Port Or Conversion? an Ontological Framework for Classifying Game Versions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THIS WEEK ...We Focus on Some More Titles That Have Made an Impression on Eurogamer Readers, and Reveal Why

Brought to you by Every week: The UK games market in less than ten minutes Issue 6: 14th - 20th July WELCOME ...to GamesRetail.biz, your weekly look at the key analysis, news and data sources for the retail sector, brought to you by GamesIndustry.biz and Eurogamer.net. THIS WEEK ...we focus on some more titles that have made an impression on Eurogamer readers, and reveal why. Plus - the highlights of an interview with Tony Hawk developer Robomodo, the latest news, charts, Eurogamer reader data, price comparisons, release dates, jobs and more! Popularity of Age of Conan - Hyborian Adventures in 2009 B AGE OF CONAN VS WII SPORTS RESORT #1 A This week we look at the Eurogamer buzz performance around two key products since the beginning of 2009. First up is the MMO Age of #10 Conan - a game which launched to great fanfare this time last year, but subsequently suffered from a lack of polish and endgame content. #100 Eurogamer.net Popularity (Ranked) Recently the developer, Funcom, attempted to reignite interest in the game by marketing the changes made in the build-up to its first anniversary - point A notes a big feature and #1000 Jul free trial key launch, while point B shows the Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jan '09 Age of Conan - Hyborian Adventures re-review which put the game right at the top of the pile earlier this month - whether that interest can be converted into subs is a different question, but the team has given itself a good Popularity of Wii Sports Resort in 2009 chance at least. -

Island People the Caribbean and the World 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ISLAND PEOPLE THE CARIBBEAN AND THE WORLD 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joshua Jelly-Schapiro | 9780385349765 | | | | | Island People The Caribbean and the World 1st edition PDF Book Archived from the original on October 30, Audio help More spoken articles. The oldest cathedral, monastery, and hospital in the Americas were established on the island, and the first university was chartered in Santo Domingo in From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Corn maize , beans , squash , tobacco , peanuts groundnuts , and peppers were also grown, and wild plants were gathered. Caryl-Sue, National Geographic Society. Email address. We scoured our vast selection of vintage books for the most beautiful dust jackets, and soon discovered that selecting just 30 was a nearly impossible task. First Separate Edition - The first appearance as a complete book or pamphlet of a work that has previously appeared as part of another book. Irma floods a beach in Marigot on September 6. Be on the lookout for your Britannica newsletter to get trusted stories delivered right to your inbox. Hurricane Irma devastated the US territory and other Caribbean islands in the region, leaving them exposed to new storms brewing in the Atlantic. By signing up, you agree to our Privacy Notice. Telltale Games. The limited historical records reveal a successive wave of Arawak immigrants moved from Orinoco Delta of South America towards the north, settling in the Caribbean Islands. Martin residents during a visit to the island on September Below is a set of some other glossary terms that booksellers use to describe different editions. It's a small island, 62 square miles, and its residents have a strong sense of belonging. -

Team Sega Issue #5

THE TEAM SEGA® NEWSLETTER • JAN. '89, No. 5 REGGIE JACKSON "BASEBALL! Hard-hitting ballpark action! |M ' 91 ON dlVd aovisod s n xnna From Thunder Blade to Monopoly, we've got a huge selection for the serious Sega fanatic. Think Sega, think Toys "R" Us. Not only are we the largest retailer of Sega systems, but our shelves are stocked with loads of game cartridges, available every day at incredibly low prices. Check us out^for yourself! THE WORLD'S BIGGEST TOY STORE Over 350 Toys "R" Us stores coast to coast, check your local directory for the store nearest you! We accept VISA, MASTERCARD, OPTIMA, AMERICAN EXPRESS and DISCOVER cards. Prices effective U.S.A. only. appy New Year! I hope you all to cross a pixe-' had a super Sega® Holiday! Are lated screen, H your fingers a little tired just like the from playing your new games? If so, movie. give 'em a stretch and get ready REGGIE JACI? because it's 1989; time for a whole new SON™ BASEBALL-The hot- season of Sega fun and games. Just test video baseball game I've ever take a look at what's coming down the played. Reggie is a modern legend (and video highway for you this year. a real decent dude). This game does R-TYPE™ -This game is so close to him justice. You'll love it! the hit arcade version that you'll be That's just in this issue. There's scanning the night skies, looking for even more on the way like the adven- attack ships from the Bydo Empire ture role-play game Y's (say "ies ") and (anybody know where that is?) a hot new SegaScope ™ 3-D, riit: GOLVELLIUS™: VALLEY OF POSEIDON WARS™ 3-D. -

