Thesis Final Corrections 180609

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fools Crow, James Welch

by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Office of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov Cover: #955-523, Putting up Tepee poles, Blackfeet Indians [no date]; Photograph courtesy of the Montana Historical Society Research Center Photograph Archives, Helena, MT. by James Welch Model Teaching Unit English Language Arts Secondary Level with Montana Common Core Standards Written by Dorothea M. Susag Published by the Montana Ofce of Public Instruction 2010 Revised 2014 Indian Education for All opi.mt.gov #X1937.01.03, Elk Head Kills a Buffalo Horse Stolen From the Whites, Graphite on paper, 1883-1885; digital image courtesy of the Montana Historical Society, Helena, MT. Anchor Text Welch, James. Fools Crow. New York: Viking/Penguin, 1986. Highly Recommended Teacher Companion Text Goebel, Bruce A. Reading Native American Literature: A Teacher’s Guide. National Council of Teachers of English, 2004. Fast Facts Genre Historical Fiction Suggested Grade Level Grades 9-12 Tribes Blackfeet (Pikuni), Crow Place North and South-central Montana territory Time 1869-1870 Overview Length of Time: To make full use of accompanying non-fiction texts and opportunities for activities that meet the Common Core Standards, Fools Crow is best taught as a four-to-five week English unit—and history if possible-- with Title I support for students who have difficulty reading. Teaching and Learning Objectives: Through reading Fools Crow and participating in this unit, students can develop lasting understandings such as these: a. -

Diversity in the City

Marco Martiniello, Brigitte Piquard Diversity in the City HumanitarianNet Thematic Network on Humanitarian Development Studies Diversity in the City Diversity in the City Edited by Marco Martiniello Brigitte Piquard University of Liège University of Louvain 2002 University of Deusto Bilbao No part of this publication, including the cover design, may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by and means, whether electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, recording or photocopying, without prior permission or the publisher. Publication printed in ecological paper Illustration of front page: Xabi Otero © Universidad de Deusto Apartado 1 - 48080 Bilbao I.S.B.N.: 84-7485-789-9 Legal Deposit: BI - 349-02 Printed in Spain/Impreso en España Design by: IPAR, S. Coop. - Bilbao Printed by: Artes Gráficas Rontegui, S.A.L. Contents Preface . 9 Introduction Marco Martiniello (University of Liège) and Brigitte Piquard (University of Louvain) . 11 Ethnic diversity and the city Ceri Peach (University of Oxford) . 21 Citizenship and exclusion on Europe´s southern frontier: the case of El Ejido Almudena Garrido (University of Deusto) . 43 When de-segregation produces stigmatisation: ethnic minorities and urban policies in France Patrick Simon (Institut National d'Études Démographiques) . 61 The study of community development in the city. Diversity as a tool Ruth Soenen and Mac Verlot (University of Gent) . 95 The Latinisation of the United States: social inequalities and cultural obsessions James Cohen (University Paris-VIII) . 111 Western Europe in the Urban Gap Between Mobility and Migration Flows Barbara Verlic Christensen (University of Ljubljana) . 135 Diasporic identities and diasporic economies: the case of minority ethnic media Charles Husband (University of Bradford) . -

Senator Hee Says UHM's Strategic Plan Has Room for Improvement

Inside Features 2,7 Sports 3 Thursday Editorials 4, 5 February 23, 2006 Comics 6 Surf 8 VOL. 100 | ISSUE 105 Serving the students of the University of Hawai‘i at Manoa since 1922 WWW.KALEO.ORG ‘Date Movie’ Use the right is a gross board for the waste of time right conditions Features | Page 2 Surf | Page 8 Senator Hee says UHM’s Strategic SoJ plays Campus Center Plan has room for improvement By Alana Folen many different and complex arrays Konan told the committee that Ka Leo Contributing Writer of units that we have under our the university is on schedule with campus,” Konan said. “We have the time line put forth by the criti- At a recent informational brief- a very complicated university. We cal financial audit report of UHM ing, Sen. Clayton Hee, chair of the have many units. We are serving given to the legislature in Dec. Committee on Higher Education, many different functions, and to 2005 by the state auditor. In the criticized the University of Hawai‘i me there’s a great value in trying past year, Konan said the budget at Manoa’s Strategic Plan, saying to bring some simplicity to that. level summary has been reconfig- it was too brief and “needs to be And this plan has served a really ured to show data at the unit level, beefed up.” useful function – when I go to quarterly financial reports have “When you review the plan, meetings people do quote from the been posted on the Web to enhance it’s very broad,” Hee told UHM plan and there are parts of the plan the transparency of operations, interim Chancellor Denise Konan that really help to guide and moti- and a Campus Planning Day was and UH system-wide Chief vate members of my community.” hosted in October with 250 cam- Financial Officer Howard Todo. -

