Topic 03 Overview of Plant Taxa Lecture Reading: 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

California's Native Ferns

CALIFORNIA’S NATIVE FERNS A survey of our most common ferns and fern relatives Native ferns come in many sizes and live in many habitats • Besides living in shady woodlands and forests, ferns occur in ponds, by streams, in vernal pools, in rock outcrops, and even in desert mountains • Ferns are identified by producing fiddleheads, the new coiled up fronds, in spring, and • Spring from underground stems called rhizomes, and • Produce spores on the backside of fronds in spore sacs, arranged in clusters called sori (singular sorus) Although ferns belong to families just like other plants, the families are often difficult to identify • Families include the brake-fern family (Pteridaceae), the polypody family (Polypodiaceae), the wood fern family (Dryopteridaceae), the blechnum fern family (Blechnaceae), and several others • We’ll study ferns according to their habitat, starting with species that live in shaded places, then moving on to rock ferns, and finally water ferns Ferns from moist shade such as redwood forests are sometimes evergreen, but also often winter dormant. Here you see the evergreen sword fern Polystichum munitum Note that sword fern has once-divided fronds. Other features include swordlike pinnae and round sori Sword fern forms a handsome coarse ground cover under redwoods and other coastal conifers A sword fern relative, Dudley’s shield fern (Polystichum dudleyi) differs by having twice-divided pinnae. Details of the sori are similar to sword fern Deer fern, Blechnum spicant, is a smaller fern than sword fern, living in constantly moist habitats Deer fern is identified by having separate and different looking sterile fronds and fertile fronds as seen in the previous image. -

Variation in Sex Expression in Canada Yew (Taxus Canadensis) Author(S): Taber D

Variation in Sex Expression in Canada Yew (Taxus canadensis) Author(s): Taber D. Allison Source: American Journal of Botany, Vol. 78, No. 4 (Apr., 1991), pp. 569-578 Published by: Botanical Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2445266 . Accessed: 23/08/2011 15:56 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Botanical Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Journal of Botany. http://www.jstor.org AmericanJournal of Botany 78(4): 569-578. 1991. VARIATION IN SEX EXPRESSION IN CANADA YEW (TAXUS CANADENSIS)1 TABER D. ALLISON2 JamesFord Bell Museumof Natural History and Departmentof Ecology and BehavioralBiology, Universityof Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55455 Sex expressionwas measuredin severalCanada yew (Taxus canadensisMarsh.) populations of theApostle Islands of Wisconsinand southeasternMinnesota to determinethe extent of variationwithin and among populations. Sex expression was recorded qualitatively (monoecious, male,or female) and quantitatively (by male to female strobilus ratios or standardized phenotypic gender).No discernibletrends in differencesin sex expressionamong populations or habitats wererecorded. Trends in sexexpression of individuals within populations were complex. Small yewstended to be maleor, if monoecious, had female-biasedstrobilus ratios. -

Information and Care Instructions Mother Fern

Information and Care Instructions Mother Fern Quick Reference Botanical Name - Asplenium bulbiferum Detailed Care Exposure - Shade to bright, indirect Your Mother Fern was grown in a plastic pot. Depending on the item, it may then have been Indoor Placement - Bright location but not in direct afternoon sun transplanted into a decorative pot before sale or simply “dropped” into a container while still in the USDA Hardiness - Zone 10a to 11 plastic pot. Inside Temperature - 50-70˚F WATERING Min Outside Temperature - 30˚F 1. Let the top of the soil dry out slightly before Plant Type - Evergreen Fern watering; check frequently, especially if kept in a hot, dry spot. Mother Ferns like to be kept evenly moist, Watering - Allow soil to dry out slightly before watering. Do not allow but not soggy. the pot to sit in standing water for more than a few minutes 2. When watering, use the recommended amount of water for your pot size (See Quick Reference Guide) Water Amount Used - 4” Pot = 1/3 cup of water poured directly on the soil. In order not to damage 6 1/2” Pot = 1 1/4 cups of water your furniture, countertop or floor, place your Mother Fertilizing - Fertilize monthly Fern in a saucer, bowl or sink when watering. Allow the water to drain for 5 minutes. Do not allow the soil to sit in water for any more than 5 minutes or damage to the roots may occur. Avoid continuous use of softened water as the sodium in it can build up to damaging levels in the soil. -

