ARSC Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VOCAL 78 Rpm Discs Minimum Bid As Indicated Per Item

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs Minimum bid as indicated per item. Listings “Just about 1-2” should be considered as mint and “Cons. 2” with just the slightest marks. For collectors searching top copies, you’ve come to the right place! The further we get from the time of production (in many cases now 100 years or more), the more difficult it is to find such excellent extant pressings. Some are actually from mint dealer stocks and others the result of having improved copies via dozens of collections purchased over the past fifty years. * * * For those looking for the best sound via modern reproduction, those items marked “late” are usually of high quality shellac, pressed in the 1950-55 period. A number of items in this particular catalogue are excellent pressings from that era. * * * Please keep in mind that the minimum bids are in U.S. Dollars, a benefit to most collectors. * * * “Text label on verso.” For a brief period (1912-14), Victor pressed silver-on-black labels on the reverse sides of some of their single-faced recordings, usually with a translation of the text or similarly related comments. BESSIE ABOTT [s]. Riverdale, NY, 1878-New York, 1919. Following the death of her father which left her family penniless, Bessie and her sister Jessie (born Pickens) formed a vaudeville sister vocal act, accompanying themselves on banjo and guitar. Upon the recommendation of Jean de Reszke, who heard them by chance, Bessie began operatic training with Frida Ashforth. She subsequently studied with de Reszke him- self and appeared with him at the Paris Opéra, making her debut as Gounod’s Juliette. -

Bellini's Norma

Bellini’s Norma - A discographical survey by Ralph Moore There are around 130 recordings of Norma in the catalogue of which only ten were made in the studio. The penultimate version of those was made as long as thirty-five years ago, then, after a long gap, Cecilia Bartoli made a new recording between 2011 and 2013 which is really hors concours for reasons which I elaborate in my review below. The comparative scarcity of studio accounts is partially explained by the difficulty of casting the eponymous role, which epitomises bel canto style yet also lends itself to verismo interpretation, requiring a vocalist of supreme ability and versatility. Its challenges have thus been essayed by the greatest sopranos in history, beginning with Giuditta Pasta, who created the role of Norma in 1831. Subsequent famous exponents include Maria Malibran, Jenny Lind and Lilli Lehmann in the nineteenth century, through to Claudia Muzio, Rosa Ponselle and Gina Cigna in the first part of the twentieth. Maria Callas, then Joan Sutherland, dominated the role post-war; both performed it frequently and each made two bench-mark studio recordings. Callas in particular is to this day identified with Norma alongside Tosca; she performed it on stage over eighty times and her interpretation casts a long shadow over. Artists since, such as Gencer, Caballé, Scotto, Sills, and, more recently, Sondra Radvanovsky have had success with it, but none has really challenged the supremacy of Callas and Sutherland. Now that the age of expensive studio opera recordings is largely over in favour of recording live or concert performances, and given that there seemed to be little commercial or artistic rationale for producing another recording to challenge those already in the catalogue, the appearance of the new Bartoli recording was a surprise, but it sought to justify its existence via the claim that it authentically reinstates the integrity of Bellini’s original concept in matters such as voice categories, ornamentation and instrumentation. -

La Gioconda (Review) William Ashbrook

La Gioconda (review) William Ashbrook The Opera Quarterly, Volume 18, Number 1, Winter 2002, pp. 128-129 (Review) Published by Oxford University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/25455 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] 128 recordings La Gioconda. Amilcare Ponchielli La Gioconda: Giannina Arangi-Lombardi Isepo/Singer: Giuseppe Nessi Laura: Ebe Stignani Zuane/Singer: Aristide Baracchi La Cieca: Camilla Rota Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala, Milan Enzo Grimaldo: Alessandro Granda Lorenzo Molajoli, conductor Barnaba: Gaetano Viviani Naxos Historical 8.110112–14 (3 CDs) Alvise Badoero: Corrado Zambelli This is the complete Gioconda from 1931, recorded by Italian Columbia, but never issued in the United States during the 78 r.p.m. era. Here it is, vividly remastered by Ward Marston, with bonus tracks consisting of eight arias and two duets featuring the soprano Giannina Arangi-Lombardi, whom Max de Schauensee always referred to as “the Ponselle of Italy.” I have a special aVection for La Gioconda, as it was my first opera, seen when I was seven. Three things made an unforgettable impression on me. Hearing big voices live had quite an impact, since before then I had heard opera only on acoustic records (I still think that Julia Claussen, the Laura of that occasion, could sing louder than anyone I have heard since); although the plot made no sense to me, the Dance of the Hours seemed perfectly logical; and I got cold chills from the moment the big ensemble was launched at the end of act 3. -

