The Road Ahead ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Global Monthly Is Property of John Doe Total Toyota Brand

A publication from April 2012 Volume 01 | Issue 02 global europe.autonews.com/globalmonthly monthly Your source for everything automotive. China beckons an industry answers— How foreign brands are shifting strategies to cash in on the world’s biggest auto market © 2012 Crain Communications Inc. All rights reserved. March 2012 A publication from Defeatglobal spurs monthly dAtA Toyota’s global Volume 01 | Issue 01 design boss Will Zoe spark WESTERN EUROPE SALES BY MODEL, 9 MONTHSRenault-Nissan’sbrought to you courtesy of EV push? www.jato.com February 9 months 9 months Unit Percent 9 months 9 months Unit Percent 2011 2010 change change 2011 2010 change change European sales Scenic/Grand Scenic ......... 116,475 137,093 –20,618 –15% A1 ................................. 73,394 6,307 +67,087 – Espace/Grand Espace ...... 12,656 12,340 +316 3% A3/S3/RS3 ..................... 107,684 135,284 –27,600 –20% data from JATO Koleos ........................... 11,474 9,386 +2,088 22% A4/S4/RS4 ..................... 120,301 133,366 –13,065 –10% Kangoo ......................... 24,693 27,159 –2,466 –9% A6/S6/RS6/Allroad ......... 56,012 51,950 +4,062 8% Trafic ............................. 8,142 7,057 +1,085 15% A7 ................................. 14,475 220 +14,255 – Other ............................ 592 1,075 –483 –45% A8/S8 ............................ 6,985 5,549 +1,436 26% Total Renault brand ........ 747,129 832,216 –85,087 –10% TT .................................. 14,401 13,435 +966 7% RENAULT ........................ 898,644 994,894 –96,250 –10% A5/S5/RS5 ..................... 54,387 59,925 –5,538 –9% RENAULT-NISSAN ............ 1,239,749 1,288,257 –48,508 –4% R8 ................................ -

Clock Spring

TEMCO INTERNATIONAL LIMITED E X P E R T I S E L E A D E X C E L L E N C E Http:www.0086parts.com Email: [email protected] CLOCK SPRING RoHS TS16949 COMPLIANCE OEM NO. APPLICATION PICTURE 84306-06140 Prius Rav4 Camry Scion 2.7L 84307-47020 Lexus 2007 84306-48030 Pontiac Vibe 2009-2010 84306-06110 corolla 2009-2013 84306-0N010 Highlander 2010-2012 84306-30090 matrix 2009-2010 84306-0K010 tacoma 2005-2013 84306-04080 Land Cruiser Prado GRJ150 84306-0E010 ISUZU D-MAX ALL NEW 84306-47020 PICKUP UTE 2012-PRESENT 84306-06030 84306-0D070 84306-42020 04004-07122 84306-12070 84306-12170 Solara Tacoma Tundra 84306-0C021 Avalon 2000-2003 84306-60050 Sequoia 2001-2003 84306-35011 COROLLA 84306-08030 84306-35010 84306-30120 84306-07030 84306-20050 84306-0C010 84306-08030 84306-35010 84306-0k020 Toyota Hilux 84306-0K021 2005-2013 84306-0H010 VIGO 84306-06120 INNOVA1 84306-12160 84307-12100 2016 VIGO NEW 84306-06190 Toyota Corrolla 2010-2016 84306-0k120 Toyota Hilux Innova Fortuner 84306-06180 GGN155 2015 - 2018 84306-02310 TEMCO INTERNATIONAL LIMITED TEMCO INTERNATIONAL LIMITED E X P E R T I S E L E A D E X C E L L E N C E Http:www.0086parts.com Email: [email protected] CLOCK SPRING RoHS TS16949 COMPLIANCE OEM NO. APPLICATION PICTURE 84306-06210 Toyota Aurion Camry Corolla 84306-09030 TOYOTA 84307-06090 Corolla Camry LandCruiser 84306-09020 Toyota Camry 2012-2014 New Camry 2013 84306-33080 Camry Corolla Matrix 84306-30090 2003-2008 Toyota 84306-02110 2002-2006 Toyota Camry 84306-05050 2004-2010 Toyota Sienna 84306-06030 2005-2010 Scion tC -

Hyundai Prijslijst Personenauto’S En Accessoires Per 1 Maart 2012 De Kracht Van Kwaliteit

