Sexism in Advertising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Promotional Activities in Order to Win More Customers

Promotional Activities in Order to Win More Customers A case-study of an ISP in Bangladesh Master Degree Project in Business Administration One year. Advance Level, 15 ECTS Spring Term, 2011 Md. Razaul Karim Zhao Xu Supervisor: Peter Hultén,Ph.D Examiner: Stefan Tengblad Acknowledgement We would like to extent our sincerest thanks to all those who helped us to complete this research paper. We would like to extend our thanks and regards to our supervisor Mr. Peter Hultén, Ph.D who gave us distance supervision. We could not complete this research paper without his endless support. We would like to thanks all customers who expend their valuable time to fill up survey form and we also want to thanks Mr. Mashhurul Amin Nobin, Marketing Manager of Link3 Technologies Ltd. to give us time an opportunity to work with his renowned ICT Company. Above all, we would like to thanks Almighty Lord to give us knowledge and keep us healthy during the whole period of our research work. Md. Razaul Karim & Zhao Xu University of Skovde,June 2011 Table of Contents CHAPTER – 1: INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………………………………………………01-07 1.1 Background……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………01 1.2 Problem Discussion………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 03 1.3 Research Question…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………04 1.4 Research Purpose…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..04 1.5 Importance of This Research Paper………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..04 1.6 Limitation……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….05 -

A Do-It-Yourself Producer's Guide to Conducting Local Market Research

Agricultural Marketing Resource Center Value-added Agriculture Profile Iowa State University November 2008 A Do-It-Yourself Producer’s Guide to Conducting Local Market Research By Tommie L. Shepherd Agribusiness Economist Center for Agribusiness & Economic Development The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia Sharon P. Kane Food Business Development Specialist Center for Agribusiness & Economic Development The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia Audrey Luke-Morgan Agribusiness Economist Center for Agribusiness & Economic Development The University of Georgia, Tifton, Georgia Marcia W. Jones Agribusiness Economist Center for Agribusiness & Economic Development The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia John C. McKissick Director Center for Agribusiness & Economic Development The University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia Funding was provided by the Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. A Producer’s Guide to Conducting Local Market Research Introduction Many producers of agricultural commodities investigate the potential for develop- ing value-added products each year as a means of enhancing income from their farm- Introduction ing operations, capturing niche markets for locally grown food products or develop- ing new markets for products that spring from their own innovative ideas. These producers often lack both the technical skills necessary to conduct meaningful mar- ket research and the resources to hire professional consultants. University Extension programs frequently offer some level of assistance in these areas but often lack the time and industry specific knowledge to guide producers through in-depth studies tailored to individual products or markets. Value-added outreach and educational pro- grams are typically designed to present gen- eral information to groups of producers with diverse product interests, and as such, only discuss market research in very general terms, and then only as part of a broader curriculum. -

Sales Promotion in Conjoint Analysis

SALES PROMOTION IN CONJOINT ANALYSIS Eline van der Gaast, SKIM Marco Hoogerbrugge, SKIM RotterdamRotterdam | Geneva | Geneva | London | London | New | New York York 1 / 13 www.skiwww.skimgroup.mgroup.comcom SUMMARY This paper is about sales promotion as an attribute in conjoint studies. Promotions may involve a direct financial gain, and/or indirect benefits. A promotion generates extra attention for the product and the feeling of saving money. Typically, if one does a promotion that has the same financial savings to respondents as lowering the normal price, the effect of the promotion is much higher than simply reducing the price, due to the ‘attention’ effect. It is important to be aware that promotions provide a short-term benefit followed by a post-promotion dip. Even though promotions are difficult to study, conjoint analysis is effective in helping understand which promotion is more effective and which consumers you will attract with the promotion. Future research should aim to incorporate time elements into conjoint studies, to simulate more accurately purchase cycles and long-term effects of promotions. INTRODUCTION In times of economic crisis market research is a field that is actually blooming (Andrews, 2008). Especially during times of crisis companies have to make deliberate decisions on how to invest their marketing budget to optimize profits. In the fast moving consumer goods industry, competition is high and promotions are often used as a tool to increase sales. A promotional scheme that will provide the most optimal outcome will give a manufacturer a competitive advantage. Next to boosting short-term sales there are several other motives for using promotions in the consumer goods industry; eliciting trial among non-users or for new product introductions; dealing in markets with increased price sensitivity; and as an alternative for advertising. -

