Cavalry Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection Focuses on Important Pieces of 19Th-Century Texas Silver

YA L E UNIVERSITY A R T PRESS For Immediate Release GALLERY RELEASE August 15, 2017 SELECTIONS FROM THE WILLIAM J. HILL COLLECTION ON VIEW AT THE YALE UNIVERSITY ART GALLERY Collection focuses on important pieces of 19th-century Texas silver August 15, 2017, New Haven, Conn.—The Yale University Art Gallery is pleased to present an installation of twenty-seven pieces of Texas silver lent by Houston businessman and philanthropist William J. Hill. The silver will be on view through December 10, 2017, in the museum’s gallery devoted to the arts of New France, New Spain, and Texas, on the first floor of Street Hall. Hill has been an enthusiastic collector of Texas-made objects and a gener- ous donor of Texas-made furniture, ceramics, and other works of art to the Gallery, some of View of the installation of Texas silver lent by William J. Hill, which are shown alongside the silver. American decorative arts galleries, Yale University Art Gallery The history of the territory that became the state of Texas is complex. Spanish conquista- dors arrived in Texas in the 16th century, and by the late 17th century the Spanish had established an outpost at El Paso. At the same time, France was vying with Spain over control of the land in the Mississippi Valley, including the area called Texas. When Mexico won its independence from Spain in 1821, Texas became part of Mexico. Following a revolt against the Mexican government in 1835 to 1836, Texas became a republic, although Mexico did not recognize it. The United States annexed Texas as a state in 1845, and at the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848, Mexico acknowledged its independence. -

Finding Aid (704.4 Kb )

Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library Finding Aid for Series III: Unpublished Materials The Papers of Ulysses S. Grant Collection January 4, 1868 – March 9, 1869 Finding Aid Created: October 8, 2020 Searching Instructions for Series III: Unpublished Materials, of the Papers of Ulysses S. Grant Collection When searching for names in Series III: Unpublished Materials of the Papers of Ulysses S. Grant Collection, the researcher must take note of the manner in which the Papers of Ulysses Grant editorial project maintained its files. Names of individuals who often corresponded with, for, or about General Grant were shortened to their initials for the sake of brevity. In most instances, these individuals will be found by searching for their initials (however, this may not always be the case; searching the individual’s last name may yield additional results). The following is a list of individuals who appear often in the files, and, as such, will be found by searching their initials: Arthur, Chester Alan CAA Jones, Joseph Russell JRJ Babcock, Orville Elias (Aide) OEB Lagow, Clark B. CBL Badeau, Adam AB Lee, Robert Edward REL Banks, Nathaniel Prentiss NPB Lincoln, Abraham AL Bowers, Theodore S. (Aide) TSB McClernand, John Alexander JAM Buell, Don Carlos DCB McPherson, James Birdseye JBM Burnside, Ambrose Everett AEB Meade, George Gordon GGM Butler, Benjamin Franklin BFB Meigs, Montgomery Cunningham MCM Childs, George W. GWC Ord, Edward Ortho Cresap ORD Colfax, Schuyler SC Parke, John Grubb JGP Comstock, Cyrus B. CBC Parker, Ely Samuel ESP Conkling, Roscoe RC Porter, David Dixon DDP Corbin, Abel Rathbone ARC Porter, Horace (Aide) HP Corbin, Virginia Grant VGC Rawlins, John Aaron JAR Cramer, Mary Grant MGC Rosecrans, William Starke WSR Cramer, Michael J. -

