Reputation: Content, Structure, and Trajectories Hooria Jazaieri a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implicitly Defined Baseball Statistics

Implicitly Defined Baseball Statistics December 9, 2012 Joe Scott 1 Introduction Major League Baseball uses statistics to determine awards every season. The batting champion is given to the player with the highest batting average. The Cy Young Award is given to the top pitcher which is determined by many different statistics including earned run average (ERA). Batting average and ERA have been used for many years and are major statistics in baseball. Neither batting average or ERA consider the skill of the opposing pitcher or batter. Thus, every pitcher and batter is considered to have the same skill level. We develop an implicitly definded statistic that determines the skill or value of a player. The value of a batter and the value of a pitcher is based on the skill of the oppposing pitcher and batter respectively. We use linear algebra to find eigenvector solutions to the eigenvalue problem, Aλ = λx, which generates each player's statistical value. 2 Idea Consider a baseball league in which there are Nb players who bat, represented by bi for 1 ≤ i ≤ Nb. We represent the number of pitchers in the league as pj, 1 ≤ j ≤ Np where Np is the number of pitchers. Nb is defined as the number players who record an at bat during a specific season and Np is the number of players who record a pitching appearance during a season. The total number of players in the league, Ntp, is represented by the inequality Ntb ≤ Nb + Np. This inequality considers players who both hit and pitch. Since in the National League pitchers hit as well as pitch we need to add the pitchers to the total number of batters and in interleague play (which is when American League teams face National League teams in the regular season) American League pitchers bat when the National League team is home. -

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings November 21, 2012

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings November 21, 2012 CINCINNATI ENQUIRER Pitching is pricey, transactions By John Fay | 11/20/2012 12:17 PM ET Want to know why the Reds would be wise to lock up Homer Bailey and Mat Latos long-term? The Kansas City Royals agreed to a three-year deal with Jeremy Guthrie that pays him $5 million on 2013, $11 million in 2014 and $9 million in 2015. He went 8-12 with a 4.76 ERA and 1.41 WHIP. Bailey went 13-10 with a 3.68 ERA and a 1.24 WHIP. Latos went 14-4 with a 2.48 ERA and a 1.16 WHIP. It’s a bit apples and oranges: Guthrie is a free agent; Bailey is arbitration-eligible for the second time, Latos for the first. But the point is starting pitching — even mediocre starting pitching — is expensive. SIX ADDED: The Reds added right-handers Carlos Contreras, Daniel Corcino, Curtis Partch and Josh Ravin, left-hander Ismael Guillon and outfielder Yorman Rodriguez to the roster in order to protect them from the Rule 5 draft. Report: Former Red Frank Pastore badly hurt in motorcycle wreck By dclark | 11/20/2012 7:55 PM ET The Inland Valley Daily Bulletin is reporting that former Cincinnati Reds pitcher Frank Pastore, a Christian radio personality in California, was badly injured Monday night after being thrown from his motorcycle onto the highway near Duarte, Calif. From dailybulletin.com’s Juliette Funes: A 55-year-old motorcyclist from Upland was taken to a trauma center when his motorcycle was hit by a car on the 210 Freeway Monday night. -

04-30-2015 Angels Game Notes

ANGELS (10-11) @ ATHLETICS (9-13) RHP GARRETT RICHARDS (1-1, 3.75 ERA) vs. RHP JESSE CHAVEZ (0-1, 0.71 ERA) O.Co COLISEUM – 12:37 PM PDT TV – FOX SPORTS WEST RADIO – KLAA AM 830 THURSDAY, APRIL 30, 2015 GAME #22 (10-11) OAKLAND, CA ROAD GAME #12 (6-5) LEADING OFF: Today the Angels play the ‘rubber match’ GAME OF CRON: On Sunday, C.J. Cron’s four hits set a at Oakland and the third game (1-1) of a six-game Bay single-game career-high…He has recorded nine hits in his THIS DATE IN ANGELS HISTORY Area road trip to Oakland (April 28-30; 1-1) and San last 18 at-bats and has three doubles his last seven games. April 30 (2008) A day after Joe Saunders Francisco (May 1-3)…Halos are in a stretch of 25 moves to 5-0, Ervin Santana consecutive days in California (April 20-May 14)…LAA ABOUT FACE: Thru 21 games in 2014, David Freese tallied becomes the third pitcher in club went 4-3 on the seven-game home stand vs. Oakland (2- 13 hits, one double, one home run and six RBI…Thru 21 history to go 5-0 in April…The duo 2) and Texas (2-1)…Following this trip, Angels will host a games in 2015, owns 17 hits, four doubles, four home runs becomes just the second tandem nine-game home stand vs. Seattle (May 4-6), Houston and a team-leading 15 RBI. in MLB history to boast two (May 7-10) and Colorado (May 12-13). -

