Historic Environment Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

Issues and Options Topic Papers

Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council Local Development Framework Joint Core Strategy and Development Management Policies Development Plan Document Issues and Options Topic Papers February 2012 Strategic Planning Tameside MBC Room 5.16, Council Offices Wellington Road Ashton-under-Lyne OL6 6DL Tel: 0161 342 3346 Email: [email protected] For a summary of this document in Gujurati, Bengali or Urdu please contact 0161 342 8355 It can also be provided in large print or audio formats Local Development Framework – Core Strategy Issues and Options Discussion Paper Topic Paper 1 – Housing 1.00 Background • Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing (PPS3) • Regional Spatial Strategy North West • Planning for Growth, March 2011 • Manchester Independent Economic Review (MIER) • Tameside Strategic Housing Land Availability Assessment (SHLAA) • Tameside Strategic Housing Market Assessment 2008 (SHMA) • Tameside Unitary Development Plan 2004 • Tameside Housing Strategy 2010-2016 • Tameside Sustainable Community Strategy 2009-2019 • Gypsy and Traveller Accommodation Assessment • Tameside Residential Design Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) 1.01 The Tameside Housing Strategy 2010-2016 is underpinned by a range of studies and evidence based reports that have been produced to respond to housing need at a local level as well as reflecting the broader national and regional housing agenda. 2.00 National Policy 2.01 At the national level Planning Policy Statement 3: Housing (PPS3) sets out the planning policy framework for delivering the Government's housing objectives setting out policies, procedures and standards which Local Planning Authorities must adhere to and use to guide local policy and decisions. 2.02 The principle aim of PPS3 is to increase housing delivery through a more responsive approach to local land supply, supporting the Government’s goal to ensure that everyone has the opportunity of living in decent home, which they can afford, in a community where they want to live. -

Davenport Green to Ardwick

High Speed Two Phase 2b ww.hs2.org.uk October 2018 Working Draft Environmental Statement High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report | Volume 2 | MA07 MA07: Davenport Green to Ardwick High Speed Two (HS2) Limited Two Snowhill, Snow Hill Queensway, Birmingham B4 6GA Freephone: 08081 434 434 Minicom: 08081 456 472 Email: [email protected] H10 hs2.org.uk October 2018 High Speed Rail (Crewe to Manchester and West Midlands to Leeds) Working Draft Environmental Statement Volume 2: Community Area report MA07: Davenport Green to Ardwick H10 hs2.org.uk High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has been tasked by the Department for Transport (DfT) with managing the delivery of a new national high speed rail network. It is a non-departmental public body wholly owned by the DfT. High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, Two Snowhill Snow Hill Queensway Birmingham B4 6GA Telephone: 08081 434 434 General email enquiries: [email protected] Website: www.hs2.org.uk A report prepared for High Speed Two (HS2) Limited: High Speed Two (HS2) Limited has actively considered the needs of blind and partially sighted people in accessing this document. The text will be made available in full on the HS2 website. The text may be freely downloaded and translated by individuals or organisations for conversion into other accessible formats. If you have other needs in this regard please contact High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. © High Speed Two (HS2) Limited, 2018, except where otherwise stated. Copyright in the typographical arrangement rests with High Speed Two (HS2) Limited. -

Investment Programme 2 3

TRANSPORT FOR THE Investment Programme 2 3 Introduction Developing the Investment Programme Transport for the North’s (TfN’s) Strategic Transport Plan sets out an ambitious vision for how transport can support transformational, inclusive growth in the This initial version of the Investment Programme builds North of England through to 2050. This accompanying Investment Programme on the strategic rail and road schemes previously comprises TfN’s advice to the Government on the long-term, multimodal priorities announced, and draws on the Integrated and Smart Travel programme, the Long Term Rail Strategy, the Strategic for enhanced pan-Northern connectivity. Outline Business Case for Northern Powerhouse Rail, the Major Road Network for the North, and the work done to date on the Strategic Development Corridors identified in the Strategic Transport Plan. It is important to consider future investments and decisions As with the Strategic Transport Plan, the Investment strategically, ensuring that infrastructure not only provides Programme has a horizon year of 2050, to align with the the basics for the economy, but also actively supports the Northern Powerhouse Independent Economic Review, long-term national interests. The Strategic Transport Plan and sets out TfN’s view of the appropriate pipeline of and this Investment Programme do just that, by ensuring investment in strategic transport to deliver those plans. that the North’s existing and future economic assets and This will enable TfN and its Partners to secure funding and clusters are better connected. delivery of the right schemes at the right time. The successful delivery of the Investment Programme will The Investment Programme aims to provide greater require continuous close working with TfN’s Constituent certainty for Local Transport and Highway Authorities Authority Partners, the national Delivery Partners (Highways to deliver complementary investment. -

