CHAPTER V the Term Social Movement Generally Implies a Consistent Political Action by a Social Group to Achieve Certain Goals. A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

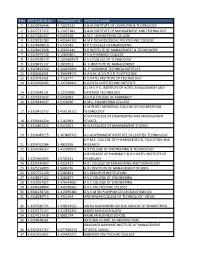

Sr. No. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region

Non-Aided College List Sr. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region Correspondence College No. Address Type 1 Shri. KGM Newaskar Sarvajanik Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Pandit neheru Hindi Non-Aided Trust's K.G. College of Arts & Pune University, ar ar vidalaya campus,Near Commerece, Ahmednagar Pune LIC office,Kings Road Ahmednagrcampus,Near LIC office,Kings 2 Masumiya College of Education Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune wable Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar colony,Mukundnagar,Ah Pune mednagar.414001 3 Janata Arts & Science Collge Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune A/P:- Ruichhattishi ,Tal:- Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar Nagar, Dist;- Pune Ahmednagarpin;-414002 4 Gramin Vikas Shikshan Sanstha,Sant Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune At Post Akolner Tal Non-Aided Dasganu Arts, Commerce and Science Pune University, ar ar Nagar Dist Ahmednagar College,Akolenagar, Ahmednagar Pune 414005 5 Dr.N.J.Paulbudhe Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune shaneshwar nagarvasant Non-Aided Science Women`s College, Pune University, ar ar tekadi savedi Ahmednagar Pune 6 Xavier Institute of Natural Resource Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Behind Market Yard, Non-Aided Management, Ahmednagar Pune University, ar ar Social Centre, Pune Ahmednagar. 7 Shivajirao Kardile Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Jambjamb Non-Aided Science College, Jamb Kaudagav, Pune University, ar ar Ahmednagar-414002 Pune 8 A.J.M.V.P.S., Institute Of Hotel Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag -

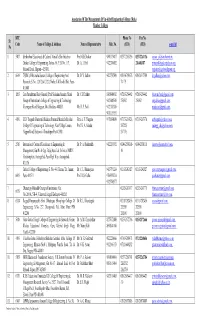

Closing Merit Sr

Closing Merit Sr. No. Institute Name Course Name Choice Code Closing Merit No Marks 1. Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute(VJTI), Matunga, Mumbai Computer Engineering 301224510 939 98.70066916 2. Institute of Chemical Technology, Matunga, Mumbai Chemical Engineering 303650710 961 98.67660212 3. College of Engineering, Pune Computer Engineering 600624510 1081 98.54044877 4. Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute(VJTI), Matunga, Mumbai Information Technology 301224610 1261 98.34833276 5. College of Engineering, Pune Information Technology 600624610 1287 98.31277480 6. Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute(VJTI), Matunga, Mumbai Mechanical Engineering 301261210 1540 98.04848945 7. College of Engineering, Pune Mechanical Engineering 600661210 1568 98.01562268 8. Institute of Chemical Technology, Matunga, Mumbai Polymer Engineering and Technology 303651910 1629 97.95162951 9. College of Engineering, Pune Electronics and Telecommunication Engg 600637210 1769 97.81820542 10. Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan's Sardar Patel Institute of Technology , Andheri, Mumbai Computer Engineering 321524510 1857 97.74260055 11. College of Engineering, Pune Electrical Engineering 600629310 1987 97.59642313 12. Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute(VJTI), Matunga, Mumbai Electronics and Telecommunication Engg 301237210 2000 97.57729023 13. College of Engineering, Pune Instrumentation Engineering 600646610 2119 97.46806010 14. Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute(VJTI), Matunga, Mumbai Electronics Engineering 301237610 2302 97.28562773 15. Sardar Patel College of Engineering, Andheri Mechanical Engineering 301461210 2381 97.21454610 16. College of Engineering, Pune Civil Engineering 600619110 2503 97.11600202 17. Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan's Sardar Patel Institute of Technology , Andheri, Mumbai Information Technology 321524610 2568 97.05085076 18. Veermata Jijabai Technological Institute(VJTI), Matunga, Mumbai Electrical Engineering 301229310 2690 96.66381126 Shri Vile Parle Kelvani Mandal's Dwarkadas J. -

