Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Literature Knows: Forays Into Literary Knowledge Production

Contributions to English 2 Contributions to English and American Literary Studies 2 and American Literary Studies 2 Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Antje Kley / Kai Merten (eds.) Kai Merten (eds.) Merten Kai / What Literature Knows This volume sheds light on the nexus between knowledge and literature. Arranged What Literature Knows historically, contributions address both popular and canonical English and Antje Kley US-American writing from the early modern period to the present. They focus on how historically specific texts engage with epistemological questions in relation to Forays into Literary Knowledge Production material and social forms as well as representation. The authors discuss literature as a culturally embedded form of knowledge production in its own right, which deploys narrative and poetic means of exploration to establish an independent and sometimes dissident archive. The worlds that imaginary texts project are shown to open up alternative perspectives to be reckoned with in the academic articulation and public discussion of issues in economics and the sciences, identity formation and wellbeing, legal rationale and political decision-making. What Literature Knows The Editors Antje Kley is professor of American Literary Studies at FAU Erlangen-Nürnberg, Germany. Her research interests focus on aesthetic forms and cultural functions of narrative, both autobiographical and fictional, in changing media environments between the eighteenth century and the present. Kai Merten is professor of British Literature at the University of Erfurt, Germany. His research focuses on contemporary poetry in English, Romantic culture in Britain as well as on questions of mediality in British literature and Postcolonial Studies. He is also the founder of the Erfurt Network on New Materialism. -

It's a Mystery Knowledge Organiser

Christ’s College English Department Ignite 2 Unit 1: It’s A Mystery Knowledge Organiser – Year 8 Key Learning – Exploring the Mystery Genre What is a mystery story? Key features of a mystery: A mystery needs to keep The word ‘mystery’ is derived from the Anglo-French misterie, or the old French mistere, ▪ A puzzling problem or crime the reader turning the meaning secret, mystery, hidden meaning. Additionally the modern French mystère and ▪ A detective or investigator pages by building up Latin mysterium had meanings of a secret rite, secret worship, a sacrament, a secret ▪ Suspects and a villain tension and suspense. thing. ▪ A trail of clues There needs to be ▪ A final plot twist jeopardy, memorable The History of the Mystery characters and a plot twist. The roots of the mystery genre can be traced back to the 18th century, when stories of real-life crime, and the biographies of notorious criminals, were published in The Characters Newgate Calendar. (Newgate was a famous prison in London, where condemned You will find many different characters in a mystery story: victims, prisoners were held before being executed at Tyburn gallows.) In the first half of the 19th suspects and villains, but the most important character is often the century, readers could find sensationalist stories of crime and mystery in ‘penny detective – the person investigating the mystery itself. This could dreadfuls’ – inexpensive novels printed on cheap paper and published in instalments. be: an amateur sleuth, a private investigator or a police detective. ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ (a short story written in 1841 by Edgar Allan Poe) is viewed by many people as the first classic mystery story. -

Tragedy After Darwin by Manya Lempert a Dissertation Submitted In

Tragedy after Darwin by Manya Lempert A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Dorothy Hale, Chair Professor Ann Banfield Professor Catherine Gallagher Professor Barry Stroud Summer 2015 Abstract Tragedy after Darwin by Manya Lempert Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Dorothy Hale, Chair Tragedy after Darwin is the first study to recognize novelistic tragedy as a sub-genre of British and European modernism. I argue that in response to secularizing science, authors across Europe revive the worldview of the ancient tragedians. Hardy, Woolf, Pessoa, Camus, and Beckett picture a Darwinian natural world that has taken the gods’ place as tragic antagonist. If Greek tragic drama communicated the amorality of the cosmos via its divinities and its plots, the novel does so via its characters’ confrontations with an atheistic nature alien to redemptive narrative. While the critical consensus is that Darwinism, secularization, and modernist fiction itself spell the “death of tragedy,” I understand these writers’ oft-cited rejection of teleological form and their aesthetics of the momentary to be responses to Darwinism and expressions of their tragic philosophy: characters’ short-lived moments of being stand in insoluble conflict with the expansive time of natural and cosmological history. The fiction in this study adopts an anti-Aristotelian view of tragedy, in which character is not fate; character is instead the victim, the casualty, of fate. And just as the Greek tragedians depict externally wrought necessity that is also divorced from mercy, from justice, from theodicy, Darwin’s natural selection adapts species to their environments, preserving and destroying organisms, with no conscious volition and no further end in mind – only because of chance differences among them. -

