Seismology.Html

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insights from the P Wave Travel Time Tomography in the Upper Mantle Beneath the Central Philippines

remote sensing Article Insights from the P Wave Travel Time Tomography in the Upper Mantle Beneath the Central Philippines Huiyan Shi 1 , Tonglin Li 1,*, Rui Sun 2, Gongbo Zhang 3, Rongzhe Zhang 1 and Xinze Kang 1 1 College of Geo-Exploration Science and Technology, Jilin University, No.938 Xi Min Zhu Street, Changchun 130026, China; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (R.Z.); [email protected] (X.K.) 2 CNOOC Research Institute Co., Ltd., Beijing 100028, China; [email protected] 3 State Key Laboratory of Geodesy and Earth’s Dynamics, Innovation Academy for Precision Measurement Science and Technology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430071, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: In this paper, we present a high resolution 3-D tomographic model of the upper mantle obtained from a large number of teleseismic travel time data from the ISC in the central Philippines. There are 2921 teleseismic events and 32,224 useful relative travel time residuals picked to compute the velocity structure in the upper mantle, which was recorded by 87 receivers and satisfied the requirements of teleseismic tomography. Crustal correction was conducted to these data before inversion. The fast-marching method (FMM) and a subspace method were adopted in the forward step and inversion step, respectively. The present tomographic model clearly images steeply subduct- ing high velocity anomalies along the Manila trench in the South China Sea (SCS), which reveals a gradual changing of the subduction angle and a gradual shallowing of the subduction depth from the north to the south. -

The East African Rift System in the Light of KRISP 90

ELSEVIER Tectonophysics 236 (1994) 465-483 The East African rift system in the light of KRISP 90 G.R. Keller a, C. Prodehl b, J. Mechie b,l, K. Fuchs b, M.A. Khan ‘, P.K.H. Maguire ‘, W.D. Mooney d, U. Achauer e, P.M. Davis f, R.P. Meyer g, L.W. Braile h, 1.0. Nyambok i, G.A. Thompson J a Department of Geological Sciences, University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, TX 79968-0555, USA b Geophysikalisches Institut, Universitdt Karlwuhe, Hertzstrasse 16, D-76187Karlsruhe, Germany ’ Department of Geology, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LEl 7RH, UK d U.S. Geological Survey, Office of Earthquake Research, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA ’ Institut de Physique du Globe, Universite’ de Strasbourg, 5 Rue Ret& Descartes, F-67084 Strasbourg, France ‘Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of California at Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90024, USA ’ Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wuconsin at Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA h Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA i Department of Geology, University of Nairobi, P.O. Box 14576, Nairobi, Kenya ’ Department of Geophysics, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA Received 21 September 1992; accepted 8 November 1993 Abstract On the basis of a test experiment in 1985 (KRISP 85) an integrated seismic-refraction/ teleseismic survey (KRISP 90) was undertaken to study the deep structure beneath the Kenya rift down to depths of NO-150 km. This paper summarizes the highlights of KRISP 90 as reported in this volume and discusses their broad implications as well as the structure of the Kenya rift in the general framework of other continental rifts. -

Summary of the New W4300 Course in DEES: “The Earth's Deep Interior” Instructor: Paul G

Summary of the new W4300 course in DEES: “The Earth's Deep Interior” Instructor: Paul G. Richards ([email protected]) This course emphasizes the geophysical study of Earth structure below the crust, drawing upon geodesy, geomagnetism, gravity, thermal studies, seismology, and some geochemistry. It covers the principal techniques by which discoveries have been made in deep Earth structure, and describes particular features of the mantle, and fluid and solid cores, such as: • the upper mantle beneath old and young oceans and continents • the transition zone in the mantle between about 400 and 700 km depth (within which density and elastic moduli increase anomalously with depth), • the lowermost mantle and core/mantle boundary (across which density doubles and sound speed halves), and • the outer core/inner core boundary (discovered by seismology, and profoundly affecting the Earth's magnetic field). The course is part of the core curriculum for graduate students in solid Earth geophysics and marine geophysics, is an elective for solid Earth geochemistry and geology, and is accessible to undergraduate science majors with adequate math and physics. The course, together with EESC W 4950x (Math Methods in the Earth Sciences), replaces the previous W 4945x – 4946y (Geophysical Theory I and II). It includes parts of previous courses (no longer listed) in seismology, geomagnetism, and thermal history. Emphasis is on current structure, rather than evaluation of dynamic processes (such as convection). Prerequisites calculus, differential -