Minutes-PNS-Med-29 January 2019 Annexurea.Xlsx

Admissions Regulating Authority, Mumbai ANNEXURE - A The Course/College/Institute wise details of admissions of admitted students admitted in Academic Year 2018-19 No. of No. of Student No. of No. of Sr. District Course Name College Code College Name Admitted Approved in Admissions Discrepancies No Name students previous Approved found Meeting B. SHRI SANT GAJANAN MAHARAJ 1 Engineering/B. '01011101' Buldhana 377 377 0 0 COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING Tech B. Prof. Ram Meghe Institute of 2 Engineering/B. '01011105' Technology & Research, Badnera- Amravati 575 574 0 0 Tech Amravati P. R. Pote (Patil) Education & Welfare B. Trust Group of Institutions, College of 3 Engineering/B. '01011107' Amravati 339 334 3 2 Engineering & Management, Tech Amravati B. Sipna College of Engineering & 4 Engineering/B. '01011114' Amravati 421 421 0 0 Technology, Amravati Tech B. Shri Shivaji Education Society 5 Engineering/B. '01011116' Amravati's College Of Engineering Akola 196 196 0 0 Tech And Technology Akola B. Babasaheb Naik College of 6 Engineering/B. '01011117' Yavatmal 100 100 0 0 Engineering, Pusad Tech B. ANURADHA ENGINEERING COLLEGE, 7 Engineering/B. '01011119' Buldhana 239 239 0 0 CHIKHLI Tech B. Jawaharlal Darda Institute of 8 Engineering/B. '01011120' Yavatmal 138 138 0 0 Engineering & Technology Tech B. H.V.P.M COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & 9 Engineering/B. '01011121' Amravati 126 126 0 0 TECHNOLOGY, AMRAVATI Tech B. Dr Rajendra Gode Institute of 10 Engineering/B. '01011123' Amravati 52 52 0 0 Technology & Research Amravati Tech B. Rajarshi Shahu College of 11 Engineering/B. '01011125' Buldhana 11 11 0 0 Engineering,Buldana Tech B. -

MAHARASHTRA ACT No. II of 2004 the MAHARASHTRA STATE

[2004 : Mah. II Maharashtra State Council for Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy Act, 2002 GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA LAW AND JUDICIARY DEPARTMENT MAHARASHTRA ACT No. II OF 2004 THE MAHARASHTRA STATE COUNCIL FOR OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY AND PHYSIOTHERAPY ACT, 2002. (As modified upto the 6th May 2019) PRINTED IN INDIA BY THE MANAGER, GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS, MUMBAI AND PUBLISHED BY THE DIRECTOR, GOVERNMENT PRINTING, STATIONERY AND PUBLICATIONS, MAHARASHTRA STATE, MUMBAI 400 004. 2019 [ Price : Rs. 69/- ] 2004 :: Mah.Mah. II] II] Maharashtra State Council for Occupational (i) Therapy and Physiotherapy Act, 2002 THE MAHARASHTRA STATE COUNCIL FOR OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY AND PHYSIOTHERAPY ACT, 2002. –––––––––––– CONTENTS PREAMBLE. SECTIONS. CHAPTER I PRELIMINARY. 1. Short title, extent and commencement. 2. Definitions. CHAPTER II CONSTITUTION OF THE COUNCIL. 3. Constitution and incorporation of a Council. 4. Term of office. 5. Casual vacancies. 6. Resignation. 7. Disqualification. 8. Meetings of Council. 9. Proccedings of meetings. 10. Executive Committee and other Committees. 11. Equivalence and Registration Committee. 12. Fees and allowance to members of Council, Executive Committee and Equivalence and Registration Committee. 13. Income and Expenditure of Council. 14. Appointment of Registrar, his duties and functions. 15. Other employees of Council. CHAPTER III FUNCTIONS OF THE COUNCIL. 16. Powers, duties and functions of Council. 17. Permission for establishment of new institutions, new course of study, etc. 18. Non-recognition of qualifications in certain cases. 19. Time for seeking permission for certain existing institutions. 20. Recognition of qualifications granted by Universities, etc., in India or abroad for occupational therapy or physio- therapy professionals. H 2446—1 (ii) Maharashtra State Council for Occupational [2004 : Mah. -