Fort Fillmore

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 6 Number 4 Article 2 10-1-1931 Fort Fillmore M. L. Crimmins Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Crimmins, M. L.. "Fort Fillmore." New Mexico Historical Review 6, 4 (1931). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol6/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW -'.~'-""----""'-'-'.'~ ... --- _.--'- . .--.~_._ ..._.._----., ...._---_._-_._--- --~----_.__ ..- ... _._._... Vol. VI. OCTOBER, 1931 No.4. --_. -'- ."- ---_._---_._- _._---_._---..--. .. .-, ..- .__.. __ .. _---------- - ------_.__._-_.-_... --- - - .._.....- .. - FORT FILLMORE By COLONEL M. L. CRIMMINS ABOUT thirty-eight miles from El Paso, on the road to Las I"l.. Cruces on Highway No. 80, we pass a sign on the rail road marked "Fort Fillmore." About a mile east of this point are the ruins of old Fort Fillmore, which at one time was an important strategical point on the Mexican border. In 1851, the troops were moved from Camp Concordia, now I El Paso, and established at this point, and the fort was named after President Millard Fillmore. Fdrt Fillmore was about three miles southeast of Mesilla, which at that time was the largest town in the neighborhood, El Paso hav~ng only about thirty Americans and some two hundred Mexicans. -

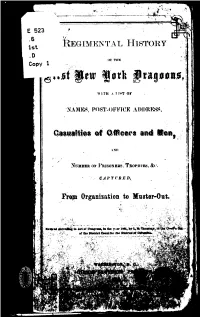

Regimental History of the First New York Dragoons, with a List of Names, Post-Office Address, Casualties of Officers and Men, An

G!ass E~SFS-- ,C- Book sr -- I * ; rid? - TJ-IT11 -4 LIST OX Sa_su;a!tieoaP QRclera and Nee, A T [I X'SLI;I'ROF ~'I:IBC~SERS,TROPIIIEB, kc. CAPTCRED, From Organization to Musk-Out, JYhS1IISGIOS. D. C. GIGSC1S RIZOTHERS, PRISTERS, 1835. Tl~cbra\-c Dragoons ! the 'orare Dragoons! God bless the home that gave them birth ! That land has gained a fairer fame Than any other land on earth. Hail ! hail, ye heroes ! Fill the 11ow.l ! And lxoudly greet these sons of Mars! Fill high the bowl! Gire thrice three cheer? For every valiant hero's scars! They come from Dixie's boasted land : Bring laurels for each hero's brow, And let them feel: (though ever loved:) We fly to greet and bless them now. We know how boldly they hare fought. And Ivan full many a bloody field ; Ho! cheer we then the brave Dragoons. Wl~oforced the traitor foe to yield! Come maid and matron, sire and son, From mansion. hall, and cottage, come- .Ind come with song axid joy and wine To ~velcomeerery hero home. Bling floacis to wreathe each battle blade- Bring garlands For tlieir scars and wounds : And let the rerl- hills unite In cheers to greet the brare Dragoons ! Roc~:es~ea,June 20.1'4:. KEGINEXTBL HISTORY. Tl!c i~lontliof July, 13.2. will ever l!c rciiie~nberedfur the cu1uiin:ltion at IIarrison's Landing of JlcClellan's dis- astrolls ~i~nipaig~ion t!ie Peninsnl:~. ,I gigantic e%rt had been put fort!^, and !lad resulted in a sign:~lfirilurc. -

Swamp Angel Ii

NEWSNEWS SWAMP ANGEL II VOL 28, NO. 2 BUCKS COUNTY CIVIL WAR MUSEUM AND ROUND TABLE APR/JUN2019 NEWS AND NOTES Message from the President CALENDER Apr, 2019 - Michael Kalichak, “The Fourth Texas Volun- Spring is just around the corner and the museum has had a busy teer Infantry in the War of the Rebellion” few months. I wanted to point out just a few highlights thus far. First of all, I wanted to thanks those involved who made the first May, 2019 - Kevin Knapp, "Military Ballooning during quarter a great success. Gerry Mayers and Jim Rosebrock gave the Civil War" wonderful presentations at our monthly meetings on both Civil Jun, 2019 - Katie Thompson, "To the Breaking Point: The War Music as well as Artillery at Antietam, and both were very Toll of War on the Civil War Soldier” well received. In addition, George Hoffman led a thoughtful and Meetings are held the first Tuesday of each month at 7 pm at Doylestown Borough Hall, always intriguing book review, this time of “Lee's Real Plan at 57 W. Court Street unless otherwise noted. For more information on specific dates, visit Gettysburg.” The Fund Raising Committee met again to discuss our site at www.civilwarmuseumdoylestown.org ways to increase funding and Dick Neddenriep offered his exper- ♦ Congratulations to last quarter’s raffle winners: tise and knowledge to train some new museum tour docents. A Marilyn Becker, Ron DeWitt, Walter Fellman, Sue hearty thanks to all for your time and effort in making our mission Damon, and Judith Folan. superb! ♦ Work has begun on the new Bucks County Parking Now for some things coming up...Look forward to Michael Ka- Garage. -

