Inventive Practices and Ordered Informality in the Functioning of the District Courts in Niamey and Zinder (Niger)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIGER: Carte Administrative NIGER - Carte Administrative

NIGER - Carte Administrative NIGER: Carte administrative Awbari (Ubari) Madrusah Légende DJANET Tajarhi /" Capital Illizi Murzuq L I B Y E !. Chef lieu de région ! Chef lieu de département Frontières Route Principale Adrar Route secondaire A L G É R I E Fleuve Niger Tamanghasset Lit du lac Tchad Régions Agadez Timbuktu Borkou-Ennedi-Tibesti Diffa BARDAI-ZOUGRA(MIL) Dosso Maradi Niamey ZOUAR TESSALIT Tahoua Assamaka Tillabery Zinder IN GUEZZAM Kidal IFEROUANE DIRKOU ARLIT ! BILMA ! Timbuktu KIDAL GOUGARAM FACHI DANNAT TIMIA M A L I 0 100 200 300 kms TABELOT TCHIROZERINE N I G E R ! Map Doc Name: AGADEZ OCHA_SitMap_Niger !. GLIDE Number: 16032013 TASSARA INGALL Creation Date: 31 Août 2013 Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS 84 Gao Web Resources: www.unocha..org/niger GAO Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1: 5 000 000 TILLIA TCHINTABARADEN MENAKA ! Map data source(s): Timbuktu TAMAYA RENACOM, ARC, OCHA Niger ADARBISNAT ABALAK Disclaimers: KAOU ! TENIHIYA The designations employed and the presentation of material AKOUBOUNOU N'GOURTI I T C H A D on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion BERMO INATES TAKANAMATAFFALABARMOU TASKER whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations BANIBANGOU AZEY GADABEDJI TANOUT concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area ABALA MAIDAGI TAHOUA Mopti ! or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its YATAKALA SANAM TEBARAM !. Kanem WANZERBE AYOROU BAMBAYE KEITA MANGAIZE KALFO!U AZAGORGOULA TAMBAO DOLBEL BAGAROUA TABOTAKI TARKA BANKILARE DESSA DAKORO TAGRISS OLLELEWA -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR12228 Implementation Status & Results Niger Transport Sector Program Support Project (P101434) Operation Name: Transport Sector Program Support Project (P101434) Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 11 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 26-Nov-2013 Country: Niger Approval FY: 2008 Public Disclosure Authorized Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Sector Investment and Maintenance Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Board Approval Date 29-Apr-2008 Original Closing Date 15-Dec-2012 Planned Mid Term Review Date 14-Feb-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 24-Apr-2013 Public Disclosure Copy Effectiveness Date 10-Sep-2008 Revised Closing Date 15-Dec-2015 Actual Mid Term Review Date 28-Jan-2011 Project Development Objectives Project Development Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) The project development objectives are to (i) improve the physical access of rural population to markets and services on selected unpaved sections of the national road network, and (ii) strengthen the institutional framework, management and implementation of roadmaintenance in Niger. Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost 1. Periodic maintenance and spot rehabilitation of unpaved roads; 24.89 2. Institutional support to main transport sector players 2. Institutional support to the main transport sector players 5.11 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Moderately Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Moderate Moderate Public Disclosure Authorized Implementation Status Overview As of October 31, 2013, the Grant amount for the original project has reached a disbursement rate of about 100 percent. -

Caught in the Middle a Human Rights and Peace-Building Approach to Migration Governance in the Sahel

Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar CRU Report Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin Caught in the middle A human rights and peace-building approach to migration governance in the Sahel Fransje Molenaar Jérôme Tubiana Clotilde Warin CRU Report December 2018 December 2018 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: © Jérôme Tubiana. Unauthorized use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Fransje Molenaar is a Senior Research Fellow with Clingendael’s Conflict Research Unit, where she heads the Sahel/Libya research programme. She specializes in the political economy of (post-) conflict countries, organized crime and its effect on politics and stability. -

