Ministerial Responsibility for Administrative Actions: Some Observations of a Public Service Practitioner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index to Votes and Proceedings

THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA 30TH PARLIAMENT--IST SESSION-1976-77 Index to Votes and Proceedings FOR PROCEEDINGS ON BILLS, SEE UNDER "BILLS" FOR MESSAGES FROM GOVERNOR-GENERAL AND FROM SENATE, SEE UNDER MESSAGES (p. xxxvi); AND ALSO SEE APPENDICES I AND 2 (pp. 623-4) FOR PAPERS LAID UPON THE TABLE, SEE "INDEX TO PAPERS PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT" (p. lxi) A Aboriginal- Affairs, Council for. See "Ministerial statements" and "Statements". Affairs. See "Committees", "Ministerial statements", "Petitions" and "Statements". Health. See "Public importance-Discussion of matters of'. Land Rights (Northern Territory) Bills. See "Petitions" and "Statements". Land Rights in the Northen Territory. See "Committees". People-Government's policies. See "Public importance-Discussion of matters of"'. Studies, Australian Institute of-Appointment of Members to Council, 52. Absence of Ministers. See "Ministry". Absolute majority. See "Standing orders-Suspension of'. Acting Clerk of the House-Announces absence of Mr Speaker, 303. Acting Speaker (Mr Lucock)-- Presents paper, 326. Takes Chair during absence of Mr Speaker, 303. Welcomes distinguished visitors, 310. And see "Rulings". Address- By Deputy of Governor-General-Declaration of Opening of Parliament, 2. To His Excellency the Governor-General (Sir John Kerr)- In reply to Opening Speech- Committee appointed to prepare Address, 9. Discharge of Member; appointment of another Member, 21. Address brought up, 22. Motion-That Address be agreed to-debated, 22, 26, 30, 37, 41. Amendment moved (Dr Jenkins), 41-2. Motion and amendment debated, 42, 44, 54, 55, 69-70,86,95, 102-3. Amendment negatived; Address agreed to, 103. Presentation, and Reply-Announced, 125-6. -

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-Funded Flights Taken by Former Mps and Their Widows Between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed in Descending Order by Number of Flights Taken

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-funded flights taken by former MPs and their widows between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed in descending order by number of flights taken NAME PARTY No OF COST $ FREQUENT FLYER $ SAVED LAST YEAR IN No OF YEARS IN FLIGHTS FLIGHTS PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT Ian Sinclair Nat, NSW 701 $214,545.36* 1998 25 Margaret Reynolds ALP, Qld 427 $142,863.08 2 $1,137.22 1999 17 Gordon Bilney ALP, SA 362 $155,910.85 1996 13 Barry Jones ALP, Vic 361 $148,430.11 1998 21 Graeme Campbell ALP/Ind, WA 350 $132,387.40 1998 19 Noel Hicks Nat, NSW 336 $99,668.10 1998 19 Dr Michael Wooldridge Lib, Vic 326 $144,661.03 2001 15 Fr Michael Tate ALP, Tas 309 $100,084.02 11 $6,211.37 1993 15 Frederick M Chaney Lib, WA 303 $195,450.75 19 $16,343.46 1993 20 Tim Fischer Nat, NSW 289 $99,791.53 3 $1,485.57 2001 17 John Dawkins ALP, WA 271 $142,051.64 1994 20 Wallace Fife Lib, NSW 269 $72,215.48 1993 18 Michael Townley Lib/Ind, Tas 264 $91,397.09 1987 17 John Moore Lib, Qld 253 $131,099.83 2001 26 Al Grassby ALP, NSW 243 $53,438.41 1974 5 Alan Griffiths ALP, Vic 243 $127,487.54 1996 13 Peter Rae Lib, Tas 240 $70,909.11 1986 18 Daniel Thomas McVeigh Nat, Qld 221 $96,165.02 1988 16 Neil Brown Lib, Vic 214 $99,159.59 1991 17 Jocelyn Newman Lib, Tas 214 $67,255.15 2002 16 Chris Schacht ALP, SA 214 $91,199.03 2002 15 Neal Blewett ALP, SA 213 $92,770.32 1994 17 Sue West ALP, NSW 213 $52,870.18 2002 16 Bruce Lloyd Nat, Vic 207 $82,158.02 7 $2,320.21 1996 25 Doug Anthony Nat, NSW 204 $62,020.38 1984 27 Maxwell Burr Lib, Tas 202 $55,751.17 1993 18 Peter Drummond -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1974 AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE TWENTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 9 JULY 1974 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the ninth day of July, in the twenty-third year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and seventy-four. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Norman James Parkes, O.B.E., Clerk of the House of Representatives, John Athol Pettifer, Deputy Clerk, and Grahame John Horsfield, Acting Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION Australia By His Excellency the PAUL HASLUCK Governor-General of Australia Governor-General WHEREAS by the Constitution it is, amongst other things, provided that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now THEREFORE I, Sir Paul Meernaa Caedwalla Hasluck, the Governor-General of Australia, do by this my Proclamation appoint Tuesday, 9 July 1974, as the day for the Parliament to assemble for the despatch of business: And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly at Parliament House, Canberra, at 10.30 o'clock in the morning, on Tuesday, 9 July 1974. Given under my Hand on June 25th 1974. -

