The Complete Hate – Peter Bagge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

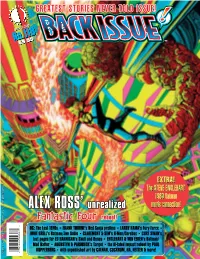

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

Alter Ego #78 Trial Cover

TwoMorrows Publishing. Celebrating The Art & History Of Comics. SAVE 1 NOW ALL WHE5% O N YO BOOKS, MAGS RDE U & DVD s ARE ONL R 15% OFF INE! COVER PRICE EVERY DAY AT www.twomorrows.com! PLUS: New Lower Shipping Rates . s r Online! e n w o e Two Ways To Order: v i t c e • Save us processing costs by ordering ONLINE p s e r at www.twomorrows.com and you get r i e 15% OFF* the cover prices listed here, plus h t 1 exact weight-based postage (the more you 1 0 2 order, the more you save on shipping— © especially overseas customers)! & M T OR: s r e t • Order by MAIL, PHONE, FAX, or E-MAIL c a r at the full prices listed here, and add $1 per a h c l magazine or DVD and $2 per book in the US l A for Media Mail shipping. OUTSIDE THE US , PLEASE CALL, E-MAIL, OR ORDER ONLINE TO CALCULATE YOUR EXACT POSTAGE! *15% Discount does not apply to Mail Orders, Subscriptions, Bundles, Limited Editions, Digital Editions, or items purchased at conventions. We reserve the right to cancel this offer at any time—but we haven’t yet, and it’s been offered, like, forever... AL SEE PAGE 2 DIGITIITONS ED E FOR DETAILS AVAILABL 2011-2012 Catalog To get periodic e-mail updates of what’s new from TwoMorrows Publishing, sign up for our mailing list! ORDER AT: www.twomorrows.com http://groups.yahoo.com/group/twomorrows TwoMorrows Publishing • 10407 Bedfordtown Drive • Raleigh, NC 27614 • 919-449-0344 • FAX: 919-449-0327 • e-mail: [email protected] TwoMorrows Publishing is a division of TwoMorrows, Inc. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

Drawn & Quarterly |

DRAWN & QUARTERLY WINTER 2019 OFF SEASON JAMES STURM THIS WOMAN’S WORK JULIE DELPORTE CREDO: THE ROSE WILDER lANE storY PETER BAGGE LEAVING RICHARD’S VALLEY MICHAEL DEFORGE kitaro’S yOKAI battLES SHIGERU MIzUkI WALT AND SKEEZIX 1933-1934: VOLUME 7 FRANk kING EDITED BY CHRIS WARE AND JEET HEER OFF SEASON james sturm Rage. Depression. Divorce. Politics. Love. A visceral story that you can see, taste, and feel How could this happen? The question of A truly human experience, Off Season 2016 becomes deeply personal in James displays Sturm’s masterful pacing and Sturm’s riveting graphic novel Off Season, storytelling combined with conscious which charts one couple’s divisive sepa- and confident growth as the celebrated ration through the fall of 2016—during cartoonist and educator moves away from Bernie’s loss to Hillary, Hillary’s loss to historical fiction to deliver this long-form Trump, and the disorienting months narrative set in contemporary times. that followed. Originally serialized on Slate, this We see a father navigating life as a expanded edition turns timely vignettes single parent and coping with the disin- into a timeless, deeply affecting account tegration of a life-defining relationship. of one family and their off season. Amid the upheaval are tender moments with his kids—a sleeping child being PRAISE FOR jAMES STURM carried in from the car, Christmas morn- “Mr. Sturm knows when to let the images ing anticipation, a late-night cookie after speak for themselves.”—New York Times a temper tantrum—and fallible humans drenched in palpable feelings of grief, “James Sturm’s graphic narratives are rage, loss, and overwhelming love. -