NARRATIVE ENVIRONMENTS from Disneyland to World of Warcraft

Essay Te x t Celia Pearce NARRATIVE ENVIRONMENTS From Disneyland to World of Warcraft In 1955, Walt Disney opened what many regard as the first-ever theme park in Anaheim, California, 28 miles southeast of Los Angeles. In the United States, vari- ous types of attractions had enjoyed varying degrees of success over the preceding 100 years. From the edgy and sometimes scary fun of the seedy seaside boardwalk to the exuberant industrial futurism of the World’s Fair to the “high” culture of the museum, middle class Americans had plenty of amusements. More than the mere celebrations of novelty, technology, entertainment and culture that preceded it, Disneyland was a synthesis of architecture and story (Marling 1997). It was a revival of narrative architecture, which had previously been reserved for secular functions, from the royal tombs of Mesopotamia and Egypt to the temples of the Aztecs to the great cathedrals of Europe. Over the centuries, the creation of narrative space has primarily been the pur- view of those in power; buildings whose purpose is to convey a story are expensive to build and require a high degree of skill and artistry. Ancient “imagineers” shared some of the same skills as Disney’s army of creative technologists: they understood light, space flow, materials and the techniques of illusion; they could make two dimensions appear as three and three dimensions appear as two; they understood the power of scale, and they developed a highly refined vocabulary of expressive techniques in the service of awe and illusion (Klein 2004). Like the creators of Disney- land, they built synthetic worlds, intricately planned citadels often set aside from the day-to-day bustle of emergent, chaotic cities or serving as a centerpiece of es- cape within them. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

Thf SO~Twarf Toolworks®Catalog SOFTWARE for FUN & INFORMATION

THf SO~TWARf TOOlWORKS®CATAlOG SOFTWARE FOR FUN & INFORMATION ORDER TOLL FREE 1•800•234•3088 moni tors each lesson and builds a seri es of personalized exercises just fo r yo u. And by THE MIRACLE PAGE 2 borrowi ng the fun of vid eo ga mes, it Expand yo ur repertoire ! IT'S AMIRAClf ! makes kids (even grown-up kids) want to The JI!/ irac/e So11g PAGE 4 NINT!NDO THE MIRACLE PIANO TEACHING SYSTEM learn . It doesn't matter whether you 're 6 Coflectioll: Vo/11111e I ~ or 96 - The Mirttcle brings th e joy of music adds 40 popular ENT!RTA INMENT PAGE/ to everyo ne. ,.-~.--. titles to your The Miracle PiC1110 PRODUCTI VITY PAGE 10 Tet1dti11gSyste111, in cluding: "La Bamba," by Ri chi e Valens; INFORMATION PAGElJ "Sara," by Stevie Nicks; and "Thi s Masquerade," by Leon Russell. Volume II VA LU EP ACKS PAGE 16 adds 40 MORE titles, including: "Eleanor Rigby," by John Lennon and Paul McCartney; "Faith," by George M ichael; Learn at your own pace, and at "The Girl Is M in e," by Michael Jackson; your own level. THESE SYMBOLS INDICATE and "People Get Ready," by C urtis FORMAT AVAILABILITY: As a stand-alone instrument, The M irt1de Mayfield. Each song includes two levels of play - and learn - at yo ur own rivals the music industry's most sophis playin g difficulty and is full y arra nged pace, at your own level, NIN TEN DO ti cated MIDI consoles, with over 128 with complete accompaniments for a truly ENTERTAINMENT SYST!M whenever yo u want. -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

BIONIC COMMANDO “CHAIN of COMMAND” by Andy Diggle

BIONIC COMMANDO “CHAIN OF COMMAND” by Andy Diggle www.andydiggle.com PAGE 1 Hey Colin, welcome to the party! These first few pages are fairly exposition-heavy, so please do let me know if I haven’t left you enough room for the dialogue. But don’t worry, the blab-level should drop once we start blowin’ shit up real good... It’s not a hard-and-fast rule, but where possible it would be cool if you could try to favor full-width panels; this’ll make it easier to slice it up into a web-friendly format. As always, if you have any questions or concerns, don’t hesitate to drop me a line and I can re-work the script where necessary. Have fun! 1) A twin-rotor MILITARY TRANSPORT VTOL thunders dramatically towards us through gunmetal skies. Circa 2035 A.D. tech level. CAPTION I don’t look out the window any more. It hurts too much. CAPTION All that sky. All that freedom. 2) BIG! Reverse angle; the VTOL descends towards the TASC BIONICS DIVISION HQ - a heavily-fortified bunker-like complex with the TASC logo (the tesselated hexagons on the BC game logo) emblazoned on the side. Heavy blast doors yawn open to reveal a deep, cylindrical landing shaft atop the structure, like the mouth of a squat concrete volcano. Most of the complex lies deep underground, and all we’re seeing here is the tip of the iceberg. CAPTION This metal box is my whole world now. CAPTION But since I lost everything.. -