Tragic Mercies and Other Journeys to Redemption

TRAGIC MERCIES AND OTHER JOURNEYS TO REDEMPTION: DEFINING THE MORRISONIAN TRAGEDY by ASHLEY NICOLE BURGE TRUDIER HARRIS, COMMITTEE CHAIR CASSANDER SMITH CAJETAN IHEKA YOLANDA MANORA PEARL MCHANEY A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2019 Copyright Ashley Nicole Burge 2019 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Tragic Mercies and Other Journeys to Redemption: Defining the Morrisonian Tragedy problematizes current portrayals of tragedy and tragic acts in African American literature. Using Toni Morrison’s Beloved as a foundational text, I argue that Morrison executes a literary aesthetic that disrupts traditional constructs of the tragedy that elevate Eurocentric ideologies at the expense of Black identity and subjectivity. This aesthetic challenges the portrayal of the “tragic figure,” positioning it as an inadequate trope that nullifies the complexities associated with the lived reality of Africans/African Americans under repressive systems such as American slavery. Morrison reconfigures tragedy to illuminate a space that she calls the “tragic mode” in which her characters achieve a form of catharsis and revelation. I use Morrison’s signification of tragedy to build a theoretical paradigm that I call the Tragic Mercy which interprets tragedy and tragic acts, such as infanticide in her neo-slave narrative Beloved (1987), as events that symbolize activism against oppressive systems connected to racist capitalist patriarchal ideologies. The Tragic Mercy is the lens through which I define the Morrisonian tragedy, and I articulate it as an act that generates a physical and psychological journey that leads to redemption, catharsis, and reclamation. -

Book Review of Fight Club Written by Chuck Palahniuk

Book Review of Fight Club Written By Chuck Palahniuk Adityo Widhi Nugroho – 13020112130050 Fakultas Ilmu Budaya Diponegoro University 1. INTRODUCTION The writer intends to review Fight Club written by Chuck Palahniuk. The novel is one of the examples of literary nonfiction. Published in 1996 by W.W Norton, this novel became top selling novel according to Baltimore Sun. Fight Club, written by Chuck Palahniuk has been adapted into a movie, a prequel novel and a comic book sequel. According to The Baltimore Sun this novel is very controversial because of the anarchism and anti-consumerism behaviour done by the characters of the novel. The Baltimore Sun also writes “bravo to Norton for having the courage to publish it” (Hoffert 4). Furthermore violence also appeared in this novel as there are a lot of fight and other form of physical violence. The main purpose of this writing is to review Fight Club by Chuck Palahniuk. The writer will discuss the strengths and weaknesses of this novel . The writer decided to choose Fight Club as final project because it is his favorite novel. Fight Club is a very interesting novel although it is hard to understand and disturbing because by showing the consumerism behaviour in this novel, Chuck Palahniuk tries to convey the message that the consumerism behaviour of society nowadays has become worse than ever. 2. SUMMARY OF FIGHT CLUB The center story of Fight Club revolves around the life of an anonymous narrator, a typical American hard working man. Because of the stress caused by his job and tiresome business trips, he suffers insomnia. -

Only the Officially-Sanctioned Genres Will Be Allowed in This Field. We Assume That This Will Be Accomplished Through the Database (By a Pulldown Menu, for Example)

Only the officially-sanctioned genres will be allowed in this field. We assume that this will be accomplished through the database (by a pulldown menu, for example). We assume that the keyword field will be used for more specific information than will be captured in the official genres and that some of the information currently in the genre field will be moved to the keyword field. We recommend that in the future genres may be added to the official list based on their number of uses as keyword and their qualification as a genre. The aspect of age-appropriateness, previously reflected in such genres as Adult, Children, Teen, and reflected in many terms listed in lists of manga genres, is not in fact an aspect of genre. We recommend the addition of a field for publisher-supplied target age designations. We defer any recommendation on whether some sequence types should not accept genre identifications. Though a majority of the members of the committee thought that all stories could be assigned at least one of the first four genres (adventure, drama, humor, non-fiction), the majority of the committee also thought that the user should not be required to first choose one of the first four genres. While it is the intention that stories associated with a particular feature be assigned a genre consistent with the other stories of the feature, genre can also be assigned to stories that are not a part of a feature at all, as with the majority of the stories in the anthologies listed below as examples (Tales from the Crypt, Metal Hurlant, G.I. -