Download File

NIGER: COVID-19 Situation Report – #09 22 June to 20 July 2020 Situation in Numbers 1,105 COVID-19 confirmed cases 69 deaths 6,25% Lethality rate @UNICEFNiger/J.Haro (Ministère de la Santé Publique, July 20th, Situation Overview and Humanitarian Needs 2020) As of the end of the reporting period, Niger registered 1,105 cases of COVID-19, 1,014 3,800,000 patients healed, 69 deaths, 9,197 followed contacts, with a decreasing trend in cases. Children affected Even if the rate of imported cases is high, local transmission is still active. 4 out of 8 by COVID-19 regions didn’t report any cases for at least 2 weeks. UNICEF works closely with the Government and its partners to respond to the ongoing outbreak in the country, which is school reopening already facing the consequences of multiple crisis (nutrition, conflicts, natural disasters). As part of the national COVID-19 response plan, UNICEF is providing technical support to the government of Niger to scale-up the national safety net program to mitigate the social and economic impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on the most vulnerable population, US$ 25.8 M with a special focus on children and women needs. UNICEF continues to support the back funding required to school activities by providing the Ministry of Education with Education and WASH supplies, technical assistance, key messages about COVID-19 prevention and a monitoring system based on RapidPro. UNICEF assists particularly the Ministry of Health (MoH), in the field of risk communication/community engagement (RCCE), infection prevention and control (IPC), supply and logistics, epidemiological surveillance and healthcare provision and it is co-leading 3 of the 8 sub-committees established by the MoH (RCCE, IPC and logistics) at central and sub-national level. -

WHO Emergency Health Programme for the Food Crisis in Niger Situation Report # 13 1 to 7 November 2005

Health action in crisis WHO Emergency Health Programme for the Food Crisis in Niger Situation Report # 13 1 to 7 November 2005 I. Highlights • A project for 79 000 Euros, for expansion of the current national communicable diseases surveillance system to include nutritional surveillance through the timely collection of data on malnutrition and analysis for appropriate response in Niger, was submitted to the Humanitarian Aid Department of the European Commission (ECHO) by the WHO Niger Representative. • WHO and partners are scheduling additional training courses for healthcare workers on the treatment of malnutrition from all eight regions of Niger (Agadez, Diffa, Dosso, Maradi, Niamey, Tahoua, Tilla- bery and Zinder) to respond to increased requests. It was planned to provide training for 450 health- care workers by the end 31 December 2005. This has already been exceeded. By 7 November, 503 healthcare workers had received training. Of the 503, 48 participated in the training for healthcare trainers on the treatment of malnutrition and 455 participated in training on the treatment of malnutri- tion. • The WHO collaborating centre, Burlo-Garofolo Regional Paediatric Hospital Institute of Child Health, Trieste, Italy, seconded a paediatric-nurse to WHO Niger for the period of one month from the 4 No- vember 2005. The paediatric-nurse is based at the Tillaberi Hospital and Intensive Nutritional Reha- bilitation Centre and will provide technical support to paramedical personnel in charge of the treat- ment of children under five years suffering from severe malnutrition upon request of the local authorities. • Partners of the interagency group on nutrition provided an update of activities at the weekly coordina- tion meeting held at UNICEF on 4 November 2005. -

Local Governance Opportunities for Sustainable Migration Management in Agadez

Local governance opportunities for sustainable migration management in Agadez Fransje Molenaar CRU Report Anca-Elena Ursu Bachirou Ayouba Tinni Supported by: Local governance opportunities for sustainable migration management in Agadez Fransje Molenaar Anca-Elena Ursu Bachirou Ayouba Tinni CRU Report October 2017 October 2017 © Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’. Cover photo: Men sitting on a bench at the Agadez Market. © Boris Kester / traveladventures.org Unauthorised use of any materials violates copyright, trademark and / or other laws. Should a user download material from the website or any other source related to the Netherlands Institute of International Relations ‘Clingendael’, or the Clingendael Institute, for personal or non-commercial use, the user must retain all copyright, trademark or other similar notices contained in the original material or on any copies of this material. Material on the website of the Clingendael Institute may be reproduced or publicly displayed, distributed or used for any public and non-commercial purposes, but only by mentioning the Clingendael Institute as its source. Permission is required to use the logo of the Clingendael Institute. This can be obtained by contacting the Communication desk of the Clingendael Institute ([email protected]). The following web link activities are prohibited by the Clingendael Institute and may present trademark and copyright infringement issues: links that involve unauthorized use of our logo, framing, inline links, or metatags, as well as hyperlinks or a form of link disguising the URL. About the authors Fransje Molenaar is a research fellow at the Clingendael Institute’s Conflict Research Unit Anca-Elena Ursu is a research assistant at the Clingendael Institute’s Conflict Research Unit Bachirou Ayouba Tinni is a PhD student at the University of Niamey The Clingendael Institute P.O. -