Nieuwigheden Anderstalige Strips 2014

NIEUWIGHEDEN ANDERSTALIGE STRIPS 2014 WEEK 2 Engels All New X-Men 1: Yesterday’s X-Men (€ 19,99) (Stuart Immonen & Brian Mickael Bendis / Marvel) All New X-Men / Superior Spider-Men / Indestructible Hulk: The Arms of The Octopus (€ 14,99) (Kris Anka & Mike Costa / Marvel) Avengers A.I.: Human After All (€ 16, 99) (André Araujo & Sam Humphries / Marvel) Batman: Arkham Unhinged (€ 14,99) (David Lopez & Derek Fridols / DC Comics) Batman Detective Comics 2: Scare Tactics (€ 16,99) (Tony S. Daniel / DC Comics) Batman: The Dark Knight 2: Cycle of Violence (€ 14,99) (David Finch & Gregg Hurwitz / DC Comics) Batman: The TV Stories (€ 14,99) (Diverse auteurs / DC Comics) Fantastic Four / Inhumans: Atlantis Rising (€ 39,99) (Diverse auteurs / Marvel) Simpsons Comics: Shake-Up (€ 15,99) (Studio Matt Groening / Bongo Comics) Star Wars Omnibus: Adventures (€ 24,99) (Diverse auteurs / Dark Horse) Star Wars Omnibus: Dark Times (€ 24,99) (Diverse auteurs / Dark Horse) Superior Spider-Men Team-Up: Friendly Fire (€ 17,99) (Diverse auteurs / Marvel) Swamp Thing 1 (€ 19,99) (Roger Peterson & Brian K. Vaughan / Vertigo) The Best of Wonder Wart-Hog (€ 29,95) (Gilbert Shelton / Knockabout) West Coast Avengers: Sins of the Past (€ 29,99) (Al Milgrom & Steve Englehart / Marvel) Manga – Engelstalig: Naruto 64 (€ 9,99) (Masashi Kishimoto / Viz) Naruto: Three-in-One 7 (€ 14,99) (Masashi Kishimoto / Viz) Marvel Omnibussen in aanbieding !!! Avengers: West Coast Avengers vol. 1 $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! Marvel Now ! $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! Punisher by Rick Remender $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! The Avengers vol. 1 $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! Ultimate Spider-Man: Death of Spider-Man $ 75 NU: 39,99 Euro !!! Untold Tales of Spider-Man $ 99,99 NU: 49,99 Euro !!! X-Force vol. -

Writing About Comics

NACAE National Association of Comics Art Educators English 100-v: Writing about Comics From the wild assertions of Unbreakable and the sudden popularity of films adapted from comics (not just Spider-Man or Daredevil, but Ghost World and From Hell), to the abrupt appearance of Dan Clowes and Art Spiegelman all over The New Yorker, interesting claims are now being made about the value of comics and comic books. Are they the visible articulation of some unconscious knowledge or desire -- No, probably not. Are they the new literature of the twenty-first century -- Possibly, possibly... This course offers a reading survey of the best comics of the past twenty years (sometimes called “graphic novels”), and supplies the skills for reading comics critically in terms not only of what they say (which is easy) but of how they say it (which takes some thinking). More importantly than the fact that comics will be touching off all of our conversations, however, this is a course in writing critically: in building an argument, in gathering and organizing literary evidence, and in capturing and retaining the reader's interest (and your own). Don't assume this will be easy, just because we're reading comics. We'll be working hard this semester, doing a lot of reading and plenty of writing. The good news is that it should all be interesting. The texts are all really good books, though you may find you don't like them all equally well. The essays, too, will be guided by your own interest in the texts, and by the end of the course you'll be exploring the unmapped territory of literary comics on your own, following your own nose. -