Minor Eye Conditions Service (MECS) Tameside and Glossop Pharmacies That Are Currently Providing Mecs

Minor Eye Conditions Service (MECS) Tameside and Glossop Pharmacies that are currently providing MECs Name Address Telephone 169 Mossley Road, Ashton-under-Lyne, Lancashire, OL6 Adams Pharmacy 6NE 0161 339 8889 Stalybridge Resource Centre, 2 Waterloo Road, Stalybridge. Adams Pharmacy SK15 2AU 0161 303 8599 Alipharma Ltd Thornley House Med Ctr) 11 Thornley Street, Hyde SK14 1JY 0161 351 1386 Asda Cavendish Street, Ashton Under Lyne, OL6 7DP 0161 342 6610 Asda Water Street, Hyde, Cheshire, SK14 1BD 0161 882 5700 22 Stockport Road, Ashton-Under-Lyne, Lancashire, OL7 Ashton Pharmacy 0LB 0161 330 4389 Ashton Primary Care Centre Pharmacy 193 Old Street, Ashton-Under-Lyne, Lancashire, OL6 7SR 0161 820 8281 Audenshaw Pharmacy 3 Chapel Street, Audenshaw, Manchester, M34 5DE 0161 320 9123 Boots 116-118 Station Road, Hadfield, Glossop SK13 1AJ 01457 853635 Hattersley Health Centre, Hattersley Road East, Hattersley, Boots Hyde SK14 3EH 0161 368 8498 Boots 72 Market Street, Droylsden, Manchester M43 6DE 0161 370 1626 Boots 30 Concorde Way, Dukinfield, Cheshire SK16 4DB 0161 330 3586 Boots 173 Mossley Road, Ashton-Under-Lyne OL6 6NE 0161 330 1303 Boots 1-3 Bow Street, Ashton-Under-Lyne OL6 6BU 0161 330 1746 Boots UK Ltd 15-17 Staveleigh Way, Ashton-Under-Lyne OL6 7JL 0161 308 2326 Boots UK Ltd 19 High Street West, Glossop, Derbyshire SK13 8AL 01457 852011 Boots UK Ltd 1A Market Place, Hyde, Cheshire SK14 2LX 0161 368 2249 Boots UK Ltd 33 Queens Walk, Droylsden, Manchester M43 7AD 0161 370 1402 Crown Point North, Retail Park, Ashton Road, Denton M34 -

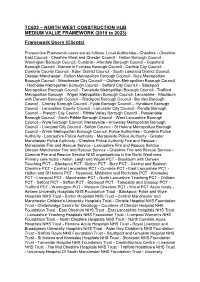

Framework Users (Clients)

TC622 – NORTH WEST CONSTRUCTION HUB MEDIUM VALUE FRAMEWORK (2019 to 2023) Framework Users (Clients) Prospective Framework users are as follows: Local Authorities - Cheshire - Cheshire East Council - Cheshire West and Chester Council - Halton Borough Council - Warrington Borough Council; Cumbria - Allerdale Borough Council - Copeland Borough Council - Barrow in Furness Borough Council - Carlisle City Council - Cumbria County Council - Eden District Council - South Lakeland District Council; Greater Manchester - Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council - Bury Metropolitan Borough Council - Manchester City Council – Oldham Metropolitan Borough Council - Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council - Salford City Council – Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council - Tameside Metropolitan Borough Council - Trafford Metropolitan Borough - Wigan Metropolitan Borough Council; Lancashire - Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council – Blackpool Borough Council - Burnley Borough Council - Chorley Borough Council - Fylde Borough Council – Hyndburn Borough Council - Lancashire County Council - Lancaster City Council - Pendle Borough Council – Preston City Council - Ribble Valley Borough Council - Rossendale Borough Council - South Ribble Borough Council - West Lancashire Borough Council - Wyre Borough Council; Merseyside - Knowsley Metropolitan Borough Council - Liverpool City Council - Sefton Council - St Helens Metropolitan Borough Council - Wirral Metropolitan Borough Council; Police Authorities - Cumbria Police Authority - Lancashire Police Authority - Merseyside -