Game Wizard Game List

Game Wizard Game List 88 Games Blue's Journey 1942 Bomb Jack 1943 Bottom of the Ninth 1943 Kai Boulder Dash 1944: The Loop Master Breakers 2020 Super Baseball Breakers Revenge 3 Count Bout Bubble Bobble 4-D Warriors Burger Time Act-Fancer Hyper Weapon Burglar X Aero Fighters 2 Burning Fight Aero Fighters 3 Cabal Aggressors of Dark Kombat Cadillacs and Dinosaurs Airwolf Cadillacs and Dinosaurs Plus Alien vs. Predator Capcom Sports Club Aliens Captain Commando Alpha Mission II Captain Tomaday Amidar Carrier Air Wing Andro Dunos Caveman Ninja Area 88 Centipede Arkanoid Champion Wrestler Armored Warriors Chiki Chiki Boys Art of Fighting Chimera Beast Art of Fighting 2 Choky! Choky! Art of Fighting 3 Chuka Taisen Aurail Cobra-Command B.C. Story Combat School Bad Dudes vs. Dragon Ninja Congo Bongo Bad Lands Cookie & Bibi 2 Bang Bead Cookie & Bibi 3 Bank Panic Crime City Baseball Stars 2 Crime Fighters Baseball Stars Professional Crime Fighters 2 Batman (1P) Crossed Swords Battle Circuit Crude Buster Battle Flip Shot Crush Roller Battle Rangers Cyber-Lip Big Striker Cyberbots: Fullmetal Madness Biomechanical Toy (1P) D-Con Bionic Commando Dark Seal Blade Master Darkstalkers: The Night Warriors Blazing Star Demon's World Block Hole Diamond Run Blocken Dig Dug Blood Bros. Dig Dug II www.arcadespareparts.com 1 Game Wizard Game List Dino Rex Giga Wing Diver Boy Goal! Goal! Goal! Don Doko Don Golden Axe Donkey Kong Gondomania Donkey Kong 3 Gradius Donkey Kong Junior Gradius II - GOFER no Yabou Double Dragon Gradius III Double Dragon Great 1000 Miles Rally Dragon Breed Growl Dragon Unit Gun.Smoke Dragon World II (ver 100C)(1P) Gururin Dungeons & Dragons: Shadow over Gyruss Mystara Hachoo! Dungeons & Dragons: Tower of Doom Hard Head Dynamite Dux Hatch Catch E-Swat Hatris Head Panic E.D.F. -

Vgarchive : My Video Game Collection 2021

VGArchive : My Video Game Collection 2021 Nintendo Entertainment System 8 Eyes USA | L Thinking Rabbit 1988 Adventures in the Magic Kingdom SCN | L Capcom 1990 Astérix FRA | L New Frontier / Bit Managers 1993 Astyanax USA | L Jaleco 1989 Batman – The Video Game EEC | L Sunsoft 1989 The Battle of Olympus NOE | CiB Infinity 1988 Bionic Commando EEC | L Capcom 1988 Blades of Steel SCN | L Konami 1988 Blue Shadow UKV | L Natsume 1990 Bubble Bobble UKV | CiB Taito 1987 Castlevania USA | L Konami 1986 Castlevania II: Simon's Quest EEC | L Konami 1987 Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse FRA | L Konami 1989 Chip 'n Dale – Rescue Rangers NOE | L Capcom 1990 Darkwing Duck NOE | L Capcom 1992 Donkey Kong Classics FRA | L Nintendo 1988 • Donkey Kong (1981) • Donkey Kong Jr. (1982) Double Dragon USA | L Technōs Japan 1988 Double Dragon II: The Revenge USA | L Technōs Japan 1989 Double Dribble EEC | L Konami 1987 Dragon Warrior USA | L Chunsoft 1986 Faxanadu FRA | L Nihon Falcom / Hudson Soft 1987 Final Fantasy III (UNLICENSED REPRODUCTION) USA | CiB Square 1990 The Flintstones: The Rescue of Dino & Hoppy SCN | B Taito 1991 Ghost'n Goblins EEC | L Capcom / Micronics 1986 The Goonies II NOE | L Konami 1987 Gremlins 2: The New Batch – The Video Game ITA | L Sunsoft 1990 High Speed ESP | L Rare 1991 IronSword – Wizards & Warriors II USA | L Zippo Games 1989 Ivan ”Ironman” Stewart's Super Off Road EEC | L Leland / Rare 1990 Journey to Silius EEC | L Sunsoft / Tokai Engineering 1990 Kings of the Beach USA | L EA / Konami 1990 Kirby's Adventure USA | L HAL Laboratory 1993 The Legend of Zelda FRA | L Nintendo 1986 Little Nemo – The Dream Master SCN | L Capcom 1990 Mike Tyson's Punch-Out!! EEC | L Nintendo 1987 Mission: Impossible USA | L Konami 1990 Monster in My Pocket NOE | L Team Murata Keikaku 1992 Ninja Gaiden II: The Dark Sword of Chaos USA | L Tecmo 1990 Rescue: The Embassy Mission EEC | L Infogrames Europe / Kemco 1989 Rygar EEC | L Tecmo 1987 Shadow Warriors FRA | L Tecmo 1988 The Simpsons: Bart vs. -

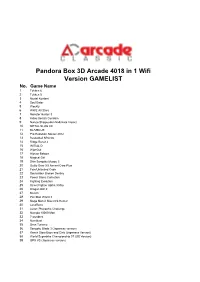

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech