Social Movements and Contentious Politics, Revised and Updated Third

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Mass

A Theory of the Critical Mass. I. Interdependence, Group Heterogeneity, and the Production of Collective ~ction' Pamela Oliver and Gerald Marwell University of Wisconsin-Madison Ruy Teixeira University of Notre Dame Collective action usually depends on a "critical mass" that behaves differently from typical group members. Sometimes the critical mass provides some level of the good for others who do nothing, while at other times the critical mass pays the start-up costs and induces widespread collective action. Formal analysis supple- mented by simulations shows that the first scenario is most likely when the production function relating inputs of resource contri- butions to outputs of a collective good is decelerating (characterized by diminishing marginal returns), whereas the second scenario is most likely when the production function is accelerating (character- ized by increasing marginal returns). Decelerating production func- tions yield either surpluses of contributors or order effects in which contributions are maximized if the least interested contribute first, thus generating strategic gaming and competition among potential contributors. The start-up costs in accelerating production func- tions create severe feasibility problems for collective action, and contractual or conventional resolutions to collective dilemmas are most appropriate when the production function is accelerating. INTRODUCTION This article extends the formal theory of collective action to define and specify the role of the critical mass. For a physicist, the "critical mass" is ' This research was supported by the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation. The authors wish to thank Erik Olin Wright, Elizabeth Thomson, John Lemke, and the reviewers of this Journal for their comments on an earlier version of this article. -

Daily Eastern News: August 27, 2018 Eastern Illinois University

Eastern Illinois University The Keep August 2018 8-27-2018 Daily Eastern News: August 27, 2018 Eastern Illinois University Follow this and additional works at: https://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2018_aug Recommended Citation Eastern Illinois University, "Daily Eastern News: August 27, 2018" (2018). August. 7. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/den_2018_aug/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the 2018 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in August by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOUSING AND DINING VOLLEYBALL RECORD Eastern’s housing and dining staff work with students to establish a smooth start Eastern’s volleyball team had a 2-2 record this past weekend, finishing to the semester. the Panther Invitational in third place. PAGE 3 PAGE 8 HE T Monday, August 27,aily 2018 astErn Ews D E“TELL THE TRUTH AND DON’T BE AFRAID” n VOL. 103 | NO. 6 CELEBRATING A CENTURY OF COVERAGE EST. 1915 WWW.DAILYEASTERNNEWS.COM Phishy business: Students receive spam from people they know Staff Report | @DEN_News Beneath the green box there is more text that states the “message has been delayed” and Phishing emails and spam have been sent gives a date. to several students with a panthermail email Josh Reinhart, Eastern’s public informa- address from people they know Sunday night. tion coordinator, said the emails might have The emails contain a subject line that re- reached a sizeable population of people with lates to the person receiving the email, and an [email protected] email address. -

The New York City Draft Riots of 1863

University of Kentucky UKnowledge United States History History 1974 The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 Adrian Cook Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Cook, Adrian, "The Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863" (1974). United States History. 56. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_united_states_history/56 THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS This page intentionally left blank THE ARMIES OF THE STREETS TheNew York City Draft Riots of 1863 ADRIAN COOK THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY ISBN: 978-0-8131-5182-3 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-80463 Copyright© 1974 by The University Press of Kentucky A statewide cooperative scholarly publishing agency serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky State College, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank Contents Acknowledgments ix -

Transient Solidarities: Commitment and Collective Action in Post-Industrial Societies Charles Heckscher and John Mccarthy

bs_bs_banner British Journal of Industrial Relations doi: 10.1111/bjir.12084 52:4 December 2014 0007–1080 pp. 627–657 Transient Solidarities: Commitment and Collective Action in Post-Industrial Societies Charles Heckscher and John McCarthy Abstract Solidarity has long been considered essential to labour, but many fear that it has declined. There has been relatively little scholarly investigation of it because of both theoretical and empirical difficulties. This article argues that solidarity has not declined but has changed in form, which has an impact on what kinds of mobilization are effective. We first develop a theory of solidarity general enough to compare different forms. We then trace the evolution of solidarity through craft and industrial versions, to the emergence of collaborative solidarity from the increasingly fluid ‘friending’ relations of recent decades. Finally, we examine the question of whether these new solidarities can be mobilized into effective collective action, and suggest mechanisms, rather different from tra- ditional union mobilizations, that have shown some power in drawing on friending relations: the development of member platforms, the use of purposive campaigns and the co-ordination of ‘swarming’ actions. In the best cases, these can create collective actions that make a virtue of diversity, openness and participative engagement, by co-ordinating groups with different foci and skills. 1. Introduction In the last 30 years, there is every evidence that labour solidarity has weak- ened across the industrialized world. Strikes have widely declined, while the most effective recent movements have been fundamentalist and restrictive — turning back to traditional values and texts, narrowing the range of inclusion. -