Staged Treasures

Italian opera. Staged treasures. Gaetano Donizetti, Giuseppe Verdi, Giacomo Puccini and Gioacchino Rossini © HNH International Ltd CATALOGUE # COMPOSER TITLE FEATURED ARTISTS FORMAT UPC Naxos Itxaro Mentxaka, Sondra Radvanovsky, Silvia Vázquez, Soprano / 2.110270 Arturo Chacon-Cruz, Plácido Domingo, Tenor / Roberto Accurso, DVD ALFANO, Franco Carmelo Corrado Caruso, Rodney Gilfry, Baritone / Juan Jose 7 47313 52705 2 Cyrano de Bergerac (1875–1954) Navarro Bass-baritone / Javier Franco, Nahuel di Pierro, Miguel Sola, Bass / Valencia Regional Government Choir / NBD0005 Valencian Community Orchestra / Patrick Fournillier Blu-ray 7 30099 00056 7 Silvia Dalla Benetta, Soprano / Maxim Mironov, Gheorghe Vlad, Tenor / Luca Dall’Amico, Zong Shi, Bass / Vittorio Prato, Baritone / 8.660417-18 Bianca e Gernando 2 Discs Marina Viotti, Mar Campo, Mezzo-soprano / Poznan Camerata Bach 7 30099 04177 5 Choir / Virtuosi Brunensis / Antonino Fogliani 8.550605 Favourite Soprano Arias Luba Orgonášová, Soprano / Slovak RSO / Will Humburg Disc 0 730099 560528 Maria Callas, Rina Cavallari, Gina Cigna, Rosa Ponselle, Soprano / Irene Minghini-Cattaneo, Ebe Stignani, Mezzo-soprano / Marion Telva, Contralto / Giovanni Breviario, Paolo Caroli, Mario Filippeschi, Francesco Merli, Tenor / Tancredi Pasero, 8.110325-27 Norma [3 Discs] 3 Discs Ezio Pinza, Nicola Rossi-Lemeni, Bass / Italian Broadcasting Authority Chorus and Orchestra, Turin / Milan La Scala Chorus and 0 636943 132524 Orchestra / New York Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra / BELLINI, Vincenzo Vittorio -

Arena Di Verona “Turandot” Con Il Sostegno Del Comune Di Padova

Comune di Padova Centro Socio-Culturale Età D’Oro con il sostegno del Comune di Padova Via J. Da Ponte 7 35134 Padova Quartiere 2 Nord Tel. 0498649310 mail [email protected] aperto il pomeriggio dalle 15.00 alle 19.00 Giovedì 5 luglio 2018 Arena di Verona “Turandot” Con il sostegno del Comune di Padova La Turandot è un'opera in 3 atti e 5 quadri, su libretto di Giuseppe Adami e Renato Simoni, lasciata incompiuta da Giacomo Puccini e successivamente completata da Franco Alfano, uno dei suoi allievi. Fu rappresentata per la prima volta il 25 aprile 1926 al Teatro alla Scala di Milano, con Rosa Raisa, Francesco Dominici, Miguel Fleta, Maria Zamboni, Giacomo Rimini e Giuseppe Nessi sotto la direzione di Arturo Toscanini, il quale interruppe la rappresentazione a metà del terzo atto, due battute dopo il verso «Dormi, oblia, Liù, poesia!», ovvero dopo l'ultima pagina completata dall'autore, dichiarando al pubblico: «Qui termina la rappresentazione perché a questo punto il Maestro è morto.» La sera successiva, sempre sotto la direzione di Toscanini, l'opera fu rappresentata nella sua completezza, includendo anche il finale di Alfano. Nel dicembre del 1923 il Maestro completò tutta la partitura fino alla morte di Liù, cioè fino all'inizio del duetto cruciale. Di questo finale egli stese solo una versione in abbozzo discontinuo. Puccini morì a Bruxelles il 29 novembre 1924, lasciando le bozze del duetto finale così come le aveva scritte il dicembre precedente. L'incompiutezza dell'opera è oggetto di discussione tra gli studiosi. C'è chi sostiene che Turandot rimase incompiuta non a causa della morte dell'autore, bensì per l'incapacità, o piuttosto l’impossibilità da parte del Maestro di risolvere il nodo cruciale del dramma: la trasformazione della principessa Turandot gelida e sanguinaria, in una donna innamorata. -

