Investigation of Its Effectiveness As a Method of Whole Class Reading Comprehension Instruction at Key Stage Two

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Janet and John: Here We Go Free Download

JANET AND JOHN: HERE WE GO FREE DOWNLOAD Mabel O'Donnell,Rona Munro | 40 pages | 03 Sep 2007 | Summersdale Publishers | 9781840246131 | English | Chichester, United Kingdom Janet and John Series Toral Taank rated it it was amazing Nov 29, All of our paper waste is recycled and turned into corrugated cardboard. Doesn't post to Germany See details. Visit my eBay shop. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Shelves: beginner-readersfemale-author-or- illustrator. Hardcover40 pages. Reminiscing Read these as a child, Janet and John: Here We Go use with my Grandbabies X Previous image. Books by Mabel O'Donnell. No doubt, Janet and John: Here We Go critics will carp at the daringly minimalist plot and character de In a recent threadsome people stated their objections to literature which fails in its duty to be gender-balanced. Please enter a number less than or equal to Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Watch this item Unwatch. Novels portal Children's literature portal. Janet and John: Here We Go O'Donnell and Rona Munro. Ronne Randall. Learning to read. Inas part of a trend in publishing nostalgic facsimiles of old favourites, Summersdale Publishers reissued two of the original Janet and John books, Here We Go and Off to Play. Analytical phonics Basal reader Guided reading Independent reading Literature circle Phonics Reciprocal teaching Structured word inquiry Synthetic phonics Whole language. We offer great value books on a wide range of subjects and we have grown steadily to become one of the UK's leading retailers of second-hand books. -

Week 3 Resources, Comprehension

Meaning Skills PLC Week 3 Resources, Comprehension Resources Within in the Lesson Additional Reading Resources Additional Links and Websites **Chapter 7 of Applying **Inspire a Life of Reading: Lesson You can use the CCRS- Research in Reading Plans to Engage Adult Beginning Lexile Correlation chart to Instructions for Adults by Susan Readers by Cheryl Knight, help you know what level McShane Appalachian State University is best suited for your This chapter of McShane's book This manual includes activities in learners. focuses on the topic of the areas of assessment, comprehension. There are also phonemic awareness, word Lexile.com is a nice site a few sample activities for analysis, fluency, vocabulary, and fluency. comprehension. Activities are that you can paste or type complete with goals and a text into in order to get The National Reading Panel objectives, directions, handouts, the lexile level. Subgroup Report on Fluency game boards, and materials lists. This report contains an All activities are correlated with Here is a link for question executive summary from each reading competencies and are stems for all of the CCRS subgroup that introduces the appropriate for individuals, teams, reading anchors topic area, outlines the group's or large groups. For lesson plans methodology, and highlights the incorporating comprehension, see Watch this video from a questions and results from each p. 89-156; for lesson plans California adult reading subgroup. This is an excellent incorporating relia (i.e. use of real- class for an example of a resource for anyone who wishes life documents/contextualized think aloud integrated into to understand the science and lessons), see p. -

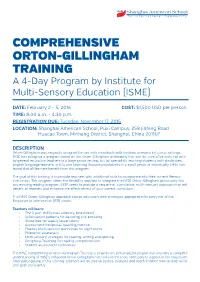

COMPREHENSIVE ORTON-GILLINGHAM TRAINING a 4-Day Program by Institute for Multi-Sensory Education (ISME)