Hyundai Prijslijst Personenauto’s en accessoires per 1 maart 2012 De kracht van kwaliteit U staat op het punt te kiezen voor het merk Hyundai, één van de grootste en succesvolste autofabrikanten ter wereld. Hyundai biedt wat kopers belangrijk vinden: een complete uitrusting en betaalbare topkwaliteit. Veiligheid, betrouwbaarheid en een stijlvolle uitstraling zijn daarbij vanzelfsprekend. Hyundai timmert hard aan de weg. Door omvangrijke inves- van Hyundai’s Europese Design Center zorgen daarnaast teringen in technologisch onderzoek en nieuwe modellen voor een dynamische, sympathieke en moderne styling die u heeft Hyundai een moderne generatie auto’s ontwikkeld die zeker zal aanspreken. Dankzij een efficiënte productie zijn nauwgezet zijn afgestemd op de smaak en stijl van de veel- de prijzen zeer concurrerend. eisende automobilist van nu. De combinatie van topkwaliteit, een sterk design en een aantrekkelijke prijs is uniek. Hyundai Het modellengamma van Hyundai is zeer uitgebreid. Alle biedt al deze voordelen. auto’s zijn voorzien van sterke en zuinige hightech benzine- of dieselmotoren die desgewenst zijn te koppelen aan een Bij de ontwikkeling van onze auto’s staat gebruik van hoog- automatische transmissie. Welke voorkeur en welk budget u waardig materiaal voorop. Doordachte constructies verfijnen ook hebt; er is altijd volop keuze. Dat verklaart het succes het productieproces, waardoor tijdens de fabricage van elke van ons merk wereldwijd en ook in Nederland, waar Hyundai Hyundai hoge kwaliteit altijd op de eerste plaats komt. Als al jaren tot de meest succesvolle en bestverkopende merken gevolg hiervan levert Hyundai veilige auto’s met hoge be- behoort. trouwbaarheid en een lage kilometerkostprijs. De ontwerpers 2 Hyundai ZEKERHEID Service op maat Wie voor Hyundai kiest, maakt een bewuste keuze voor een betrouwbare partner in mobiliteit. -

Le Programme Flotte De Hyundai Le Bon Format Pour Tout Business EDITORIAL SOMMAIRE Chères Lectrices, Chers Lecteurs

Le programme flotte de Hyundai Le bon format pour tout business EDITORIAL SOMMAIRE Chères lectrices, chers lecteurs Hyundai fait partie des plus grands constructeurs automobiles de la Portrait de Hyundai planète. C’est le résultat du pouvoir d’innovation de la marque, d’une pa- Développement en Suisse et dans le monde Page 3 lette de modèles attractive et plus encore d’un excellent niveau de qua- lité, étayé par une garantie d’usine au top niveau puisque chaque voiture Avantages pour l’exploitant de flotte de tourisme Hyundai est couverte cinq ans sans limite de kilométrage. Garanties et TCOs au sommet Page 4 Hyundai surfe sur la vague du succès depuis des années, aussi en Hyundai Fleet Business Center Europe et en Suisse. L’une des explications se trouve au Hyundai Motor Le meilleur des compétences flotte Page 5 Europe Technical Center de Rüsselsheim en Allemagne, où des ingénieurs chevronnés développent des voitures qui répondent aux besoins spéci- Hyundai i10 et i20 fiques des clients européens. Petite taille pour hautes exigences Page 6 Ces derniers mois, Hyundai a présenté un grand nombre de nouveaux Hyundai i20 Coupé et ix20 modèles attractifs. Parmi ceux-ci on peut citer la nouvelle génération de Plus de diversité en format urbain Page 7 la petite i20, la compacte i30 lancée récemment mais aussi la nouvelle représentante de classe moyenne i40 ainsi que l’utilitaire léger H350. Hyundai i30 Coupé, 5 portes et Wagon Avec ces modèles et bien d’autres encore, Hyundai occupe chaque seg- Trendsetter compact Page 8 ment important, de la citadine au robuste 3,5-tonnes. -