Miguel Fleta (1897-1938) Y Turandot (1926). Una Puesta En Escena Oriental

MIGUEL FLETA (1897-1938) Y TURANDOT (1926). UNA PUESTA EN ESCENA ORIENTAL Miguel Fleta (1897-1938) & Turandot (1926): An Oriental Mise-en-scène María Pilar Araguás Biescas* María Asunción Araguás Biescas** Universidad de Zaragoza Resumen La ópera inacabada Turandot del compositor italiano Giacomo Puccini (1858- 1924) fue una de las óperas japonistas cuyo argumento se desarrolla en China y cuya creación se enmarca en un período de moda e interés por el país del Sol Na- ciente. Estrenada en 1926 en La Scala de Milán narra la historia del príncipe Calaf que se enamora de la fría princesa Turandot. En su estreno participó el tenor ara- gonés Miguel Fleta (1897-1938) en el papel de Calaf. Palabras clave: Miguel Fleta, Turandot, Giacomo Puccini, ópera, japonismo Abstract Turandot is an opera by Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) and it was an example of a Japonisme on music. The story, set in China, involves prince Calaf who falls in love with the cold princess Turandot. The opera was unfinished at the time of Puccini’s death in 1924. The first performance was held at the Teatro alla Scala in Milan. Miguel Fleta had the honour of creating the role of Calaf. Key words: Miguel Fleta, Turandot, Giacomo Puccini, opera, japonisme. * Doctora en Historia del Arte en la Universidad de Zaragoza. Investigadora del proyec- to I+D Coleccionismo y coleccionistas de arte japonés en España. Correo electrónico: [email protected]. Fecha de recepción del artículo: 1 de septiembre de 2011. Fecha de aceptación: 3 de octubre de 2011. ** Licenciada en Medicina y Cirugía por la Universidad de Zaragoza y estudios superiores de música en el Conservatorio de Sabiñánigo. -

Genève L'autographe

l’autographe Genève l'autographe L’Autographe S.A. 24 rue du Cendrier, CH - 1201, Genève +41 22 510 50 59 (mobile) +41 22 523 58 88 (bureau) web: www.lautographe.com mail: [email protected] All autographs are offered subject to prior sale. Prices are quoted in US DOLLARS, SWISS FRANCS and EUROS and do not include postage. All overseas shipment will be sent by air. Orders above € 1000 benefits of free shipping. We accept payments via bank transfer, PayPal, and all major credit cards. We do not accept bank checks. Images not reproduced will be provided on request Postfinance CCP 61-374302-1 3 rue du Vieux-Collège CH-1204, Genève IBAN: EUR: CH94 0900 0000 9175 1379 1 CHF: CH94 0900 0000 6137 4302 1 SWIFT/BIC: POFICHBEXXX paypal.me/lautographe The costs of shipping and insurance are additional. Domestic orders are customarily shipped via La Poste. Foreign orders are shipped with La Poste and Federal Express on request. Great opera singers p. 4 Dance and Ballet p. 33 Great opera singers 1. Licia Albanese (Bari, 1909 - Manhattan, 2014) Photograph with autograph signature of the Italian soprano as Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. (8 x 10 inch. ). $ 35/ Fr. 30/ € 28 2. Lucine Amara (Hartford, 1924) Photographic portrait of the Metropolitan Opera's American soprano as Liu in Puccini’s Turandot (1926).(8 x 10 inch.). $ 35/ Fr. 30/ € 28 3. Vittorio Arimondi (Saluzzo, 1861 - Chicago, 1928) Photographic portrait with autograph signature of the Italian bass who created the role of Pistola in Verdi’s Falstaff (1893). $ 80/ Fr. -