Ministers for Foreign Affairs 1972-83

Ministers for Foreign Affairs 1972-83 Edited by Melissa Conley Tyler and John Robbins © The Australian Institute of International Affairs 2018 ISBN: 978-0-909992-04-0 This publication may be distributed on the condition that it is attributed to the Australian Institute of International Affairs. Any views or opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily shared by the Australian Institute of International Affairs or any of its members or affiliates. Cover Image: © Tony Feder/Fairfax Syndication Australian Institute of International Affairs 32 Thesiger Court, Deakin ACT 2600, Australia Phone: 02 6282 2133 Facsimile: 02 6285 2334 Website:www.internationalaffairs.org.au Email:[email protected] Table of Contents Foreword Allan Gyngell AO FAIIA ......................................................... 1 Editors’ Note Melissa Conley Tyler and John Robbins CSC ........................ 3 Opening Remarks Zara Kimpton OAM ................................................................ 5 Australian Foreign Policy 1972-83: An Overview The Whitlam Government 1972-75: Gough Whitlam and Don Willesee ................................................................................ 11 Professor Peter Edwards AM FAIIA The Fraser Government 1975-1983: Andrew Peacock and Tony Street ............................................................................ 25 Dr David Lee Discussion ............................................................................. 49 Moderated by Emeritus Professor Peter Boyce AO Australia’s Relations -

Votes and Proceedings

1969 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE TWENTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 25 NOVEMBER 1969 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the twenty-fifth day of November, in the eighteenth year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and sixty-nine. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), Alan George Turner, C.B.E., Clerk of the House of Representatives, Norman James Parkes, O.B.E., Deputy Clerk, John Athol Pettifer, Clerk Assistant, and Lyndal McAlpin Barlin, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION Commonwealth of By His Excellency the Governor-General in and over the Australia to wit Commonwealth of Australia. PAUL HASLUCK Governor-General. WHEREAS by the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is amongst other things provided that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holding the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now therefore I, Sir Paul Meernaa Caedwalla Hasluck, the Governor-General aforesaid, in the exercise of the power conferred by the Constitution, do by this my Proclama- tion appoint Tuesday, the twenty-fifth day of November, One thousand nine hundred and sixty-nine, as the day for the Parliament to assemble and be holden for the despatch of divers urgent and important affairs: and all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly in the building known as Parliament House, Canberra, at the hour of eleven o'clock in the morning on the twenty-fifth day of November, One thousand nine hundred and sixty-nine. -

A Handbook of Australian Government and Politics 1965-1974 This Book Was Published by ANU Press Between 1965–1991