Sr.No Application Id Merit No Merit Marks Choice Code Allotted

LLB3 Admitted Candidate Ex-Serviceman Preferenc Merit Choice Code Seat Type Reporting CAP Sr.No Application Id Merit No Institute Name e No Marks Allotted Allotted Status Round Allotted Shri Swami Vivekananda Shikshan Sanstha, 1 L318143363 9174 62 12421001 ExServiceMan 1 Admitted 1 Kolhapur'S Law College, Osmanabad Shri Swami Vivekananda Shikshan Sanstha, 2 L318147805 20074 45 12421001 ExServiceMan 1 Admitted 1 Kolhapur'S Law College, Osmanabad Marathwada Shikshan Prasarak Mandal'S 3 L318157523 20619 44 12421002 Swatantrya Senani Ramrao Awargaonkar Law ExServiceMan 1 Admitted 1 College Beed PEOPLE'S EDUCATION SOCIETY, MUMBAI'S DR. 4 L318145864 13533 54 12421004 AMBEDKAR COLLEGE OF LAW, AURANGABAD ExServiceMan 1 Admitted 1 M.S PARAM POOJYA DR BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR SMARAK SAMITI, DEEKSHABHOOMI, NAGPUR'S 5 L318148973 11128 58 14421002 ExServiceMan 1 Admitted 1 DR AMBEDKAR COLLEGE, DEPARTMENT OF LAW, DEEKSHABHOOMI, NAGPUR Rashtrasant Tukdoji Maharaj Nagpur University, Nagpur'S Rashtrasant Tukdoji 6 L318144703 21297 42 14521001 ExServiceMan 1 Admitted 1 Maharaj Nagpur University's Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar College of Law, MainBranch Ngp Khandesh College Education Society, Jalgaon'S 7 L318152809 14748 52 16421001 ExServiceMan 1 Admitted 1 S.S.Maniyar Law College,Jalgaon. COUNCIL OF EDUCATIONS'S SHAHAJI LAW 8 L318150837 11385 58 18421002 ExServiceMan 1 Admitted 1 COLLEGE KOLHAPUR COUNCIL OF EDUCATIONS'S SHAHAJI LAW 9 L318161450 23781 35 18421002 ExServiceMan 1 Admitted 1 COLLEGE KOLHAPUR Bharati Vidyapeeth Pune'S Bharati 10 L318145775 9312 62 18421006 -

Workshop Attended Details Sr

Ramrao Adik Institute of Technology Nerul, Navi Mumbai Department of Instrumentation Engineering -Workshop Attended Details Sr. No. of Name of Faculty Title Date College Location No. days 10/05/2021 to 1 Dr. Bhawana Garg Python Programming 6 NITTTR, Chennai Chennai 15/05/2021 01/05/2021 to 2 Abhay Pakhare Canva Graphic Design 6 GrowMate New Delhi 06/05/2021 5G Design: From waveform generation to 3 Vivek Kadam 21-04-2021 1 MathWorks Webinars Online hardware implementation and verification Radar System Engineering: From 4 Vivek Kadam 20-04-2021 1 MathWorks Webinars Online Requirements to Deployment 19/04/2021 to 5 Abhay Pakhare Marketing Marerick 7 GrowMate New Delhi 25/04/2021 Workshop on Machine Learning, 15/04/2021 to 6 Dr. Bhawana Garg Department of computer Science & 2 SIRT, Bhopal Bhopal 16/04/2021 Engineering, SIRT, Bhopal 7 Vivek Kadam Avishkar Research Convention 2021 12-04-2021 1 University of Mumbai Mumbai Online Faculty Development Program on Karmayogi Engineering 8 Rakesh Borase the “Role of National Education 30-03-2021 1 Pandharpur College, Shelve Pandharpur Policy for National Development” AICTE-ATAL sponsored National Level Dr. Shirish S. Pravaranagar Rural Engg. 9 Webinar on National Education 26-03-2021 1 Loni Kulkarni College Policy(NEP)2020 Online Faculty Development Program on 24/03/2021 to Bajaj Institute of Technology, 10 Rakesh Borase “Role of Machine Learning & Artificial 2 Wardha 26/03/2021 Wardha Intelligence in Data Analytics” Online Faculty Development Program on Dr. Jayanand 24/03/2021 to Bajaj Institute of Technology, 11 “Role of Machine Learning & Artificial 2 Wardha Gawande 26/03/2021 Wardha Intelligence in Data Analytics” 09/03/2021 to 12 Dr.Sharad P Jadhav Control Systems and Application 5 NIT Sikkim Sikkim 13/03/2021 Woman as a Leader: Opportunities and 13 Shital Patil 08-03-2021 1 IEEE GRSS Bombay Mumbai Challenges Ramrao Adik Institute of Technology Nerul, Navi Mumbai Department of Instrumentation Engineering -Workshop Attended Details Sr. -