SPOC | Central Pennines Strategic

This document is Not for Publication - On-going Research Central Pennines: Strategic Development Corridor - Strategic Programme Outline Case Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................. 7 Strategic Dimension ........................................................................... 15 2 Introduction ................................................................................ 15 3 The Case for Change .................................................................... 26 4 The Need for Intervention ........................................................... 66 5 Wider Context ............................................................................. 70 6 Option Assessment Process ......................................................... 72 7 Strategic Dimension Summary ..................................................... 87 Economic Dimension........................................................................... 89 8 Introduction ................................................................................ 89 9 Approach to Cost Estimation ........................................................ 95 10 Quantified SDC Programme Impacts ............................................ 98 11 Economy Impacts ...................................................................... 104 12 Environment Impacts ................................................................ 106 13 Social Impacts........................................................................... 111 14 -

Proposed Free School – Opening September 2018 Report on Section 10 Public Consultation 9Th June 2017-8Th September 2017

Laurus Ryecroft Proposed free school – opening September 2018 Report on Section 10 public consultation th th 9 June 2017-8 September 2017 laurustrust.co.uk 4 October 17 Page 1 of 21 Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 3 The proposer group ............................................................................................................... 4 Initial phase ........................................................................................................................... 4 Statutory consultation ............................................................................................................ 6 Stakeholders ......................................................................................................................... 7 Statutory consultation results and responses ........................................................................ 9 Other responses to the consultation .................................................................................... 18 Conclusion and next steps .................................................................................................. 21 Appendices: Appendix 1 – Section 10 consultation information booklet Appendix 2 – Consultation questionnaire Appendix 3 – Promotional material Appendix 4 – Stakeholders laurustrust.co.uk 4 October 17 Page 2 of 21 Executive summary Laurus Ryecroft is a non-selective, non-denominational 11-18 secondary school in the pre-opening -

72, Carlton Road, Ashton-Under-Lyne, Tameside, Greater Manchester, OL6 8PZ Offers Over £150,000

EPC Awaited 72, Carlton Road, Ashton-under-Lyne, Tameside, Greater Manchester, OL6 8PZ Offers Over £150,000 Two double bedroom period terraced. Enjoying a convenient location close to Ashton Town Centre with excellent shopping facilities including Ashton Moss retail park, Ladysmith shopping centre and Snipe retail park. A short distance to both the Metrolink and Train station with routes to Manchester and other surrounding areas. Serviced by the M60 motorway network for those needing to commute to other cities and located close to Tameside general hospital and excellent local schooling. This handsome period property is full of character, traditional features and has a hearty/homely feeling. Deceptive from the front as internally you will find a brilliant space and large rooms, high ceilings and an airy bright arrangement. Comprising of; a traditional entrance hallway leading to both the front lounge and the rear dining room, patio doors leading out into the courtyard to enjoy the sunshine, a galley kitchen with fitted wall and base units, two very large double bedrooms which could easily be turned into three, a family bathroom with three piece suite and a small garden to the front. A lovely front facing aspect over the green makes this house even more appealing. This property is sure to attract early attention so don't delay and call the team to secure your viewing today. Viewing arrangement by appointment 0161 339 5499 [email protected] Bridgfords, 6 Fletcher Street, Ashton Under Lyne, OL6 6BY https://www.bridgfords.co.uk Interested parties should satisfy themselves, by inspection or otherwise as to the accuracy of the description given and any floor plans shown in these property details. -