A Handbook of Australian Government and Politics 1965-1974 This book was published by ANU Press between 1965–1991. This republication is part of the digitisation project being carried out by Scholarly Information Services/Library and ANU Press. This project aims to make past scholarly works published by The Australian National University available to a global audience under its open-access policy. COLIN A. HUGHES A Handbook of Australian Government and Politics 1965-1974 AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY PRESS CANBERRA 1977 First published in Australia 1977 Printed in Australia for the Australian National University Press, Canberra, at Griffin Press Limited, Netley, South Australia © Colin A. Hughes 1977 This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Hughes, Colin Anfield. A handbook of Australian government and politics, 1965-1974. ISBN 0 7081 1340 0. 1. Australia—Politics and government—Handbooks, manuals, etc. I. Title. 320.994 Southeast Asia: Angus & Robertson (S.E. Asia) Pty Ltd, Singapore Japan: United Publishers Services Ltd, Tokyo Acknowledgments This Handbook closely follows the model of its predecessor, A Handbook o f Australian Government and Politics 1890-1964, of which Professor Bruce Graham was co-editor, and my first debt is to him for the collaboration which laid down the ground rules. Mrs Geraldine Foley, who had been the principal research assistant for the original work, very kindly fitted in work on electoral data with her family responsibilities; once more her support has been invaluable. -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

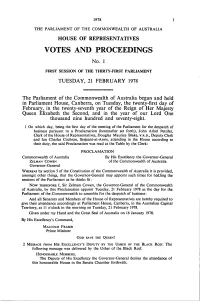

1978 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 1 FIRST SESSION OF THE THIRTY-FIRST PARLIAMENT TUESDAY, 21 FEBRUARY 1978 The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia begun and held in Parliament House, Canberra, on Tuesday, the twenty-first day of February, in the twenty-seventh year of the Reign of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Second, and in the year of our Lord One thousand nine hundred and seventy-eight. 1 On which day, being the first day of the meeting of the Parliament for the despatch of business pursuant to a Proclamation (hereinafter set forth), John Athol Pettifer, Clerk of the House of Representatives, Douglas Maurice Blake, V.R.D., Deputy Clerk and Ian Charles Cochran, Serjeant-at-Arms, attending in the House according to their duty, the said Proclamation was read at the Table by the Clerk: PROCLAMATION Commonwealth of Australia By His Excellency the Governor-General ZELMAN COWEN of the Commonwealth of Australia Governor-General WHEREAS by section 5 of the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia it is provided, amongst other things, that the Governor-General may appoint such times for holIing the sessions of the Parliament as he thinks fit: Now THEREFORE I, Sir Zelman Cowen, the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia, by this Proclamation appoint Tuesday, 21 February 1978 as the day for the Parliament of the Commonwealth to assemble for the despatch of business: And all Senators and Members of the House of Representatives are hereby required to give their attendance accordingly at Parliament House, Canberra, in the Australian Capital Territory, at 11 o'clock in the morning on Tuesday, 21 February 1978. -

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-Funded Flights Taken by Former Mps and Their Widows Between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed by Total Cost of All Flights Taken