Seismic Wavefield Imaging of Earth's Interior Across Scales

TECHNICAL REVIEWS Seismic wavefield imaging of Earth’s interior across scales Jeroen Tromp Abstract | Seismic full- waveform inversion (FWI) for imaging Earth’s interior was introduced in the late 1970s. Its ultimate goal is to use all of the information in a seismogram to understand the structure and dynamics of Earth, such as hydrocarbon reservoirs, the nature of hotspots and the forces behind plate motions and earthquakes. Thanks to developments in high- performance computing and advances in modern numerical methods in the past 10 years, 3D FWI has become feasible for a wide range of applications and is currently used across nine orders of magnitude in frequency and wavelength. A typical FWI workflow includes selecting seismic sources and a starting model, conducting forward simulations, calculating and evaluating the misfit, and optimizing the simulated model until the observed and modelled seismograms converge on a single model. This method has revealed Pleistocene ice scrapes beneath a gas cloud in the Valhall oil field, overthrusted Iberian crust in the western Pyrenees mountains, deep slabs in subduction zones throughout the world and the shape of the African superplume. The increased use of multi- parameter inversions, improved computational and algorithmic efficiency , and the inclusion of Bayesian statistics in the optimization process all stand to substantially improve FWI, overcoming current computational or data- quality constraints. In this Technical Review, FWI methods and applications in controlled- source and earthquake seismology are discussed, followed by a perspective on the future of FWI, which will ultimately result in increased insight into the physics and chemistry of Earth’s interior. -

Full-Text PDF (Final Published Version)

Pritchard, M. E., de Silva, S. L., Michelfelder, G., Zandt, G., McNutt, S. R., Gottsmann, J., West, M. E., Blundy, J., Christensen, D. H., Finnegan, N. J., Minaya, E., Sparks, R. S. J., Sunagua, M., Unsworth, M. J., Alvizuri, C., Comeau, M. J., del Potro, R., Díaz, D., Diez, M., ... Ward, K. M. (2018). Synthesis: PLUTONS: Investigating the relationship between pluton growth and volcanism in the Central Andes. Geosphere, 14(3), 954-982. https://doi.org/10.1130/GES01578.1 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY-NC Link to published version (if available): 10.1130/GES01578.1 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via Geo Science World at https://doi.org/10.1130/GES01578.1 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Research Paper THEMED ISSUE: PLUTONS: Investigating the Relationship between Pluton Growth and Volcanism in the Central Andes GEOSPHERE Synthesis: PLUTONS: Investigating the relationship between pluton growth and volcanism in the Central Andes GEOSPHERE; v. 14, no. 3 M.E. Pritchard1,2, S.L. de Silva3, G. Michelfelder4, G. Zandt5, S.R. McNutt6, J. Gottsmann2, M.E. West7, J. Blundy2, D.H. -