Ppg17 Sports Facility Assessment

TAMESIDE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL PPG17 SPORTS FACILITY ASSESSMENT AUGUST 2010 Integrity, Innovation, Inspiration 1-2 Frecheville Court off Knowsley Street Bury BL9 0UF T 0161 764 7040 F 0161 764 7490 E [email protected] www.kkp.co.uk Quality assurance Name Date Report origination H. Jones Feb 2010 Quality control C Fallon Feb 2010 Final approval C Fallon August 2010 TAMESIDE METROPOLITAN BOROUGH COUNCIL PPG17 SPORTS FACILITY ASSESSMENT CONTENTS GLOSSARY........................................................................................................................ 5 PART 1: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 6 Study limitations.............................................................................................................. 8 PART 2: CONTEXT............................................................................................................ 9 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 9 National context .............................................................................................................. 9 Regional context ........................................................................................................... 13 Local context................................................................................................................. 13 PART 3: PLAYING PITCH ASSESSMENT METHODOLOGY........................................ -

The London Gazette, Issue 26813, Page

206 THE LONDON GAZETTE, JANUARY 12, 1897. DISEASES OF ANIMALS ACTS, 1894 AND 1896 (continued). Middlesex.—An Area in the county of Middlesex Essex.—A district or area comprising the petty comprising the township of Uxbridge, and the sessional divisions of South Hiuckford, Chelms- parishes of Hillingdon East, Hillingdon West, ford, Dengie, and Rochford, in the county of Cowley, Yiewsley. Hayes, Norwood, and Han- Essex, and also comprising the borough of well (except Han well detached) (17 Novem- Southend-on-Sea (16 November, 1896). ber, 1896). Hampshire.—A district or area comprising the Norfolk.—An Area comprising the petty sessional petty sessional divisions of Petersfield (except divisions of Freebridge Marshland, and Clack- the parish of Bramshott detached), Droxford, close, in the counly of Norfolk (16 November, and Southampton, in the county of Southampton, 1896). and also comprising the borough of Southampton Staffordshire.—(1.) An Area comprising the (3 December, 1896). municipal borough of Tamworth, in the county Huntingdonshire.—A district or area in the of Stafford (23 November, 1896). county of Huntingdon comprising the petty (2.) An Area comprising the parishes or sessional divisions of Hurstingstcne, Toseland townships of Rushton Spencer, Rushton James, (except the parish of Swineshead detached and Heatori, Rudyard, Horton and Horton Hay, the portion of the parish of Tetworth detached), Leek (Urban), Lowe, Endon and Stanley, Leightoiistone, and Ramsey (except the portion- Longsdon, Cheddleton, Consall, and Ipstones, of the parish of Ramsey detached) (21 Novem- in the county of Stafford (23 November 1896). ber, 1896). Isle of Ely and Norfolk.—A district or area com- Warwickshire.—(1.) An Area comprising the prising the petty sessional divisions of Wisbech parishes of St. -

The London Gazette, November 25, 1892

THE LONDON GAZETTE, NOVEMBER 25, 1892. the Borough of Stalybridge, and terminating in Corporation to acquire by compulsion or agree- the :township of Dukinfield, in the parish of ment rights or easements in, over, under, or Stockport, in the county of Chester, in a field connected with lands, houses, and buildings. numbered on the ordnance map, scale l-2500th To empower the Corporation to stop up, alter, for the parish of Stockport, at a point 150 yards, or divert, whether temporarily or permanently, measuring in a south-westerly direction from all such rords, streets, highways, brooks, streams, the centre of the bridge carrying the Manchester, canals, subways, sewers, pipes, aqueducts, rail- Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway over the ways, and telegraphs as it may be necessary to occupation road used for the accommodation of stop up, alter, or divert for the purposes of the the Plantation Farm, and which said sewer is intended Act. intended to pass from, in, through or into the To empower the Corporation to purchase and said townships and parishes of Ashton-under- take by compulsion or agreement all or some of Lyne, and of Dukinfield and Stockport. the following lands, and to use such lands for A Sewer (No. 1) wholly situate in the said the purpose of receiving, storing, disinfecting, or township and parish of Ashton-under-Lyne, distributing sewage, and to empower the Cor- commencing in Corkland-street, at the southern poration to erect, make, and lay down on such end thereof, and terminating by a junction with lauds all necessary and proper tanks, buildings, the intended intercepting sewer at a point in engines, pumps, sewers, drains, channels, and Whitelands-road, 100 yards west of the centre of other sewage works.