A Million Little Maybes: the James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover Or Jacket As Commercial Speech

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 17 Volume XVII Number 1 Volume XVII Book 1 Article 5 2006 A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech Samantha J. Katze Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Samantha J. Katze, A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech, 17 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 207 (2006). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol17/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech Cover Page Footnote The author would like to thank Professor Susan Block-Liebe for helping the author formulate this Note and the IPLJ staff for its assistance in the editing process. This note is available in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol17/iss1/5 KATZE_FORMATTED_102606.DOC 11/1/2006 12:06 PM A Million Little Maybes: The James Frey Scandal and Statements on a Book Cover or Jacket as Commercial Speech Samantha J. -

THROWING BOOKS INSTEAD of SPEARS: the Alexie-Treuer Skirmish Over Market Share

THROWING BOOKS INSTEAD OF SPEARS: The Alexie-Treuer Skirmish Over Market Share Ezra Whitman Critical Paper and Program Bibliography Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MFA (Master of Fine Arts) in Creative Writing, Pacific Lutheran University, August 2011 1 Throwing Books Instead of Spears: The Alexie-Treuer Skirmish Over Market Share Following the 2006 publication of David Treuer’s Native American Fiction: A User’s Manual, Minneapolis-based publication Secrets of the City interviewed Spokane/Coeur D’Alene Indian writer Sherman Alexie. This gave Alexie an opportunity to respond to the User’s Manual’s essay “Indian/Not-Indian Literature” in which the Ojibwe writer points out the tired phrases and flawed prose of Alexie’s fiction. “At one point,” Alexie said in his interview with John Lurie, “when [Treuer’s] major publishing career wasn’t going well, I helped him contact my agent. I’m saying this stuff because this is where he lives and I want the world to know this: He wrote a book to show off for white folks, and we Indians are giggling at him.” Alexie takes the debate out of the classroom into the schoolyard by summoning issues that deal less with literature, and more with who has more successfully navigated the Native American fiction market. Insecurities tucked well beneath this pretentious “World’s Toughest Indian” exterior, Alexie interviews much the way he writes: on the emotive level. He steers clear of the intellectual channels Treuer attempts to open, and at the basis this little scuffle is just that—a mismatch of channels; one that calls upon intellect, the other on emotion. -

Race and Ethnicity: What Are Their Roles in Gang Membership?

U.S. Department of Justice U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Justice Programs Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Institute of Justice National Center for Injury Prevention and Control CHANGING COURSE Preventing Gang Membership Chapter 10. Race and Ethnicity: What Are Their Roles in Gang Membership? NCJ 243474 Race and Ethnicity: What Are Their Roles in Gang Membership? Adrienne Freng and Terrance J. Taylor • The roles of race and ethnicity in gang membership are becoming increasingly complicated, and it is important to understand that the term gang membership is not “code” for race or ethnicity; the truth is that more and more gangs include white gang members and are becoming multiracial. • Different risk factors exist — and young people give different reasons — for gang-joining; how- ever, most risk factors cut across racial and ethnic lines, including the negative consequences associated with poverty, immigration, discrimination and social isolation, such as limited edu- cational opportunities, low parental monitoring and drug use. • To prevent gang-joining, resources should be used to revitalize deteriorating, poverty- stricken, racially/ethnically isolated communities. • We can act now on what we know about shared risk factors — such as poverty, immigration, discrimination and social isolation — to implement general prevention strategies and programs that are racially, ethnically and culturally sensitive while continuing to explore whether additional racially and ethnically specific gang-membership -

Endgame, Book 3) Pdf, Epub, Ebook

RULES OF THE GAME (ENDGAME, BOOK 3) PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Frey | 336 pages | 29 Dec 2016 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007586462 | English | London, United Kingdom Rules of the Game (Endgame, Book 3) PDF Book Read more So she makes a choice that surprises everyone, including herself. The only thing it says is they embrace.. Other editions. Frey for being able to create such an informative and objective narrator, by describing the body language, reactions and surroundings more than inner thoughts which in turn gave it more of a movie like perspective where we watch Endgame but do not participate, and it haunted my mind and made me question things. So our heroes will have no choice but to rebel. The book, according to the rules, will have many clues for solving the puzzles, or it may lead you to new puzzles online. La llamada Endgame Series 1. There are too many questions unanswered which bothered me like nothing else and the useless characters who got involved for literally nothing just made no sense at all. He survived the Scorch. If the only way to save the world was to destroy what you loved most, would you do it? Start your review of Rules of the Game Endgame, 3. Then earth had time to do something like shoot a rocket to destroy it. Escape the Present with These 24 Historical Romances. View all 8 comments. But when their paths intertwine, the last thing they expect is to let their guards down and work together. Most recently he has published Bright Shiny Morning, and his new book The Final Testament of the Holy Bible will publish on 12 April and is available for pre-order now. -