Books Added in May Fiction

Books Added in May Fiction – May, 2017 Ahlborn, Ania, The devil crept in / Ania Ahlborn. FICTION AHL Alyan, Hala, 1986- Salt houses / Hala Alyan. FICTION ALY Ball, Bethany, What to do about the Solomons / Bethany Ball. FICTION BAL Blauner, Peter, Proving ground / Peter Blauner. FICTION BLA Brown, Dale, 1956- Price of duty / Dale Brown. FICTION BRO Brown, Taylor, 1982- The river of kings / Taylor Brown. FICTION BRO Buntin, Julie, Marlena : a novel / Julie Buntin. FICTION BUN Cameron, Claire, 1973- The last Neanderthal / Claire Cameron. FICTION CAM Cameron, W. Bruce, A dog's way home / W. Bruce Cameron. FICTION CAM Canty, Kevin, The underworld / Kevin Canty. FICTION CAN Chevalier, Tracy, New boy / Tracy Chevalier. FICTION CHE Child, Lee, No middle name : the complete collected Jack Reacher short stories / Lee Child. FICTION CHI Child, Lincoln, Full wolf moon / Lincoln Child. FICTION CHI Cole, Alyssa, An extraordinary union : a novel of the Civil War / Alyssa Cole. FICTION COL Cottrell, Patty Yumi, Sorry to disrupt the peace / Patty Yumi Cottrell. FICTION COT Craig, Charmaine, Miss Burma / Charmaine Craig. FICTION CRA Crichton, Michael, 1942-2008, Dragon teeth / Michael Crichton. FICTION CRI Cussler, Clive, Nighthawk : a novel from the NUMA Files / Clive Cussler and Graham Brown. FICTION CUS Great American short stories : from Hawthorne to Hemingway / edited with an introduction by Corinne Demas. SSA FICTION GRE Drew, Alan, 1970- Shadow man / Alan Drew. FICTION DRE Dymott, Elanor, 1973- Silver and salt / Elanor Dymott. FICTION DYM Elsberg, Marc, 1967- Blackout / Marc Elsberg ; translated by Marshall Yarbrough. FICTION ELS Emmich, Val, The reminders / Val Emmich. FICTION EMM Evans, Richard Paul, The broken road / Richard Paul Evans. -

Mcwilliams Ku 0099D 16650

‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry © 2019 By Ora Charles McWilliams Submitted to the graduate degree program in American Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Henry Bial Germaine Halegoua Joo Ok Kim Date Defended: 10 May, 2019 ii The dissertation committee for Ora Charles McWilliams certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: ‘Yes, But What Have You Done for Me Lately?’: Intersections of Intellectual Property, Work-for-Hire, and The Struggle of the Creative Precariat in the American Comic Book Industry Co-Chair: Ben Chappell Co-Chair: Elizabeth Esch Date Approved: 24 May 2019 iii Abstract The comic book industry has significant challenges with intellectual property rights. Comic books have rarely been treated as a serious art form or cultural phenomenon. It used to be that creating a comic book would be considered shameful or something done only as side work. Beginning in the 1990s, some comic creators were able to leverage enough cultural capital to influence more media. In the post-9/11 world, generic elements of superheroes began to resonate with audiences; superheroes fight against injustices and are able to confront the evils in today’s America. This has created a billion dollar, Oscar-award-winning industry of superhero movies, as well as allowed created comic book careers for artists and writers. -

Drawn & Quarterly Debuts on Comixology and Amazon's Kindle

Drawn & Quarterly debuts on comiXology and Amazon’s Kindle Store September 15th, 2015 — New York, NY— Drawn & Quarterly, comiXology and Amazon announced today a distribution agreement to sell Drawn & Quarterly’s digital comics and graphic novels across the comiXology platform as well as Amazon’s Kindle Store. Today’s debut sees such internationally renowned and bestselling Drawn & Quarterly titles as Lynda Barry’s One! Hundred! Demons; Guy Delisle’s Jerusalem: Chronicles from the Holy City; Rutu Modan’s Exit Wounds and Anders Nilsen’s Big Questions available on both comiXology and the Kindle Store “It is fitting that on our 25th anniversary, D+Q moves forward with our list digitally with comiXology and the Kindle Store,” said Drawn & Quarterly Publisher Peggy Burns, “ComiXology won us over with their understanding of not just the comics industry, but the medium itself. Their team understands just how carefully we consider the life of our books. They made us feel perfectly at ease and we look forward to a long relationship.” “Nothing gives me greater pleasure than having Drawn & Quarterly’s stellar catalog finally available digitally on both comiXology and Kindle,” said David Steinberger, comiXology’s co-founder and CEO. “D&Q celebrate their 25th birthday this year, but comiXology and Kindle fans are getting the gift by being able to read these amazing books on their devices.” Today’s digital debut of Drawn & Quarterly on comiXology and the Kindle Store sees all the following titles available: Woman Rebel: The Margaret Sanger Story by -