The Story of Comanche: Horsepower, Heroism and the Conquest of the American West

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Jones, Karen R. (2017) The Story of Comanche: Horsepower, Heroism and the Conquest of the American West. War and Society, 36 (3). pp. 156-181. ISSN 0729-2473. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/07292473.2017.1356588 Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/56325/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html War & Society ISSN: 0729-2473 (Print) 2042-4345 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ywar20 The story of Comanche: horsepower, heroism and the conquest of the American West Karen Jones To cite this article: Karen Jones (2017) The story of Comanche: horsepower, heroism and the conquest of the American West, War & Society, 36:3, 156-181, DOI: 10.1080/07292473.2017.1356588 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07292473.2017.1356588 © 2017 The Author(s). -

VOL. 1873 Fourth Annual Reunion of the Association of the Graduates of the United States Military Academy, at West Point, New Yo

FOURTH ANNUAL REUNION OF THE OF THE UNITED STATES MILITARY ACADEMY, AT WEST SOIVT, JNEW YO(K, JUNE 1, 1873. NEW YORK: D. VAN NOSTRAND, PUBLISHER, 23 MURRAY AND 27 WARREN STREET. 1873. ANNUAL REUNION JUNE 12, 1873. MINUTES OF THE BUSINESS MEETING. WEST POINT, N. Y., June 12th, 1873. The Association met in the Chapel of the United States Military Academy, and was called to order by Judge R. P. Parrott, Class of 1824, Chairman of the Executive Committee. Prayer was offered by the Rev. C. C. Parsons, Class of 1861 (June). The roll of the Members of the Association was then called by the Secretary. ROLL OF MEMBERS. Those present are indicated by a *, and those deceased in italics. Class. Class. 1808 Sylvanus Thayer. (Dennis H. Mahan. 1824 \ *ROBERT P. PARROTT. *SIMON WILLARD. (JOHN M. FESSENDEN. James Munroe. 1815 THOMAS J. LESLIE. 1825 N. SAYRE HARRIS. CHARLES DAVIES. *WILLIAM H. C. BARTLETT. Horace Webster. *SAMUEL P. HEINTZELMAN. 1818 HARVEY BROWN. 1826 AUGUSTUS J. PLEASONTON. Hacrtman Bache. *NATHANIELX C. MACRAE. EDWIN B. BABBIT. EDWARD D. MANSFIELD. l *SILAS CASEY. HENRY BREWERTON. 1819 HENRY A. THOMPSON. ALEXANDER J. CENTER. *DANIEL TYLER. 1827 NATHANIEL J. EATON. WILLIAM H. SWIFT. Abraham Van Buren. 1820 RAWLINS LOWNDES. *ALBERT E. CHURCH. 1828 GUSTAVE S. ROUSSEAU. 1821 *SETH M. CAPRON. CRAFTS J. WRIGHT. *WILLIAM C. YOUNG. f CATH. P. BUCKINGHAM. David H. Vinton. SIDNEY BURBANK. 18 *BENJAMIN H. WRIGHT. WILLIAM HOFFMAN. DAVID HUNTER. THOMAS SWORDS. 1829 ALBEMARLE CADY. GEORGE S. GREENE. *THOMAS A. DAVIES. *HANNIBAL DAY. *CALEB C. SIBLEY. 8 GEORGE H. CROSMAN. JAMES CLARK. -