Positioning Guide

Positioning: How Advertising Shapes Perception © 2004 Learning Seed Voice 800.634.4941 Fax 800.998.0854 E-mail [email protected] www.learningseed.com Summary Positioning: How Advertising Shapes Perception uses ideas from advertising, psychology, and mass communication to explore methods marketers use to shape consumer perception. Traditional persuasion methods are less effective in a society besieged by thousands of advertising messages daily. Advertising today often does not attempt to change minds, it seldom demonstrates why one brand is superior, nor does it construct logical arguments to motivate a purchase. Increasingly, advertising is more about positioning than persuasion. The traditional approach to teaching “the power of advertising” is to borrow ideas from propaganda such as the bandwagon technique, testimonials, and glittering generalities. Although these ideas still work, they ignore the drastic changes in advertising in the past ten years. Advertisers recognize that “changing minds” is both very difficult and not really necessary. To position a product to fit the consumer’s existing mind set is easier than changing a mind. Consumers today see advertising more as entertainment or even “art” than as persuasion. Positioning means nothing less than controlling how people see. The word “position” refers to a place the product occupies in the consumer’s mind. Positioning attempts to shape perception instead of directly changing minds. Positioning works because it overcomes our resistance to advertising. The harder an ad tries to force its way into the prospect’s mind, the more defensive the consumers become. Nobody likes to be told how to think. As a result, advertising is used to position instead of to persuade. -

Aligning Sales Promotion Strategies with Buying Attitudes in a Recession Paulin Adjagbodjou Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2015 Aligning Sales Promotion Strategies With Buying Attitudes in a Recession Paulin Adjagbodjou Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Management and Technology This is to certify that the doctoral study by Paulin Adjagbodjou has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Janet Booker, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Peter Anthony, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Dr. Maurice Dawson, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2015 Abstract Aligning Sales Promotion Strategies With Buying Attitudes in a Recession by Paulin Adjagbodjou MS, Abomey-Calavi University, 2004 MBA, Abomey-Calavi University, 2002 BS, Abomey-Calavi University, 1995 Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Business Administration Walden University April 2015 Abstract Some managers lack an effective strategy for aligning sales promotion strategies with consumers’ buying attitudes in a recession. The intent of this comparative design was to determine the most effective sales promotion strategy for sales improvement and business sustainability during a recession. -

Product Positioning Strategy in Marketing Management

Journal of Naval Science and Engineering 2009, Vol. 5 , No 2, pp. 98-110 PRODUCT POSITIONING STRATEGY IN MARKETING MANAGEMENT Ph.D. Mustafa KARADENIZ, Nav. Cdr. Turkish Naval Academy Director of Naval Science and Engineering Institute Tuzla, Istanbul, Turkiye [email protected] Abstract In today’s globalizing and continuously developing economies, the competition among enterprises grows quickly, the market share gets narrower; and in order to gain new markets, companies are trying to create superiority over their rivals by positioning new products aimed at consumer behaviors and perceptions. In this sense, product positioning strategy in marketing management has emerged and now companies conduct studies on this strategy. In this research, product positioning strategy is emphasized and related examples are given. PAZARLAMA YÖNETİMİNDE ÜRÜN KONUMLADIRMA STRATEJİSİ Özetçe Küreselleşen ve sürekli gelişen günümüz ekonomilerinde işletmeler arasında rekabet hızla artmakta Pazar payı daralmakta ve şirketler yeni pazarlar elde etmek için tüketici davranış ve algılamalarına yönelik yeni ürünler konumlandırarak rakiplerine üstünlük ve farkındalık yaratmaya çalışmaktadırlar. Bu kapsamda, pazarlama yönetiminde ürün konumlandırma stratejisi ortaya çıkmış olup halen şirketler bu strateji üzerine çalışmalar yapmaktadırlar. Bu araştırmada ürün konumlandırma stratejisi üzerinde durulmuş ve konuya ilişkin örnekler verilmiştir. Keywords : Marketing, Product Positioning, Brand Anahtar Kelimeler : Pazarlama, Ürün Konumlandırma, Marka 98 Mustafa KARADENIZ -

