Pdf 970.03 K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf 540.27 K

International Journal of Finance and Managerial Accounting, Vol.1, No.4, Winter 2016 Is Hesaabdaaree an Adequate Equivalent for Accounting? Ahmad Nasseri Assistant Professor of Accounting, University of Sistan and Baluchestan, Zahedan, Iran (Corresponding Author) [email protected] Hassan Yazdifar Mohammad Ali Mahmoodi Akram Arefi Professor of Accounting, Salford Associate Professor of Persian M.A.in Persian Language and University, UK Language and Linguistics, Linguistics, University of Sistan and University of Sistan and Baluchestan, Zahedan, Iran Baluchestan, Zahedan, Iran ABSTRACT Some of the difficulties and misunderstandings that happen in accounting theory, practice, regulation and education are grounded in language and linguistics. As an illustration of this the Persian equivalent of 'accounting' is linguistically analysed to reveal how a mistranslation may cause difficulties in understanding and improving Iranian Accounting. This paper shows how Hesaabdaaree is not a complete Persian equivalent for 'Accounting'. The examination is followed through two linguistic methods. First, a localistic lexical semantic approach is applied. Hesaabdaaree is a combination of an Arabic noun and a Persian suffix. It is then argued that the impuissance and limitations of hesaabdaaree in transferring all conceptual aspects of accounting has not arisen from hesaab, but daaree. Next, a holistic lexical semantic approach is applied to examine the sense of Hesaabdaaree within its word family to find out if it conveys the precise sense of accounting. Both the localistic and holistic examinations reveal the weaknesses of the Persian word Hesaabdaaree in transferring the exact meaning of 'Accounting'. This paper adds to the existing body of accounting theory and methodology by: a) introducing and examining a linguistic problem (i.e. -

Art Illustration of Khaghani and Sanai with Beloved Figure

Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Art Illustration of Khaghani and Sanai with Beloved Figure Fazel Abbas Zadeh, Parisa Alizadeh1 1.Department of Persian Language and Literature, Parsabad Moghan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Parsabad Moghan, Iran Abstract In this paper, a beloved figure in the poetry of Khaghani and Sanai and art illustration of the beloved poet both studied and analyzed. Both Sanai with entering his poetic mysticism, poetry and pomp Khaghani a special place in Persian poetry and the tradition of its time focused on the issue of love and beloved. However, this possibility is the mystical dimension or later Ghanaian or other dimensions. The themes are discussed in this article, from the perspective of artistic imagery and imagery in describing the beloved and important way overnight. For each poetic images and titles to mention a poem by each poet control is sufficient. Finally, the author focuses on the overall analysis and the desired result is achieved. Keywords: beloved, Khaghani, Sanai, poetry, lyrics, imagery. http://www.ijhcs.com/index.php/ijhcs/index Page 2146 Special Issue INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Introduction: In Persian poetry lover and beloved literary tradition is one of the themes in literature, especially in Ghana and its lyric, there has been much attention and centuries, in every period of Persian poetry, there have been two specific attitudes towards it. In fact, the beloved main role is decisive and in other words, the circuit is of Iranian literature. Art imaging, the main focus centered and superficial beauty of the beloved, the imaginary form of the simile, metaphor, virtual instruments and diagnostics (animation); that is the beauty and wonders of nature poet pays to describe the beloved around. -