Fort Fillmore, Nm, 1861

FORT FILLMORE, N.M., 1861: PUBLIC DISGRACE AND PRIVATE DISASTER Author(s): A. Blake Brophy Source: The Journal of Arizona History , Winter 1968, Vol. 9, No. 4 (Winter 1968), pp. 195-218 Published by: Arizona Historical Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41695494 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Arizona Historical Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Arizona History This content downloaded from 81.245.179.18 on Sat, 27 Mar 2021 15:32:59 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms FORT FILLMORE, N.M., 1861: PUBLIC DISGRACE AND PRIVATE DISASTER by A. Blake Brophy The author, a native Arizonan and a former journalist, became inter- ested in the story of the surrender of Fort Fillmore while doing graduate work at Arizona State University. He received his master's degree this past autumn. LYDIA J 1856,J 1856, although SPENCER she had although been married she LANE only hadtwo beenyears wasto her married a seasoned only two "trooper" years to her in lieutenant of U.S. Mounted Rifles.* The daughter of an army officer, she had grown up in army posts of all sorts, but when she got her first look at Fort Fillmore, N.M., she remembered that it was "such a dreary-looking place [as] I have seldom seen."1 Located about forty miles north of El Paso on the east side of the Rio Grande,2 the sand-hill fort, established in 1851 against Indian depredations, appears to have been as Mrs. -

8Th New York Cavalry Also Known As: the Rochester Regiment, the Crooks Cavalry Regiment Colonels: Samuel J

Regimental Histories 8th New York Cavalry Also known as: The Rochester Regiment, The Crooks Cavalry Regiment Colonels: Samuel J. Crooks, Alfred Gibbs, Benjamin F. "Grimes" Davis, William L. Markell, William H. Benjamin, Edmund M. Pope Recruitments: from the counties of Monroe, Ontario, Seneca, Wayne, Orleans, Niagara, Chenango, and Oneida Dates of Service: Organized at the Rochester Fairgrounds, Rochester NY Mustered in November 23 and 28, 1861, to October 4, 1862 to serve for three years Mustered out of service on June 27, 1865 Major Engagements: Winchester, Antietam, Upperville, Barbee's Cross Roads, Beverly Ford, Gettysburg, Locust Grove, Hawe's Shop, Wilson's Raid, White Oak Swamp, Opequan, Cedar Creek, Appomattox Campaign Upon muster, the regiment's officers were: Colonel Samuel J. Crooks Lt. Colonel Charles R. Babbitt Major William L. Markell Major William H. Benjamin Adjutant Albert L. Ford Surgeon James Chapman Asst. Surgeon Winfield S. Fuller Chaplain John H. Van Ingen Co. A - Captain Edward M. Pope, 1st Lt. Alfred Leggett, 2nd Lt. Alfred E. Miller Co. B - Captain Caleb Moore, 1st Lt. Henry Cutler, 2nd Lt. John A. Broadhead Co. C - Captain John W. Dickinson, 1st Lt. John W. Brown, 2nd Lt. Frederick W. Clemons Co. D - Captain William Frisbie, 1st Lt. Ezra J. Peck, 2nd Lt. Albert L. Ford Co. E - Captain Benjamin F. Sisson, 1st Lt. Frank O. Chamberlain, 2nd Lt. Samuel E. Sturdevant Co. F - Captain Fenimore T. Gallett, 1st Lt. Thomas Bell, 2nd Lt. William D. Bristol Co. G - Captain William H. Healy, 1st Lt. William H. Webster, 2nd Lt. Frederick Scoville Co. H - Captain John Weiland, 1st Lt. -

