Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sexism in Advertising

Sexism in Advertising A Qualitative Study of the Influence on Consumer Attitudes Towards Companies MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Degree of Master of Science in Business and Economics AUTHOR: Hanna Andersson & Emilia Schytt JÖNKÖPING May 2017 Master Thesis in Business Administration Title: Sexism in Advertising: A Qualitative Study of the Influence on Consumer Attitudes Towards Companies Authors: Hanna Andersson and Emilia Schytt Tutor: Tomas Müllern Date: 2017-05-22 Key terms: Women in Advertising, Sexist Advertising, Congruity, Incongruity, Gender Differences, Consumer Attitudes. Background: Advertising is one of the most powerful influences on consumer attitudes, and for several decades, sexism in advertising and its affects on society has been a current topic. Even though the increased importance of equality in today’s society, sexism are still commonly depicted in advertising. How women are portrayed in advertising has been suggested to affect women’s perceived role in society and increased stereotypical roles defining how they should act and behave. Purpose: The study will seek insight in consumer attitudes formed by sexist advertising, and understanding of the difference between congruent sexist ads and incongruent sexist ads. The purpose of this study is to understand how sexist advertising influence consumer attitudes of a company. The ambition is to contribute to a greater understanding of sexist advertisements’ impact on companies. Method: An interpretive approach was adopted in order to gain deep insight and understanding in the subject. An exploratory study was conducted in the form of qualitative two-part interviews. Through a convenience sampling, 50 respondents were selected, divided into 25 females and 25 males in the ages of 20-35. -

Positioning Guide

Positioning: How Advertising Shapes Perception © 2004 Learning Seed Voice 800.634.4941 Fax 800.998.0854 E-mail [email protected] www.learningseed.com Summary Positioning: How Advertising Shapes Perception uses ideas from advertising, psychology, and mass communication to explore methods marketers use to shape consumer perception. Traditional persuasion methods are less effective in a society besieged by thousands of advertising messages daily. Advertising today often does not attempt to change minds, it seldom demonstrates why one brand is superior, nor does it construct logical arguments to motivate a purchase. Increasingly, advertising is more about positioning than persuasion. The traditional approach to teaching “the power of advertising” is to borrow ideas from propaganda such as the bandwagon technique, testimonials, and glittering generalities. Although these ideas still work, they ignore the drastic changes in advertising in the past ten years. Advertisers recognize that “changing minds” is both very difficult and not really necessary. To position a product to fit the consumer’s existing mind set is easier than changing a mind. Consumers today see advertising more as entertainment or even “art” than as persuasion. Positioning means nothing less than controlling how people see. The word “position” refers to a place the product occupies in the consumer’s mind. Positioning attempts to shape perception instead of directly changing minds. Positioning works because it overcomes our resistance to advertising. The harder an ad tries to force its way into the prospect’s mind, the more defensive the consumers become. Nobody likes to be told how to think. As a result, advertising is used to position instead of to persuade. -

Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

CHAPTER 9 Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning 9.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES When you have read this chapter you should be able to understand: (a) the nature and purpose of market segmentation; (b) the contribution of segmentation to effective marketing planning; (c) how markets can be segmented, and the criteria that need to be applied if segmentation is to prove cost-effective; (d) how product positioning follows from the segmentation process; (e) the bases by which products and brands can be positioned effectively. 9.2 INTRODUCTION In Chapters 5 –7 we focused on approaches to environmental, customer and competitor analysis, and the frameworks within which strategic mar- keting planning can best take place. Against this background we now turn to the question of market segmentation, and to the ways in which compa- nies need to position themselves in order to maximize their competitive advantage and serve their target markets in the most effective manner. It does need to be recognized, however, that for many organizations the stra- tegic issues of market segmentation, market targeting and positioning often take on only a minimal role. A variety of authors (see, for example, Saunders, 1987; Solomon et al., 2006) have all pointed to the way in which approaches to segmentation are often poorly thought out and then poorly implemented. Strategic Marketing Planning Copyright © 2009 Colin Gilligan and Richard M.S. Wilson. All rights reserved. 339 340 CHAPTER 9: Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning There are several possible reasons for views such as these, although, in the case of companies with a broadly reactive culture, it is often due largely to a degree of organizational inertia, which leads to the fi rm being content to stay in the same sector of the market for some considerable time. -

Competitive Analysis for a Growth Mindset

Competitive Analysis for a Growth Mindset Competitive Analysis for a Growth Mindset 1 Building a Growth Marketing Plan with Competitive Analysis: What Every Marketer Needs to Know Building and scaling marketing is hard work—from creating content to launching campaigns to analyzing and optimizing channels, there’s work to be done in every corner. While you’re trying to attract and engage your personas, it turns out, so are your competitors. Your competitors’ content, campaigns, and solutions are affecting how those target customers perceive you, and affect the impact of all of your marketing efforts. So how do you fuel your growth in light of all of the market changes around you? The key is understanding and analyzing your competitors’ moves and incorporating those lessons into your growth marketing plans. In this guide, we’ll dive into the how-to of completing a full competitive analysis, outline a methodology for incorporating competitive analysis into each area of your marketing plan, and dig into the details of turning competitive insights into marketing wins across product marketing, demand gen, content marketing, and branding and PR. Businesses report having an average of 25 competitors in their market, and 87% say that their market has become more competitive in the last three years. Crayon State of Competitive Intelligence 2019 Competitive Analysis for a Growth Mindset 2 What is Competitive Analysis? Competitive analysis is the process of studying your market landscape and each player in that market to uncover patterns and trends. In a business context, this means digging deep into the solutions, marketing, teams, and more of each of your rivals to understand their strengths, weaknesses, and strategies in order to determine your own plan of action to grow and win. -

Michael E. Porter

COMPETITIVE Books by Michael E. Porter The Competitive Advantage of Nations ( 1990) Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Pe$ormance (1985) Cases in Competitive Strategy (1982) Competition in the Open Economy (with R.E. Caves and A.M. Spence) (1 980) Interbrand Choice, Strategy and Bilateral Market Power (1976) COMPETITIVE STRATEGY Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors With a new Introduction Michael E. Porter THE FREE PRESS THE FREE PRESS A Division of Simon & Schuster Inc 1230 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10020 Copyright O 1980 by The Free Press New introduction copyright O 1998 by The Free Press All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. First Free Press Edition 1980 THE FREE PRESS and colophon are trademarks of Simon & Schuster Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America 62 61 60 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, Michael E. Competitive strategy: techniques for analyzing industries and competitors: with a new introduction1 Michael E. Porter. p. cm. .. Originallypublished: New York: Free Press, c I980 Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Competition. 2. Industrial management. I. Title. HD4 1 .P67 1998 658dc21 98-9580 CIP ISBN 0-684-84148-7 Contents Introduction Preface xvii Introduction, 1980 xxi PART I General Analytical Techniques CHAPTER 1 THE STRUCTURAL ANALYSIS OF INDUSTRIES 3 Structural Determinants of the Intensity of Competition 5 Structural Analysis and Competitive Strategy 29 Structural Analysis -

Product Positioning Strategy in Marketing Management

Journal of Naval Science and Engineering 2009, Vol. 5 , No 2, pp. 98-110 PRODUCT POSITIONING STRATEGY IN MARKETING MANAGEMENT Ph.D. Mustafa KARADENIZ, Nav. Cdr. Turkish Naval Academy Director of Naval Science and Engineering Institute Tuzla, Istanbul, Turkiye [email protected] Abstract In today’s globalizing and continuously developing economies, the competition among enterprises grows quickly, the market share gets narrower; and in order to gain new markets, companies are trying to create superiority over their rivals by positioning new products aimed at consumer behaviors and perceptions. In this sense, product positioning strategy in marketing management has emerged and now companies conduct studies on this strategy. In this research, product positioning strategy is emphasized and related examples are given. PAZARLAMA YÖNETİMİNDE ÜRÜN KONUMLADIRMA STRATEJİSİ Özetçe Küreselleşen ve sürekli gelişen günümüz ekonomilerinde işletmeler arasında rekabet hızla artmakta Pazar payı daralmakta ve şirketler yeni pazarlar elde etmek için tüketici davranış ve algılamalarına yönelik yeni ürünler konumlandırarak rakiplerine üstünlük ve farkındalık yaratmaya çalışmaktadırlar. Bu kapsamda, pazarlama yönetiminde ürün konumlandırma stratejisi ortaya çıkmış olup halen şirketler bu strateji üzerine çalışmalar yapmaktadırlar. Bu araştırmada ürün konumlandırma stratejisi üzerinde durulmuş ve konuya ilişkin örnekler verilmiştir. Keywords : Marketing, Product Positioning, Brand Anahtar Kelimeler : Pazarlama, Ürün Konumlandırma, Marka 98 Mustafa KARADENIZ -