Boston Red Sox (82-57) Vs

BOSTON RED SOX (82-57) VS. DETROIT TIGERS (81-57) Tuesday, September 3, 2013 • 7:10 p.m. ET • Fenway Park, Boston, MA LHP Jon Lester (12-8, 3.99) vs. RHP Max Scherzer (19-1, 2.90) Game #140 • Home Game #71 • TV: NESN/MLBN • Radio: WEEI 93.7 FM, WUFC 1510 AM (Spanish) STANDING TALL: Boston plays the 2nd of 3 games LESTER’S LAST 5: Tonight’s starter Jon Lester has quality against the Tigers tonight in the 3rd and fi nal series of a starts in his last 5 outings since 8/8...In that time, he ranks RED SOX RECORD BREAKDOWN Overall ........................................... 82-57 9-game homestand...The Sox are 5-2 thus far on the stand, 3rd in the AL in ERA (tied, 1.80) and opponent AVG (.198). AL East Standing ....................1st, 5.5 GA after taking 2 of 3 from Baltimore, sweeping the White Sox At Home ......................................... 45-25 in 3 games, and dropping last night’s series opener. PEN STRENGTH: The Red Sox bullpen has been charged On Road ......................................... 37-32 On the homestand, the Sox are outscoring opponents with runs in just 1 of 7 games during the current homes- In day games .................................. 25-13 37-22 with a .286 batting average and a 3.14 ERA. tand...In that time, Sox relievers have allowed just 2 runs In night games ............................... 57-44 and 8 hits over 18.2 innings (0.96 ERA). April ................................................. 18-8 Boston’s weekend sweep of the White Sox was the May ................................................ 15-15 club’s 1st sweep since 7/30-8/1 vs. -

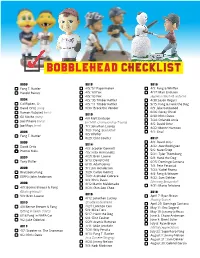

Bobblehead Checklist

BOBBLEHEAD CHECKLIST 2003: 2012: 2016: Fang T. Rattler 4/5: ‘52 Papermaker 4/9: Fang & Whiffer Harold Baines 4/5: ‘60 Fox 4/17: Matt Erickson 4/5: ‘83 Fox (Appleton West HS uniform) 2004: 4/5: ‘95 Timber Rattler 4/30: Jason Rogers Cal Ripken, Sr. 4/5: ‘11 Timber Rattler 5/15: Fang & Hank the Dog David Ortiz (mini) 8/30: Brock the Vendor 6/9: Jake Gatewood 6/26: Corey Chisel Ramon Vazquez (mini) 2013: 6/30: Khris Davis Gil Meche (mini) 4/8 Matt Erickson 7/24: Orlando Arcia Joel Pineiro (mini) (w/ MWL Championship Trophy) 8/5: David Ortiz Joe Mays (mini) 7/1: Jonathan Lucroy 8/22: Monte Harrison 7/26: Fang (Bobbletail) 2005: 9/1: Gnaf 8/5 Whiffer Fang T. Rattler 8/29: Clint Coulter 2017: 2006: 4/8: David Ortiz 2014: David Ortiz 4/22: Alex Rodriguez 4/3: Scooter Gennett 5/6: Nate Griep Promo Nikki 4/5: Felix Hernandez 5/21: Tyler Thornburg 4/29: Brett Lawrie 2007: 6/8: Hank the Dog 5/13: David Ortiz Tony Butler 6/25: Domingo Santana 6/10: Adam Jones 7/8: Pete Petoniak 2008: 7/1: Jim Henderson 7/23: Yadiel Rivera 7/20: Carlos Gomez Bratzooka Fang 8/4: Fang & Weaver 7/29: Asdrubal Cabrera ESPN’s John Anderson 8/22: Sam Dekker 8/3: Khris Davis (Shooting Bratzooka!) 2009: 8/12 Martin Maldonado 8/31: Mario Feliciano 4/9: Bernie Brewer & Fang 8/28: Shin-Soo Choo (Shaking Hands) 2018: 2015: 9/3: Brett Lawrie April 7: Ryan Braun 4/12: Jonathan Lucroy (Batting Stance) 2010: (Double bobblehead) April 29: Domingo Santana 4/24: Lorenzo Cain 4/8 Bernie Brewer & Fang May 11: Eric Sogard 5/3: Mike Fiers (Sitting in beach chairs) May 19: Jeremy Jeffress 5/17: Hank the Dog 6/16 Fang in NAPA Car June 3: Chase Anderson 6/4: Clint Coulter 9/2: Jake Odorizzi June 8: Brent Suter 6/29: Aramis Ramirez July 8: Ryan Braun 2011: 7/16: Mike Jirschele (Military Appreciation) 7/26: Wily Peralta 4/7: Scooter vs. -