The Gravy Plane Taxpayer-funded flights taken by former MPs and their widows between January 2001 and June 2008 Listed by total cost of all flights taken NAME PARTY No OF COST $ FREQUENT FLYER $ SAVED LAST YEAR IN No OF YEARS IN FLIGHTS FLIGHTS PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT Ian Sinclair Nat, NSW 701 $214,545.36* 1998 25 Frederick M Chaney Lib, WA 303 $195,450.75 19 $16,343.46 1993 20 Gordon Bilney ALP, SA 362 $155,910.85 1996 13 Barry Jones ALP, Vic 361 $148,430.11 1998 21 Dr Michael Wooldridge Lib, Vic 326 $144,661.03 2001 15 Margaret Reynolds ALP, Qld 427 $142,863.08 2 $1,137.22 1999 17 John Dawkins ALP, WA 271 $142,051.64 1994 20 Graeme Campbell ALP/Ind, WA 350 $132,387.40 1998 19 John Moore Lib, Qld 253 $131,099.83 2001 26 Alan Griffiths ALP, Vic 243 $127,487.54 1996 13 Fr Michael Tate ALP, Tas 309 $100,084.02 11 $6,211.37 1993 15 Tim Fischer Nat, NSW 289 $99,791.53 3 $1,485.57 2001 17 Noel Hicks Nat, NSW 336 $99,668.10 1998 19 Neil Brown Lib, Vic 214 $99,159.59 1991 17 Janice Crosio ALP, NSW 154 $98,488.80 2004 15 Daniel Thomas McVeigh Nat, Qld 221 $96,165.02 1988 16 Martyn Evans ALP, SA 152 $92,770.46 2004 11 Neal Blewett ALP, SA 213 $92,770.32 1994 17 Michael Townley Lib/Ind, Tas 264 $91,397.09 1987 17 Chris Schacht ALP, SA 214 $91,199.03 2002 15 Peter Drummond Lib, WA 198 $87,367.77 1987 16 Ian Wilson Lib, SA 188 $82,246.06 6 $1,889.62 1993 24 Percival Clarence Millar Nat, Qld 158 $82,176.83 1990 16 Bruce Lloyd Nat, Vic 207 $82,158.02 7 $2,320.21 1996 25 Prof Brian Howe ALP, Vic 180 $80,996.25 1996 19 Nick Bolkus ALP, SA 147 $77,803.41 -

Notes on Sources and References………………………………………………….……..Ii

THE DE-COLONISATION OF THE AUSTRALIAN STATES by ANNE TWOMEY A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES APRIL 2006 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the status of the Queen in Australia in relation to the Australian States and the effect upon it of the enactment of the Australia Acts 1986. It uses hitherto confidential government documents to expose the true relationship between the United Kingdom, the Crown and the States and challenge prevailing assumptions. The thesis establishes that before 1986 the United Kingdom played a substantive, rather than a merely formal, role in the constitutional relationship between the States and the Crown. The ‘Queen of Australia’ was confined in her role to Commonwealth, not State, matters. The ‘Queen of the United Kingdom’ continued to perform constitutional functions with respect to the States, which were regarded as dependencies of the British Crown. This position changed with the enactment of the Australia Acts 1986 (Cth) and (UK). This thesis analyses the Australia Acts, assesses the validity of their provisions and contends that the Australia Act 1986 (UK) was necessary for legal and political reasons. The thesis concludes that the Australia Acts, in terminating the residual sovereignty of the Westminster Parliament with respect to Australia, transferred sovereignty collectively to the components of the federal parliamentary democratic system. Consistent with this view, it is contended that the effect of the Australia Acts was to establish a hybrid federal Crown of Australia under which the Queen’s Ministers for each constituent polity within the federation can advise her upon her constitutional functions with respect to that polity. -

VOTES and PROCEEDINGS No

1980-81 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 11 WEDNESDAY, 4 MARCH 1981 1 The House met, at 2.15 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Right Honour- able Sir Billy Snedden) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 RETURNS TO WRITS-CURTIN AND MCPHERSON DIVISIONS: Mr Speaker announced that he had received returns to the writs which he had issued on 27 January 1981 for the election of Members to serve for the Electoral Divisions of Curtin, in the State of Western Australia, and McPherson, in the State of Queensland, to fill the vacancies caused by the resignation of the Honourable Ransley Victor Garland and the death of the Honourable Eric Laidlaw Robinson, respectively. By the endorsement on the writs, it was certified that Allan Charles Rocher had been elected as the Member to serve for the Division of Curtin and that Peter Nicholson Duckett White had been elected as the Member to serve for the Division of McPherson. 3 OATHS OF ALLEGIANCE BY MEMBERS: Allan Charles Rocher and Peter Nicholson Duckett White were introduced, and made and subscribed the oath of allegiance required by law. 4 DEATH OF SENATOR J. W. KNIGHT: Mr Fraser (Prime Minister) referred to the death of Senator J. W. Knight, and moved-That the House expresses its deep regret at the death this day of Senator John William Knight, a Senator for the Australian Capital Territory from 1975 and Government Whip in the Senate from 1980, places on record its appreciation of his long and meritorious public service, and tenders its profound sympathy to his widow and the members of his family in their bereavement.