Year 2018-19

Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi List of Students Department Wise/State Wise/Gender Wise For Session Jul/2018 - Dec/2018,Jul/2018 - Jun/2019 AND Jan/2018 - Dec/2018 Run Date : 12/02/2020 Department :ALL Admission Type : ALL S.No. State/Country Gender S.No. Student ID Name Category Course 1 Andhra Pradesh Female 1 20175620 Gulafsha Fatima Muslim Women M.A./M.Sc. Mathematics( Self Finance) - II Yr. 2 20173501 Afreen Sheikh Muslim M.A.(Mass Communication)(Semester) - III Sem. 3 20185044 Aseya Fatima Muslim Women B.Tech.(Computer Engineering)(Semester) - I Sem. 4 20172098 Intifada P.B. Muslim Women M.A.(Convergent Journalism)(Semester Self Finance) - III Sem. Male 5 20182188 Qureshi Asif Ali Muslim OBC/Muslim ST M.A.(History)(Semester) - I Sem. 6 20182861 Ismail Shaik Arifulla Muslim B.A. (H) Arabic(Semester) - I Sem. 7 20181456 Mohammed Feroz Muslim M.A.(Conflict Analysis & Peace Building)(Semester) - I Sem. 8 20177481 Shaik Mohammed Muslim OBC/Muslim ST B.Tech.(Mechanical Muaviya Engineering)(Semester) - III Sem. 9 20181401 Abdul Khadar Muslim B.Ed. - I Yr. 10 20186322 Saidheeraj General M.A.(Economics)(Semester) - I Vayugundlachenchu Sem. 11 20157693 Mohammed Omar NRI ward under B.Tech.(Electrical Siddiqui Supernumeray category Engineering)(Semester) - VII Sem. 12 20159109 Venkata Saibabu General Ph.D.(Bio Science)(Semester) Thokala 13 20172111 Bhanu Prasad Palanati General M.Ed.(Special Education)(Semester) - III Sem. 14 20174688 Fakruddin Mohammed Muslim M.A.(Islamic Studies)(Semester) Ali Halaharvi - III Sem. 15 20177060 Abdul Sofiyan Muslim M.A.(Political Science)(Semester) - III Sem. 16 20148252 C. -

Scientific-Executive Identity Card

Scientific-executive identity card Rank: Associate Professor 16 Ending place: Payame Noor University; Center of Tehran Organizational position: Definitive official faculty member Scientific and research records: -PhD in Persian Language and Literature from the University of Tehran, 2005 -Thesis title: The morphology of the social system in Ferdowsi Shahnameh Master of Persian Language and Literature from the University of Tehran, 1998 Thesis title: Description and review of ten poems by Khaghani Bachelor of Persian Language and Literature from Kashan University (1995) (Excellent scientific rank) _______________________________________________________________________ Scientific and research activities: Books 1- Payamani, Behnaz, The morphology of Ferdowsi's Shahnameh: "The structure of the social system based on socio-cultural themes" Zavar Publications, 2013 2- Payamani, Behnaz, correction, exclusion and suspension of the manuscript of "Majmareh; Treatise on Perfume" by Mohammad Karim Ibn Ibrahim Kermani, Alam Publishing, 2014 3- Payamani, Behnaz, Effat Naderinejad, A Journey in the Garden of Antishe Ghazali (Religious Attitude of the Alchemy of Happiness to the Transcendence of Body and Soul) 4- Karbala in the Ottoman Archive by Dilek Qaya, (translation), in progress Articles: 1- Payamani, Behnaz, A Study of Economic Developments and the Rate of Industrial Growth in Ferdowsi Shahnameh, Faculty Journal Literature and Humanities of Tarbiat Moallem University of Tehran, Year 16, Issue 60, Spring 2008 (Scientific- Research) 2- Payamani, Behnaz, A Study of the Doctrine and Mourning Rite Based on Folk Beliefs in Ferdowsi Shahnameh, Journal of the Faculty of Literature, University of Tehran, 2008, No. 187 (Scientific-Research) 3- Payamani, Behnaz, style and content review of the manuscript of the exhibition; Thesis in Perfume, Journal of Literature and Language of Kerman, Fall 18 and Winter 2015 (Scientific-Research) 4- Payamani, Behnaz, The position of professions in Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, Quarterly Journal of Stylistics of Order and Prose, Fall 2008 No. -

The Effect of Tolerance on Balancing Social Relations in Terms of Molana’S Point of View in Masnawi