Oakland Athletics

Oakland Athletics Roster (as of July 23, 2015) Oakland Athletics Baseball Company 7000 Coliseum Way Oakland, CA 94621 510-638-4900 www.athletics.com A’s PR on Twitter @AsMediaAlerts NO PITCHERS (12) B T HT WT BORN BIRTHPLACE RESIDENCE NUMERICAL ROSTER 56 Fernando Abad L L 6-1 220 12-17-85 La Romana, D.R. La Romana, D.R. 1 Billy Burns, OF 30 Jesse Chavez R R 6-2 160 8-21-83 Victorville, CA Pomona, CA 5 Jake Smolinski, OF 36 Tyler Clippard R R 6-3 201 2-14-85 Lexington, KY Clearwater, FL 10 Marcus Semien, SS 31 Kendall Graveman R R 6-2 185 12-21-90 Alexander City, AL Alexander City, AL 13 Drew Pomeranz, LHP 54 Sonny Gray R R 5-11 180 11-7-89 Nashville, TN Smyrna, TN 68 Arnold Leon R R 6-1 206 9-6-88 Culiacan, Mexico Culiacan, Mexico 15 Brett Lawrie, 3B 49 Edward Mujica R R 6-3 220 5-10-84 Valencia, Venezuela Yagua, Venezuela 16 Billy Butler, DH 39 Eric O’Flaherty L L 6-2 220 2-5-85 Walla Walla, WA Walla Walla, WA 17 Ike Davis, 1B 61 Dan Otero R R 6-3 214 2-19-85 Miami, FL Scottsdale, AZ 18 Ben Zobrist, IF/OF 13 Drew Pomeranz R L 6-5 240 11-22-88 Collierville, TN Collierville, TN 19 Josh Phegley, C 33 Fernando Rodriguez R R 6-3 237 6-18-84 El Paso, TX El Paso, TX 20 Mark Canha, IF/OF 58 Evan Scribner R R 6-3 190 7-19-85 New Milford, CT Washington Depot, CT 21 Stephen Vogt, C NO CATCHERS (2) B T HT WT BORN BIRTHPLACE RESIDENCE 22 Josh Reddick, OF 19 Josh Phegley R R 5-10 225 2-12-88 Terre Haute, IN Indianapolis, IN 23 Sam Fuld, OF 21 Stephen Vogt L R 6-0 215 11-1-84 Visalia, CA Tumwater, WA NO INFIELDERS (7) B T HT WT BORN BIRTHPLACE -

F(Error) = Amusement

Academic Forum 33 (2015–16) March, Eleanor. “An Approach to Poetry: “Hombre pequeñito” by Alfonsina Storni”. Connections 3 (2009): 51-55. Moon, Chung-Hee. Trans. by Seong-Kon Kim and Alec Gordon. Woman on the Terrace. Buffalo, New York: White Pine Press, 2007. Peraza-Rugeley, Margarita. “The Art of Seen and Being Seen: the poems of Moon Chung- Hee”. Academic Forum 32 (2014-15): 36-43. Serrano Barquín, Carolina, et al. “Eros, Thánatos y Psique: una complicidad triática”. Ciencia ergo sum 17-3 (2010-2011): 327-332. Teitler, Nathalie. “Rethinking the Female Body: Alfonsina Storni and the Modernista Tradition”. Bulletin of Spanish Studies: Hispanic Studies and Researches on Spain, Portugal and Latin America 79, (2002): 172—192. Biographical Sketch Dr. Margarita Peraza-Rugeley is an Assistant Professor of Spanish in the Department of English, Foreign Languages and Philosophy at Henderson State University. Her scholarly interests center on colonial Latin-American literature from New Spain, specifically the 17th century. Using the case of the Spanish colonies, she explores the birth of national identities in hybrid cultures. Another scholarly interest is the genre of Latin American colonialist narratives by modern-day female authors who situate their plots in the colonial period. In 2013, she published Llámenme «el mexicano»: Los almanaques y otras obras de Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (Peter Lang,). She also has published short stories. During the summer of 2013, she spent time in Seoul’s National University and, in summer 2014, in Kyungpook National University, both in South Korea. https://www.facebook.com/StringPoet/ The Best Players in New York Mets History Fred Worth, Ph.D. -

Spring Notes

SPRING TRAINING GAME NOTES NEW YORK YANKEES (18-6) vs. BOSTON RED SOX (11-12-2) YANKEES ROSTER RHP Bryan Mitchell (2-1, 3.77) vs. LHP Chris Sale (1-0, 3.60) 11 Brett Gardner . OF 12 Chase Headley . .INF Probable relievers for NYY: LHP Aroldis Chapman, RHP Luis Cessa and LHP Jon Niese 14 Starlin Castro . .INF 17 Matt Holliday . .DH Tuesday, March 21, 2017 • GMS Field • Tampa, Florida • 6:35 p.m. ET 18 Didi Gregorius . .INF Game #26 • Home Game #13 • TV: None • Radio: None 19 Masahiro Tanaka . .RHP 22 Jacoby Ellsbury . OF 24 Gary Sánchez . C AT A GLANCE: The New York Yankees will play the 26th exhibition game of their spring schedule tonight vs. the Boston 26 Tyler Austin . .INF/OF Red Sox in Tampa, Fla.… will be the second of two spring training matchups between the two teams in 2017… will play 27 Austin Romine . C 35 total spring games, all but one against MLB opposition (10-4 win vs. Team Canada on 3/8)… are slated for 17 home 28 Joe Girardi . MANAGER games… will play six night games, including fi ve at home (left to play: 3/28 vs. Detroit) and one on the road (3/31 at Atlanta 29 Tyler Clippard^ . .RHP at SunTrust Park)… each of the Yankees’ home night games will start at 6:35 p.m.… marks the Yankees’ 22nd consecutive 30 Rubén Tejada* . .INF season at Steinbrenner Field (1996-2017), formerly Legends Field. 31 Aaron Hicks . OF The Yankees’ 18 spring wins match their highest total since 2010 (18-12-3 in 2012)…their highest win total over the 33 Greg Bird . -

2011 Auction Catalogue-Leftovers

Remaining Auction Items from the 2011 Baseball Canada National Teams Fundraiser *Auction ends February 1st, 2011 at 12am *To submit a bid please send e-mail to [email protected] As of January 31st, 2011 with your name,phone#, item # and bid amount ITEM TEAM OR Minimum Current ITEM SIGNATURE or DESCRIPTION # LOCATION Bid Bid HOCKEY STICK used in Pre 2009 Selected members of 2009 WBC TEAM CANADA A15 $100 WBC Ball Hockey Game - Taped handle Justin Morneau, Russell Martin, Scott Richmond and others RIO FERDINAND DESIGNED A17 Limited Edition $80 NEW ERA 5950 CAP Autographed Team Canada Jersey from 2010 FIBA World A22 Canada Basketball Jersey Team Canada Championship including Joel Anthony (Miami Heat) and Andy $250 Rautins (New York Knicks) It’s your choice! Superbowl Party, Birthday, Wedding, Anniversary etc. FRANCO FRESHY CORPORATE & Greater Toronto Enjoy catering at home or office from one of the top caterers A26 EVENT CATERING INC. $500 Area in Southern Ontario $1000 GIFT CERTIFICATE Over 60 pages of menu items are available online www.francofreshy.com A28 2 Tickets - March 31 2011 Yankee Stadium Opening day - New York Yankees vs Detroit Tigers $500 AUTOGRAPHED BASEBALL JERSEYS JUSTIN MORNEAU Limited Edition Custom B2 Minnesota Twins Justin Morneau $350 Jersey JUSTIN MORNEAU Limited Edition Custom B3 Minnesota Twins Justin Morneau $350 $ 350 Jersey LARRY WALKER WBC 06 World Baseball Classic Practice Jersey - B4 Team Canada Larry Walker $350 Red - #33 JOEY VOTTO WBC B6 09 World Baseball Classic Jersey - Red- Team Canada Joey Votto $350 $ -