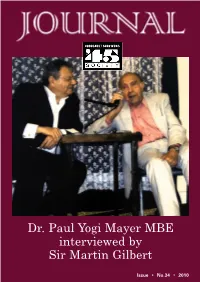

Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE Interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert

JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 1 Dr. Paul Yogi Mayer MBE interviewed by Sir Martin Gilbert Issue • No.34 • 2010 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 2 CH ARTER ED AC C OU NTANTS MARTIN HELLER 5 North End Road • London NW11 7RJ Tel 020 8455 6789 • Fax 020 8455 2277 email: [email protected] REGISTERED AUDIT ORS simmons stein & co. SOLI CI TORS Compass House, Pynnacles Close, Stanmore, Middlesex HA7 4AF Telephone 020 8954 8080 Facsimile 020 8954 8900 dx 48904 stanmore web site www.simmons-stein.co.uk Gary Simmons and Jeffrey Stein wish the ’45 Aid every success 2 JOURNAL 2010:JOURNAL 2010 24/2/10 12:04 Page 3 THE ’45 AID SOCIETY (HOLOCAUST SURVIVORS) PRESIDENT SECRETARY SIR MARTIN GILBERT C.B.E.,D.LITT., F.R.S.L M ZWIREK 55 HATLEY AVENUE, BARKINGSIDE, VICE PRESIDENTS IFORD IG6 1EG BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. (SOUTHAMPTON) COMMITTEE MEMBERS LORD GREVILLE JANNER OF M BANDEL (WELFARE OFFICER), BRAUNSTONE Q.C. S FREIMAN, M FRIEDMAN, PAUL YOGI MAYER M.B.E. V GREENBERG, S IRVING, ALAN MONTEFIORE, FELLOW OF BALLIOL J KAGAN, B OBUCHOWSKI, COLLEGE, OXFORD H OLMER, I RUDZINSKI, H SPIRO, DAME SIMONE PRENDEGAST D.B.E., J.P., D.L. J GOLDBERGER, D PETERSON, KRULIK WILDER HARRY SPIRO SECRETARY (LONDON) MRS RUBY FRIEDMAN CHAIRMAN BEN HELFGOTT M.B.E., D.UNIV. SECRETARY (MANCHESTER) (SOUTHAMPTON) MRS H ELLIOT VICE CHAIRMAN ZIGI SHIPPER JOURNAL OF THE TREASURER K WILDER ‘45 AID SOCIETY FLAT 10 WATLING MANSIONS, EDITOR WATLING STREET, RADLETT, BEN HELFGOTT HERTS WD7 7NA All submissions for publication in the next issue (including letters to the Editor and Members’ News Items) should be sent to: RUBY FRIEDMAN, 4 BROADLANDS, HILLSIDE ROAD, RADLETT, HERTS WD7 7BX ACK NOW LE DG MEN TS SALEK BENEDICT for the cover design. -

Native American Literature

ENGL 5220 Nicolas Witschi CRN 15378 Sprau 722 / 387-2604 Thursday 4:00 – 6:20 office hours: Wednesday 12:00 – 2:00 Brown 3002 . and by appointment e-mail: [email protected] Native American Literature Over the course of the last four decades or so, literature by indigenous writers has undergone a series of dramatic and always interesting changes. From assertions of sovereign identity and engagements with entrenched cultural stereotypes to interventions in academic and critical methodologies, the word-based art of novelists, dramatists, critics, and poets such as Sherman Alexie, Louise Erdrich, Louis Owens, N. Scott Momaday, Leslie Marmon Silko, Simon Ortiz, and Thomas King, among many others, has proven vital to our understanding of North American culture as a whole. In this course we will examine a cross-section of recent and exemplary texts from this wide-reaching literary movement, paying particular attention to the formal, thematic, and critical innovations being offered in response to questions of both personal and collective identity. This course will be conducted seminar-style, which means that everyone is expected to contribute significantly to discussion and analysis. TEXTS: The following texts are available at the WMU Bookstore: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, by Sherman Alexie (Spokane) The Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse, by Louise Erdrich (Anishinaabe) Bloodlines: Odyssey of a Native Daughter, by Janet Campbell Hale (Coeur d'Alene) The Light People, by Gordon D. Henry (Anishinaabe) Green Grass, Running Water, by Thomas King (Cherokee) House Made of Dawn, by N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa) from Sand Creek, by Simon Ortiz (Acoma) Nothing But The Truth, eds. -