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A

Collection 1805.060.021: Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers in the Civil War in America – Collection of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index The Heritage Center of The Union League of Philadelphia 140 South Broad Street Philadelphia, PA 19102 www.ulheritagecenter.org [email protected] (215) 587-6455 Collection 1805.060.021 Photographs of Union and Confederate Officers - Collection of Bvt. Lt. Col. George Meade U.S.A. Alphabetical Index Middle Last Name First Name Name Object ID Description Notes Portrait of Major Henry L. Abbott of the 20th Abbott was killed on May 6, 1864, at the Battle Abbott Henry L. 1805.060.021.22AP Massachusetts Infantry. of the Wilderness in Virginia. Portrait of Colonel Ira C. Abbott of the 1st Abbott Ira C. 1805.060.021.24AD Michigan Volunteers. Portrait of Colonel of the 7th United States Infantry and Brigadier General of Volunteers, Abercrombie John J. 1805.060.021.16BN John J. Abercrombie. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Brigadier General Geo. (George) Stoneman Chief of Cavalry, Army of the Potomac, and staff, including Assistant Surgeon J. Sol. Smith and Lieutenant and Assistant J. Adjutant General A.J. (Andrew Jonathan) Alexander A. (Andrew) (Jonathan) 1805.060.021.11AG Alexander. Portrait of Captain of the 3rd United States Cavalry, Lieutenant Colonel, Assistant Adjutant General of the Volunteers, and Brevet Brigadier Alexander Andrew J. -

The Case of Major Isaac Lynde

New Mexico Historical Review Volume 36 Number 1 Article 2 1-1-1961 The Case of Major Isaac Lynde A. F.H. Armstrong Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr Recommended Citation Armstrong, A. F.H.. "The Case of Major Isaac Lynde." New Mexico Historical Review 36, 1 (1961). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmhr/vol36/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Historical Review by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. NEW MEXICO HISTORICAL REVIEW VOL. XXXVI JANUARY, 1961 NO.1 THE CASE ·OF MAJOR ISAAC LYNDE By A. F. H. ARMSTRONG N January 27, 1861, at San Augustine Springs, New O Mexico Territory, Major Isaac Lynde, 7th U.S. Infan try, surrendered his entire command to an inferior force of Confederate troops led by Lieutenant-Colonel John R. Baylor, Mounted Rifles, C.S.A.. Reports filed by both sides at the time agree that Lynde surrendered to an inferior force. They agree on the date and place. They disagree somewhat on the size and composition of Lynde's command and the Confederate command. They disagree widely on the causes for Lynde's surrender. I propose to draw on all the material that contributes to a picture of Major Lynde, his action and its causes, and to arrange this into a cohesive whole, hoping the truth may emerge more clearly than it has heretofore without such correlation. -

Regimental History of the First New York Dragoons

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com WIDENER LIBRARY HX 2P7E C History First New York & Dragoons & ils 5968.5.130 THE COLLEGE LIBRARY Purchased from the income of a fund for American History bequeathed by Annielouise Bliss Warren in memory of her husband CHARLES WARREN '89 VERI TAS HARVARD UNIVERSITY 1 { 1 1 REV . JAMES R. BOWEN From a late photograph REGIMENTAL HISTORY OF THE First New York Dragoons ( Originally the 130th N. Y. Vol . Infantry ) DURING THREE YEARS OF ACTIVE SERVICE IN THE GREAT CIVIL WAR BY REV . J. R. BOWEN ALFRED GIBBS 130 30 YORK N.Y.VO , . 1865 CAV . NY Our Motto : “ SEMPER PARATUS " ( Always ready ) PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR 1900 1 : 5.178.5.10 HARVARD UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SEP 24 1965 PREFACE The preparation of this history has been carried forward with mingled feelings of pleasure and pain . In my really laborious search after historic material I have been singularly carried back , and have lived over those three eventful years of our regimental service . Like the successive presentations of a moving panorama , their scenes have vividly seemed to pass in review . · Names of comrades , with their forms and faces , are recalled after the lapse of more than a third of a century , as if but yesterday . The battlefield with its movements of troops , the roar of cannon and rattle of small arms , the ringing commands of officers , the groans of the wounded and dying soldiers , are again living realities .