AUGUST NEW Item Information AUGUST

MK item/Interchange News Date: AUGUST 28, 2014 No. 14-08 AUGUST NEW Item Information BRAKE PAD Releasing Month Quotation MK No. Application (accepting order) Month HONDA BRIO D5217M Made in Indonesia AUGUST' 14 AUGUST' 14 FMSI № D1685 AUGUST NEW Item Drawing Information BRAKE PAD 1/3 Page Next coming up information MK No. MK No. D3163M K1286 Made in Indonesia Made in Japan/Indonesia FMSI № 1728 D6154M K9996 Made in Japan Made in Japan/Indonesia D11341 K1289 Made in Indonesia Made in Japan FMSI № S1020 D11342 Made in Indonesia D11344 Made in Indonesia D11346 Made in Indonesia FMSI № D894 D11347H Made in Indonesia D11349MH Made in Indonesia FMSI № D1467 NEW Regulation 90 approval Item(for EU market) As for the MK No. * marks, we have more OE No. information. If you want to know the more information, please e-mail to the following address. e-mail address : [email protected] In another way to find OE No. please use the Product Search in the MK Kashiyama web page. http://www.mkg.co.jp/global/en/product/search-by-part-number.html MK No. Application Approval No. D11129H DAEWOO Kalos 1.2 Petrol 04/03- E1 90R-011288/308 DAEWOO Kalos 1.4 Petrol 09/02- *WITH SHIM D11173MH * Hyundai Terracan 2.9 Diesel Turbo 12/03- E1 90R-01280/349 Hyundai Terracan 3.5 Petrol 12/03- *WITH SHIM Kia Opirus 3.5 Petrol 07/03-10/06 - CONTINUED TO NEXT PAGE - 2/3 Page D11198MH * Hyundai Santa Fe 2.2 Diesel Turbo 11/05- E1 90R-011288/400 Hyundai Santa Fe 2.7 Petrol 11/05- *WITH SHIM D11230MH * Hyundai IX35 1.6 Petrol 07/10- E1 90R-011288/427 Hyundai IX35 2.0 Petrol 01/10- *WITH -

Hyundai Kona Named “Best Car of the Year ABC 2019” in Spain

Hyundai Kona named “Best Car of the Year ABC 2019” in Spain Kona takes the most prestigious prize in the Spanish automotive industry Award recognises the many qualities of the Kona line-up, including the full electric model Fourth time Hyundai has claimed the title since 2008 December 13, 2018 – The All-New Hyundai Kona has won the ABC award for "Best Car of the Year 2019" in Spain. Granted by the newspaper ABC, and recognised as the most prestigious prize in the country’s automotive industry, this award is decided by a jury composed of 36 journalists from different media, newspapers, magazines, television, radio and agencies, as well as the public vote on the website of the newspaper ABC. The award takes into account both external and internal design, technology, reliability, performance, safety, as well as market segment, and the Kona convinced in all areas. It also recognises the overall quality of the vehicle as well as its five-year warranty. All previous winners of this award have become great successes for the brands they represent, and the same is expected for the Hyundai Kona. The Hyundai Kona is the first sub-compact SUV that adds a 100% electric version to its range of powertrains. “For Hyundai, getting this prestigious award is very satisfying, and it recognises the development of the brand in terms of technology, design and quality. And that an SUV like the Kona, which provides all the mobility needs demanded by society, takes the prize, as well as being a source of pride for all, also confirms the market trend towards recreational and leisure vehicles, which nevertheless comply with the expectations in terms of environment, fuel efficiency and so on,” said Leopoldo Satrustegui, Managing Director of Hyundai Motor España. -

WOW! Würth Online World Gmbh · Sitz Künzelsau · Registergericht Stuttgart HRB 590 686 Seite Geschäftsführer: Frank Konietzke, Svein Oftedal, Mario Weiß 8

Aggiornamento banca dati 5 . 0 0 . 1 4 Con questo aggiornamento sono stati implementati 382 modelli di veicoli. Questo porta ad una copertura totale di 1165 veicoli Panoramica produttori veicoli aggiornati: Abarth Isuzu Perodua Alfa Romeo Iveco Peugeot Audi Jaguar Piaggio BMW Jeep Porsche Chevrolet KIA Renault Chrysler Lancia Saab Citroën Land Rover Seat Dacia LDV Skoda Daihatsu Lexus Smart Daimler Mazda SsangYong Dodge Mercedes Benz Subaru Fiat MG Suzuki Ford Mini Toyota GWM Mitsubishi Vauxhall Honda Nissan Volkswagen Hyundai Opel Volvo Airbag BMW 2-series (F22/23/45/46) Toyota Corolla (E110) Chevrolet Malibu Toyota GT86 Chevrolet Trax Vauxhall Astra J Chrysler Ypsilon Vauxhall Meriva B Citroën C-Zero Vauxhall Vivaro Citroën C3 Picasso Volkswagen Caddy (2K) Citroën C4 Picasso/Grand Picasso 2 Volkswagen e-up! (B) Volvo C30 Citroën DS4 Volvo XC60 Dacia Dokker Citroën C3 Pluriel Fiat 500L Citroën DS3 Fiat Freemont Jaguar XJ (X351) Ford Ecosport ('13) Citroën C1 (B4) Ford Mondeo ('15) Citroën C4 Cactus (E3) Honda CR-V (IV) Citroën C4 Serie 2 Hyundai i10 (IA) Dacia Duster (HS) Hyundai i20 (GB/IB) Ford Focus ('11) Hyundai i800/iLoad/iMax Ford Grand Tourneo Connect ('14) Hyundai Veloster Ford Kuga ('13) Jaguar XF (X250) Ford Tourneo Connect ('14) Jeep Wrangler (YJ) Ford Tourneo Courier ('14) Mini Clubman (R55) Ford Tourneo Custom ('13) Mini Countryman (R60) Ford Transit ('14) Mini Coupe (R58) Ford Transit Connect ('13) Mini Roadster (R59) Ford -

