Page Proof Instructions and Queries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How America Lost Its Secrets: Edward Snowden, the Man and the Theft. by Edward Jay Epstein. New York, N.Y.; Alfred A. Knopf, 2017

Journal of Strategic Security Volume 10 Number 1 Article 9 How America Lost its Secrets: Edward Snowden, The Man and The Theft. By Edward Jay Epstein. New York, N.Y.; Alfred A. Knopf, 2017. Millard E. Moon, Ed.D., Colonel (ret), U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss pp. 143-147 Recommended Citation Moon, Ed.D.,, Millard E. Colonel (ret),. "How America Lost its Secrets: Edward Snowden, The Man and The Theft. By Edward Jay Epstein. New York, N.Y.; Alfred A. Knopf, 2017.." Journal of Strategic Security 10, no. 1 (2017) : 143-147. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5038/1944-0472.10.1.1590 Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/vol10/iss1/9 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Strategic Security by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How America Lost its Secrets: Edward Snowden, The Man and The Theft. By Edward Jay Epstein. New York, N.Y.; Alfred A. Knopf, 2017. This book review is available in Journal of Strategic Security: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/jss/ vol10/iss1/9 Moon, Ed.D.,: How America Lost its Secrets How America Lost its Secrets: Edward Snowden, The Man and The Theft. By Edward Jay Epstein. New York, N.Y.; Alfred A. Knopf, 2017. ISBN: 9780451494566. Photographs. Notes. Selected Bibliography. Index. Pp. 350. $27.95. Edward Jay Epstein is a well known and respected investigative journalist. -

Edward Snowden

wanted”, and the more he learned about NSA’s ubiquitous international surveillance pro- The man who grammes, the more troubled he became. “A sys- tem of global mass surveillance,” he realised, pro- exposed the duces “a permanent record of everyone’s life”, and indeed that was the intelligence agencies’ pro- watchers fessed goal. “The value of any piece of information is only known when you can connect it with some- David J. Garrow thing else that arrives at a future point in time,” CIA chief technical officer Gus Hunt explained in early Dark Mirror: 2013. “Since you can’t connect dots you don’t Edward Snowden dward snowden revealed him- have, it drives us into a mode of, we fundamentally and the American self to the world, via a Guardian try to collect everything and hang onto it forever.” Surveillance State web-video, on 9 June 2013, four By that time, Snowden had resolved to act, but by Barton Gellman days after the Guardian, and then his initial anonymous messages to radical journal- The Bodley Head, the Washington Post, first reported ist Glenn Greenwald went unanswered. Progres- £20 on the astonishing treasure trove of top-secret US sive filmmaker Laura Poitras did respond, and she Eintelligence community documents they had in turn contacted both former Washington Post Permanent Record been given by the 29-year-old computer systems reporter Bart Gellman, a well-known national se- by Edward Snowden engineer who worked at the National Security curity journalist, and Greenwald. By mid-May Poi- Macmillan, £20 Agency’s (NSA) Hawaii listening post. -