Suggested Graphic Novels for Secondary Students

Suggested Reading Graphic novels – Middle and High school level My Summers with Buster by Matt Phelan Astronaut Academy: Zero Gravity by Dave Roman The Other Side of the Wall by Simon Schwartz Nothing Can Possibly Go Wrong by Prudence Shen Nimona by Noelle Stevenson Drama by Raina Telgemeier Cardboard by Doug TenNapel Ghostopolis by Doug TenNapel Bad Island by Doug TenNapel Trickster: Native American Tales: A Graphic Collection. edited by Matt Dembicki Fulcrum, Princess Decomposia and Count Spatula by Andi Watson Curses! Foiled again by Jane Yolen The sequel to Foiled! by Jane Yolen A Game for Swallows: To Die, to Leave, to Return by Zeina Abirached Fantasy Sports by Sam Bosma Jane, the Fox and Me by Fanny Britt Anya’s Ghost by Vera Brosgol Awkward by Svetlana Chmakova Hereville: How Mirka Got Her Sword by Barry Deutsch Gaijin: American Prisoner of War by Matt Faulkner The Dumbest Idea Ever! by Jimmy Gownley Howtoons: Tools Of Mass Construction by Saul Griffith, Nick Dragotta, and Joost Bonsen, Page by Paige by Laura Lee Gulledge Marble Season by Gilbert Hernandez Friends with Boys by Faith Erin Hicks Sunny Side Up by Jennifer L. Holm and Matthew Holm Child Soldier When Boys and Girls are Used in War by Jessica Dee Humphreys and Michel Chikwanine, Anne Frank: The Anne Frank House Authorized Graphic Biography by Sid Jacobson Roller Girl by Victoria Jamieson A Bag of Marbles: The Graphic Novel by Joseph Joffo, The Stratford Zoo Midnight Revue Presents Macbeth by Ian Lendler, Little White Duck: A Childhood in China by Andrés Vera Martínez and Na Liu Baba Yaga’s Assistant by Marika McCoola Best Shot in the West: The Adventures of Nat Love by Patricia C. -

Nominees Announced for 2017 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards Sonny Liew’S the Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye Tops List with Six Nominations

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Jackie Estrada [email protected] Nominees Announced for 2017 Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye Tops List with Six Nominations SAN DIEGO – Comic-Con International (Comic-Con) is proud to announce the nominations for the Will Eisner Comic Industry Awards 2017. The nominees were chosen by a blue-ribbon panel of judges. Once again, this year’s nominees reflect the wide range of material being published in comics and graphic novel form today, with over 120 titles from some 50 publishers and by creators from all over the world. Topping the nominations is Sonny Liew’s The Art of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (Pantheon), originally published in Singapore. It is a history of Singapore from the 1950s to the present as told by a fictional cartoonist in a wide variety of styles reflecting the various time periods. It is nominated in 6 categories: Best Graphic Album–New, Best U.S. Edition of International Material–Asia, Best Writer/Artist, Best Coloring, Best Lettering, and Best Publication Design. Boasting 4 nominations are Image’s Saga and Kill or Be Killed. Saga is up for Best Continuing Series, Best Writer (Brian K. Vaughan), and Best Cover Artist and Best Coloring (Fiona Staples). Kill or Be Killed by Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips is nominated for Best Continuing Series, Best Writer, Best Cover Artist, and Best Coloring (Elizabeth Breitweiser). Two titles have 3 nominations: Image’s Monstress by Marjorie Liu and Sana Takeda (Best Publication for Teens, Best Painter, Best Cover Artist) and Tom Gauld’s Mooncop (Best Graphic Album–New, Best Writer/Artist, Best Lettering), published by Drawn & Quarterly.