oficial 2021-22 decorrerá de 01 de Julho de 2021 a 30 de Junho de 2022. 1.2 HORÁRIO DE FUNCIONAMENTO DOS SERVIÇOS DA AFL 1.2.1 Os serviços da Associação de Futebol de Lisboa têm os seguintes horários de atendimento: De Segunda a Sexta-Feira: Manhãs: 09:00 às 12:00 horas; Tardes: 13:30 às 16:00 horas. -

Comunicado Oficial Nº 1

COMUNICADO OFICIAL Nº 1 ASSOCIAÇÃO DE FUTEBOL DE LISBOA APROVADO EM REUNIÃO DE DIREÇÃO DE 30 DE JUNHO DE 2021 NORMAS E INSTRUÇÕES ÉPOCA 2021/2022 ÍNDICE CAPÍTULO 1 GENERALIDADES 1.1 ÉPOCA OFICIAL 1.2 HORÁRIO DE FUNCIONAMENTO DOS SERVIÇOS DA AFL 1.3 CORRESPONDÊNCIA COM A AFL 1.4 TABELA DE EMOLUMENTOS DA AFL CAPÍTULO 2 CLUBES E EQUIPAS 2.1.1 FILIAÇÃO - PROCESSO DE INÍCIO DE ÉPOCA 2.1.2 INSCRIÇÃO EM PROVAS 2.2 QUOTA DE FILIAÇÃO E INSCRIÇÃO EM PROVAS CAPÍTULO 3 PROCESSO DE INSCRIÇÃO, REVALIDAÇÃO E TRANSFERÊNCIA DE JOGADORES 3.1 CONDIÇÕES GERAIS 3.2 REGULAMENTAÇÃO CAPÍTULO 4 JOGADORES – CATEGORIAS, PARTICIPAÇÃO, PRAZOS DE INSCRIÇÕES 4.1 CATEGORIAS 4.2 PROVAS E JOGOS EM QUE OS JOGADORES PODEM PARTICIPAR 4.3 PRAZOS DE INSCRIÇÕES Pág.1 CAPÍTULO 5 JOGADORES – QUOTAS DE INSCRIÇÃO CAPÍTULO 6 JOGADORES CAPÍTULO 7 INSCRIÇÕES DE AGENTES DESPORTIVOS CAPÍTULO 8 JOGADORES E AGENTES DESPORTIVOS EMISSÃO DE CARTÕES CAPÍTULO 9 INSTRUÇÕES SOBRE A ORGANIZAÇÃO DOS JOGOS 10.1 HORÁRIO DOS JOGOS E ALTERAÇÕES 10.2 ALTERAÇÕES DE JOGOS – PROCEDIMENTOS 10.3 BOLAS FUTEBOL DE ONZE, FUTEBOL DE NOVE, FUTEBOL DE SETE E FUTSAL 10.4 REQUISIÇÃO DE FORÇAS DE SEGURANÇA 10.5 ORGANIZAÇÃO FINANCEIRA CAPÍTULO 10 CONTATOS DOS SERVIÇOS DA AFL CAPÍTULO 11 ANEXOS CAPÍTULO 12 DOCUMENTOS ASSOCIADOS Pág.2 CAPÍTULO 1 GENERALIDADES 1.1 ÉPOCA OFICIAL 2021/2022 A época oficial 2021-22 decorrerá de 01 de Julho de 2021 a 30 de Junho de 2022. 1.2 HORÁRIO DE FUNCIONAMENTO DOS SERVIÇOS DA AFL 1.2.1 Os serviços da Associação de Futebol de Lisboa têm os seguintes horários de atendimento: De Segunda a Sexta-Feira: Manhãs: 09:00 às 12:00 horas; Tardes: 13:30 às 16:00 horas. -

RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1

rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 RFL Official Guide 201 2 rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 2 The text of this publication is printed on 100gsm Cyclus 100% recycled paper rfl official guide 2012 working.e$S:RL GUIDE 2006 FRIDAY PM 17/1/12 14:40 Page 1 CONTENTS Contents RFL B COMPETITIONS Index ........................................................... 02 B1 General Competition Rules .................. 154 RFL Directors & Presidents ........................... 10 B2 Match Day Rules ................................ 163 RFL Offices .................................................. 10 B3 League Competition Rules .................. 166 RFL Executive Management Team ................. 11 B4 Challenge Cup Competition Rules ........ 173 RFL Council Members .................................. 12 B5 Championship Cup Competition Rules .. 182 Directors of Super League (Europe) Ltd, B6 International/Representative Community Board & RFL Charities ................ 13 Matches ............................................. 183 Past Life Vice Presidents .............................. 15 B7 Reserve & Academy Rules .................. 186 Past Chairmen of the Council ........................ 15 Past Presidents of the RFL ............................ 16 C PERSONNEL Life Members, Roll of Honour, The Mike Gregory C1 Players .............................................. 194 Spirit of Rugby League Award, Operational Rules C2 Club Officials ..................................... -

Results 25.09.2021.-26.09.2021

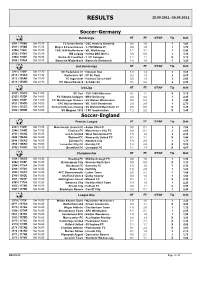

RESULTS 25.09.2021.-26.09.2021. Soccer-Germany Bundesliga HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2301 | 1358B Sat 15:30 FC Union Berlin - DSC Arminia Bielefeld 0:0 1:0 1 1,65 2303 | 1358D Sat 15:30 Bayer 04 Leverkusen - 1. FSV Mainz 05 0:0 1:0 1 1,70 2305 | 1358F Sat 15:30 TSG 1899 Hoffenheim - VfL Wolfsburg 1:1 3:1 1 2,50 2302 | 1358C Sat 15:30 RB Leipzig - Hertha BSC Berlin 3:0 6:0 1 1,30 2304 | 1358E Sat 15:30 Eintracht Frankfurt - 1. FC Cologne 1:1 1:1 X 3,75 2306 | 1359A Sat 18:30 Borussia M'gladbach - Borussia Dortmund 1:0 1:0 1 3,20 2nd Bundesliga HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2311 | 1359F Sat 13:30 SC Paderborn 07 - Holstein Kiel 1:0 1:2 2 3,65 2313 | 135AC Sat 13:30 Karlsruher SC - FC St. Pauli 0:2 1:3 2 2,85 2312 | 135AB Sat 13:30 FC Ingolstadt - Fortuna Düsseldorf 0:0 1:2 2 2,00 2314 | 135AD Sat 20:30 FC Hansa Rostock - Schalke 04 0:1 0:2 2 2,30 3rd Liga HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2323 | 135CF Sat 14:00 SC Verl - TSV 1860 München 0:1 1:1 X 3,75 2325 | 135DF Sat 14:00 FC Viktoria Cologne - MSV Duisburg 2:0 4:2 1 2,45 2326 | 135EF Sat 14:00 FC Wurzburger Kickers - SV Wehen Wiesbaden 0:0 0:4 2 2,40 2321 | 135CD Sat 14:00 1 FC Kaiserslautern - VfL 1899 Osnabrück 2:0 2:0 1 2,70 2322 | 135CE Sat 14:00 Eintracht Braunschweig - SV Waldhof Mannheim 07 0:0 0:0 X 3,25 2324 | 135DE Sat 14:00 SV Meppen 1912 - 1 FC Saarbrucken 1:2 2:2 X 3,40 Soccer-England Premier League HT FT OT/AP Tip Odd 2347 | 1369F Sat 13:30 Manchester United FC - Aston Villa FC 0:0 0:1 2 7,00 2346 | 1369E Sat 13:30 Chelsea FC - Manchester City FC 0:0 0:1 2 2,60 2351 | 136AE Sat 16:00 Leeds United - West -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Thursday Volume 540 9 February 2012 No. 264 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Thursday 9 February 2012 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2012 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through The National Archives website at www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/information-management/our-services/parliamentary-licence-information.htm Enquiries to The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] 451 9 FEBRUARY 2012 452 House of Commons Gaming Machines 2. Mr Don Foster (Bath) (LD): What estimate he has Thursday 9 February 2012 made of the number of category B2 gaming machines in operation in the UK. [94331] The House met at half-past Ten o’clock The Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Culture, Olympics, Media and Sport (John Penrose): The latest version of the Gambling Commission’s six-monthly PRAYERS industry statistics was published in December 2011. It showed that the number of category B2 gaming [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] machines—fixed odds betting terminals, or FOBTs, as they are sometimes known—in operation in Great Britain as at 31 March 2011 was 32,007. Oral Answers to Questions Mr Foster: I am most grateful to the Minister for that answer. The FOBTs he refers to, through which punters can lose £100 a spin or £18,000 a year, have been described as the crack cocaine of gambling. As he said, CULTURE, MEDIA AND SPORT numbers are exploding: some 32,000 such machines are in easily accessed high street betting shops, yet the The Secretary of State for Culture, Olympics, Media evidence shows that they are causing real damage to and Sport was asked— individuals and families, including some of the poorest people in our communities. -