Ref Agadeza1.Pdf

REGION D'AGADEZ: Carte référentielle Légende L i b y e ± Chef lieu de région Chef lieu de département localité Route principale Route secondaire ou tertiaire Frontière internationale Frontière régionale Cours d'eau MADAMA Région d'Agadez A l g é r i e ☶ Population Djado DJABA DJADO CHIRFA KANARIA I-N-AZAOUA SARA BILMA DAOTIMMI I-N-TADERA ☶ 17 459 TOUARET SEGUEDINE IFEROUANE TAGHAJIT TAMJIT TAZOUROUTETASSOS INTIKIKITENE OURARENE AGALANGAÏ ☶ 32 864 DOUMBA EZAZAW FARAZAKAT ANEY ASSAMAKKA ABARGOT TEZIRZEK LOTEY TCHOUGOY TIRAOUENE TAKARATEMAMANAT ZOURIKA EMI TCHOUMA AZATRAYA AGREROUM ET TCHWOUN ARLIT Gougaram ACHENOUMA IFEROUANE ISSAWANE ARRIGUI Dirkou ACHEGOUR TEMET DIRKOU ☶ 103 369 INIGNAOUEI TILALENE ARAKAW MAGHET TAKRIZA TARHMERT ARLIT AGAMGAM BILMA ANOU OUACHCHERENE TCHIGAYEN TAZOURAT TAGGAFADI Dannet GOUGARAM SIDAOUET ZOMO ASSODE IBOUL TCHILHOURENE ERISMALAN TIESTANE Bilma MAZALALE AJIWA INNALARENE TAZEWET AGHAROUS ESSELEL ZOBABA ANOUZAGHARAN DANNET FAYAYE Timia FACHI TIGUIR AJIR IMOURAREN TIMIA FACHI MARI Fachi TAKARACHE ZIKAT OFENE MALLETAS AKEREBREB ABELAJOUAD TCHINOUGOUWENEARITAOUA IN-ABANGHARIT TAMATEDERITTASSEDET ASSAK HARAU INTAMADE T c h a d EGHARGHAR TILIA OOUOUARI Dabaga ELMEKI BOURNI TIDEKAL SEKIRET ASSESA MERIG AKARI TELOUES EGANDAWEL AOUDERAS EOULEM SOGHO TAGAZA ATKAKI TCHIROZERINE TABELOT EGHOUAK M a l i AZELIK DABLA ABARDOKH TALAT INGAL IMMASSATANE AMAN NTEDENT ELDJIMMA ☶ 241 007 GUERAGUERA TEGUIDDA IN TESSOUM ABAZAGOR Tabelot FAGOSCHIA DABAGA TEGUIDDA IN TAGAIT I-N-OUTESSANE ☶ EKIZENGUI AGALGOU 51 818 TCHIROZERINE INGOUCHIL -

Tahaoua Abalak Bagaroua Birni Nkonni Bouza Illela Keita Madaoua Malbaza Tahouha Tassara Tchintabaraden Tillia

Niger: Atlas admin1 Agadez Tahaoua Agadez Tahaoua Aderbissinat Abalak Arlit Bagaroua Birma Birni Nkonni Iferouane Bouza Ingall Illela Tcirozerine Keita Madaoua Diffa Malbaza Diffa Tahouha Bosso Tassara Goudou Maria Tchintabaraden Maine Soroa Tillia Ngourti Nguigmi Tillabéri Agadez Tillabéri Dosso Abala Dosso Ayerou Boboye Balleyara Dioundiou Banbangou Dogondoutchi Banikilare Falmey Filingue Gaya Goteheye Loga Kollo Diffa Tibiri Ouallam Tahoua Say Maradi Tera Tillabéri Zinder Maradi Torodi Aguie Maradi Bermo Zinder Niamey Dakoro Zinder Dosso Gazaoua Beledji Guidan Roumdji Ayerou Madarounfa Damagaram Takaya Mayahi Dungass Tessaoua Goure Kantche Niamey Magara Niamey Mirriah Tafeita Tanout Niger: Reference map of Agadez ! Fort Gardel !! Ghat ! ! Al Quatrun Eferi ! Al Wigh LIBYA ! Ami Madema In-Amdjel ! ! Ain az Zan ! Tamanraset !! ALGERIA Bardaa !! Djado Creation date: 02/05/2018 ! TIBESTI Data soures: OCHA, ESRI, UNCS, Zouar DCW, IGNN ! Paper size: A4 Iferouane Bilma Disclaimers The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on these maps do not Garin Malam ! Arlit imply official endorsement CHAD or acceptance by the Iferouane Dirkou ! ! United Nations. Arlit Bilma ! ! KIDAL 0 100 200 Dannet km ! Timia Fachi ! ! Tchirozerine ! Ingall Tabelot BORKOU Tchirozerine ! ^! ! National capital Tassara Ingall ! GAO ! ! Agadez !! Admin1 capital Tillia Aderbissinat ! ! DIFFA Main town ! Tamaya INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES TAHOUA !Aderbissinat Abalak ! N'Gourti ADMIN1 BOUNDARIES ZINDER ! Tesker ! KANEM Admin2 boundaries Abala Tahoua ! Tanout ! !! TILLABERI Nokou Main road Bouza ! Filingue ! ! ! Illela N'Guigmi MARADI ! Mao Secondary road Goure LAC !! Malbaza! Mayahi Sofoua ! ! Liwa! Local road !! Zinder Goudoumaria Bosso ! ! ! ! ! ! !! !! !! ! Niger: Reference map of Diffa ! Bilma TIBESTI AGADEZ BORKOU Creation date: 02/05/2018 Data soures: OCHA, ESRI, UNCS, DCW, IGNN Paper size: A4 N'Gourti Disclaimers The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on these maps do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the CHAD United Nations. -