S.No APPLICATION NO PERMANENT ID INSTITUTE NAME 1 1

S.No APPLICATION NO PERMANENT ID INSTITUTE NAME 1 1-3326916946 1-10575231 A & M INSTITUTE OF COMPUTER & TECHNOLOGY 2 1-3327737172 1-11477181 A & M INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT AND TECHNOLOGY 3 1-3327282407 1-5305236 A M C . ENGINEERING COLLEGE 4 1-3328315783 1-405645191 A M K TECHNOLOGICAL POLYTECHNIC COLLEGE 5 1-3328468010 1-5724943 A P S COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING 6 1-3328103328 1-35645144 A R INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT & TECHNOLOGY 7 1-3325975729 1-10850261 A S N PHARMACY COLLEGE 8 1-3324978719 1-1505869571 A V S COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY 9 1-3328415137 1-2819951 A. J. INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT 10 1-3323813224 1-404292091 A. Y. DADABHAI TECHNICAL INSTITUTE 11 1-3326062501 1-399048571 A.A.N.M. & V.V.R.S.R. POLYTECHNIC 12 1-3323792931 1-7126777 A.D.PATEL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY 13 1-3322358483 1-425580821 A.G.PATIL POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE A.J.M.V.P.S., INSTITUTE OF HOTEL MANAGEMENT AND 14 1-3323649131 1-12373983 CATERING TECHNOLOGY 15 1-3325332643 1-5436091 A.K.R.G COLLEGE OF PHARMACY 16 1-3329444647 1-5220016 A.M.C. ENGINEERING COLLEGE A.M.REDDY MEMORIAL COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING& 17 1-3330451733 1-456138111 TECHNOLOGY A.N.A COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT 18 1-3330344524 1-7162981 STUDIES 19 1-3324867222 1-5473501 A.N.A COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT STUDIES 20 1-3326087215 1-463865741 A.P.GOVERNMENT INSTITUTE OF LEATHER TECHNOLOGY A.P.M.C. COLLEGE OF PHARMACEUTICAL EDUCATION AND 21 1-3324052284 1-4813295 RESEARCH 22 1-3324596267 1-452090031 A.R COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & TECHNOLOGY A.R.COLLEGE OF PHARMACY & G.H.PATEL INSTITUTE OF 23 1-3323963925 1-5747631 PHARMACY -

Maharashtra State Boatd of Sec & H.Sec Education Pune

MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 1 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC March-2018 Exam. Candidates passed College No. Name of the collegeStream Candidates Candidates Total Pass Registerd Appeared Pass UDISE No. Distin- Grade Grade Pass Percent ction I II Grade 11.01.001 ANNASAHEB AWATE COLLLAGE MANCHAR DIST PUNE SCIENCE 154 153 0 38 110 4 152 99.34 27250102212 ARTS 284 284 2 61 166 20 249 87.67 COMMERCE 215 215 35 106 54 11 206 95.81 TOTAL 653 652 37 205 330 35 607 93.09 11.01.002 M G JUNIOR COLLAGE, MANCHER, DIST PUNE SCIENCE 240 240 33 115 91 1 240 100.00 27250102207 TOTAL 240 240 33 115 91 1 240 100.00 11.01.003 JANATA VIDYAMANDIR JR OL OF COM,GHODEGAON SCIENCE 124 124 4 33 64 0 101 81.45 27250105704 AMBEGAON ARTS 107 107 1 22 64 6 93 86.91 COMMERCE 219 219 19 103 78 4 204 93.15 TOTAL 450 450 24 158 206 10 398 88.44 11.01.004 SHRI. SHIVAJI JUNIOR COL, DHAMANI AMBEGAON SCIENCE 45 45 0 5 34 2 41 91.11 27250100702 TOTAL 45 45 0 5 34 2 41 91.11 11.01.005 SHRI BHAIRAVNATH JR COL OF COM AVSARI KD SCIENCE 55 55 1 17 35 2 55 100.00 27250103503 AMBEGAON HSC.VOC 54 54 0 37 13 0 50 92.59 TOTAL 109 109 1 54 48 2 105 96.33 11.01.006 SHRI.BHAIRAVNATH VIDYADHAM HIGHER ARTS 27 27 0 4 13 2 19 70.37 27250105504 SEC.SCH,AMBEGAON COMMERCE 24 24 0 6 13 1 20 83.33 MAHARASHTRA STATE BOATD OF SEC & H.SEC EDUCATION PUNE PAGE : 2 College wise performance ofFresh Regular candidates for HSC March-2018 Exam. -