Pratap-Kumar-D

ISSN 2320 – 6101 Research Scholar www.researchscholar.co.in An International Refereed e-Journal of Literary Explorations INTERPRETATION OF TEXT, CONTEXT AND INTERTEXTUALITY IN GYNOTEXT: A STUDY OF TONI MORRISON’S A MERCY Dr. Pratap Kumar Dash Asstt.Prof. in English, Faculty of Education Brack Sebha University, Libya ABSTRACT A close reading of Toni Morrison’s A Mercy in this paper focuses on both the stylistic and thematic features through the interpretation of the distinct textual, contextual and intertextual elements. Firstly, as opposed to other researches done so far, it establishes the fact that the text drags readerly attention for two reasons like it is in medias res and the speech acts with heteroglossia ranging from daily life conversations to rhetorical expressions bear more importance than the prose narratives in shaping the configuration of it impressively. Secondly, with the traditional form of analysis, it attempts at focusing on the major contexts in it like traumatic memory; female subjugation; Afrocentric values; eco-feminism, Diaspora, marginality, literary historiography and canonization and discusses the novel as a demonic parody too. Thirdly, in the intertextual analysis, however, it deviates by arguing that although the novel is well-wrought with different themes as discussed earlier, it loses the gravity of gynotext with feminist force in comparison to the other contemporary feminist narratives ranging from African-American writings to Indian writings and Dalit writings and therefore hardly bears current social relevance except it is proved to be an autoethnographic narrative of ‘repetition with difference’. Keywords: in medias res, speech acts, heteroglossia, Afrocentric, subjugation, eco-feminism, gynotext, autoethnographic Vol. -

A Variety of Thrills

A Variety of Thrills Thrillers and different ways of approaching them K.A. Kamphuis, 3654621 Semester 2, 2012-2013 January 25 2013 J.S. Hurley Film Genres, Thrillers Abstract Thriller is a broad genre. This genre is constructed by the use of different people involved in the movie process; the producers and advertisers, critics and consumers. They all have different reasons to call a thriller a thriller. I did a discourse analysis on three movies to see whether the use of the term “thriller” is used by all this parties in the same way and how this will construct the genre. The three movies in that are analysed are The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011), Black Swan (2010) and Hide and Seek (2005). Index Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 Discursive Approaches ....................................................................................................... 5 Producers ....................................................................................................................... 5 Advertisers ..................................................................................................................... 7 Critics ............................................................................................................................. 8 Consumers ................................................................................................................... 10 Conclusion ....................................................................................................................... -

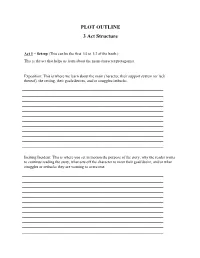

YES Plot Outline (Pdf)

PLOT OUTLINE 3 Act Structure Act 1 – Set-up (This can be the first 1/4 to 1/3 of the book.) This is the act that helps us learn about the main character/protagonist. Exposition: This is where we learn about the main character, their support system (or lack thereof), the setting, their goals/desires, and/or struggles/setbacks. Inciting Incident: This is where you set in motion the purpose of the story, why the reader wants to continue reading the story, what sets off the character to meet their goal/desire, and/or what struggles or setbacks they are wanting to overcome. Plot Point One: Setting the plot in a new direction. Meeting a bump in the road. FIRST PLOT TWIST! Act 2 – Confrontation (This can be the middle 1/3 to 1/2 of the book.) This act is meant to show us how the protagonist is able/unable to deal with the setbacks and complications that surface. This is an emotional journey for the protagonist. Rising Action(s): The small obstacles (and hopefully their resolutions) and a complication (or two) that could be serious/dangerous is introduced. Midpoint: This is where the protagonist’s world crashes down and makes them feel as if they have hit rock bottom (emotionally, physically, financially, morally, etc.). The DARK MOMENT! Plot Point Two: Another new direction. Another bump in the road. SECOND PLOT TWIST! Act 3 – Resolution (This can be the last 1/4 to 1/3 of the book.) This act is meant to show the resolution between the protagonist and the antagonist. -