(Page 1 of 3) J.D. Power Asia Pacific Reports: Chinese Domestic Auto

J.D. Power Asia Pacific Reports: Chinese Domestic Auto Brands Gain Ground in Designing Appealing Cars Beijing Hyundai and Shanghai General Motors Each Receive Two Model-Level Awards; Land Rover Ranks Highest among Nameplates SHANGHAI: 29 November 2013 — When it comes to the appeal of new vehicles, Chinese domestic auto brands have narrowed the gap with international brands to its slimmest level since 2003, according to the J.D. Power Asia Pacific 2013 China Automotive Performance, Execution and Layout (APEAL) StudySM released today. Now in its 11th year, the study examines how gratifying a new vehicle is to own and drive, based on owner evaluations during the first two to six months of ownership. The study examines 82 attributes across 10 vehicle performance categories: vehicle exterior; vehicle interior; storage and space; audio/ entertainment/ navigation; seats; HVAC; driving dynamics; engine/ transmission; visibility and driving safety; and fuel economy. The overall APEAL score among Chinese domestic brands averages 772 points (on a 1,000-point scale), compared with 816 among international brands. The 44-point gap between domestic and international brands is the smallest in the history of the study and down from a 58-point gap in 2012. Collectively, Korean brands achieve the highest average APEAL score by country of origin, with an average score of 838 points. European brands average 823 points, followed by U.S. (805) and Japanese (800) brands. Chinese brands average 32 points below industry average, an improvement from 2012 when they were 41 points below industry average. The overall new-vehicle APEAL score in 2013 averages 804 points in 2013, decreasing by 18 points from 2012. -

Hyundai/Kia Key Teaching

HiCOM key teaching manual www.obdtester.com/hicom Hyundai/Kia key teaching Table of Contens 1.SMARTRA introduction....................................................................................................................2 PIN Codes........................................................................................................................................2 2.Supported vehicles.............................................................................................................................3 3.Mechanical keys with RFID chip......................................................................................................5 Teaching...........................................................................................................................................5 4.Smartkey ...........................................................................................................................................7 Teaching...........................................................................................................................................7 5.Key information.................................................................................................................................8 6.Login..................................................................................................................................................8 7.Password Teaching/Changing............................................................................................................9 8.Neutral -

Customer Satisfaction Is a Term Frequently Used in Marketing. It Is a Measure of How Products and Services Supplied by a Company Meet Or Surpass Customer Expectation

Customer satisfaction is a term frequently used in marketing. It is a measure of how products and services supplied by a company meet or surpass customer expectation. Customer satisfaction is defined as "the number of customers, or percentage of total customers, whose reported experience with a firm, its products, or its services (ratings) exceeds specified satisfaction goals."[1] In a survey of nearly 200 senior marketing managers, 71 percent responded that they found a customer satisfaction metric very useful in managing and monitoring their businesses.[1] It is seen as a key performance indicator within business and is often part of a Balanced Scorecard. In a competitive marketplace where businesses compete for customers, customer satisfaction is seen as a key differentiator and increasingly has become a key element of business strategy.[2] "Within organizations, customer satisfaction ratings can have powerful effects. They focus employees on the importance of fulfilling customers' expectations. Furthermore, when these ratings dip, they warn of problems that can affect sales and profitability.... These metrics quantify an important dynamic. When a brand has loyal customers, it gains positive word-of-mouth marketing, which is both free and highly effective."[1] Therefore, it is essential for businesses to effectively manage customer satisfaction. To be able do this, firms need reliable and representative measures of satisfaction. "In researching satisfaction, firms generally ask customers whether their product or service has met or exceeded expectations. Thus, expectations are a key factor behind satisfaction. When customers have high expectations and the reality falls short, they will be disappointed and will likely rate their experience as less than satisfying. -

Hyundai Is First to Launch Series Production of ZeroEmissions Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicle

Hyundai Motor America 10550 Talbert Ave, Fountain Valley, CA 92708 MEDIA WEBSITE: HyundaiNews.com CORPORATE WEBSITE: HyundaiUSA.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE HYUNDAI IS FIRST TO LAUNCH SERIES PRODUCTION OF ZEROEMISSIONS HYDROGEN FUEL CELL VEHICLE Andreas Brozat James Parsons Head of PR & BTL Head of PR & BTL +49 69 271 472 412 +49 69 271472 402 abrozat@hyundaieurope.com jparsons@hyundaieurope.com ID: 37442 Up to 1,000 ix35 Fuel Cells on the road through 2015 Cuttingedge proof of Hyundai’s commitment to ecofriendly mobility Public, private fleets targeted Offenbach, 27 September 2012 Hyundai Motor Co. announced today that it will begin series production of its hydrogen ix35 Fuel Cell vehicle for public and private lease by the end of 2012, becoming the first global automaker to begin commercial rollout of zeroemissions vehicles. In December 2012, Hyundai will begin production of the ix35 Fuel Cell at its Ulsan manufacturing facility in Korea, with a target of building up to 1,000 vehicles by 2015. Hyundai has already signed contracts with cities in Denmark and Sweden to lease the ix35 Fuel Cell to municipal fleets. Beyond 2015, Hyundai plans limited mass production of the ix35 Fuel Cell, with a goal of 10,000 units. “The ix35 Fuel Cell is the pinnacle of Hyundai’s advanced engineering and our most powerful commitment to be the industry leader in ecofriendly mobility,” said Vice Chairman Woong Chul Yang, head of Hyundai R&D. “Zeroemissions cars are no longer a dream. Our ix35 Fuel Cell vehicle is here today, and ready for commercial use.” Built with proprietary technology, Hyundai’s ix35 Fuel Cell is powered by hydrogen. -

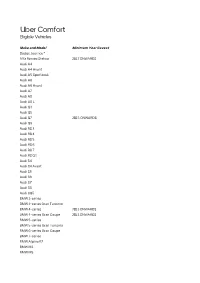

Uber Comfort Vehicle List

Uber Comfort Eligible Vehicles Make and Model Minimum Year Caveat Dodge Journey * Alfa Romeo Stelvio 2017 ONWARDS Audi A4 Audi A4 Avant Audi A5 Sportback Audi A6 Audi A6 Avant Audi A7 Audi A8 Audi A8 L Audi Q3 Audi Q5 Audi Q7 2015 ONWARDS Audi Q9 Audi RS 3 Audi RS 4 Audi RS 5 Audi RS 6 Audi RS 7 Audi RS Q3 Audi S4 Audi S4 Avant Audi S5 Audi S6 Audi S7 Audi S8 Audi SQ5 BMW 3-series BMW 3-series Gran Turismo BMW 4-series 2013 ONWARDS BMW 4-series Gran Coupe 2013 ONWARDS BMW 5-series BMW 5-series Gran Turismo BMW 6-series Gran Coupe BMW 7-series BMW Alpina B7 BMW M3 BMW M5 BMW M6 Gran Coupe BMW X1 BMW X3 BMW X4 2018 ONWARDS BMW X5 2013 ONWARDS BMW X6 Cadillac Escalade * Chrysler 200 * Chrysler 300 Chrysler PT Cruiser * Chrysler Sebring * Chrysler Voyager * Citroen C4 Citroen C4 Picasso Citroen C5 Citroen Grand Picasso Dodge Nitro * Fiat Freemont * Ford Escape 2017 ONWARDS Ford Everest 2015 ONWARDS Ford Fairlane * Ford Falcon Ford Fusion * Ford Kuga Ford Mondeo Ford Territory Genesis G80 2019 ONWARDS Genesis G90 * Great Wall X200 * Great Wall X240 * Haval H9 * Holden Berlina Holden Calais Holden Caprice Holden Captiva Holden Clubsport Holden Colorado 7 Holden Commodore Holden Equinox 2017 ONWARDS Holden GTS Holden Grange Holden Malibu 2013 ONWARDS Holden SV6 Holden Senator Holden Statesman Holden Trailblazer 2016 ONWARDS Holden Trax 2013 ONWARDS Honda Accord Honda CR-V Honda Freed * Honda Odyssey 2014 ONWARDS Hummer H3 * Hyundai Genesis 2014 ONWARDS Hyundai Santa Fe Hyundai Sonata 2015 ONWARDS Hyundai Starex * Hyundai Tucson 2015 ONWARDS