Shanghai American School An International Community COMPREHENSIVE ORTON-GILLINGHAM TRAINING A 4-Day Program by Institute for Multi-Sensory Education (ISME) DATE: February 2 - 5, 2016 COST: $1,500 USD per person TIME: 8:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. REGISTRATION DUE: Tuesday, November 17, 2015 LOCATION: Shanghai American School, Puxi Campus, 258 Jinfeng Road Huacao Town, Minhang District, Shanghai, China 201107 DESCRIPTION Orton-Gillingham was originally designed for use with individuals with dyslexia primarily in tutorial settings. IMSE has designed a program based on the Orton-Gillingham philosophy that can be used effectively not only by general education teachers in a large group setting, but by specialists teaching students with disabilities, English language learners, or EAL and Learning Support populations in a small group or individually. IMSE has found that all learners benefit from this program. The goal of this training is to provide teachers with additional tools to incorporate into their current literacy instruction. This program offers the flexibility required to integrate the IMSE Orton-Gillingham philosophy into any existing reading program. IMSE seeks to provide a sequential, cumulative, multi-sensory approach that will benefit all learners and enhance the effectiveness of your current curriculum. The IMSE Orton-Gillingham approach equips educators with strategies appropriate for every tier of the Response to Intervention (RTI) model. Teachers will learn: • The 3-part drill (visual, auditory, kinesthetic) • Syllabication patterns for decoding and encoding • Guidelines for weekly lesson plans • Assessment Reciprocal Teaching method • Fluency Multi-sensory techniques for sight words • Phonemic awareness • Multi-sensory strategies for reading, writing and spelling • Reciprocal Teaching for reading comprehension • Student assessment techniques The IMSE Comprehensive Orton-Gillingham Training is a hands-on, personalized session that provides a complete understanding of IMSE’s enhanced Orton-Gillingham method and the tools necessary to apply it in the classroom. -

Literacy Perspectives

Vol.2, No.4 Winter/Spring 1998 CC-VI FORUM Comprehensive Regional Assistance Center Consortium—Region VI LITERACY PERSPECTIVES The Great Debate? From Walter Secada, Ph.D. Comprehensive Regional Assistance Center by Walter Secada, Ph.D. Consortium–RegionVI eading is one of the most important cur- As many of you know, riculum goals for the primary grades. A Minerva Coyne retired from R U. S. Department of Education prior- the University of Wisconsin– ity and national educational goal is that all stu- Madison this past October at dents read well by the end of third grade. In which time, I took over as the fourth grade, students are expected to “read to learn.” Reading instruction is heavily Regional Director. Minerva funded under Title I and other Titles of will be a very hard act to fol- Improving America’s Schools Act. low. She was truly committed How to best teach reading is one of the to improving our children’s most hotly debated topics among researchers, education and the professional educators, parents, and the general public. An lives of teachers. In addition, esprit simpliste has dominated the public policy debate, pitting phonics against whole language. she recruited a first rate staff and group of collabo- Such simplification makes for sharp debates rators to help the Center meet its mission. fraught with symbolic politics. Proponents of By way of self-introduction, I am a Professor of basic skills rally round the flag of phonics, Curriculum and Instruction at the University of painting supporters of whole language meth- Wisconsin–Madison. Many of you may remember me ods as lacking disciplinary values—both, educa- from when I directed a Multifunctional Resource tional and moral values it would seem, given INSIDE the shrill tenor of these debates. -

INFORMATION CAPSULE Research Services

Miami-Dade County Public Schools giving our students the world INFORMATION CAPSULE Research Services Vol. 0609 Christie Blazer, Supervisor March 2007 RECIPROCAL TEACHING At A Glance Reciprocal teaching is an instructional approach designed to increase students’ reading comprehension at all grade levels and in all subject areas. Students are taught cognitive strategies that help them construct meaning from text and simultaneously monitor their reading comprehension. This Information Capsule summarizes reciprocal teaching’s basic principles, implementation steps, and four comprehension strategies. Issues to consider when implementing reciprocal teaching are discussed, including how to teach the strategies, what grade levels and types of students benefit from reciprocal teaching, and optimum group size. Research on the impact of reciprocal teaching on students’ reading comprehension is reviewed and a brief summary of Miami-Dade County Public Schools’ use of reciprocal teaching is provided. Little progress has been made nationwide toward improving students’ reading skills during the past decade, as evidenced by minimal improvements in reading scores on the Nation’s Report Card, the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). The table below shows that the 2005 average NAEP grade 4 reading scale score was one point higher than the 2003 average score and two points higher than the 1992 average score (on a 500-point scale). In eighth grade, the 2005 average reading score was one point lower than the 2003 average score and two points higher than the 1992 average score. Grades 4 and 8 NAEP Reading Scale Scores, 1992, 2003, and 2005 300 275 260 263 262 Grade 8 250 225 217 218 219 Grade 4 200 175 1992 2003 2005 Source: National Center for Education Statistics, 2005. -