Usaid Humanitarian Assistance to Niger for Malnutrition and Food Insecurity in Fy 2010

USAID HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO NIGER FOR MALNUTRITION AND FOOD INSECURITY IN FY 2010 0°KEY 2° 4° 6° 8° 10° 12° 14° 16° USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP 0 200 400 mi LIBYA FOR C IN MA I TI PH O A N Agriculture and Food Security Tamanrasset 0 200 400 600 km R U A G NIGER N O I T E C Economic Recovery and Market Systems G U S A A D Emergency Food Assistance ID F y Madama /DCHA/O 22° Food Vouchers Affected Areas b Humanitarian Air Service OCHA B UNHAS Humanitarian Coordination and b B Information Management UNICEF Djado Zouar 5 Local Food Procurement and Distribution CRS, CARE, & HKI Consortium y Logistics and Relief Commodities ALGERIA WFP 5 Séguedine a20° y 20° Nutrition Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene J I-n-Guezzâm AGADEZ 07/14/10 Assamakka Mercy Corps CJ Dirkou Arlit Bilma MALI AGADEZ 18° Timia Fachi 18° TILLABÉRI CRS Teguidda-n- A Tessoumt Mercy Corps 5 Oxfam/GB Tassara 7 Agadez DIFFA AC Ingal VSF/B HKI Gao AC WFP C TAHOUA CPI y 16° 16° WV Ménaka Concern N C ZINDER ig e DIFFA r CRS FAO A Aderbissinat CRS Termit- Mercy Corps A Kaoboul 5 Njourti TAHOUA FAO A Bani Bangou HKI CHAD Yatakala Tahoua Abalak Ayorou Tânout IFRC Bagaroua Keïta Bankilaré CPI y Tillabéry Ouallam Filingué Dakoro ZINDER Illéla Bouza Nguigmi Mao 14° Téra 14° TILLABÉRI MARADI Gouré Baléyara Madaoua Lake Chad Dargol Dogondoutchi Tessaoua Niamey Birnin Zinder Maradi Bol 7 DOSSO Konni Maïné Diffa BURKINA Birnin DOSSO ima Yob R Soroa u Say Gaouré CRS ug FASO A MARADI d Niamey Dosso a Sokoto Magaria m HKI Nguru Komadugu o C CRS K AM IFRC Katsina A E o S R t ok a La Tapoa IFRCo o d O Kantchari k t d O Mercy o o Oxfam/GBKaura a a Dioundiou S AC an g N Corps C Namoda G N Birnin Kebbi gu SC/UK u N C d ig Zamfara Original Map Courtesy of the UN CartographicN'Djamena Section e Gusau ia a 12° r ej m C 12° Diapaga Gaya WV ad o NIGERIA Fada- Kano H K The boundaries and names used on thish map do a r Ngourma Dutse not imply official endorsement or acceptancei 0° 2° BENIN 4°Ka 6° 8° 10° 12°by the U.S. -

