Margaret Rutherford, Alistair Sim, Eccentricity and the British

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

Christopher Plummer

Christopher Plummer "An actor should be a mystery," Christopher Plummer Introduction ........................................................................................ 3 Biography ................................................................................................................................. 4 Christopher Plummer and Elaine Taylor ............................................................................. 18 Christopher Plummer quotes ............................................................................................... 20 Filmography ........................................................................................................................... 32 Theatre .................................................................................................................................... 72 Christopher Plummer playing Shakespeare ....................................................................... 84 Awards and Honors ............................................................................................................... 95 Christopher Plummer Introduction Christopher Plummer, CC (born December 13, 1929) is a Canadian theatre, film and television actor and writer of his memoir In "Spite of Myself" (2008) In a career that spans over five decades and includes substantial roles in film, television, and theatre, Plummer is perhaps best known for the role of Captain Georg von Trapp in The Sound of Music. His most recent film roles include the Disney–Pixar 2009 film Up as Charles Muntz, -

Terror, Trauma and the Eye in the Triangle: the Masonic Presence in Contemporary Art and Culture

TERROR, TRAUMA AND THE EYE IN THE TRIANGLE: THE MASONIC PRESENCE IN CONTEMPORARY ART AND CULTURE Lynn Brunet MA (Hons) Doctor of Philosophy November 2007 This work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I hereby certify that the work embodied in this Thesis is the result of original research, which was completed subsequent to admission to candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signature: ……………………………… Date: ………………………….. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has been generously supported, in terms of supervision, teaching relief and financial backing by the University of Newcastle. Amongst the individuals concerned I would like to thank Dr Caroline Webb, my principal supervisor, for her consistent dedication to a close reading of the many drafts and excellent advice over the years of the thesis writing process. Her sharp eye for detail and professional approach has been invaluable as the thesis moved from the amorphous, confusing and sometimes emotional early stages into a polished end product. I would also like to thank Dr Jean Harkins, my co- supervisor, for her support and feminist perspective throughout the process and for providing an accepting framework in which to discuss the difficult material that formed the subject matter of the thesis. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

Trustees' Annual Report

BFF TRUSTEE REPORT 2014_trustees report 24/02/2015 08:49 Page 1 TRUSTEES’ ANNUAL REPORT THE BORN FREE FOUNDATION LIMITED TRUSTEES’ ANNUAL REPORT & AUDITED GROUP FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2014 The Born Free Foundation is a Charity Number 1070906 Company Number 3603432 Charitable Company Limited by Guarantee BFF TRUSTEE REPORT 2014_trustees report 24/02/2015 08:49 Page 2 CONTENTS Reference and administrative details 1 Chair’s introduction 2 Structure governance & management 3 Objectives & activities 4-5 Strategic report Achievements & performance 6-11 Financial review 12-13 Plans for the future 12 Risk management 13 Statement of Trustees’ responsibilities 13 Independent auditor’s report 14 Financial statements Group statement of financial activities 15-16 Group balance sheet 17 Company balance sheet 18 Group cash flow statement 19 Notes to the financial statements 20-30 Cover Photo garyrobertsphotograpy.com BFF TRUSTEE REPORT 2014_trustees report 24/02/2015 08:49 Page 3 REFERENCE & ADMINISTRATIVE DETAILS Name The Born Free Foundation Limited Status Born Free is a charitable company limited by guarantee. Its governing document is a Memorandum and Articles of Association Charity Registration Number 1070906 Company Registration Number 3603432 Principal Office and Registered Address Broadlands Business Campus, Langhurstwood Road, Horsham RH12 4QP Website www.bornfree.org.uk Trustees Michael Reyner (Chair) Adam Batty Rosamund Kidman Cox Michael Drake Peter Ellis Virginia McKenna OBE Andrew Newton (retired 18 March 2014) -