Ohio High School Baseball Coaches Association State Clinic 2016

OHIO HIGH SCHOOL BASEBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION STATE CLINIC 2016 PREPARE FOR THE END JANUARY 21-23 HYATT REGENCY - Columbus HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES Irvin “Frosty” Brown, Bethel HS / Troy HS • John Cannizzaro, Newark Catholic HS Ken Ciolek, Lakewood HS • Glen Morse, New London HS • Greg Wilker, Milbury Lake HS INNOVATIVE PERFORMANCE The demands of the game are not the same for all players. We design each product with innovations to drive your preformance to the next level. Rawlings is the ball of choice for athletes who desire to be the best. PERFORMANCE MATTERS. RAWLINGS IS PROUD TO BE THE OFFICIAL BASEBALL OF THE OHIO HIGH SCHOOL BASEBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION. 4/%$'"+)(*,$'"((+ ('3,(-$+2 OHIO HIGH SCHOOL BASEBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION Dear OHSBCA Members, Welcome to the 65th annual OHSBCA State Clinic. You are a member of the 2nd largest coaches association in the United States. Many high school coaches and college speakers have said that this is one of the best clinics in the nation. I am hop- ing that you are able to take something from this year’s clinic and go back to your school to make the young men in your program better this coming year and for years to come. The theme for the 2016 clinic is “Prepare for the End” and it is my hope that all of you set your goals high and start preparing for your team to reach Huntington Park. My involvement on this board for the past 6 years has allowed me the opportunity to witness great improvements the association has made. It is my honor to give back as Director of the 2016 State Clinic. -

Ticket from the Toronto Round of the Classic at Rogers Centre Team 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E Canada 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 5 7 1 United

ticket from the Toronto round of the Classic at Rogers Centre Team 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 R H E Canada 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 5 7 1 United States 0 1 0 3 0 2 0 0 - 6 9 0 Pitchers of Record Win: LaTroy Hawkins (1-0) Loss: Mike Johnson (0-1) Save: J.J. Putz (1) Home Runs Canada: Joey Votto in 3rd inning, 1 RBI; Russell Martin in 7th inning, 1 RBI USA: Kevin Youkilis in 4th inning, 1 RBI; Brian McCann in 4th inning, 2 RBI; Adam Dunn in 6th inning, 2 RBI Umpires HP: Marvin Hudson (USA); 1B: Minoru Nakamura (Japan); 2B: Dan Iassogna (USA); 3B: Masami Yoshikawa (Japan) Time of Game: 2:55 Attendance: 42,314 The homers came fast and furious, as five players went deep for a combined 7 RBI in a 6-5 duel between two North American entries. Team Canada, playing host, sent seven batters to the plate in the first inning against Jake Peavy but only scored one time. C Russell Martin drew a one-out walk and DH Joey Votto singled him to third. 1B Justin Morneau grounded to first, scoring Martin. CF Jason Bay walked and DH Matt Stairs was hit by a pitch to load the bases for 3B Mark Teahen. Peavy threw 3 fastballs in a row past Teahen to escape the jam. In the bottom of the second, Team Canada veteran Mike Johnson walked 1B Kevin Youkilis and RF Adam Dunn to start the inning. -

Indians Complete 2013 First-Year Player Draft

INDIANS COMPLETE 2013 FIRST-YEAR PLAYER DRAFT CLEVELAND, OH - Information on Cleveland Indians 2013 First-Year Player Draft selections, rounds 1 thru 10. *Signed 6/15 Round 1 (#5 overall) OF CLINT FRAZIER AGE/DOB: 18, September 6, 1994 High School: Loganville HS (GA) BATS/THROWS: R/R HEIGHT/WEIGHT: 5-11/185 Prep outfielder, recently graduated from Loganville High School in Loganville, Georgia, where he batted .485 in his senior campaign (47-for-97) with 17 homers, 45 RBI, 56 runs scored, a .561 on-base pct. and a 1.134 slugging pct. in 32 games. Following the season, the 5’11” right-handed hitter was named the Gatorade National Baseball Player of the Year. He has a verbal commit to attend the University of Georgia and is the first overall high school position player selected in the 2013 draft. From MLB.com on Frazier Comments: Everything you say about Austin Meadows, you can say about Frazier, except for one thing: his size. Frazier doesn't "look the part" quite as much, but he still has just as many tools as his fellow Georgia prepster. A right-handed hitter, Frazier ran a 6.6 second 60 at the East Coast Pro Showcase over the summer. He also might have a more advanced bat than most of the high schoolers in the class, with a quick, short stroke that generates more power than you might expect given his frame. The lack of physicality might concern some, but his collection of tools should keep him high on Draft boards all spring.