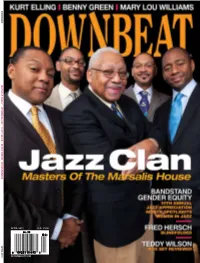

Downbeat.Com April 2011 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. PRIL 2011 DOWNBEAT.COM A D OW N B E AT MARSALIS FAMILY // WOMEN IN JAZZ // KURT ELLING // BENNY GREEN // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2011 APRIL 2011 VOLume 78 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Maureen Flaherty ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, -

The Transnational Dimension of Protest: from the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street

The transnational dimension of protest: From the Arab Spring to Occupy Wall Street Donatella della Porta (European University Institute) and Alice Mattoni (University of Pittsburgh) This workshop is supported by the Standing Group on Participation and Mobilization ABSTRACT The workshop intends to analyze the transnational dimension in the recent wave of global protests like the Arab Spring, the European Indignados, and Occupy Wall Street. Literature on transnational social movements flourished in the last decades, exploring social movement networks that organized counter-summits demonstrations and social forums meetings. Most recent protests across the world had, amongst their target, national governments and policies. But they also maintained a strong transnational stance. Starting from a comparative perspective, the workshop focuses on the transnational mechanisms and processes at work in the Arab Spring, the European Indignados, and Occupy Wall Street by paying particular attention to 1) imageries and practices of democracy and 2) communication and mediation processes. OUTLINE In the past years, massive protests developed in several countries across the world. Late in 2010 and early in 2011, social movement for democracy flourished in many Arab countries: from Tunisia, Egypt and Libya to Yemen, Syria and Bahrain. In the Spring 2011, protesters initiated peaceful mobilizations in the streets and squares of many European countries, amongst which Portugal, Spain, Italy and Greece. At the beginning of Autumn 2011, some activists in the U.S.A. occupied Zuccotti Park, in the Wall Street District of New York. Some weeks later, Occupy Wall Street protests spread in many other cities across the U.S.A. and other countries, like the U.K. -

Cultural Approaches in the Sociology of Social Movements 61

Book_Roggeband&Klandermans_0387709592_proof1_110407 01 02 03 04 CHAPTER 3 05 06 07 08 Cultural Approaches in the 09 10 Sociology of Social Movements 11 12 13 JAMES M. JASPER 14 15 16 17 18 19 In the late twentieth century, the social sciences underwent a broad cultural turn, building on 20 an earlier linguistic turn (Lafont 1993) but finding human meanings in a variety of activities 21 and artifacts not previously interpreted as cultural. Cognitive psychology played the vanguard 22 role in this shift, but practitioners in all disciplines were soon able to find indigenous tradi- 23 tions and tools that helped them craft their own repertories for understanding meaning (e.g., 24 Crane 1994; Hunt 1989; Kuper 1999). Beginning in the 1970s, increasing numbers of social 25 scientists began to pay attention to how humans understand the world, and not simply their 26 (supposedly) objective behaviors and outcomes within it. 27 The cultural turn left its mark on the study of politics and social movements. Interestingly, 28 it was more often those who studied culture who were able to see the politics behind it (Crane 29 1994); students of politics were slower to see the culture inside it (Jasper 2005). French post- 30 structuralists such as Derrida and Foucault saw politics in all institutions and cultural artifacts 31 (Dosse 1997) long before mainstream political scientists and sociologists recognized the mean- 32 ings that permeate political institutions and actions. 33 The gap between more structural and more cultural approaches to mobilization often 34 depended on how scholars who had been politically active in and around 1968 interpreted the 35 barriers they had faced, especially whether they felt their intended revolutionary subjects had 36 had the correct consciousness or not. -