Member College List

Association Of The Managements Of Un-Aided Engineering Colleges (Mah.) Member Colleges DTE Phone No Fax No. Sr. Code Name of College & Address Name of Representative Mob. No. (STD) (STD) e-mail id No 1. 5107 Shrikrishna Educational & Cultural Mandal's Shri Gulabrao Prof. G.B.Deokar 9890179417 0257-2263036 0257-2261136 [email protected], Deokar College of Engineering, Gat no. 56, P. B. No. 113, Dr. A. J. Patil 9422780452 2264483/87 [email protected], Shirsoli Road, Jalgaon - 425 001. [email protected] , 2. 6649 TSSM’s, Bhivarabai Sawant College of Engineering And Dr. D. V. Jadhav 9422797509 020-64703673 / 020-24317389 [email protected], Research, S. No. 12/1/2 & 12/2/2, Narhe, Tal Haveli, Dist. Pune- 74 / 75 411048 3. 1265 Late Purushttam Hari (Ganesh) Patil Shikshan Sanshta, Mauli Dr. C.M.Jadhav 8308848692 07265-254462 07265-254462 [email protected], Group of Institution’s College of Engineering & Technology, 9423445548 254362 254362 [email protected], Khamgaon Road, Shegaon, Dist. Buldana-444203. Mr. D. P. Patil 9422182186 [email protected], 9011119191 4. 4190 M.D. Yergude Memorial Shikshan Prasarak Mandal's Shri Sai Shri. A. V. Yergude 9970854030 07175-230723, 07135-267370 [email protected], College Of Engineering & Technology, Near Village Lonara, Prof. K. A. Sikadar 267228, [email protected], Nagpur Road, Badravati. Chandrapur Pin 442902 267176, 5. 2516 International Centre of Excellence in Engineering & Dr. P. A. Deshmukh 9422209392 0240-2558101- 0240-2558111 [email protected], Management, Gut No. 4 Opp. Bajaj Auto Ltd. Infront of MIDC 10 filtration plant, Aurangabad-Pune High Way, Aurangabad- 431136 6. -

Semi-Fascism in Action Ashok Dhawale Introduction the Shiv Sena

The Marxist Volume: 16, No. 02 April-June 2000 The Shiv Sena: Semi-Fascism in Action Ashok Dhawale Introduction The Shiv Sena, during nearly three and a half decades of its existence, has always symbolised the semi-fascist face of reaction. Amongst all the regional parties that are today opportunistically supporting the BJP-led regime at the Centre, it is only the Shiv Sena (SS) that has a clear ideological affinity with the RSS-controlled Sangh Parivar. That is precisely why the SS has been the BJP's earliest and oldest political ally in the country. For the last 11 years since 1989, the two have had an unbroken alliance at both national and state levels. Despite rough patches, this alliance is set to continue for the near future. Although their interpretations may somewhat differ, the SS and the BJP share a common allegiance to the communal and fascistic concept of cultural nationalism and to the aim of achieving a "Hindu Rashtra". The rapid growth of the SS in Maharashtra since the mid-eighties is, in fact, closely linked to the parallel growth of the saffron brigade at the national level during the same period. One of the major reasons for thee success of the communal appeal, whether of the SS or the BJP, is of course the fertile soil provided by the deepening economic crisis resulting from the policies of successive Congress governments. Another important reason has been the ruling class tendency of compromising with the communal forces, at both national and state levels. In the case of the SS, as we shall see, this tendency has been exhibited with a vengeance. -