The Use of Using Reciprocal Teaching Technique in Reading Comprehension for Junior High School Students

THE USE OF USING RECIPROCAL TEACHING TECHNIQUE IN READING COMPREHENSION FOR JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS Emi Sabbara Graduate Program in ELT, Universitas Negeri Malang [email protected] Abstract: Reading skill is one of the important aspects in teaching English. It is undeniable that competent writers can develop after becoming competent readers. This study reports the importance of using reciprocal teaching technique especially in reading comprehension for junior high school students. Reciprocal teaching technique is a cooperative strategy where in this technique the students work as a group to comprehend the text to training the students to get the same perspective. There are four step that used in Reciprocal Teaching Technique namely: Summarizing, Questioning, Clarifying and Predicting. By knowing the importance of this technique, it is expected that teacher consider the implementation if this strategy in order to help their students comprehend the text. Keywords: Reciprocal Teaching, Reading Comprehension, Junior High School. INTRODUCTION Reading is one of skills that must be concerned by the students in learning English. Reading is an active activity. Through reading the students can interact with the text to understand the text. In reading activity there are two aspects that can be engaged: expressing the words and comprehending the substance of the text. By comprehending the reading text, the students can add and improve their knowledge,or information stated implicitly in the text. Smith and Robinson who stated “reading comprehension means understanding, evaluating, and utilizing and ideas gained through an interaction between reader and author”. Furthermore Paris, and Hamilton (2004: 321) point out: Understanding the meaning of the printed words and the text is the core function of literacy that enables people to communicate message across time and distance, express themselves beyond gesture and create and share ideas. -

Reading in the Twentieth Century. INSTITUTION Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, Ann Arbor, MI

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 479 530 CS 512 338 AUTHOR Pearson, P. David TITLE Reading in the Twentieth Century. INSTITUTION Center for the Improvement of Early Reading Achievement, Ann Arbor, MI. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 2000-08-00 NOTE 46p.; CIERA Archive #01-08. CONTRACT R305R70004 AVAILABLE FROM CIERA/University of Michigan, 610 E. University Ave., 1600 SEB, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1259. Tel: 734-647-6940; Fax: 734- 763 -1229. For full text: http://www.ciera.org/library/archive/ 2001-08/0108pdp.pdf. PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070). Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Educational History; *Educational Practices; Futures (of Society); Instructional Materials; *Reading Instruction; *Reading Processes; *Reading Research; Reading Skills; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS *Reading Theories ABSTRACT This paper discusses reading instruction in the 20th century. The paper begins with a tour of the historical pathways that have led people, at the century's end, to the "rocky and highly contested terrain educators currently occupy in reading pedagogy." After the author/educator unfolds his version of a map of that terrain in the paper, he speculates about pedagogical journeys that lie ahead in a new century and a new millennium. Although the focus is reading pedagogy, the paper seeks to connect the pedagogy to the broader scholarly ideas of each period. According to the paper, developments in reading pedagogy over the last century suggest that it is most useful to divide the century into thirds, roughly 1900-1935, 1935- 1970, and 1970-2000. The paper states that, as a guide in constructing a map of past and present, a legend is needed, a common set of criteria for examining ideas and practices in each period--several candidates suggest themselves, such as the dominant materials used by teachers in each period and the dominant pedagogical practices. -