Earliest Record of Megaphylls and Leafy Structures, and Their Initial Diversification

Review Geology August 2013 Vol.58 No.23: 27842793 doi: 10.1007/s11434-013-5799-x Earliest record of megaphylls and leafy structures, and their initial diversification HAO ShouGang* & XUE JinZhuang Key Laboratory of Orogenic Belts and Crustal Evolution, School of Earth and Space Sciences, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China Received January 14, 2013; accepted February 26, 2013; published online April 10, 2013 Evolutionary changes in the structure of leaves have had far-reaching effects on the anatomy and physiology of vascular plants, resulting in morphological diversity and species expansion. People have long been interested in the question of the nature of the morphology of early leaves and how they were attained. At least five lineages of euphyllophytes can be recognized among the Early Devonian fossil plants (Pragian age, ca. 410 Ma ago) of South China. Their different leaf precursors or “branch-leaf com- plexes” are believed to foreshadow true megaphylls with different venation patterns and configurations, indicating that multiple origins of megaphylls had occurred by the Early Devonian, much earlier than has previously been recognized. In addition to megaphylls in euphyllophytes, the laminate leaf-like appendages (sporophylls or bracts) occurred independently in several dis- tantly related Early Devonian plant lineages, probably as a response to ecological factors such as high atmospheric CO2 concen- trations. This is a typical example of convergent evolution in early plants. Early Devonian, euphyllophyte, megaphyll, leaf-like appendage, branch-leaf complex Citation: Hao S G, Xue J Z. Earliest record of megaphylls and leafy structures, and their initial diversification. Chin Sci Bull, 2013, 58: 27842793, doi: 10.1007/s11434- 013-5799-x The origin and evolution of leaves in vascular plants was phology and evolutionary diversification of early leaves of one of the most important evolutionary events affecting the basal euphyllophytes remain enigmatic. -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

Seedless Plants Key Concept Seedless Plants Do Not Produce Seeds 2 but Are Well Adapted for Reproduction and Survival

Seedless Plants Key Concept Seedless plants do not produce seeds 2 but are well adapted for reproduction and survival. What You Will Learn When you think of plants, you probably think of plants, • Nonvascular plants do not have such as trees and flowers, that make seeds. But two groups of specialized vascular tissues. plants don’t make seeds. The two groups of seedless plants are • Seedless vascular plants have specialized vascular tissues. nonvascular plants and seedless vascular plants. • Seedless plants reproduce sexually and asexually, but they need water Nonvascular Plants to reproduce. Mosses, liverworts, and hornworts do not have vascular • Seedless plants have two stages tissue to transport water and nutrients. Each cell of the plant in their life cycle. must get water from the environment or from a nearby cell. So, Why It Matters nonvascular plants usually live in places that are damp. Also, Seedless plants play many roles in nonvascular plants are small. They grow on soil, the bark of the environment, including helping to form soil and preventing erosion. trees, and rocks. Mosses, liverworts, and hornworts don’t have true stems, roots, or leaves. They do, however, have structures Vocabulary that carry out the activities of stems, roots, and leaves. • rhizoid • rhizome Mosses Large groups of mosses cover soil or rocks with a mat of Graphic Organizer In your Science tiny green plants. Mosses have leafy stalks and rhizoids. A Journal, create a Venn Diagram that rhizoid is a rootlike structure that holds nonvascular plants in compares vascular plants and nonvas- place. Rhizoids help the plants get water and nutrients. -