Vice-Chancellor

DR. UDHAV V. BHOSLE, Ph.D. (IIT Bombay) Vice-Chancellor Email: [email protected]; Career Highlights . Currently working as the Vice-Chancellor, Swami Ramanand Teerth Marathwada University, Nanded from 05th November, 2018. Member, Academic Council, University of Mumbai since August 2017. Worked as a Principal, MCT’s Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Technology (RGIT), Mumbai, from May 2007 to October 2018. Director (Technical): VDF and MCT, Latur from Jan 2009 to September 2010. Vice President (Technical), Latur from October 2010 to May 2012. Chairman, Board of Studies in Electronics & Telecommunication Engineering, University of Mumbai since September 2012. Visited United Kingdom during the week of 15th to 20th April 2012 as an Indian participant to participate biennial Ministerial UK-India Science and Innovation Council meeting on behalf of Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. Member Academic Council, University of Mumbai since September 2012. Member Faculty of Technology, University of Mumbai since September 2012 . Member Board of University Teaching and Research (BUTR), for the Faculty of Technology since September 2012 . Member Research and Recognition Committee (RRC committee) for Board of Studies in Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering September 2012. Member, Board of Studies in Electrical Engineering, University of Mumbai, from September 2005 to September 2010. Member, Board of Studies Electronics and Communication Engineering, Faculty of Technology, SNDT Women’s University Mumbai, since September 2013 . Consultant for IIP (Indian Intellectual Property) Services, USA, (July 2004 - August 2008) Specific Positions Held . Presiding Officer, Joint Entrance Examination: IIT-JEE, GATE, ISAT, ICRB . Convener and General Chair for International / National Conferences / Workshops organized at Mumbai . General Chair, Convener and Resource Person Session Chairs for IETE / IEEE International / National Conferences and Workshops held in India and abroad. -

Workshops Attended No

Ramrao Adik Institute of Technology Nerul, Navi Mumbai Workshops Attended No. of Sr. No. Name of Faculty Title Date College Location Days 1 Dr. Bhawana Garg Python Programming 10-05-2021 6 NITTTR, Chennai Chennai Truba Group of Institute, Attended workshop on “How to write and 2 Deepali Patil 06-05-2021 2 Conducted by Dr. Sunil Online publish” Goyal FDP on Research Methods in Vishwatmak Om Gurudev 3 Madhuri Chavan 02-05-2021 5 Online Science,Engineering & Technology(RMSET) COE, Shahapur FDP on Research Methods in Vishwatmak Om Gurudev 4 Priyanka Shingane 02-05-2021 5 Online Science,Engineering & Technology(RMSET) COE, Shahapur Department Of Mechanical Engineering, Attended FDP on “Research Methods in Vishwatmak Om Gurudev 5 Priyanka Shingane Science, Engineering & Technology 02-05-2021 5 Online College Of Engineering (RMSET)” Mohili-Aghai, Shahapur, Thane Conducted During 6 Abhay Pakhare Canva Graphic Design 01-05-2021 6 GrowMate New Delhi 5G Design: From waveform generation to 7 Vivek Kadam 21-04-2021 1 MathWorks Webinars Online hardware implementation and verification Radar System Engineering: From 8 Vivek Kadam 20-04-2021 1 MathWorks Webinars Online Requirements to Deployment 9 Abhay Pakhare Marketing Marerick 19-04-2021 7 GrowMate New Delhi Workshop on Machine Learning, Department 10 Dr. Bhawana Garg of computer Science & Engineering, SIRT, 15-04-2021 2 SIRT, Bhopal Bhopal Bhopal 11 Vivek Kadam Avishkar Research Convention 2021 12-04-2021 1 University of Mumbai Mumbai Vidyavardhka College of 12 Mrs. Swarupa Bodhe Intellectual Property Rights and Patents 08-04-2021 3 Engineering (VVCE) , Online Mysuru Ramrao Adik Institute of Technology Nerul, Navi Mumbai Workshops Attended No.