A Comparative Study of Product Placement in Movies in the United States and Thailand

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 2007 A comparative study of product placement in movies in the United States and Thailand Woraphat Banchuen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the International Business Commons, and the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Banchuen, Woraphat, "A comparative study of product placement in movies in the United States and Thailand" (2007). Theses Digitization Project. 3265. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/3265 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PRODUCT PLACEMENT IN MOVIES IN THE UNITED STATES AND THAILAND A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Business Administration by Woraphat Banchuen June 2007 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF PRODUCT PLACEMENT IN MOVIES IN THE UNITED STATES AND THAILAND A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Woraphat Banchuen June 2007 Victoria Seitz, Committee Chair, Marketing ( Dr. Nabil Razzouk © 2007 Woraphat Banchuen ABSTRACT Product placement in movies is currently very popular in U.S. and Thai movies. Many companies attempted to negotiate with filmmakers so as to allow their products to be placed in their movies. Hence, the purpose of this study was to gain more understanding of how the products were placed in movies in the United States and Thailand. -

Product Placement Effects on Store Sales

Product Placement Effects on Store Sales: Evidence from Consumer Packaged Goods∗ Simha Mummalaneni † Yantao Wang ‡ Pradeep K. Chintagunta § Sanjay K. Dhar ¶ February 21, 2019 Abstract Product placement provides an alternative way for brands to reach consumers and does so in a more subtle way than through traditional advertising. We use data from both traditional television advertising and product placement on television shows to compare how these marketing instruments affect consumer demand for brands in the soda, diet soda, and coffee categories. Our approach is to estimate a logit demand model using weekly store-level sales data at the UPC (product) level, while accounting for heterogeneity in consumer preferences and response parameters across markets. Estimates from this model indicate that product placement is generally effective, but that the elasticities are small. For the soda and diet soda categories, average short-term elasticities are around 0.08 for the major brands in the data; these estimated elasticities for product placement are generally larger than those for traditional TV advertising, albeit on the same order of magnitude. For the coffee category, product placement elasticities are roughly zero while the advertising elasticities are larger. The results suggest that product placement is overall more effective than traditional TV advertising for the brands in our data; however, there is a significant amount of heterogeneity in elasticities across categories, brands, and geographical areas. Keywords: Product Placement, Advertising, Media, Demand Estimation ∗We thank Günter Hitsch for initiating this project with us. We also thank Brad Shapiro and seminar participants at the 2018 UW-UBC marketing camp, the 2018 Marketing Science conference, Johns Hopkins University, the FTC Bureau of Economics, and the 2019 University of Washington winter marketing camp for their thoughtful comments and suggestions. -

Sex Sells: How Advertising Agencies' Commodification of Image Affects Older Women in Advertising Diane Fittipaldi University of St

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education Spring 2015 Sex Sells: How Advertising Agencies' Commodification of Image Affects Older Women in Advertising Diane Fittipaldi University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Business and Corporate Communications Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Education Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Interpersonal and Small Group Communication Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, Organizational Communication Commons, and the Public Relations and Advertising Commons Recommended Citation Fittipaldi, Diane, "Sex Sells: How Advertising Agencies' Commodification of Image Affects Older Women in Advertising" (2015). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 56. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/56 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEX SELLS i Sex Sells: How Advertising Agencies’ Commodification of Image Affects Older Women in Advertising A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF EDUCTATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA By Diane Fittipaldi IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION 2014 SEX SELLS ii UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS, MINNESOTA Sex Sells: How Advertising Agencies’ Commodification of Image Affects Older Women in Advertising We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as meeting departmental criteria for graduating with honors in scope and quality. -