Geophysical Journal International

Geophysical Journal International Geophys. J. Int. (2017) 209, 1892–1905 doi: 10.1093/gji/ggx133 Advance Access publication 2017 April 1 GJI Seismology Surface wave imaging of the weakly extended Malawi Rift from ambient-noise and teleseismic Rayleigh waves from onshore and lake-bottom seismometers N.J. Accardo,1 J.B. Gaherty,1 D.J. Shillington,1 C.J. Ebinger,2 A.A. Nyblade,3 G.J. Mbogoni,4 P.R.N. Chindandali,5 R.W. Ferdinand,6 G.D. Mulibo,6 G. Kamihanda,4 D. Keir,7,8 C. Scholz,9 K. Selway,10 J.P. O’Donnell,11 G. Tepp,12 R. Gallacher,7 K. Mtelela,6 J. Salima5 and A. Mruma4 1Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, NY 10964, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70118,USA 3Department of Geosciences, The Pennsylvania State University, State College, PA 16802,USA 4Geological Survey of Tanzania, Dodoma, Tanzania 5Geological Survey Department of Malawi, Zomba, Malawi 6Department of Geology, University of Dar es Salaam, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania 7National Oceanography Centre Southampton, University of Southampton, Southampton S017 1BJ, United Kingdom 8Dipartimento di Scienzedella Terra, Universita degli Studi di Firenze, Florence 50121,Italy 9Department of Earth Sciences, Syracuse University, New York, NY 13210,USA 10Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Macquarie University, NSW 2109, Australia 11School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS29JT, United Kingdom 12Alaska Volcano Observatory, U.S. Geological Survey, Anchorage, AK 99775,USA Accepted 2017 March 28. Received 2017 March 13; in original form 2016 October 12 SUMMARY Located at the southernmost sector of the Western Branch of the East African Rift System, the Malawi Rift exemplifies an active, magma-poor, weakly extended continental rift. -

Seismic Tomography Shows That Upwelling Beneath Iceland Is Confined to the Upper Mantle

Geophys. J. Int. (2001) 146, 504–530 Seismic tomography shows that upwelling beneath Iceland is confined to the upper mantle G. R. Foulger,1 M. J. Pritchard,1 B. R. Julian,2 J. R. Evans,2 R. M. Allen,3 G. Nolet,3 W. J. Morgan,3 B. H. Bergsson,4 P. Erlendsson,4 S. Jakobsdottir,4 S. Ragnarsson,4 R. Stefansson4 and K. Vogfjo¨rd5 1 Department of Geological Sciences, University of Durham, Durham, DH1 3LE, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 2 US Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Road., Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA 3 Department of Geological and Geophysical Sciences, Guyot Hall, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544–5807, USA 4 Meteorological Office of Iceland, Bustadavegi 9, Reykjavik, Iceland 5 National Energy Authority, Grensasvegi 9, Reykjavik, Iceland Accepted 2001 April 3. Received 2001 March 19; in original form 2000 August 1 SUMMARY We report the results of the highest-resolution teleseismic tomography study yet performed of the upper mantle beneath Iceland. The experiment used data gathered by the Iceland Hotspot Project, which operated a 35-station network of continuously recording, digital, broad-band seismometers over all of Iceland 1996–1998. The structure of the upper mantle was determined using the ACH damped least-squares method and involved 42 stations, 3159 P-wave, and 1338 S-wave arrival times, including the phases P, pP, sP, PP, SP, PcP, PKIKP, pPKIKP, S, sS, SS, SKS and Sdiff. Artefacts, both perceptual and parametric, were minimized by well-tested smoothing techniques involving layer thinning and offset-and-averaging. Resolution is good beneath most of Iceland from y60 km depth to a maximum of y450 km depth and beneath the Tjornes Fracture Zone and near-shore parts of the Reykjanes ridge. -

Chapter 2 the Evolution of Seismic Monitoring Systems at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory

Characteristics of Hawaiian Volcanoes Editors: Michael P. Poland, Taeko Jane Takahashi, and Claire M. Landowski U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1801, 2014 Chapter 2 The Evolution of Seismic Monitoring Systems at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory By Paul G. Okubo1, Jennifer S. Nakata1, and Robert Y. Koyanagi1 Abstract the Island of Hawai‘i. Over the past century, thousands of sci- entific reports and articles have been published in connection In the century since the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory with Hawaiian volcanism, and an extensive bibliography has (HVO) put its first seismographs into operation at the edge of accumulated, including numerous discussions of the history of Kīlauea Volcano’s summit caldera, seismic monitoring at HVO HVO and its seismic monitoring operations, as well as research (now administered by the U.S. Geological Survey [USGS]) has results. From among these references, we point to Klein and evolved considerably. The HVO seismic network extends across Koyanagi (1980), Apple (1987), Eaton (1996), and Klein and the entire Island of Hawai‘i and is complemented by stations Wright (2000) for details of the early growth of HVO’s seismic installed and operated by monitoring partners in both the USGS network. In particular, the work of Klein and Wright stands and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The out because their compilation uses newspaper accounts and seismic data stream that is available to HVO for its monitoring other reports of the effects of historical earthquakes to extend of volcanic and seismic activity in Hawai‘i, therefore, is built Hawai‘i’s detailed seismic history to nearly a century before from hundreds of data channels from a diverse collection of instrumental monitoring began at HVO. -

Gji-Keyword-List-Updated2016.Pdf

COMPOSITION and PHYSICAL PROPERTIES Composition and structure of the continental crust Composition and structure of the core Composition and structure of the mantle Composition and structure of the oceanic crust Composition of the planets Creep and deformation Defects Elasticity and anelasticity Electrical properties Equations of state Fault zone rheology Fracture and flow Friction High-pressure behaviour Magnetic properties Microstructure Permeability and porosity Phase transitions Plasticity, diffusion, and creep GENERAL SUBJECTS Core Gas and hydrate systems Geomechanics Geomorphology Glaciology Heat flow Hydrogeophysics Hydrology Hydrothermal systems Instrumental noise Ionosphere/atmosphere interactions Ionosphere/magnetosphere interactions Mantle processes Ocean drilling Structure of the Earth Thermochronology Tsunamis Ultra-high pressure metamorphism Ultra-high temperature metamorphism GEODESY and GRAVITY Acoustic-gravity waves Earth rotation variations Geodetic instrumentation Geopotential theory Global change from geodesy Gravity anomalies and Earth structure Loading of the Earth Lunar and planetary geodesy and gravity Plate motions Radar interferometry Reference systems Satellite geodesy Satellite gravity Sea level change Seismic cycle Space geodetic surveys Tides and planetary waves Time variable gravity Transient deformation GEOGRAPHIC LOCATION Africa Antarctica Arctic region Asia Atlantic Ocean Australia Europe Indian Ocean Japan New Zealand North America Pacific Ocean South America GEOMAGNETISM and ELECTROMAGNETISM Archaeomagnetism -

Crustal Structure of the Eastern Anatolia Region (Turkey) Based on Seismic Tomography

geosciences Article Crustal Structure of the Eastern Anatolia Region (Turkey) Based on Seismic Tomography Irina Medved 1,2,* , Gulten Polat 3 and Ivan Koulakov 1 1 Trofimuk Institute of Petroleum Geology and Geophysics SB RAS, Prospekt Koptyuga, 3, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia; [email protected] 2 Sobolev Institute of Geology and Mineralogy SB RAS, Prospekt Koptyuga, 3, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia 3 Department of Civil Engineering, Yeditepe University, 26 Agustos Yerleskesi, 34755 Istanbul, Turkey; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-952-922-49-67 Abstract: Here, we investigated the crustal structure beneath eastern Anatolia, an area of high seismicity and critical significance for earthquake hazards in Turkey. The study was based on the local tomography method using data from earthquakes that occurred in the study area provided by the Turkiye Cumhuriyeti Ministry of Interior Disaster and Emergency Management Directorate Earthquake Department Directorate of Turkey. The dataset used for tomography included the travel times of 54,713 P-waves and 38,863 S-waves from 6355 seismic events. The distributions of the resulting seismic velocities (Vp, Vs) down to a depth of 60 km demonstrate significant anomalies associated with the major geologic and tectonic features of the region. The Arabian plate was revealed as a high-velocity anomaly, and the low-velocity patterns north of the Bitlis suture are mostly associated with eastern Anatolia. The upper crust of eastern Anatolia was associated with a ~10 km thick high-velocity anomaly; the lower crust is revealed as a wedge-shaped low-velocity anomaly. This kind of seismic structure under eastern Anatolia corresponded to the hypothesized existence of Citation: Medved, I.; Polat, G.; a lithospheric window beneath this collision zone, through which hot material of the asthenosphere Koulakov, I. -