5 Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

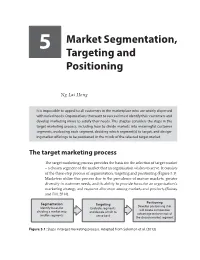

Market Segmentation, 5 Targeting and Positioning Ng Lai Hong It is impossible to appeal to all customers in the marketplace who are widely dispersed with varied needs. Organisations that want to succeed must identify their customers and develop marketing mixes to satisfy their needs. This chapter considers the steps in the target marketing process, including how to divide markets into meaningful customer segments, evaluating each segment, deciding which segment(s) to target, and design- ing market offerings to be positioned in the minds of the selected target market. The target marketing process The target marketing process provides the basis for the selection of target market – a chosen segment of the market that an organisation wishes to serve. It consists 84 Fundamentalsof the three-step of Marketing process of segmentation, targeting and positioning (Figure 5.1). Marketers utilise this process due to the prevalence of mature markets, greater diversity in customer needs, and its ability to provide focus for an organisation’s marketing strategy and resource allocation among markets and products (Baines and Fill, 2014). Segmentation Positioning Targeting Develop positioning that Identify bases for Evaluate segments will create competitive dividing a market into and decide which to advantage in the minds of smaller segments serve best the chosen market segment Figure 5.1: Steps in target marketing process. Adapted from Solomon et al. (2013). 86 Fundamentals of Marketing The benefits of this process include the following: Understanding customers’ needs. The target marketing process provides a basis for understanding customers’ needs by grouping customers with similar characteristics together and for the selection of target market. -

The Importance and Level of Adaptation of STP Strategies for Growth in Foreign Markets: in the Case of Soft Drinks Company

Asian Journal of Economics, Business and Accounting 19(2): 13-23, 2020; Article no.AJEBA.61566 ISSN: 2456-639X The Importance and Level of Adaptation of STP Strategies for Growth in Foreign Markets: In the Case of Soft Drinks Company Md. Mahathy Hasan Jewel1 and Kh Khaled Kalam2* 1Department of Marketing, Jagannath University, Bangladesh. 2Economics and Business School, Shandong Xiehe University, China. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between both authors. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/AJEBA/2020/v19i230299 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Fang Xiang, University of International and Business Economics, China. (2) Dr. Chan Sok Gee, University of Malaya, Malaysia. Reviewers: (1) Getie Andualem Imiru, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. (2) Najah Hassan Salamah, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia. (3) Huseyin Altay, Inonu University, Turkey. (4) Ibajanaishisha M. Kharbudon, Fazl Ali College, India. (5) M. Beulah Viji Christiana, Anna University, India. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle4.com/review-history/61566 Received 10 August 2020 Accepted 15 October 2020 Case Study Published 12 November 2020 ABSTRACT STP denotes Segmentation, Targeting, and Positioning. This study's main purpose is to demonstrate the STP concept's understanding and its importance in the success or failure of a Soft Drinks company. Examines the competitive role of Soft Drinks in the global soft beverage industry. Since they operate in over 200 countries, they have a simple choice as to whether their products are standardized worldwide and whether they can benefit from economies of magnitude and adapt their products to a given market. -

Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning By Mark Anthony Camilleri 1, PhD (Edinburgh) How to Cite : Camilleri, M. A. (2018). Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning. In Travel Marketing, Tourism Economics and the Airline Product (Chapter 4, pp. 69-83). Springer, Cham, Switzerland. Abstract Businesses may not be in a position to satisfy all of their customers, every time. It may prove difficult to meet the exact requirements of each individual customer. People do not have identical preferences, so rarely does one product completely satisfy everyone. Therefore, many companies may usually adopt a strategy that is known as target marketing. This strategy involves dividing the market into segments and developing products or services to these segments. A target marketing strategy is focused on the customers’ needs and wants. Hence, a prerequisite for the development of this customer-centric strategy is the specification of the target markets that the companies will attempt to serve. The marketing managers who may consider using target marketing will usually break the market down into groups (segments). Then they target the most profitable ones. They may adapt their marketing mix elements, including; products, prices, channels, and promotional tactics to suit the requirements of individual groups of consumers. In sum, this chapter explains the three stages of target marketing, including; market segmentation (ii) market targeting and (iii) market positioning. 4.1 Introduction Target marketing involves the identification of the most profitable market segments. Therefore, businesses may decide to focus on just one or a few of these segments. They may develop products or services to satisfy each selected segment. -