What Are They Doing There? : William Geoffrey Gehman Lehigh University

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Theses and Dissertations 1989 What are they doing there? : William Geoffrey Gehman Lehigh University Follow this and additional works at: https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gehman, William Geoffrey, "What are they doing there? :" (1989). Theses and Dissertations. 4957. https://preserve.lehigh.edu/etd/4957 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • ,, WHAT ARE THEY DOING THERE?: ACTING AND ANALYZING SAMUEL BECKETT'S HAPPY DAYS by William Geoffrey Gehman A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Committee of Lehigh University 1n Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts 1n English Lehigh University 1988 .. This thesis 1S accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. (date) I Professor 1n Charge Department Chairman 11 ACD01fLBDGBNKNTS ., Thanks to Elizabeth (Betsy) Fifer, who first suggested Alan Schneider's productions of Samuel Beckett's plays as a thesis topic; and to June and Paul Schlueter for their support and advice. Special thanks to all those interviewed, especially Martha Fehsenfeld, who more than anyone convinced the author of Winnie's lingering presence. 111 TABLB OF CONTBNTS Abstract ...................•.....••..........•.•••••.••.••• 1 ·, Introduction I Living with Beckett's Standards (A) An Overview of Interpreting Winnie Inside the Text ..... 3 (B) The Pros and Cons of Looking for Clues Outside the Script ................................................ 10 (C) The Play in Context .................................. -

Set in Scotland a Film Fan's Odyssey

Set in Scotland A Film Fan’s Odyssey visitscotland.com Cover Image: Daniel Craig as James Bond 007 in Skyfall, filmed in Glen Coe. Picture: United Archives/TopFoto This page: Eilean Donan Castle Contents 01 * >> Foreword 02-03 A Aberdeen & Aberdeenshire 04-07 B Argyll & The Isles 08-11 C Ayrshire & Arran 12-15 D Dumfries & Galloway 16-19 E Dundee & Angus 20-23 F Edinburgh & The Lothians 24-27 G Glasgow & The Clyde Valley 28-31 H The Highlands & Skye 32-35 I The Kingdom of Fife 36-39 J Orkney 40-43 K The Outer Hebrides 44-47 L Perthshire 48-51 M Scottish Borders 52-55 N Shetland 56-59 O Stirling, Loch Lomond, The Trossachs & Forth Valley 60-63 Hooray for Bollywood 64-65 Licensed to Thrill 66-67 Locations Guide 68-69 Set in Scotland Christopher Lambert in Highlander. Picture: Studiocanal 03 Foreword 03 >> In a 2015 online poll by USA Today, Scotland was voted the world’s Best Cinematic Destination. And it’s easy to see why. Films from all around the world have been shot in Scotland. Its rich array of film locations include ancient mountain ranges, mysterious stone circles, lush green glens, deep lochs, castles, stately homes, and vibrant cities complete with festivals, bustling streets and colourful night life. Little wonder the country has attracted filmmakers and cinemagoers since the movies began. This guide provides an introduction to just some of the many Scottish locations seen on the silver screen. The Inaccessible Pinnacle. Numerous Holy Grail to Stardust, The Dark Knight Scottish stars have twinkled in Hollywood’s Rises, Prometheus, Cloud Atlas, World firmament, from Sean Connery to War Z and Brave, various hidden gems Tilda Swinton and Ewan McGregor. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

A Dictionary of Literary and Thematic Terms, Second Edition

A DICTIONARY OF Literary and Thematic Terms Second Edition EDWARD QUINN A Dictionary of Literary and Thematic Terms, Second Edition Copyright © 2006 by Edward Quinn All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Quinn, Edward, 1932– A dictionary of literary and thematic terms / Edward Quinn—2nd ed. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-8160-6243-9 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Criticism—Terminology. 2. Literature— Terminology. 3. Literature, Comparative—Themes, motives, etc.—Terminology. 4. English language—Terms and phrases. 5. Literary form—Terminology. I. Title. PN44.5.Q56 2006 803—dc22 2005029826 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can fi nd Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfi le.com Text design by Sandra Watanabe Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America MP FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents Preface v Literary and Thematic Terms 1 Index 453 Preface This book offers the student or general reader a guide through the thicket of liter- ary terms. -