Spring 1986 Editor: the Cover Is the Work of Lydia Sparrow

'sReview Spring 1986 Editor: The cover is the work of Lydia Sparrow. J. Walter Sterling Managing Editor: Maria Coughlin Poetry Editor: Richard Freis Editorial Board: Eva Brann S. Richard Freis, Alumni representative Joe Sachs Cary Stickney Curtis A. Wilson Unsolicited articles, stories, and poems are welcome, but should be accom panied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope in each instance. Reasoned comments are also welcome. The St. John's Review (formerly The Col lege) is published by the Office of the Dean. St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. William Dyal, Presi dent, Thomas Slakey, Dean. Published thrice yearly, in the winter, spring, and summer. For those not on the distribu tion list, subscriptions: $12.00 yearly, $24.00 for two years, or $36.00 for three years, paya,ble in advance. Address all correspondence to The St. John's Review, St. John's College, Annapolis, Maryland 21404. Volume XXXVII, Number 2 and 3 Spring 1986 ©1987 St. John's College; All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without permission is prohibited. ISSN 0277-4720 Composition: Best Impressions, Inc. Printing: The John D. Lucas Printing Company Contents PART I WRITINGS PUBLISHED IN MEMORY OF WILLIAM O'GRADY 1 The Return of Odysseus Mary Hannah Jones 11 God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob Joe Sachs 21 On Beginning to Read Dante Cary Stickney 29 Chasing the Goat From the Sky Michael Littleton 37 The Miraculous Moonlight: Flannery O'Connor's The Artificial Nigger Robert S. Bart 49 The Shattering of the Natural Order E. A. Goerner 57 Through Phantasia to Philosophy Eva Brann 65 A Toast to the Republic Curtis Wilson 67 The Human Condition Geoffrey Harris PART II 71 The Homeric Simile and the Beginning of Philosophy Kurt Riezler 81 The Origin of Philosophy Jon Lenkowski 93 A Hero and a Statesman Douglas Allanbrook Part I Writings Published in Memory of William O'Grady THE ST. -

Novelty and Canonicity in Lucian's Verae Historiae

Parody and Paradox: Novelty and Canonicity in Lucian’s Verae Historiae Katharine Krauss Barnard College Comparative Literature Class of 2016 Abstract: The Verae historiae is famous for its paradoxical claim both condemning Lucian’s literary predecessors for lying and also confessing to tell no truths itself. This paper attempts to tease out this contradictory parallel between Lucian’s own text and the texts of those he parodies even further, using a text’s ability to transmit truth as the grounds of comparison. Focusing on the Isle of the Blest and the whale episodes as moments of meta-literary importance, this paper finds that Lucian’s text parodies the poetic tradition for its limited ability to transmit truth, to express its distance from that tradition, and yet nevertheless to highlight its own limitations in its communication of truth. In so doing, Lucian reflects upon the relationship between novelty and adherence to tradition present in the rhetoric of the Second Sophistic. In the prologue of his Verae historiae, Lucian writes that his work, “τινα…θεωρίαν οὐκ ἄµουσον ἐπιδείξεται” (1.2).1 Lucian flags his work as one that will undertake the same project as the popular rhetorical epideixis since the Verae historiae also “ἐπιδείξεται.” Since, as Tim Whitmarsh writes, “sophistry often privileges new ideas” (205:36-7), Lucian’s contemporary audience would thus expect his text to entertain them at least in part through its novelty. Indeed, the Verae historiae fulfills these expectations by offering a new presentation of the Greek literary canon. In what follows I will first explore how Lucian’s parody of an epic katabasis in the Isle of the Blest episode criticizes the ability of the poetic tradition to transmit truth. -

Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2017 Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika Lauren Jordan Wood College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Wood, Lauren Jordan, "Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus' Aithiopika" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1004. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1004 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus’ Aithiopika A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Classical Studies from The College of William and Mary by Lauren Wood Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ William Hutton, Director ________________________________________ Vassiliki Panoussi ________________________________________ Suzanne Hagedorn Williamsburg, VA April 17, 2017 Wood 2 Kalasiris and Charikleia: Mentorship and Intertext in Heliodorus’ Aithiopika Odyssean and more broadly Homeric intertext figures largely in Greco-Roman literature of the first to third centuries AD, often referred to in scholarship as the period of the Second Sophistic.1 Second Sophistic authors work cleverly and often playfully with Homeric characters, themes, and quotes, echoing the traditional stories in innovative and often unexpected ways. First to fourth century Greek novelists often play with the idea of their protagonists as wanderers and exiles, drawing comparisons with the Odyssey and its hero Odysseus.