X. the Conifers and Ginkgo

X. The Conifers and Ginkgo Now we turn our attention to the Coniferales, another great assemblage of seed plants. First let's compare the conifers with the cycads: Cycads Conifers few apical meristems per plant many apical meristems per plant leaves pinnately divided leaves undivided wood manoxylic wood pycnoxylic seeds borne on megaphylls seeds borne on stems We should also remember that these two groups have a lot in common. To begin with, they are both groups of woody seed plants. They are united by a small set of derived features: 1) the basic structure of the stele (a eustele or a sympodium, two words for the same thing) and no leaf gaps 2) the design of the apical meristem (many initials, subtended by a slowly dividing group of cells called the central mother zone) 3) the design of the tracheids (circular-bordered pits with a torus) We have three new seed plant orders to examine this week: A. Cordaitales This is yet another plant group from the coal forest. (Find it on the Peabody mural!) The best-known genus, Cordaites, is a tree with pycnoxylic wood bearing leaves up to about a foot and a half long and four inches wide. In addition, these trees bore sporangia (micro- and mega-) in strobili in the axils of these big leaves. The megasporangia were enclosed in ovules. Look at fossils of leaves and pollen-bearing shoots of Cordaites. The large, many-veined megaphylls are ancestral to modern pine needles; the shoots are ancestral to pollen-bearing strobili of modern conifers. 67 B. -

Evolution of Land Plants P

Chapter 4. The evolutionary classification of land plants The evolutionary classification of land plants Land plants evolved from a group of green algae, possibly as early as 500–600 million years ago. Their closest living relatives in the algal realm are a group of freshwater algae known as stoneworts or Charophyta. According to the fossil record, the charophytes' growth form has changed little since the divergence of lineages, so we know that early land plants evolved from a branched, filamentous alga dwelling in shallow fresh water, perhaps at the edge of seasonally-desiccating pools. The biggest challenge that early land plants had to face ca. 500 million years ago was surviving in dry, non-submerged environments. Algae extract nutrients and light from the water that surrounds them. Those few algae that anchor themselves to the bottom of the waterbody do so to prevent being carried away by currents, but do not extract resources from the underlying substrate. Nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, together with CO2 and sunlight, are all taken by the algae from the surrounding waters. Land plants, in contrast, must extract nutrients from the ground and capture CO2 and sunlight from the atmosphere. The first terrestrial plants were very similar to modern mosses and liverworts, in a group called Bryophytes (from Greek bryos=moss, and phyton=plants; hence “moss-like plants”). They possessed little root-like hairs called rhizoids, which collected nutrients from the ground. Like their algal ancestors, they could not withstand prolonged desiccation and restricted their life cycle to shaded, damp habitats, or, in some cases, evolved the ability to completely dry-out, putting their metabolism on hold and reviving when more water arrived, as in the modern “resurrection plants” (Selaginella). -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

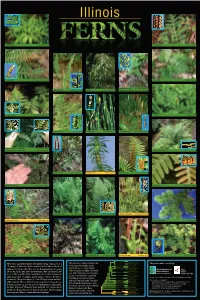

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Havens for Wildlife

)"7&/4'038*-%-*'& 4FDUJPO# .PTTFT -JWFSXPSUTBOE'FSOT This sheet explains what mosses, liverworts and Liverworts ferns are, where they occur and guidelines on how Liverworts are similar to to care for them in a burial ground. mosses but tend to be The earliest land plants were related to ferns and leafy and are less common. mosses. They started life growing on the edge of lakes Liverworts are mostly found and rivers 400 million years ago. Today most ferns, in woodland and by streams mosses and liverworts still need to grow in moist or rivers but can also be found places. on shady stones and damp soil in burial grounds. They are With our damp climate many burial sites prove ideal for strange, distinctive looking ferns, mosses and liverworts, particularly in the western plants and worth looking at areas of Britain and Ireland. closely or photographing their Adder’s-tongue Fern intricate shapes and subtle colours. MOSSES AND LIVERWORTS Mosses and liverworts are known as FERNS ‘bryophytes’. They are small, green plants *OUIFDPPM XFUDMJNBUFPGUIF6,UIFSFBSFUZQFTPG which do not have !owers or seeds but fern. Look out for ferns on west or north facing walls produce spores instead. There are over in particular. The shady areas of burial grounds, and 1000 di"erent species of bryophyte in under trees, where grass cutters don’t reach, will also UIF6,BOEUIFZUFOEUPCFGPVOEJO be places where ferns can !ourish undisturbed. sheltered, damp places as most of them cannot survive drying out. Few mosses An amazing fact about ferns is that once established PSMJWFSXPSUTIBWF&OHMJTIOBNFTBOEB they can survive in quite dry places, such as walls. -