Snowdenshailene Woodley ©2016 Sacha, Inc

PATHÉ PRÉSENTE EN ASSOCIATION AVEC WILD BUNCH, VENDIAN ENTERTAINMENT ET TG MEDIA JOSEPH GORDON-LEVITT SNOWDENSHAILENE WOODLEY ©2016 SACHA, INC. TOUS DROITS RÉSERVÉS © CRÉDITS NON CONTRACTUELS INC. ©2016 SACHA, UN FILM DE OLIVER STONE PATHÉ PRÉSENTE EN ASSOCIATION AVEC WILD BUNCH ENTERTAINMENT VENDIAN ENTERTAINMENT TG MEDIA UNE PRODUCTION MORITZ BORMAN SNOWDEN UN FILM DE OLIVER STONE JOSEPH GORDON-LEVITT SHAILENE WOODLEY MELISSA LEO ZACHARY QUINTO TOM WILKINSON UN FILM PRODUIT PAR MORITZ BORMAN & ERIC KOPELOFF D’APRÈS L’OUVRAGE DE LUKE HARDING & LE ROMAN DE ANATOLY KUCHERENA SCÉNARIO DE KIERAN FITZGERALD & OLIVER STONE SORTIE LE MARDI 1ER NOVEMBRE DURÉE : 2H14 www.snowden-lefilm.com DISTRIBUTION PRESSE PATHÉ DISTRIBUTION MICHÈLE ABITBOL-LASRY 2, RUE LAMENNAIS − 75008 PARIS SÉVERINE LAJARRIGE TÉL. : 01 71 72 30 00 184, BD HAUSSMANN − 75008 PARIS FAX : 01 71 72 33 10 TÉL. : 01 45 62 45 62 [email protected] / [email protected] DOSSIER DE PRESSE ET PHOTOS TÉLÉCHARGEABLES SUR WWW.PATHEFILMS.COM À elle seule, l’Histoire fait d’Edward Snowden une figure marquante. Ses révélations en 2013 – une démarche qui en Amérique vaut le qualificatif de « lanceur d’alerte » à son auteur s’il s’agit d’un fonctionnaire du gouvernement – ont déclenché une prise de conscience générale du fait que les nouvelles technologies avaient atteint des niveaux d’omniscience inédits jusqu’alors – du fait que « ils », les Yeux et les Oreilles du gouvernement, pouvaient voir et entendre tout ce que nous, vous, moi, considérons comme privé. Quelles que soient vos convictions ou réactions à propos de la démarche de Snowden, il est indéniable qu’il a tenté de nous alerter sur l’illégalité des agissements de ce nouvel État de Sécurité Nationale, dont la surveillance de masse de sa propre population. -

October 2016 the Head of the Charles Continued on Page 24

The RegisterRegister ForumForum Established 1891 Vol. 129, No. 2 Cambridge Rindge and Latin School October 2016 The Head of the Charles Continued on page 24 Three Rindge boats raced in the 52nd Head of the Charles; the Varsity Boys boats came in 19th and 66th and the Varsity Girls came in 22nd place. Photo Credit: Cam Poklop For Rindge, It’s No Contest Cambodian Genocide In RF Mock Election Hillary Wins Handily Survivor Speaks at CRLS nominee for president. ge students are not a fan eight years old to fight in By By All together, 14.4% of of the Twenty-Second Am- a war. In the middle of the Diego Lasarte Kiana Laws students, unprompted, re- mendment, as 1.8% of the war, Pond fled to the jungle Register Forum Register Forum Staff fused to pick one of the four student body—fifth place— Editor-in-Chief and later found himself in a major candidates or to ab- wrote in President Obama, In 1975, after the Viet- Thai refugee camp. Soon he After surveying al- stain and instead wrote in a wanting a third term for the nam war, the Khmer Rouge was found by Peter Pond, an most one fourth of CRLS candidate of their choosing. sitting president. took over Cambodia. They American man who later ad- students, teachers, and After Senator Sanders, However, President promised to bring peace opted him and brought him staff, the Register Forum is Republican nominee Don- Obama was not the only back to their country, but to America. prepared to announce that ald Trump and Libertarian write-in ineligible for the instead they starved and In America, he went Democratic nominee Sec- nominee Governor Gary office of the presidency: re- abused millions of Cambo- to highschool, but things retary Clinton has cently martyered dians, wiping out almost all were still very difficult for won the Rindge gorilla Harambe of their music him. -

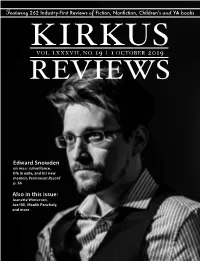

Edward Snowden Also in This Issue

Featuring 262 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVII, NO. 19 | 1 OCTOBER 2019 REVIEWS Edward Snowden on mass surveillance, life in exile, and his new memoir, Permanent Record p. 56 Also in this issue: Jeanette Winterson, Joe Hill, Maulik Pancholy, and more from the editor’s desk: Chairman Stories for Days HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] Photo courtesy John Paraskevas courtesy Photo Lisa Lucas, executive director of the National Book Foundation, recently Editor-in-Chief TOM BEER told her Twitter followers that she has been reading a short story a day and [email protected] Vice President of Marketing that “it has been a deeply satisfying little project.” Lisa’s tweet reminded SARAH KALINA me of a truth I often lose sight of: You’re not required to read a story col- [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor lection cover to cover, all at once, as if it were a novel. As a result, I’ve ERIC LIEBETRAU [email protected] started hopscotching among stories by old favorites such as Lorrie Moore, Fiction Editor LAURIE MUCHNICK Deborah Eisenberg, and Alice Munro. I’ve also turned my attention to [email protected] Children’s Editor some collections that are new this fall. Here are three: VICKY SMITH Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of Nancy Hale edited by Lauren [email protected] Young Adult Editor Tom Beer Groff (Library of America, Oct. 1). Like so many neglected women writers of LAURA SIMEON [email protected] short fiction from the middle of the 20th century—Maeve Brennan, Edith Templeton, Mary Ladd Editor at Large MEGAN LABRISE Gavell—Hale isn’t widely read today and is ripe for rediscovery. -