IV. Fabric Summary 282 Copyrighted Material

Eastern State Penitentiary HSR: IV. Fabric Summary 282 IV. FABRIC SUMMARY: CONSTRUCTION, ALTERATIONS, AND USES OF SPACE (for documentation, see Appendices A and B, by date, and C, by location) Jeffrey A. Cohen § A. Front Building (figs. C3.1 - C3.19) Work began in the 1823 building season, following the commencement of the perimeter walls and preceding that of the cellblocks. In August 1824 all the active stonecutters were employed cutting stones for the front building, though others were idled by a shortage of stone. Twenty-foot walls to the north were added in the 1826 season bounding the warden's yard and the keepers' yard. Construction of the center, the first three wings, the front building and the perimeter walls were largely complete when the building commissioners turned the building over to the Board of Inspectors in July 1829. The half of the building east of the gateway held the residential apartments of the warden. The west side initially had the kitchen, bakery, and other service functions in the basement, apartments for the keepers and a corner meeting room for the inspectors on the main floor, and infirmary rooms on the upper story. The latter were used at first, but in September 1831 the physician criticized their distant location and lack of effective separation, preferring that certain cells in each block be set aside for the sick. By the time Demetz and Blouet visited, about 1836, ill prisoners were separated rather than being placed in a common infirmary, and plans were afoot for a group of cells for the sick, with doors left ajar like others. -

King Mob Echo: from Gordon Riots to Situationists & Sex Pistols

KING MOB ECHO FROM 1780 GORDON RIOTS TO SITUATIONISTS SEX PISTOLS AND BEYOND BY TOM VAGUE INCOMPLETE WORKS OF KING MOB WITH ILLUSTRATIONS IN TWO VOLUMES DARK STAR LONDON ·- - � --- Printed by Polestar AUP Aberdeen Limited, Rareness Rd., Altens Industrial Estate, Aberdeen AB12 3LE § 11JJJDJJDILIEJMIIENf1r 1f(Q) KIINCGr JMI(Q)IB3 JECCIHI(Q) ENGLISH SECTION OF THE SITUATIONIST INTERNATIONAL IF([J)IF ffiIE V ([J) IL lUilII ([J) W §IFIEIEIIJ) IHIII§il([J) ffiY ADDITIONAL RESEARCH BY DEREK HARRIS AND MALCOLM HOPKINS Illustrations: 'The Riots in Moorfields' (cover), 'The London Riots', 'at Langdale's' by 'Phiz' Hablot K. Browne, Horwood's 1792-9 'Plan of London', 'The Great Rock'n'Roll Swindle', 'Oliver Twist Manifesto' by Malcolm McLaren. Vagrants and historical shout outs: Sandra Belgrave, Stewart Home, Mark Jackson, Mark Saunders, Joe D. Stevens at NDTC, Boz & Phiz, J. Paul de Castro, Blue Bredren, Cockney Visionaries, Dempsey, Boss Goodman, Lord George Gordon, Chris Gray, Jonathon Green, Jefferson Hack, Christopher Hibbert, Hoppy, Ian Gilmour, Ish, Dzifa & Simone at The Grape, Barry Jennings, Joe Jones, Shaun Kerr, Layla, Lucas, Malcolm McLaren, John Mead, Simon Morrissey, Don Nicholson-Smith, Michel Prigent (pre-publicity), Charlie Radcliffe, Jamie Reid, George Robertson & Melinda Mash, Dragan Rad, George Rude, Naveen Saleh, Jon Savage, Valerie Solanas, Carolyn Starren & co at Kensington Library, Mark Stewart, Toko, Alex Trocchi, Fred & Judy Vermorel, Warren, Dr. Watson, Viv Westwood, Jack Wilkes, Dave & Stuart Wise Soundtrack: 'It's a London Thing' Scott Garcia, 'Going Mobile' The Who, 'Living for the City' Stevie Wonder, 'Boston Tea Party' Alex Harvey, 'Catholic Day' Adam and the Ants, 'Do the Strand' Roxy Music', 'Rev. -