Reciprocal Teaching Adapted for Kindergarten Students

PAMELA ANN MYERS The Princess Storyteller, Clara Clarifier, Quincy Questioner, and the Wizard: Reciprocal teaching adapted for kindergarten students Reciprocal-teaching strategies were used in a reciprocal-teaching strategies for kindergarten stu- dents. They had been skeptical, believing that kindergarten class to teach comprehension 5-year-olds were too young for such a sophisticat- through interactive read-alouds. ed learning strategy. However, it became evident to me, while listening to my students’ responses, s the school day began, Oscar (all names that my colleagues had been wrong. Adapting are pseudonyms), a shy second-language reciprocal-teaching strategies for kindergarten stu- Alearner, came up to me and told me he had dents had been extremely successful. been thinking about the book I had read the day be- fore. He mentioned that he had not known why Miss Nelson, the main character, was missing and A new focus that he had a “Clara Clarifier” question to ask me. He said he hadn’t understood why Detective At the beginning of that school year, the teach- McSmogg was now looking for Viola Swamp at ers at my school decided to focus the school plan the end of the story. I was very surprised because I on reading comprehension. We were concerned had never experienced a kindergartner asking me to that, while a large number of students were able to explain something he did not understand the day decode text successfully, they were not always able after I read a story. Other students were listening, to understand what they were reading. This con- and before I had a chance to answer, Jesse, a stu- cern is shared by many, including the National dent with great difficulty expressing his ideas, said Reading Panel (National Institute of Child Health to Oscar, “But it’s a joke, because Miss Nelson is and Human Development, 2000). -

Dyslexia Dyslexia

Dyslexia 1. In 1877, Berlin coined the term “dyslexia,” which was another name for word- blindness in adults, or what others referred to more accurately as “alexia” (an acquired inability to read as a result of brain damage). 2. In 1925, Samuel Orton wrote the first report on the clinical features of dyslexia in children. 3. In 1963, Samuel A. Kirk introduced the term “learning disability” at a national conference on behalf of frustrated parents who could not get funding for their dyslexic children, because there was no funding category for this yet. 4. In 1970, a neurologist named Critchley gave a good basic definition of dyslexia: “…a disorder manifested by difficulty in learning to read despite conventional instruction, adequate intelligence, and socio-cultural opportunity. It is dependent upon fundamental cognitive disabilities which are frequently of constitutional origin.” Later on, he expanded his definition and called the condition “developmental dyslexia.” 5. The 1994 DSM-IV Criteria for Reading Disorder (dyslexia): a. Reading achievement, as measured by an individually administered standardized test of reading accuracy or comprehension, is substantially below that expected given the person’s chronological age, measured intelligence, and age-appropriate education. b. The disturbance interferes with academic achievement or activities of daily living that require reading skills. c. If a sensory deficit is present, the learning difficulties are in excess of those usually associates with it. 6. Dyslexia afflicts approximately 3 percent of the school-age population, and about 5 percent of the entire U.S. population. 7. Dyslexia affects equal numbers of males and females. 8. A “dyslexic” individual typically has very poor decoding, word recognition, and spelling, with somewhat better reading comprehension skills. -