An Examination of the Corporate Structures of European Football Clubs

PLAYING FAIR IN THE BOARDROOM: AN EXAMINATION OF THE CORPORATE STRUCTURES OF EUROPEAN FOOTBALL CLUBS Ryan Murphy† I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 410 II. UEFA FINANCIAL FAIR PLAY RULES ..................................................... 411 III. SPANISH SOCIO MODEL ........................................................................ 415 A. FC Barcelona ............................................................................... 415 B. Real Madrid ................................................................................. 419 C. S.A.D.s ......................................................................................... 423 IV. GERMAN MODEL .................................................................................. 423 A. The Traditional Structure (e.V.) .................................................. 424 B. AGs ............................................................................................. 425 C. GmbHs ......................................................................................... 427 D. KGaAs ......................................................................................... 428 VI. ENGLISH MODELS ................................................................................ 431 A. The Benefactor Model .................................................................. 431 1. Chelsea ................................................................................ 431 2. Manchester City .................................................................. -

Master Bibliography for Sports in Society, 1994–2009

1 MASTER BIBLIOGRAPHY Sports In Society: Issues & Controversies, 1994–2015 (5,089 references) Jay Coakley This bibliography is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. CSPS Working Papers may be distributed or cited as long as the author(s) is/are appropriately credited. CSPS Working Papers may not be used for commercial purposes or modified in any way without the permission of the author(s). For more information please visit: www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. 60 Minutes; ―Life after the NFL: Happiness.‖ Television program, (2004, December); see also, www.cbsnews.com/stories/2004/12/16/60minutes/main661572.shtml. AAA. 1998. Statement on ―Race.‖ Washington, DC: American Anthropological Association. www.aaanet.org/stmts/racepp.htm (retrieved June, 2005). AAHPERD. 2013. Maximizing the benefits of youth sport. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 84(7): 8-13. Abad-Santos, Alexander. 2013. Everything you need to know about Steubenville High's football 'rape crew'. The Atlantic Wire (January 3): http://www.theatlanticwire.com/national/2013/01/steubenville-high-football-rape- crew/60554/ (retrieved 5-22-13). Abdel-Shehid, Gamal, & Nathan Kalman-Lamb. 2011. Out of Left Field: Social Inequality and Sport. Black Point, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing Abdel-Shehid, Gamal. 2002. Muhammad Ali: America‘s B-Side. Journal of Sport and Social Issues 26, 3: 319–327. Abdel-Shehid, Gamal. 2004. Who da man?: black masculinities and sporting cultures. Toronto: Canadian Scholars‘ Press. www.cspi.org. Abney, Roberta. 1999. African American women in sport. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 70(4), 35–38.