Non-Explosivity of Stochastically Modeled Reaction Networks

Non-explosivity of stochastically modeled reaction networks that are complex balanced David F. Anderson∗‡ Daniele Cappelletti∗§ Masanori Koyama† Thomas G. Kurtz∗ October 16, 2018 Abstract We consider stochastically modeled reaction networks and prove that if a constant solution to the Kolmogorov forward equation decays fast enough relatively to the tran- sition rates, then the model is non-explosive. In particular, complex balanced reaction networks are non-explosive. 1 Introduction Stochastic reaction networks are mathematical models that describe the time evolution of the counts of interacting objects. Despite their general formulation, these models are pri- marily associated with biochemistry and cell biology, where they are utilized to describe the dynamics of systems of interacting proteins, metabolites, etc.[9, 17, 19, 25]. Other ap- plications include ecology [23], epidemiology [5], and sociology [26, 27, 31]. A more recent development concerns the design of stochastic reaction networks that are able to perform computations [10, 11, 28, 29]. Stochastically modeled reaction networks are typically utilized in biochemistry when at least some of the species in the model have low abundances, perhaps of order 102 or fewer. In this situation, the randomness that arises from the interactions of the molecules cannot arXiv:1708.09356v2 [math.PR] 18 May 2018 be ignored, and the counts of the molecules of the different chemical species are modeled according to a discrete space, continuous-time Markov chain. If more molecules are present, perhaps between order 102 and 103, a diffusion model is often utilized, which describes the system in terms of a stochastic differential equation [4]. When abundances are larger, a deterministic model is often chosen, which describes the dynamics by means of a system of ordinary differential equations [3, 4]. -

Rioting and Time

Rioting and time Collective violence in Manchester, Liverpool and Glasgow, 1800-1939 A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2018 Matteo Tiratelli School of Social Sciences 1 Table of contents Abstract 4 Declaration & Copyright 5 Acknowledgements 6 Chapter 1 — Rioting and time 7 Chapter 2 — Don’t call it a riot 24 Chapter 3 — Finding riots and describing them 42 Chapter 4 — Riots in space, time and society 64 Chapter 5 — The changing practice of rioting 102 Chapter 6 — The career of a riot: triggers and causes 132 Chapter 7 — How do riots sustain themselves? 155 Chapter 8 — Riots: the past and the future 177 Bibliography 187 Appendix 215 Word count: 70,193 2 List of tables Table 1: The spaces where riots started 69 Table 2: The places where riots started 70 Table 3: The number of riots happening during normal working hours 73 Table 4: The number of riots which happen during particular calendrical events 73 Table 5: The proportion of non-industrial riots by day of the week 75 Table 6: The likelihood of a given non-industrial riot being on a certain day of the week 75 Table 7: The likelihood of a given riot outside of Glasgow involving prison rescues 98 Table 8: The likelihood of a given riot involving begging or factory visits 111 Table 9: The likelihood of a given riot targeting specific individuals or people in their homes 119 List of figures Figure 1: Angelus Novus (1920) by Paul Klee 16 Figure 2: Geographic spread of rioting in Liverpool 67 Figure 3: Geographic spread of rioting in Manchester 68 Figure 4: Geographic spread of rioting in Glasgow 68 Figure 5: The number of riots per year 78 Figure 6: The number of riots involving prison rescues per year 98 3 Abstract The 19th century is seen by many as a crucial turning point in the history of protest in Britain and across the global north. -

The History of Riots in London Shows That Persistent Inequality and Injustice Is Always Likely to Breed Periodic Violent Uprisings

blogs.lse.ac.uk http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/2011/10/25/london-riot-history/ The history of riots in London shows that persistent inequality and injustice is always likely to breed periodic violent uprisings. The August 2011 riots in London prompted many commentators to look back on previous riots in the city and the country to see what common threads, if any, run through outbreaks of public disorder. Jerry White examines the Gordon Riots, the Hyde Park riots of 1855 and the Brixton riots of 1981 and finds that perceived inequalities and injustice in London have and will continue to breed periodic violent uprisings. Riot and London. At first sight the words sit uneasily together, for traditionally London is a city known best for its order, civility and tolerance. Yet in a long history there is space for more than one tradition, and from time to time, every generation or so, rioting in London has challenged the forces of order and stretched them past breaking point. At times London has seemed on the brink of civil war. The history of London’s riots reveals great differences between them. What possible similarity can there be between the August riots of 2011 and, say, the uproar attending the election campaigns and imprisonment of John Wilkes in 1768? It seems not much, though both had some features in common (an element of organisation, for instance, and reckless violence against those seeking to quell the disturbances). But perhaps reflecting further on some of these troubled events, while giving just weight to the very specific triggers that led to rioting in the first place, can begin to unpick those structural features of London life that have caused its tradition of riot to endure over time, and make it likely to continue to do so.