Verdi's La Forza Del Destino

Verdi’s La forza del destino - A survey of the studio and selected live recordings by Ralph Moore Despite its musical quality, variety and sophistication, La forza del destino is something of an Ugly Duckling among Verdi’s mature works, and it is for that reason that I did not survey it when I previously covered most of Verdi’s major and most popular operas. It suffers from a sprawling structure whereby succeeding scenes can seem disjointed, some peculiar motivation, an excess of disguise, an uncertain tone resulting from an uneasy admixture of the tragic and the would-be comical, and the presence of two characters with whom, for different reasons, it is difficult to empathise. Don Carlo suffers from a pathological obsession with revenge resulting in his stabbing his own sister as an “honour killing”; his implacable bloodlust is both bizarre and deeply repugnant, while Preziosilla must be one of the most vapid and irritating cheerleaders in opera. “Rataplan, rataplan” – rum-ti-tum on the drum, indeed; it takes a special singer to transcend the banality of her music but it can be done. Although it is just about possible to argue that guilt and shame are at the root of their behaviour, it is mostly inexplicable to modern audiences that Alvaro and Leonora separate after her father’s accidental death and never again try to reunite until they meet again by chance – or fate - in the last scene set five years later. Verdi attempts to lighten the relentlessly grim mood by the inclusion of a supposedly comic character in Fra Melitone who often isn’t very funny – and what is the point of Trabuco, a superfluous peddler? Finally, what the heck is an Incan prince doing in Seville, anyway? While fully aware of its failings, I have returned to La forza del destino because it contains some marvellous music and the kinds of emotional turmoil and dramatic confrontation which lie at the heart of opera. -

18.5 Vocal 78S. Sagi-Barba -Zohsel, Pp 135-170

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs EMILIO SAGI-BARBA [b]. See also: MIGUEL FLETA [t], LUISA VELA [s] 1824. 10” Blue Victor 45284 [17579u/18709u]. NAZARETH [VILLANCICO] (Francisco Titto) / PLEGARIA A LA SANTISSIMA VIRGEN DEL PILAR (F. Agüeral). One harm- less lt., small discoloration patch side two, otherwise just about 1-2. $15.00. 3075. 12” Blue Victor 55143 (74389/74350) [02898½v/492ac]. EL CANTO DEL PRESI- DARIO (Alvarez) / Á TUS OJOS (Fuster). Few lightest mks. Cons . 2. $15.00. MATHILDE SAIMAN [s] 2357. 12” Red acous. Eng. Columbia D14203 [LX 13/LX 8]. GISMONDA: La paix du cloï- tre (Février) / MADAMA BUTTERFLY: Sur la mer calmée (Puccini). Side one just about 1-2. Side two cons . 2. $15.00. GIUSEPPE SALA [t]. Kutsch-Riemens suggests a birthdate of around 1870. Sala appears to have been active particularly in comprimario roles through at least 1911. 1n 1910, Giovanni Martinelli, basically then unknown, replaced Sala in a 1910 Teatro dal Verme performance of the Verdi Requiem . Martinelli’s sucess that evening led to his operatic debut there three weeks later as Verdi’s Ernani. Sala, however, experienced success by participating in the Teatro dal Verme world premiere of Zandonai’s Conchita and the Teatro Costanzi Italian premiere of Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West , both in 1911. What became of him subsequently doesn’t seem to be known. 1199. 11” Brown Odeon 37351/37346 [Xm633/Xm577]. I PURITANI: A te o cara (Bel- lini)/ DORA DOMAR [s]. MARRIAGE OF FIGARO: Voi che sapete (Mozart). Side one cons. 2. Side two gen . 2. -