5 Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

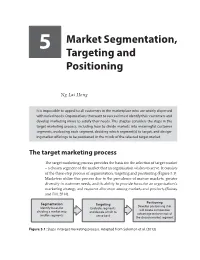

Market Segmentation, 5 Targeting and Positioning Ng Lai Hong It is impossible to appeal to all customers in the marketplace who are widely dispersed with varied needs. Organisations that want to succeed must identify their customers and develop marketing mixes to satisfy their needs. This chapter considers the steps in the target marketing process, including how to divide markets into meaningful customer segments, evaluating each segment, deciding which segment(s) to target, and design- ing market offerings to be positioned in the minds of the selected target market. The target marketing process The target marketing process provides the basis for the selection of target market – a chosen segment of the market that an organisation wishes to serve. It consists 84 Fundamentalsof the three-step of Marketing process of segmentation, targeting and positioning (Figure 5.1). Marketers utilise this process due to the prevalence of mature markets, greater diversity in customer needs, and its ability to provide focus for an organisation’s marketing strategy and resource allocation among markets and products (Baines and Fill, 2014). Segmentation Positioning Targeting Develop positioning that Identify bases for Evaluate segments will create competitive dividing a market into and decide which to advantage in the minds of smaller segments serve best the chosen market segment Figure 5.1: Steps in target marketing process. Adapted from Solomon et al. (2013). 86 Fundamentals of Marketing The benefits of this process include the following: Understanding customers’ needs. The target marketing process provides a basis for understanding customers’ needs by grouping customers with similar characteristics together and for the selection of target market. -

The Effects of Product Placement, in Films, on the Consumers' Purchase

THE EFFECTS OF PRODUCT PLACEMENT, IN FILMS, ON THE CONSUMERS’ PURCHASE INTENTIONS Nuno Alexandre Gaspar da Silva Oliveira Barroso Dissertation submitted as partial requirement for MSc. in Marketing Supervisor: PhD. Paulo Rita, ISCTE Business School, Department of Management Co-Supervisor: PhD. Francisco Esteves, ISCTE-IUL, Department of Psychology December 2011 The Effects of Product Placement, in Films, on the Consumers’ Purchase Intentions ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are some people that deserve a mention because they were of extreme importance in order to conclude this paper. In first place, I would like to acknowledge my supervisor PhD. Paulo Rita for all his support over the last year. In instances where I would feel a little bit lost, his insights, opinions and comments weighted gold. For that, I am extremely thankful. I would also like to acknowledge my co-supervisor, PhD. Francisco Esteves, for providing me the conditions to perform the laboratory experience, for his different insights and views to the research, that have given me a broader look into the product placement theme. To my Father and Mother for all the love, care, support and respect they have been giving me throughout all these years. For encouraging me always to give my best, no matter how difficult the situations may appear to be. Thank you. To my brothers, for being constant sources of laughter in my life and for the constant interest they took in my thesis. To everyone in my team, the Voice Product Direction at ZON Multimédia, for being understanding and flexible, giving me the margin I needed to concluded this paper. -

Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning

Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning By Mark Anthony Camilleri 1, PhD (Edinburgh) How to Cite : Camilleri, M. A. (2018). Market Segmentation, Targeting and Positioning. In Travel Marketing, Tourism Economics and the Airline Product (Chapter 4, pp. 69-83). Springer, Cham, Switzerland. Abstract Businesses may not be in a position to satisfy all of their customers, every time. It may prove difficult to meet the exact requirements of each individual customer. People do not have identical preferences, so rarely does one product completely satisfy everyone. Therefore, many companies may usually adopt a strategy that is known as target marketing. This strategy involves dividing the market into segments and developing products or services to these segments. A target marketing strategy is focused on the customers’ needs and wants. Hence, a prerequisite for the development of this customer-centric strategy is the specification of the target markets that the companies will attempt to serve. The marketing managers who may consider using target marketing will usually break the market down into groups (segments). Then they target the most profitable ones. They may adapt their marketing mix elements, including; products, prices, channels, and promotional tactics to suit the requirements of individual groups of consumers. In sum, this chapter explains the three stages of target marketing, including; market segmentation (ii) market targeting and (iii) market positioning. 4.1 Introduction Target marketing involves the identification of the most profitable market segments. Therefore, businesses may decide to focus on just one or a few of these segments. They may develop products or services to satisfy each selected segment.