Snowden Un Film De Oliver Stone ©2016 Sacha, Inc

SECCIÓN OFICIAL FUERA DE CONCURSO PATHÉ PRESENTA EN ASOCIACIÓN CON WILD BUNCH, VENDIAN ENTERTAINMENT Y TG MEDIA JOSEPH GORDON-LEVITT SHAILENE WOODLEY SNOWDEN UN FILM DE OLIVER STONE ©2016 SACHA, INC. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. INC. ©2016 SACHA, Open Road Films y Endgame presentan Borman/Kopeloff Production En asociación con Wild Bunch y TG Media Una película de Oliver Stone Joseph Gordon-Levitt Shailene Woodley Melissa Leo Zachary Quinto Tom Wilkinson Rhys Ifans Nicholas Cage Ben Schnetzer Keith Stanfield Productores ejecutivos: Bahman Naraghi, José Ibáñez, Max Arvelaiz, Tom Ortenberg, Peter Lawson, James Stern, Douglas Hansen, Christopher Woodrow, and Michael Bassick Producida por Moritz Borman, Eric Kopeloff, Phillip Schulz-Deyle, and Fernando Sulchin Guion de Kieran Fitzgerald and Oliver Stone Dirigida por Oliver Stone CONTACTOS DE PRENSA Vértigo Films Teléfono: 915 240 819 Fernando Lueches [email protected] Borja Moráis [email protected] Para descargar materiales: http://www.vertigofilms.es/prensa/snowden/ Del tres veces ganador del Oscar Oliver Stone, Snowden es una mirada personal sobre una de las figuras más controvertidas del siglo XXI, el hombre responsable de lo que ha sido descrito como el mayor atentado con- tra la seguridad en la historia del NSA de EE.UU. En 2013, Edward Snowden (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) deja silenciosamente su trabajo en la NSA y vuela a Hong Kong para reunirse con los periodistas Glenn Greenwald (Zachary Quinto) y Ewen MacAskill (Tom Wilkinson), y la cineasta Laura Poitras (Melissa Leo) para revelar los enormes programas de vigilancia cibernética del gobierno de Estados Unidos. Un contratista de seguridad con conocimientos de programación asombrosos, Ed, ha descu- bierto que una montaña virtual de datos está siendo recogida de todas las formas de comunicación digital - no sólo de gobiernos y grupos terroris- tas extranjeros, sino también de ciudadanos estadounidenses. -

Secret Government Searches and Digital Civil Liberties

Secret Government Searches and Digital Civil Liberties By Neil Richards* Perhaps surprisingly, the most compelling moment in Oliver Stone’s “Snowden” biopic is the sex scene. Halfway through this movie about government surveillance and whistleblowing, the audience is shown a graphic and seemingly gratuitous sexual encounter involving Edward Snowden (played by Joseph Gordon Levitt) and his girlfriend Lindsay Mills (played by Shailene Woodley). In the midst of their passion, Snowden’s eyes rest on Lindsay’s open laptop, the empty eye of its camera gazing towards them. In a flash, he recalls an earlier event in which NSA contractors hacked laptop cameras to secretly spy on surveillance subjects in real time. Edward and Lindsay’s mood was ruined, to say the least, by the prospect of government agents secretly watching their intimate activities. The scene evokes George Orwell’s famous warning about telescreens, the omnipresent surveillance devices in Big Brother’s Oceania, by which the Thought Police could secretly watch anyone at any time.1 It also has grounding in reality. The use of millions of hacked webcams as monitoring devices was a program known as “Optic Nerve,” which was part of the Snowden revelations.2 Another program leaked by Snowden involved the surveillance of the pornography preferences of jihadi radicalizers (including at least one “U.S. person”), with the intention being the exposure of their sexual fantasies to discredit them in the Muslim world.3 Snowden himself famously appeared on John Oliver’s HBO show “Last Week Tonight,” humorously but effectively reducing unchecked government surveillance to the basic proposition that secret surveillance allowed the government, among other things, to “get your dick pics.”4 * Thomas & Karole Green Professor of Law, Washington University School of Law; Affiliate Scholar, The Center for Internet and Society at Stanford Law School; Affiliated Fellow, Yale Information Society Project. -