Journal of History Culture and Art Research (ISSN: 2147-0626) Tarih Kültür ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi Vol. 6, No. 3, June 2017 Revue des Recherches en Histoire Culture et Art Copyright © Karabuk University http://kutaksam.karabuk.edu.tr مجلة البحوث التاريخية والثقافية والفنية DOI: 10.7596/taksad.v6i3.986 Citation: Kalesara, G., & Mashoor, P. (2017). The Effect of Tolerance on Balancing Social Relations in Terms of Molana’s Point of View in Masnawi. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 6(3), 1158-1175. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v6i3.986 The Effect of Tolerance on Balancing Social Relations in Terms of Molana’s Point of View in Masnawi Ghasem Yaghubinezhad Kalesara*1, Parvindokht Mashoor2 Abstract Fresh perceptions and variations in concepts introduced by Molana are among the beautiful effects of Masnavi. It is full of various ploys and mystical paraphrases which imply a new meaning in social issues. In this paper, after a short study of tolerance and its background in Islamic culture and western civilization, it has been discussed socially in Molana’s period. The researchers try to explain tolerance on the basis of two standpoints, by believing that it has a deep influence on balancing human relations. Firstly, we want to know if it is a heavenly or a secular issue since our mystical works talk about an inner source while modern thought is focused on the scientific and experiential roots of wisdom. But in the second step we investigate the relationship between the tolerance and its benefit for the human social rights. Although Molana’s attitude in most of Masnavi’s poems relies on the traditional points of view, this study has realized his mind clarity and vigilance and has come to valuable deductions. -

Conceptual Comparison of Self-Esteem in Western Psychology

ijcrb.webs.com FEBRUARY 2013 INTERDISCIPLINARY JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH IN BUSINESS VOL 4, NO 10 Conceptual Comparison of Self-esteem in Western Psychology and Islam Religion Abolfath Azizi Abarghooi2 Maryam Azizi Abarghooi3 Abstract Self-esteem is one of the concepts that western psychologists have studied to describe, explain and develop it and they have presented different theories and approaches about this concept. On the other hand, this issue is one of the important concepts of Islamic ethics behind there are a great deal of Quran verses and innocent stories. There is no doubt that investigation and interdisciplinary comparison of self-esteem would have a great portion to develop knowledge. In this regard, we will try to define self-esteem based on the western psychologists, primarily, and then, with utilizing the related verses of Quran, we will compare and criticize that one with Islamic self-esteem. The analysis of these definitions shows that as psychology considers self-esteem to be as a science, it is individualist and based on individual criteria. But Islamic definition of self-esteem is based on monotheism and divine values and Islamic self-esteem area includes both mundane life and hereafter life. Therefore, Islamic definition of self-esteem is more comprehensive. Keywords: SELF-ESTEEM, PSYCHOLOGY, ISLAM, QURAN Introduction Nowadays, the discussion of self-esteem is a prominent topic in the science of psychology. Discussion of self-esteem began from the works of a psychoanalyst named Carl Rogers (1961). Rogers believed that a person’s low amount of self-esteem has chronic deduction effects in academic achievement, depression, and unemployment (Biabangard, 2007, p. -

James Turrell Awarded the National Medal of Arts

153 SEP- OCT 2014 Vol. XXIV No. 153 A Thousand Years of the Persian Book Remembering Simin Behbahani Volleyball Diplomacy Enlightening: James Turrell Awarded the ISSD Registration National Medal of Arts 2014-2015 Branch I, Sunday, September 7 Branch II, Thursday, September 11 • We Are Way Pasts the Wake-Up Call ... • Where did all the good people go? • Getting Started With the School Year • Back-to-School Anxiety Photo Essay • How Much Alcohol is Too Much? Salaamaat from Jalazone No. 153/ September - October 2014 1 153 Since 1991 By: Shahri Estakhry Persian Cultural Center’s We Are Way Pasts the Wake-Up Call ... Bilingual Magazine Is a bi - monthly publication organized for literary, cultural and information purposes We must accept the fact that so long as hunger, illiteracy, and poverty exist in the world, even Financial support is provided by the City of hoping for peace is in a distance far away. According to the United Nations, every 25 seconds San Diego Commission for Arts and Culture. a child dies of hunger. According to UNESCO, over 26 percent of the world’s adult population is illiterate, and around 93 percent of the people of the world do not have a roof over their head. Persian Cultural Center Conversely, according to Forbes magazine (March 3, 2014), this past year a record-breaking 6790 Top Gun St. #7, San Diego, CA 92121 Tel (858) 552-9355 number of billionaires made the list of the world’s richest people, with an “aggregate net worth Fax & Message: (619) 374-7335 of $6.4 trillion.” The contrast is so devastating it boggles the mind! Email: [email protected] Web site: www.pccus.org www.pccsd.org To have a million dollars is nothing extraordinary, at least not in California. -