Nrc on the Gifted G/T and Talented

THE NATIONAL RESEARCH CENTER NRC ON THE GIFTED G/T AND TALENTED University of Connecticut University of Virginia Yale University The Schoolwide Enrichment Model Reading Study Sally M. Reis Rebecca D. Eckert Fredric J. Schreiber Joan Jacobs Christine Briggs E. Jean Gubbins Michael Coyne Lisa Muller University of Connecticut Storrs, Connecticut September 2005 RM05214 The Schoolwide Enrichment Model Reading Study Sally M. Reis Rebecca D. Eckert Fredric J. Schreiber Joan Jacobs Christine Briggs E. Jean Gubbins Michael Coyne Lisa Muller University of Connecticut Storrs, Connecticut September 2005 RM05214 THE NATIONAL RESEARCH CENTER ON THE GIFTED AND TALENTED The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented (NRC/GT) is funded under the Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Students Education Act, Institute of Education Sciences, United States Department of Education. The Directorate of the NRC/GT serves as an administrative and a research unit and is located at the University of Connecticut. The participating universities include the University of Virginia and Yale University, as well as a research unit at the University of Connecticut. University of Connecticut Dr. Joseph S. Renzulli, Director Dr. E. Jean Gubbins, Associate Director Dr. Sally M. Reis, Associate Director University of Virginia Dr. Carolyn M. Callahan, Associate Director Yale University Dr. Robert J. Sternberg, Associate Director Copies of this report are available from: NRC/GT University of Connecticut 2131 Hillside Road Unit 3007 Storrs, CT 06269-3007 Visit us on the web at: www.gifted.uconn.edu The work reported herein was supported under the Educational Research and Development Centers Program, PR/Award Number R206R000001, as administered by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. -

A Modest Proposal for Improving the Education of Reading Teachers

Hl- I L L I N 0 I S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Technical Report No. 487 A MODEST PROPOSAL FOR IMPROVING THE EDUCATION OF READING TEACHERS Richard C. Anderson Bonnie B. Armbruster Mary Roe University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign November 1989 Center for the Study of Reading TECHNICAL k, REPORTS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN 174 Children's Research Center 51 Gerty Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF READING Technical Report No. 487 A MODEST PROPOSAL FOR IMPROVING THE EDUCATION OF READING TEACHERS Richard C. Anderson Bonnie B. Armbruster Mary Roe University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign November 1989 University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 51 Gerty Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820 The work upon which this publication was based was supported in part by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and by the Office of Educational Research and Improvement under Cooperative Agreement No. G0087-C1001-89 with the Reading Research and Education Center. The publication does not necessarily reflect the views of the agencies supporting the research. EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD 1989-90 James Armstrong Jihn-Chang Jehng Linda Asmussen Robert T. Jimenez Gerald Arnold Bonnie M. Kerr Yahaya Bello Paul W. Kerr Diane Bottomley Juan Moran Catherine Burnham Keisuke Ohtsuka Candace Clark Kathy Meyer Reimer Michelle Commeyras Hua Shu John M. Consalvi Anne Stallman Christopher Currie Marty Waggoner Irene-Anna Diakidoy Janelle Weinzierl Barbara Hancin Pamela Winsor Michael J. Jacobson Marsha Wise MANAGING EDITOR Fran Lehr MANUSCRIPT PRODUCTION ASSISTANTS Delores Plowman Debra Gough Anderson, Armbruster, & Roe A Modest Proposal - 1 Abstract The usual preservice teacher education program suffers from several shortcomings. -

The Effectiveness of the Word Study Program on Teaching Elementary Students with Learning Disabilities

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Theses and Dissertations 6-30-2016 The effectiveness of the Word Study program on teaching elementary students with learning disabilities Catherine Marie DiPierro Rowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd Part of the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation DiPierro, Catherine Marie, "The effectiveness of the Word Study program on teaching elementary students with learning disabilities" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1732. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/1732 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECTIVENESS OF THE WORD STUDY PROGRAM ON TEACHING ELEMENTARY STUDENTS WITH LEARNING DISABILITIES by Catherine M. DiPierro A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Interdisciplinary and Inclusive Education College of Education In partial fulfillment of the requirement For the degree of Master of Arts in Learning Disabilities at Rowan University May 4, 2016 Thesis Chair: Joy Xin, Ph.D. ©2016 Catherine M. DiPierro Dedication I would like to dedicate this manuscript to my parents, Tommaso and Elizabeth DiPierro. Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to all the people that have helped me through this educational journey. I have gained skills and knowledge that I will carry with me into the next chapter of my life. I look forward to the challenges and triumphs that await me and am fully prepared to address them. I would like to thank my parents, especially my mother for her unconditional support.