SNOWDEN – Film at CONCA VERDE on 27.02.17 Talk by Joel ORMSBY

SNOWDEN – Film at CONCA VERDE on 27.02.17 Talk by Joel ORMSBY Have you ever imagined you live in a world where the government are watching your every movement? You are about to watch a film which discusses the reality of this idea. The film is based on the real story of Edward Snowden who went from obscurity to being a globally known figure overnight, and will go down in history as one of America’s most famous whistle-blowers. A ‘whistle-blower’ is someone who tells people in authority or the public about dishonest or illegal practices about a government or company. Edward was a 29-year-old former technical assistant for the CIA and former contractor for the USA government. Whilst working for them he copied and later leaked highly classified information from within the NSA (the National Security Agency for electronic espionage). This info revealed massive covert global surveillance operations ran by the American government in cooperation with many European governments. The leaked info caused a worldwide scandal with many countries reacting furiously over the alleged US spying activities. Cast and Crew The film was directed by Academy Award®-winning director Oliver Stone, who produced Platoon, Born on the Fourth of July, Wall Street and JFK. The film was written by Stone himself and Kieran Fitzgerald, based on the books The Snowden Files by Luke Harding and Time of the Octopus by Anatoly Kucherena. The film stars Joseph Gordon Levitt who started in American TV comedies such as Roseanne and 3 rd Rock from the Sun. -

Wer Ist Edward Snowden?

Filmpädagogische Begleitmaterialien SNOWDEN, USA/Deutschland 2016, 135 Min. Kin start: 22. Se#te$%er 2016, Uni&ersum 'ilm (egie Oli&e! St ne D!eh%uch Kie!an Fit*ge!ald, Oli&e! St ne, +!ei nach dem Sach%uch „-e Sn .den Files/ v n Lu1e Ha!ding und dem R man „3ime of the Oct pus“ v n Anat l4 Kuche!ena Ka$e!a Anth n4 D d Mantle Schni5 Alex Ma!7ue*, Lee Pe!c4 Musi1 9!aig A!mst! ng, Adam Pete!s 8! du*enten Mo!it* B !man, E!ic K pel ;, Philip Schul*<De4le, Fe!nand Sulichin Da!stelle!/innen = seph G !d n<0e&i5 (Ed.a!d Sn .den@, Shailene W dle4 (0indsa4 Mills), Ben Schnet*e! (>a%!iel S l@, Nic las Cage (Han1 F !!este!@, (h4s Ifans (9 !%in OB:!ian@, Sc 5 East. d (3!e& ! James), Zacha!4 Dint (>lenn G!een.ald@, Melissa Le (0au!a P it!as@, T m Wil1ins n (E.en MacAskill@ u. a. 'SK a% 6 Jah!en 8Eda) gische Alte!se$#+ehlun) a% 15 Jah!enF a% 9. Klasse -emen H%e!.achung, Idealismus, Ve!ant. !tung, F!eiheit, Techn l gie, 8 liti1, Sel%st%estimmung, Heldentum, Medien An1nJpfungspun1te fJ! SchulKEche! Deutsch, Englisch, Ethi1/(eligi n, S *ial1unde, Kunst Impressum He!ausge%e!" :ildnach.eise" 3ext und K n*ept" Uni&e!sum Film G$%2 Uni&e!sum Film G$%2 Stefan Stile5 Neuma!1te! St!. 2L stile5 Ofilme<sch ene!<sehen.de L16M3 München ....uni&e!sumfilm.de 2 Unter Beobachtung A used t w !1 fo! the go&e!nment. -