CABA-MDTP REG LIST JULY-2017.Xlsx

1 Candiates Registered in CABA-MDTP JULY-2017 Session centre_code registration_no Candidate Particulars 110006 1707110006001 RUBEENA BEGUM D/o MOHD SHABBIR AHMED 110006 1707110006002 SYEDA ASRA AMTUL KHATIJA D/o SYED HABEEBULLAH KHADRI 110006 1707110006003 AMREEN FATIMA D/o MOHAMMED CHAND PASHA 110006 1707110006004 NAZIA BEGUM D/o MOHD ISMAIL 110006 1707110006005 NIKHAT SULTANA D/o MOHD KHAJA 110006 1707110006006 ASMA BEGUM D/o MOHD IQBAL 110006 1707110006007 SHAHEDA BEGUM D/o MOHD IQBAL 110006 1707110006008 AFREEN BEGUM D/o MOHD GHOOSE 110006 1707110006009 ADIBA FATIMA D/o MOHD ABDUL SAMEE 110006 1707110006010 YAMEEN FANTESAR D/o SYED AMEER ULLAH HUSSAINI 110006 1707110006011 AZIZA BEGUM D/o MIRZA LIYAQATHULLAH BAIG 110006 1707110006012 MOHAMMED SULTAN MOHIUDDIN S/o MOHAMMED KHALEEL AHMED 110006 1707110006013 MOHD SAMAD S/o YAKUB ALI 110006 1707110006014 MOHD ABDUL MUQTADIR S/o MOHD ABDUL SAMEE 110006 1707110006015 MUMTAZ AHMED SIDDIQUE S/o MINHAJUDDIN 110006 1707110006016 MOHAMMAD ABDUL BATIN S/o MOHAMMAD ABDUL RASHEED 110006 1707110006017 MD RAHEEM S/o MD RUSTUM 110006 1707110006018 MOHAMMED HAMEEDUDDIN S/o MOHAMMED RIYAZUDDIN 110006 1707110006019 SYED SAMI S/o SYED NISAR 110006 1707110006020 ABDUL RAHMAN S/o SARFARAZ AHMED 110006 1707110006021 SYED OSMAN QADRI S/o SYED KHADAR QADRI 110006 1707110006022 MOHD IRBAZ ZAKARIA S/o MOHD YAQOOB KALEEM 110006 1707110006023 MOHD SHOEB S/o MOHD FAROOQ 110006 1707110006024 MUHAMMAD KAMRAN AZEEZ S/o MUHAMMAD AZEEZ AKHTAR 110006 1707110006025 ABDUL MAJEED S/o ABDUL SATTAR 110006 1707110006026 SHAIK -