Elements of Film

Elements of Film: "Storyline" versus “plot” or (events versus causation): The story is no more than the unfolding of events. A chronology (sometimes linear—sometimes non-linear) of occurrences—think “what” happens in the movie. In truth, there exists but a few storylines—think: “The rogue cop”, “the killer alien”, “the boy who looses the girl that he must get back”, -- each is a retelling of the same storyline--the modern Odyssey”…The concept of plot is much more complicated and necessitates much more thought. The plot usually necessitates some form of a pattern, unintended or intentional, that threads the story together. If the storyline equals “what” occurred, the plot is the “how”. The plot allows the conflict faced by the protagonist to end in some sort of resolution. It’s also the causation that allows the antagonist to fall. Well conceived plots usually consider: a) how characters come in conflict with one another b) how characters come in conflict with their surroundings and c) how characters come in conflict with themselves. W/o a realistic plot, your story will seem overly contrived and quite predictable. When I think of twisted plots, I always go back to “The Matrix”---( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8e-FF8MsqU) -- remember the first in the series—nothing was real—who saw that plot twist coming—not me…. Examples: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Rl1TJG17Wk – Project X Storyline: A group of high school outcasts throw a house party in attempt to become popular Plot: parents leave for the night, friend convinces protagonist to -

Episode 18: Consider It a Plot Twist

EPISODE 18: CONSIDER IT A PLOT TWIST Full Episode Transcript WITH YOUR HOST LAUREN CASH Episode 18: Consider It a Plot Twist 1 YOU ARE LISTENING TO THE EFFECTIVE ENTREPRENEUR PODCAST WITH LAUREN CASH, EPISODE 18: CONSIDER IT A PLOT TWIST. Hey, how’s it going? Are you having an amazing Monday? How’s your January going? Is it good? Are you hitting off 2021 with amazing speed and flying colors? I hope so. I have been loving starting off the new year in a new location. It’s nothing like the beginning of the year to start off the year in a brand new city. I’ve moved around so much the last three years, but I always love moving right at the end of a year and then being somewhere new in the beginning of the year because it just feels amazing to have a fresh start fully even in the location that you’re in at the beginning of the year. So stay tuned for me talking more about that. I’m sure I’ll have lots of behind the scenes on Instagram. If you don’t follow me there, let’s make sure to connect on Instagram @vivereco. So v-i-v-e-r-e-c-o. That’s always linked in the show notes too. I love connecting with you on Instagram. Shoot me a DM. Take a screenshot when you’re listening to your favorite episode of The Effective Entrepreneur Podcast, and share it with us so we can reshare and all connect together on that platform. -

Choose a Narrative Structure

Presentations need structure to hold a message and engage an audience Quinten Edward Williams Quinten Edward Williams [email protected] Narrative structure Linear and nonlinear narrative Aristotle’s Beginning, Middle, End Gustav Freytag’s Pyramid Freytag’s Pyramid and the Three Act Plot Christopher Brooker’s Meta Plot Visualizing narrative structure. (2018). Kensy Cooperrider. Retrieved 10 February 2019, from http://kensycooperrider.com/blog/visualizing-narrative-structure Narrative, Story, Plot, Narrative Structure Story = A series of events. The content. Conflicts. Characters. Settings. Plot = How the story is put together. It is a structure. How the series of events are set-up and resolved. Narrative = Story + Plot. It is a specific manifestation of a story. How audience receives the information. Narrative Structure = A structural framework that underlies the presentation of the narrative Poynzt, S. (2002). Visual storytelling and narrative structure. Vancouver, BC : Pacific Cinémathèque. Narrative Structure Categories Interactive Linear Nonlinear Narrative Plot follows Events are portrayed The user makes chronological order. are not in the original choices which affects Story is presented in chronological order. the plot direction. the order that events The plot does not Story elements are occurred. follow direct interactive. Immersed causality. in the story. https://www.interactivenarratives.org Mascolini, J. (2017) The Post Nonlinear Narrative Structure: Introduction. Medium. Retrieved 11 February 2019, from https://medium.com/@jacopomsn/the-post-nonlinear-narrative-structure-introduction-52f6dfe37377 Riedl, M., & Bulitko, V. (2012). Interactive Narrative: An Intelligent Systems Approach. AI Magazine, 34(1), 67. doi:10.1609/aimag.v34i1.2449 Aristotle: Beginning, Middle, End Plot with Unity of action “Tragedy is an imitation of an action that is complete, and whole, and of a certain magnitude.