America's War on Whistleblowers

DePauw University Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University Communication & Theatre Faculty Publications Communication & Theatre 8-2020 Violence, Intimidation and Incarceration: America’s War on Whistleblowers Kevin Howley DePauw University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.depauw.edu/commtheatre_facpubs Part of the Discourse and Text Linguistics Commons Recommended Citation Howley, Kevin. “Violence, Intimidation and Incarceration: America’s War on Whistleblowers.” Journal for Discourse Studies, 7.3 (2019): 265-284. NOTE: Due to pandemic-related delays, this article was published in August 2020. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication & Theatre at Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication & Theatre Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly and Creative Work from DePauw University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Violence, Intimidation and Incarceration: America’s War on Whistleblowers 265 Kevin Howley Violence, Intimidation and Incarceration: America’s War on Whistleblowers Zusammenfassung: Viel wurde bereits über die autoritären Tendenzen von US-Präsident Donald Trump gesagt. Trumps hetzerische Rhetorik und drakonische Politik enthüllen die Gewalt, welche in dem aktuellen politischen Diskurs und in den gegenwärtigen Machtverhältnissen eingebettet ist. Wäh- rend Trumps verbale Übergriffe auf Journalist*innen gut dokumentiert sind und weithin diskutiert wer- den, werden seine Bemühungen – und auch die seines unmittelbaren Vorgängers Barack Obama – Whistleblower*innen zum Schweigen zu bringen, weitaus weniger untersucht. Ausgehend von Diskurs- theorie und Diskursanalyse untersucht dieser Beitrag die Erfahrung von drei prominenten Leaker*innen sowie die epistemische Gewalt, die Amerikas Krieg gegen Whistleblower untermauert. -

EDWARD SNOWDEN Quick Facts

EDWARD SNOWDEN Quick Facts Name Edward Snowden Birth Date June 21, 1983 (age 31) Education University of Liverpool, Anne Arundel Community College Place of Birth North Carolina AKA Verax Edward Snowden Full Name Edward Joseph Snowden Zodiac Sign Cancer Edward Snowden may be a former National Security Agency contractor WHO created headlines in 2013 once he leaked high secret data regarding United States intelligence agency police investigation activities. quotes “I don't need to measure in an exceedingly society that will these kind of things ... I don't need to measure in an exceedingly world wherever everything I do and say is recorded. that's not one thing i'm willing to support or live below.” —Edward Snowden Synopsis Born in North Carolina in 1983, Edward Snowden worked for the National Security Agency through contractor Booz Allen within the NSA's island workplace. once solely 3 months, Snowden began assembling classified documents concerning United States intelligence agency domestic police investigation practices, that he found distressful. once Snowden fled to port, China, newspapers began printing the documents that he had leaked to them, several of them particularization invasive spying practices against americans. With the U.S. charging Snowden below the spying Act however several teams line him a hero, Snowden remains in Russia, with the U.S. government functioning on surrender. Early Years Edward Snowden was born in North Carolina on midsummer, 1983, and grew up in Elizabeth town. His mother works for the court in Baltimore (the family touched to Ellicott town, Maryland, once Snowden was young) as chief deputy clerk for administration and knowledge technology. -

The Snowden Saga

SPECIAL REPORT THE SNOWDEN SAGA: A SHADOWLAND OF SECRETS AND LIGHT Whether hero or traitor, former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden is the most important whistle-blower of modern times, one whose disclosures will reverberate for decades to come. With extensive input from Snowden himself, Suzanna Andrews, Bryan Burrough, and Sarah Ellison have the spy-novel-worthy tale of how a geeky dropout from the Maryland suburbs found himself alone and terrified in a Hong Kong hotel room, spilling America’s most carefully guarded secrets to the world. BY BRYAN BURROUGH, SARAH ELLISON & SUZANNA ANDREWS ILLUSTRATIONS BY SEAN MCCABE MAY 2014 THE SENDER Edward Joseph Snowden, whose theft of top-secret documents from the National Security Agency represents the most serious intelligence breach in U.S. history. In the background, the headquarters of the N.S.A., Fort Meade, Maryland. “When you are in a position of privileged access,” Snowden has said, “you see things that may be disturbing. Over time that awareness of wrongdoing sort of builds up.” Illustration by Sean McCabe. fter setting up his personal security systems and piling pillows against the door so no one in the hallway could eavesdrop, he sat on the bed, anxious and alone, in a Hong Kong hotel room. He was 29 years old that night, May 24, 2013, but he looked much younger, thin and pale, like a college kid, in his blue jeans and white T-shirt. Someone who talked to him later described him as “terrified,” and it’s easy to believe. He was Awalking away from everything he had ever known, his career, his girlfriend, his entire life, and now it appeared that his plan might fall through.