Advances in Environmental Biology, 8(13) August 2014, Pages: 1541-1549

Advances in Environmental Biology, 8(13) August 2014, Pages: 1541-1549 AENSI Journals Advances in Environmental Biology ISSN-1995-0756 EISSN-1998-1066 Journal home page: http://www.aensiweb.com/AEB/ A View on Hafez Saad Tabrizi Based on Mjlis Library Manuscript 1Dr. Ahmed Hasani Ranjbar and 2Nazanin Rajabi Seighari 1Professor of Islamic Azad University, Central Tehran branch, Tehran, Iran 2Ph.D. Student at Persian language and literature, Islamic Azad University, Central Tehran branch, Tehran, Iran ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Treasures of Persian Language and Literature manuscripts are kept in the great libraries Received 25 September 2014 of Iran and the world. But the real value of their treasures appears when taken out from Received in revised form the hidden corners, trimmed and used by interested scholars and literature elites. 8 November 2014 Persian Manuscripts are about the customs and culture of Iran, so it is on the shoulder Accepted 14 November 2014 of researchers to correct them and make them available for everyone. Hafez Saad Available online 23 November 2014 Tabrizi poetry manuscript is one of the treasures of Persian literature. The author of this article has attempted to correct this ninetieth century poetry poems. This paper includes Keywords: a brief introduction of the poet, a glimpse of the poet manuscript and correction features Manuscripts, Persian poetry, ninetieth are explained, as well. century poetry, an obscure poet, Hafez Saad Tabrizi © 2014 AENSI Publisher All rights reserved. To Cite This Article: Ahmed Hasani Ranjbar and Nazanin Rajabi Seighari., A View on Hafez Saad Tabrizi Based on Mjlis Library Manuscript. -

Draft 3 Interview Result Copy

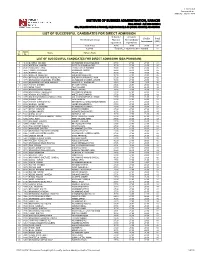

Final Result Announced on : Saturday, July 18, 2020 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI FINAL RESULT ‐ Fall 2020 ROUND 2 BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION O-Level / A-Level / Profile Total Shortlisting Criteria Matric / Intermediate/ Assessment (ALL) Equivalent Equivalent Total Points 30.00 30.00 30.00 90 Cut-Off "Total (ALL)" column has been rounded 81 S. Appl. Name Father's Name No. No. LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) 1 4613 BUSHRA MAJEED MUHAMMAD KHALID MAJEED 27.00 27.00 27.00 81 2 4618 AREESHA HAIDER SYED ZULFIQAR HAIDER 30.00 27.00 28.00 85 3 4630 HAMID BIN TARIQ TARIQ ATA UR REHMAN 30.00 27.00 28.00 85 4 4662 HAMZA MAHMOOD MAHMOOD ANWAR 28.04 26.43 28.00 82 5 4676 RABAHA GUL PASHA GUL 30.00 27.00 29.00 86 6 4685 RAMEEN SHAHZAD KHURRAM SHAHZAD 30.00 27.00 28.00 85 7 4763 MAHNOOR KHURRAM ABDULLAH SHEIKH KHURRAM REHMAN 27.00 27.00 28.00 82 8 4779 MUHAMMAD MUZAMMIL SHAKEEL MUHAMMAD SHAKEEL AHMED 30.00 27.00 29.00 86 9 4808 MUHAMMAD HUZAIFA MAJEED NAWEED UL HAQ MAJID 28.50 27.60 29.00 85 10 4843 FATIMA ZAHEER ZAHEER AHMAD 28.96 26.83 28.00 84 11 4872 AENA TAHIR TAHIR AHMED 27.00 27.00 28.00 82 12 4873 EEMAN SAMAD ZINDANI ABDUL SAMAD 27.00 27.00 28.00 82 13 4894 MUHAMMAD ABDULLAH MUHAMMAD MUSLIM 27.00 27.00 28.00 82 14 4906 AROMA KHURSHEED ANEES QADIR MANGI 27.00 27.00 28.00 82 15 4978 MALIK MUHAMMAD AZAM ALI KHAN MALIK GHAZANFAR ALI KHAN 27.00 27.00 28.00 82 16 5004 NABIHA AZIZ AZIZ REHMAN 27.00 -