Regreening in the Maradi and Zinder Regions of Niger

Copyright © 2011 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Sendzimir, J., C. P. Reij, and P. Magnuszewski. 2011. Rebuilding resilience in the Sahel: regreening in the Maradi and Zinder regions of Niger. Ecology and Society 16(3):1. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04198-160301 Research, part of a Special Feature on Resilience and Vulnerability of Arid and Semi-Arid Social Ecological Systems Rebuilding Resilience in the Sahel: Regreening in the Maradi and Zinder Regions of Niger Jan Sendzimir 1, Chris P. Reij 2, and Piotr Magnuszewski 3 ABSTRACT. The societies and ecosystems of the Nigerien Sahel appeared increasingly vulnerable to climatic and economic uncertainty in the late twentieth century. Severe episodes of drought and famine drove massive livestock losses and human migration and mortality. Soil erosion and tree loss reduced a woodland to a scrub steppe and fed a myth of the Sahara desert relentlessly advancing southward. Over the past two decades this myth has been shattered by the dramatic reforestation of more than 5 million hectares in the Maradi and Zinder Regions of Niger. No single actor, policy, or practice appears behind this successful regreening of the Sahel. Multiple actors, institutions and processes operated at different levels, times, and scales to initiate and sustain this reforestation trend. We used systems analysis to examine the patterns of interaction as biophysical, livelihood, and governance indicators changed relative to one another during forest decline and rebound. It appears that forest decline was reversed when critical interventions helped to shift the direction of reinforcing feedbacks, e.g., vicious cycles changed to virtuous ones. -

Type of the Paper (Article

Supplementary material Supplementary Table 1. Departmental flood statistics (SA = settlements affected; PA = people affected; HD = houses destroyed; CL = crop losses (ha); LL = livestock losses Y = number of years with almost a flood). CL LL DEPARTMENT REGION SA PA HD YEARS (ha) (TLU) 2007; 2009; 2012; 2013; ABALA TILLABERI 54 22263 1140 151 1646 2015 ABALAK TAHOUA 1 4437 570 52 6 2011 ADERBISSINAT AGADEZ 8 15931 223 1 2382 2010; 2013 2001; 2010; 2013; 2014; AGUIE MARADI 36 14420 1384 158 3 2015 2005; 2007; 2009; 2010; ARLIT AGADEZ 34 9085 166 19 556 2011; 2013; 2015 AYEROU TILLABERI 8 3430 25 197 2480 2008; 2010; 2012 BAGAROUA TAHOUA 25 9780 251 0 28 2014; 2015 2006; 2010; 2011; 2012; BALLEYARA TILLABERI 41 14446 13 2697 2 2014 BANIBANGOU TILLABERI 7 1400 154 204 3574 2006; 2010; 2012 BANKILARE TILLABERI 0 0 0 0 0 BELBEDJI ZINDER 1 553 5 0 0 2010 BERMO MARADI 10 12281 73 0 933 2010; 2014; 2015 BILMA AGADEZ 0 0 0 0 0 1999; 2006; 2008; 2014; BIRNI NKONNI TAHOUA 27 28842 343 274 1 2015 1999; 2000; 2003; 2006; 2008; 2009; 2010; 2011; BOBOYE DOSSO 159 30208 3412 2685 1 2012; 2013; 2014; 2015; 2016 BOSSO DIFFA 13 2448 414 24 0 2007; 2012 BOUZA TAHOUA 9 2070 303 28 0 2007; 2015 2001; 2010; 2012; 2013; DAKORO MARADI 20 15779 728 59 2 2014; 2015 DAMAGARAM 2002; 2009; 2010; 2013; ZINDER 13 10478 876 777 596 TAKAYA 2014 DIFFA DIFFA 23 2856 271 0 0 1999; 2010; 2012; 2013 DIOUNDIOU DOSSO 55 14621 1577 1660 0 2009; 2010; 2012; 2013 1999; 2002; 2003; 2005; 2006; 2008; 2009; 2010; DOGONDOUTCHI DOSSO 128 52774 3245 577 23 2012; 2013; 2014; 2015; 2016 -

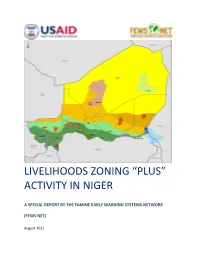

Livelihoods Zoning “Plus” Activity in Niger

LIVELIHOODS ZONING “PLUS” ACTIVITY IN NIGER A SPECIAL REPORT BY THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2011 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 4 National Livelihoods Zones Map ................................................................................................................... 6 Livelihoods Highlights ................................................................................................................................... 7 National Seasonal Calendar .......................................................................................................................... 9 Rural Livelihood Zones Descriptions ........................................................................................................... 11 Zone 1: Northeast Oases: Dates, Salt and Trade ................................................................................... 11 Zone 2: Aïr Massif Irrigated Gardening ................................................................................................ 14 Zone 3 : Transhumant and Nomad Pastoralism .................................................................................... 17 Zone 4: Agropastoral Belt .....................................................................................................................