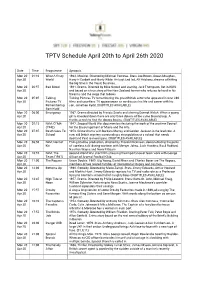

TPTV Schedule April 20Th to April 26Th 2020

TPTV Schedule April 20th to April 26th 2020 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 20 01:10 What A Crazy 1963. Musical. Directed by Michael Carreras. Stars Joe Brown, Susan Maughan, Apr 20 World Harry H Corbett and Marty Wilde. An East End lad, Alf Hitchens, dreams of hitting the big time in the music business. Mon 20 02:55 Bad Blood 1981. Drama. Directed by Mike Newell and starring Jack Thompson. Set in WW2 Apr 20 and based on a true story of the New Zealand farmer who refuses to hand in his firearms and the siege that follows. Mon 20 05:05 Talking Talking Pictures TV remembering the great British actor who appeared in over 240 Apr 20 Pictures TV films and countless TV appearances as we discuss his life and career with his Remembering son, Jonathan Kydd. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Sam Kydd Mon 20 06:00 Emergency 1962. Drama directed by Francis Searle and starring Dermot Walsh. When a young Apr 20 girl is knocked down there are only three donors of the same blood group. A frantic search to find the donors begins. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 20 07:15 IWM: CEMA 1942. Second World War documentary featuring the work of the wartime Council Apr 20 (1942) for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts. Mon 20 07:35 Death Goes To 1953. Crime drama with Barbara Murray and Gordon Jackson in the lead role. A Apr 20 School rare, old British mystery surrounding a strangulation at a school that needs Scotland Yard to investigate. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 20 08:50 IWM: Next of Ealing Studios production, directed by Thorold Dickinson, demonstrating the perils Apr 20 Kin of 'careless talk' during wartime, with Mervyn Johns, Jack Hawkins, Basil Radford, Naunton Wayne and Nova Pilbeam. -

Venustheatre

VENUSTHEATRE Dear Member of the Press: Thank you so much for coverage of The Speed Twins by Maureen Chadwick. I wanted to cast two women who were over 60 to play Ollie and Queenie. And, I'm so glad I was able to do that. This year, it's been really important for me to embrace comedy as much as possible. I feel like we all probably need to laugh in this crazy political climate. Because I thought we were losing this space I thought that this show may be the last for me and for Venus. It turns out the new landlord has invited us to stay and so, the future for Venus is looking bright. There are stacks of plays waiting to be read and I look forward to spending the summer planning the rest of the year here at Venus. This play is a homage, in some ways, to The Killing of Sister George. I found that script in the mid-nineties when it was already over 30 years old and I remember exploring it and being transformed by the archetypes of female characters. To now be producing Maureen's play is quite an honor. She was there! She was at the Gateway. She is such an impressive writer and this whole experience has been very dierent for Venus, and incredibly rewarding. I hope you enjoy the show. All Best, Deborah Randall Venus Theatre *********************************************** ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT PERFORMANCES: receives about 200 play submissions and chooses four to produce in the calendar year ahead. Each VENUSTHEATRE Maureen Chadwick is the creator and writer of a wide range of award-winning, critically acclaimed and May 3 - 27, 2018 production gets 20 performances. -

Lyrics and Music

Soundtrack for a New Jerusalem Lyrics and Music By Lily Meadow Foster and Toliver Myers EDITED by Peter Daniel The 70th Anniversary of the National Health Service 1 Jerusalem 1916 England does not have a national anthem, however unofficially the beautiful Jerusalem hymn is seen as such by many English people. Jerusalem was originally written as a preface poem by William Blake to his work on Milton written in 1804, the lyrics were added to music written by Hubert Parry in 1916 during the gloom of WWI when an uplifting new English hymn was well received and needed. Blake was in- spired by the mythical story Jesus, accompanied by Joseph of Arimathea, once came to England. This developed its major theme that of creating a heaven on earth in En- galnd, a fairer more equal country that would abolish the exploitation of working people that was seen in the ‘dark Satin mills’ of the Industrial revolution. The song was gifted by Hubert Parry to the Suffragette movement who were inspired by this vi- sion of equality. 2 Jerusalem William Blake lyrics Hubert Parry Music 1916 And did those feet in ancient time Walk upon England's mountains green? And was the holy Lamb of God On England's pleasant pastures seen? And did the countenance divine Shine forth upon our clouded hills? And was Jerusalem builded here Among those dark Satanic Mills? Bring me my bow of burning gold! Bring me my arrows of desire! Bring me my spear! O clouds, unfold! Bring me my chariot of fire! I will not cease from mental fight Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand Till we have built Jerusalem In England's green and pleasant Land Hubert Parry 1916 Words by William Blake 1804 3 Jerusalem 1916 4 Jerusalem 1916 5 Jerusalem 1916 William Blake imagined a time when Britain would be a fairer more equal society.