Ideal Government from the Viewpoint of Authors And

L Z Y B48 L B4I- L Z S\V Y SU^ ] S\VS E 2= :B [E% C= ! " $# ∗∗∗∗∗∗ -∗∗∗ : : . ! 0/ / # +- . +, ( ) * ' # # $ % & : : /8 9 & . 7 )1 $234 * & 56 # 0)+ 7 )6 D - C)' 7B> 2 )A 2 > ? @ ;< )7= > H7= I6 @FJ K 0E6 ! # 7 EF 0G) 9 . > > 27= 7= # )1 B-. B7= > ) > ! 7L . . > )1 $ M = 7=)1 . ! 6 F $0 ∗∗∗ [email protected] ! NO P= #! AL = # 7= ∗∗∗∗∗∗ [email protected] ! NO P= #! AL = # 7Q )OL VW VW SW/ RU/ X M D- VW RS/U/ C)< D- / S\VS E 2= :B B4I- L Z S_W ` &Z O 27H - [E% . )7 6)- 7H& 9 AB - > 7 )A% 0)+ > ) 7 - 2 7 1 ! 0)+ eP1 $ > bd= c )1 G # > b 0 a! # 9 $& ) 8 0 > 2 71 $a L &# @ ;< 0 B> 7 E & 0F8 )7 # > 0= ) M& f # g! 0= .E 0= $# # > ! 0)+ / )- 9 c h i7= . . A . = ) I = I6 +H7 : . 0F8 C! 0)+ ! : : 7+ 9 6)- . 0= 6)- EF j- )B J8 FI- :» 2 ) N47i )7 & 7=! )7= & *41 # + &# & 7 7 )! $ # & [! E6 @FJ &# C8 [ - 7A * P1 2L% C 0BL 0G SS(. : S\U_ `4BF [f «) )1 B 0F / B 9! M& 04 q ` p 0;- . A B 8 )7 & 9 q /- 0= r 74 = 0+4B :» 0= B EF > # c s 3tu p4= > 0=6 9 # 0= * 0 P1 0 p4= c38 / S_S ! 0)v H< # > ) 0= 7. 0 P1 A = 9 w c ! H, 41 % =, [ . * )% ] `! )J/ ... ) 7 H 41 )B Nw4i7 Nw > 0= 9J 0F 8 B 76 ) 0I7 # B * $0 P1 A7 & $ y ! a )1 $0 p4= $0= = {t86 3$ » > y) 0 P1 z = a ! # )J/ > & a ! , <P1 & ) C)}L 1 0HFi ) 0I7 )6 24u & H 4w1 $?| $ 0 IF $56)7 y) a )1 $0. -

) 4 2012;9( Ience Journal Life Sc 1739

Life Science Journal 2012;9(4) http://www.lifesciencesite.com Analysis of Totemic Cow and its Association with the Fereydoun Family in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh Masoumeh Zandie1, Kheironnesa Mohammadpour2*and Nahid Sharifi3 1 Department of Persian Literature, Payame-Nour University, Iran E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Persian Literature, Payame-Nour University, Iran E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of English Literature, Payame-Nour University, Iran *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: The origin and source of national epics are old oral tales that are conveyed to the future generations and also are recorded in epic works. Hence, these works reflect the thoughts, ideas, and rituals of the nation they belong. Moreover, since totem and totemism is an old ritual that dates back to the distant past of most of the nations, it is reflected in the form of epic. This paper particularly deals with the manifestation and embodiment of totemic cow in the Shahnameh and its association with Fereydoun’s Family. [Masoumeh Zandie, Kheironnesa Mohammadpour and Nahid Sharifi. Analysis of Totemic Cow and its Association with the Fereydoun Family in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh.. Life Sci J 2012;9(4):1739-1747] (ISSN:1097-8135). http://www.lifesciencesite.com. 265 Keywords: Totemism, Totem, the Shahnameh, Fereydoun, Cow Introduction mentioned that “In mythology, god is often embodied in Totem and totemism is discussed in books on the history the form of a certain animal” (Freud, 1976: 302). of religions (including A History of the World’s Based on the definition of totem, “in totemism, all the Religions by John Boyer Noss).