SEX in ADVERTISING … ONLY on MARS and NOT on VENUS? Darren W

54 GfK MIR / Vol. 3, No. 1, 2011 / Flashlight SEX IN ADVERTISING … ONLY ON MARS AND NOT ON VENUS? Darren W. Dahl, Kathleen D. Vohs and Jaideep Sengupta THE AUTHORS In an effort to cut through the tremendous clutter that ex- phasizes physical gratifi cation and views sex as an end ists in today’s advertising space, marketers have resorted in itself. In contrast, women tend to adopt a relationship- Darren W. Dahl, Sauder School to increasingly radical tactics to capture consumer atten- based orientation to sexuality, an approach that empha- of Business, University of tion. One such popular tactic uses explicit sexual images in sizes the importance of intimacy and commitment in a British Columbia, Canada, [email protected] advertising, even when the sexual image has little relevance sexual relationship. to the advertised product. For example, a recent print ad Kathleen D. Vohs, Carlson campaign for Toyo Tires showed a nude female model The premise that women and men have different mo- School of Management, crouched on all fours with the tag-line “Tires that Fit You”. tives regarding sex receives theoretical backing from University of Minnesota, USA, both evolutionary and socialization models of human be- [email protected] Although such gratuitous use of sex in advertising un- havior. Briefl y, an evolutionary view of sexual motives is Jaideep Sengupta, School of doubtedly succeeds in capturing attention, one may based on the model of differential parental investment, Business and Management, question whether evaluative reactions are favorable which argues that because human females must invest Hong Kong University of Science among different segments of consumers. -

Strategic Analysis Tools

Topic Gateway Series Strategic Analysis Tools Strategic Analysis Tools Topic Gateway Series No. 34 1 Prepared by Jim Downey and Technical Information Service October 2007 Topic Gateway Series Strategic Analysis Tools About Topic Gateways Topic Gateways are intended as a refresher or introduction to topics of interest to CIMA members. They include a basic definition, a brief overview and a fuller explanation of practical application. Finally they signpost some further resources for detailed understanding and research. Topic Gateways are available electronically to CIMA Members only in the CPD Centre on the CIMA website, along with a number of electronic resources. About the Technical Information Service CIMA supports its members and students with its Technical Information Service (TIS) for their work and CPD needs. Our information specialists and accounting specialists work closely together to identify or create authoritative resources to help members resolve their work related information needs. Additionally, our accounting specialists can help CIMA members and students with the interpretation of guidance on financial reporting, financial management and performance management, as defined in the CIMA Official Terminology 2005 edition. CIMA members and students should sign into My CIMA to access these services and resources. The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants 26 Chapter Street London SW1P 4NP United Kingdom T. +44 (0)20 7663 5441 F. +44 (0)20 7663 5442 E. [email protected] www.cimaglobal.com 2 Topic Gateway Series Strategic -

THE ROLE of POSITIONING in STRATEGIC BRAND MANAGEMENT – CASE of HOME APPLIANCE MARKET Lhotáková, M & Olšanová, K

G.J. C.M.P., Vol. 2(1) 2013:71-81 ISSN 2319 – 7285 THE ROLE OF POSITIONING IN STRATEGIC BRAND MANAGEMENT – CASE OF HOME APPLIANCE MARKET Lhotáková, M & Olšanová, K. Department of International Trade, University of Economics, Prague, Czech Republic. Abstract With growing competitiveness in the national as well as international markets, brands have increasing importance in consumer decision making process. Brands help consumers to choose products that satisfy their needs, fit their emotions and help them demonstrate their place in the society. Current financial crises proved that strong brands can do well even in bad times. Global brands ranked at the top of the most valued world´s brands put a lot of efforts in development of the right positioning, keeping it up-to-date and consistent across all brand´s activities. Positioning is broadly used tool of brand development but deep analyses and real cases of positioning development are rare. The objective of this paper is to analyse the existing theoretical fundamentals of positioning as well as day-to- day business practices and following that to formulate a positioning development model, a tool that will help marketers in brand management to create proper brand positioning and develop intended consumer brand perception. Keywords: positioning, consumer perception, brand differentiation Introduction The objective of branding is development of deep and long-lasting relationship with the consumer. Rational products´ or services´ attributes are no longer the decision drivers of the consumers´ choice as there is little differentiation of those among producers. Associated emotions are the decision makers. The issue is not just to produce what meets consumers´ expectations in terms of the rational product attributes but to successfully attract consumer interest.