Seasonal Growth of the Female Strobilus in Pinus Radiata

No. 1 15 SEASONAL GROWTH OF THE FEMALE STROBILUS IN PINUS RADIATA G. B. SWEET and M. P. BOLLMANN Forest Research Institute, New Zealand Forest Service, Rotorua (Received for publication 12 November, 1970) ABSTRACT Growth of female strobili of Pinus radiata D. Don from central North Island of New Zealand is described and illustrated with photographs. The two-and-a-half year period from strobilus emergence until cone maturity comprises a seasonal period of growth in which pollination occurs, a second period of seasonal growth in which fertilisation occurs, and finally a period of cone maturation. The periods of rapid growth do not appear to result directly from either pollination or fertilisation, and the seasonal growth periods have some similarity to those of vegetative growth. The time taken to reach cone maturity in P. radiata (a closed-cone pine) is six months longer than that frequently described for other species of Pinus. INTRODUCTION The general pattern of female strobilus development in Pinus is well documented (e.g., Ferguson, 1904; Stanley, 1958; Sarvas, 1962). Broadly, a total period of two-and- a-half years is involved, leading through from strobilus determination one summer, to anthesis the following spring, to fertilisation late in the subsequent spring and finally to maturation the succeeding autumn. Seed production in Pinus radiata D. Don apparently follows within general limits the typical pattern for Pinus, but few details have been published either of its strobilus or its ovule development. As part of a comprehensive study of the processes leading to seed production in this species, material was collected in 1968 and 1969 to enable details of strobilus development to be determined. -

Late Devonian Spermatophyte Diversity and Paleoecology at Red Hill, North-Central Pennsylvania, U.S.A. Walter L

West Chester University Digital Commons @ West Chester University Geology & Astronomy Faculty Publications Geology & Astronomy 2010 Late Devonian spermatophyte diversity and paleoecology at Red Hill, north-central Pennsylvania, U.S.A. Walter L. Cressler III West Chester University, [email protected] Cyrille Prestianni Ben A. LePage Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcupa.edu/geol_facpub Part of the Geology Commons, Paleobiology Commons, and the Paleontology Commons Recommended Citation Cressler III, W.L., Prestianni, C., and LePage, B.A. 2010. Late Devonian spermatophyte diversity and paleoecology at Red Hill, north- central Pennsylvania, U.S.A. International Journal of Coal Geology 83, 91-102. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Geology & Astronomy at Digital Commons @ West Chester University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Geology & Astronomy Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ West Chester University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE IN PRESS COGEL-01655; No of Pages 12 International Journal of Coal Geology xxx (2009) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Coal Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijcoalgeo Late Devonian spermatophyte diversity and paleoecology at Red Hill, north-central Pennsylvania, USA Walter L. Cressler III a,⁎, Cyrille Prestianni b, Ben A. LePage c a Francis Harvey Green Library, 29 West Rosedale Avenue, West Chester University, West Chester, PA, 19383, USA b Université de Liège, Boulevard du Rectorat B18, Liège 4000 Belgium c The Academy of Natural Sciences, 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, PA, 19103 and PECO Energy Company, 2301 Market Avenue, S9-1, Philadelphia, PA 19103, USA article info abstract Article history: Early spermatophytes have been discovered at Red Hill, a Late Devonian (Famennian) fossil locality in north- Received 9 January 2009 central Pennsylvania, USA.