ARSC Journal

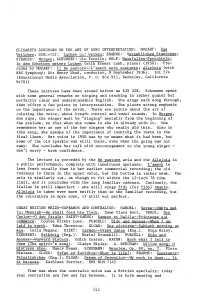

ELISABETH SCHU}~.NN ON THE ART OF SONG INTERPRETATION: MOZART: Das Veilchen; SCHLiF::rr: Lachen unc~ weinen; BRAHMS: Vergebliches Standchen; STRAUSS: Morgen; SCHUBERT: Die Forelle; WOLF: Mausfallen-Spruchlein; In dem Schetteil°meiner Locken (with Ernest Lush, piano) (1950). Pre ceded by MOZART: Il Re pastore--L'amero sero costante; Alleluia (with BBC Symphony; Sir Henry Wood, conductor, 8 September 1936). IGI 274 (Educational Media Association, P. 0. Box 921, Berkeley, California 94701) These lectures have been around before as EJS 328. Schumann opens with some general remarks on singing and teaching in rather quaint but perfectly clear and understandable English. She sings each song through, then offers a few points on interpretation. She places strong emphasis on the importance of the words. There are points about the art of coloring the voice, about breath control and vowel sounds. In Morgen, she says, the singer must be "singing" mentally from the beginning of the prelude, so that when she comes in she is already with it. One remembers her as one of the few singers who really did this. Also in this song, she speaks of the importance of counting the rests in the final lines. Her voice in 1950 was by no means what it had been, but some of the old sparkle was still there, even when the going was not easy. She concludes her talk with encouragement to the young singer - don't worry - have confidence. The lecture is preceded by the Re pastore aria and the Alleluia in a public performance, complete with tumultuous applause. L'amero is less fresh vocally than in her earlier commercial recording; the old radiance is there in the upper voice, but the bottom is rather weak. -

Copyright by Melody Marie Rich 2003

Copyright by Melody Marie Rich 2003 The Treatise Committee for Melody Marie Rich certifies that this is the approved version of the following treatise: Pietro Cimara (1887-1967): His Life, His Work, and Selected Songs Committee: _____________________________ Andrew Dell’Antonio, Supervisor _____________________________ Rose Taylor, Co-Supervisor _____________________________ Judith Jellison _____________________________ Leonard A. Johnson _____________________________ Karl Miller _____________________________ David A. Small Pietro Cimara (1887-1967): His Life, His Work, and Selected Songs by Melody Marie Rich, B.M., M.M. Treatise Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2003 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The journey to discovering Pietro Cimara began in 1996 at a summer workshop where upon first hearing “Ben venga amore,” I instantly knew that I had to have more of Cimara’s music. Since then, the momentum to see my research through to the finish would not have continued without the help of many wonderful people whom I wish to formally acknowledge. First, I must thank my supervisor, Dr. Andrew Dell’Antonio, Associate Professor of Musicology at the University of Texas at Austin. Without your gracious help and generous hours of assistance with Italian translation, this project would not have happened. Ringraziando di cuore, cordiali saluti! To my co-supervisor, Rose Taylor, your nurturing counsel and mounds of vocal wisdom have been a valuable part of my education and my saving grace on many occasions. Thank you for always making your door open to me. -

BOITO Mefistofele

110273-74 bk Boito US 02/06/2003 09:10 Page 12 Great Opera Recordings ADD 8.110273-74 Also available: 2 CDs BOITO Mefistofele Nazzareno de Angelis Mafalda Favero Antonio Melandri Giannina Arangi-Lombardi Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan 8.110117-18 Lorenzo Molajoli Recorded in 1931 8.110273-74 12 110273-74 bk Boito US 02/06/2003 09:10 Page 2 Ward Marston Great Opera Recordings In 1997 Ward Marston was nominated for the Best Historical Album Grammy Award for his production work on BMG’s Fritz Kreisler collection. According to the Chicago Tribune, Marston’s name is ‘synonymous with tender loving care to collectors of historical CDs’. Opera News calls his work ‘revelatory’, and Fanfare deems him Arrigo ‘miraculous’. In 1996 Ward Marston received the Gramophone award for Historical Vocal Recording of the Year, honouring his production and engineering work on Romophone’s complete recordings of Lucrezia Bori. He also BOITO served as re-recording engineer for the Franklin Mint’s Arturo Toscanini issue and BMG’s Sergey Rachmaninov (1842-1918) recordings, both winners of the Best Historical Album Grammy. Born blind in 1952, Ward Marston has amassed tens of thousands of opera classical records over the past four decades. Following a stint in radio while a student at Williams College, he became well-known as a reissue producer in 1979, when he restored the earliest known stereo recording made by the Bell Telephone Laboratories in 1932. Mefistofele In the past, Ward Marston has produced records for a number of major and specialist record companies.