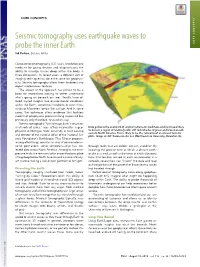

Seismic Tomography Uses Earthquake Waves to Probe the Inner Earth CORE CONCEPTS Sid Perkins, Science Writer

CORE CONCEPTS Seismic tomography uses earthquake waves to probe the inner Earth CORE CONCEPTS Sid Perkins, Science Writer Computerized tomography (CT) scans revolutionized medicine by giving doctors and diagnosticians the ability to visualize tissues deep within the body in three dimensions. In recent years, a different sort of imaging technique has done the same for geophysi- cists. Seismic tomography allows them to detect and depict subterranean features. The advent of the approach has proven to be a boon for researchers looking to better understand what’s going on beneath our feet. Results have of- fered myriad insights into environmental conditions within the Earth, sometimes hundreds or even thou- sands of kilometers below the surface. And in some cases, the technique offers evidence that bolsters models of geophysical processes long suspected but previously only theorized, researchers say. Seismic tomography “lets us image Earth’s structures at all sorts of scales,” says Jeffrey Freymueller, a geo- Data gathered by a network of seismic instruments (red) have enabled researchers physicist at Michigan State University in East Lansing to discern a region of relatively cold, stiff rock (shades of green and blue) beneath eastern North America. This is likely to be the remnants of an ancient tectonic and director of the national office of the National Sci- plate. Image credit: Suzan van der Lee (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL). ence Foundation’s EarthScope. That 15-year program, among other things, operates an array of seismometers— some permanent, some temporary—that has col- through rocks that are colder, denser, and drier. By lected data across North America. -

PEAT8002 - SEISMOLOGY Lecture 13: Earthquake Magnitudes and Moment

PEAT8002 - SEISMOLOGY Lecture 13: Earthquake magnitudes and moment Nick Rawlinson Research School of Earth Sciences Australian National University Earthquake magnitudes and moment Introduction In the last two lectures, the effects of the source rupture process on the pattern of radiated seismic energy was discussed. However, even before earthquake mechanisms were studied, the priority of seismologists, after locating an earthquake, was to quantify their size, both for scientific purposes and hazard assessment. The first measure introduced was the magnitude, which is based on the amplitude of the emanating waves recorded on a seismogram. The idea is that the wave amplitude reflects the earthquake size once the amplitudes are corrected for the decrease with distance due to geometric spreading and attenuation. Earthquake magnitudes and moment Introduction Magnitude scales thus have the general form: A M = log + F(h, ∆) + C T where A is the amplitude of the signal, T is its dominant period, F is a correction for the variation of amplitude with the earthquake’s depth h and angular distance ∆ from the seismometer, and C is a regional scaling factor. Magnitude scales are logarithmic, so an increase in one unit e.g. from 5 to 6, indicates a ten-fold increase in seismic wave amplitude. Note that since a log10 scale is used, magnitudes can be negative for very small displacements. For example, a magnitude -1 earthquake might correspond to a hammer blow. Earthquake magnitudes and moment Richter magnitude The concept of earthquake magnitude was introduced by Charles Richter in 1935 for southern California earthquakes. He originally defined earthquake magnitude as the logarithm (to the base 10) of maximum amplitude measured in microns on the record of a standard torsion seismograph with a pendulum period of 0.8 s, magnification of 2800, and damping factor 0.8, located at a distance of 100 km from the epicenter.