World War II Warplanes As Cultural Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Did You Sleep Last Night?????

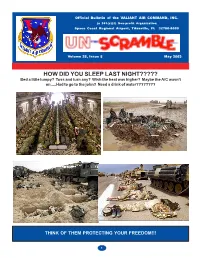

Official Bulletin of the VALIANT AIR COMMAND, INC. (a 501(c)(3) Non-profit Organization Space Coast Regional Airport, Titusville, FL 32780-8009 Volume 25, Issue 5 May 2003 HOW DID YOU SLEEP LAST NIGHT????? Bed a little lumpy? Toss and turn any? Wish the heat was higher? Maybe the A/C wasn't on.....Had to go to the john? Need a drink of water???????? THINK OF THEM PROTECTING YOUR FREEDOM!!! 1 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 6600 Tico Road, Titusville, FL 32780-8009 BOARD OF D IRECTORS MEETINGS Tel (321) 268-1941 FAX (321) 268-5969 MAY 13, 2003 EXECUTIVE STAFF 12:00 NOON VAC MUSEUM BOARD ROOM COMMANDER Lloyd Morris (386) 423-9304 JUNE 10, 2003 EXECUTIVE OFFICER Harold Larkin 12:00 NOON (321) 453-4072 VAC MUSEUM BOARD ROOM AIRSHOW DEBRIEF/MEMBERSHIP MEETING OPERATIONS OFFICER Mike McCann Email: [email protected] (321) 259-0587 MAY 17, 2003 12:00 NOON MAINTENANCE OFFICER Bob James VAC HANGAR (POTLUCK--PLEASE BRING YOU FAVORITE DISH. (321) 453-6995 VAC WILL PROVIDE ENTREE. CALL 268-1941 TO LET US KNOW YOU WILL ATTEND.) FINANCE OFFICER Pieter Lenie (321) 727-3944 PROCUREMENT - Bob Frazier PERSONNEL OFFICER Alice Iacuzzo (321) 799-4040 Things have been busy this month with meetings and the Easter holidays. However, the T-2C Buckeye arrived by truck on April TRANSP/FACILITY OFFICER Bob Kison 17. It was immediately unloaded by the in-resident crew and (321) 269-6282 attempts to reattach the wings were initiated. The crew will be identified and thanked next month following completion of these PROCUREMENT OFFICER Bob Frazier efforts. -

Manu Goswami Gabrielle Hecht Adeeb Khalid Anna Krylova

Manu Goswami Gabrielle Hecht Adeeb Khalid Anna Krylova Elizabeth F. Thompson Jonathan R. Zatlin Andrew Zimmerman AHR Conversation History after the End of History: Reconceptualizing the Twentieth Century PARTICIPANTS: MANU GOSWAMI,GABRIELLE HECHT,ADEEB KHALID, ANNA KRYLOVA,ELIZABETH F. THOMPSON,JONATHAN R. ZATLIN, AND ANDREW ZIMMERMAN Over the last decade, this journal has published eight AHR Conversations on a wide range of topics. By now, there is a regular format: the Editor convenes a group of scholars with an interest in the topic who, via e-mail over the course of several months, conduct a conversation that is then lightly edited and footnoted, finally appearing in the December issue. The goal has been to provide readers with a wide-ranging and accessible consideration of a topic at a high level of ex- pertise, in which participants are recruited across several fields. It is the sort of publishing project that this journal is uniquely positioned to take. The initial impulse for the 2016 conversation came from a Mellon Sawyer Seminar on “Reinterpreting the Twentieth Century,” held at Boston University in 2014–2015. That seminar, convened by Andrew Bacevich, Brooke Bower, Bruce Schulman, and Jonathan Zatlin, invited participants to “challenge our assump- tions about the twentieth century, its ideologies, debates, divides, and more,” in a broad-based effort to “create new chronologies and narratives that engage with our current hopes and struggles.”1 For the AHR, this is a departure from previous Conversation topics, in that it is chronologically bounded rather than thematically defined. That said, the Editor made a concerted effort to assemble a group of scholars working in myriad subfields and drawing on a diverse range of “area studies” paradigms (though no doubt many of them would reject that very con- cept). -

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631

Shelf List 05/31/2011 Matches 4631 Call# Title Author Subject 000.1 WARBIRD MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD EDITORS OF AIR COMBAT MAG WAR MUSEUMS OF THE WORLD IN MAGAZINE FORM 000.10 FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM, THE THE FLEET AIR ARM MUSEUM YEOVIL, ENGLAND 000.11 GUIDE TO OVER 900 AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS USA & BLAUGHER, MICHAEL A. EDITOR GUIDE TO AIRCRAFT MUSEUMS CANADA 24TH EDITION 000.2 Museum and Display Aircraft of the World Muth, Stephen Museums 000.3 AIRCRAFT ENGINES IN MUSEUMS AROUND THE US SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION LIST OF MUSEUMS THROUGH OUT THE WORLD WORLD AND PLANES IN THEIR COLLECTION OUT OF DATE 000.4 GREAT AIRCRAFT COLLECTIONS OF THE WORLD OGDEN, BOB MUSEUMS 000.5 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE LIST OF COLLECTIONS LOCATION AND AIRPLANES IN THE COLLECTIONS SOMEWHAT DATED 000.6 VETERAN AND VINTAGE AIRCRAFT HUNT, LESLIE AVIATION MUSEUMS WORLD WIDE 000.7 NORTH AMERICAN AIRCRAFT MUSEUM GUIDE STONE, RONALD B. LIST AND INFORMATION FOR AVIATION MUSEUMS 000.8 AVIATION AND SPACE MUSEUMS OF AMERICA ALLEN, JON L. LISTS AVATION MUSEUMS IN THE US OUT OF DATE 000.9 MUSEUM AND DISPLAY AIRCRAFT OF THE UNITED ORRISS, BRUCE WM. GUIDE TO US AVIATION MUSEUM SOME STATES GOOD PHOTOS MUSEUMS 001.1L MILESTONES OF AVIATION GREENWOOD, JOHN T. EDITOR SMITHSONIAN AIRCRAFT 001.2.1 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE BRYAN, C.D.B. NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM COLLECTION 001.2.2 NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE MUSEUM, THE, SECOND BRYAN,C.D.B. MUSEUM AVIATION HISTORY REFERENCE EDITION Page 1 Call# Title Author Subject 001.3 ON MINIATURE WINGS MODEL AIRCRAFT OF THE DIETZ, THOMAS J. -

Brochure Brooks Montage.Qxd

Brochure Brooks_Montage.qxd 06.06.2007 12:53 Uhr Seite 1 Brochure Brooks_Montage.qxd 06.06.2007 12:53 Uhr Seite 2 Brochure Brooks_Montage.qxd 06.06.2007 12:53 Uhr Seite 3 einz Krebs was raised and lives in Southern His originals, limited fine art print editions, and other H Germany where he spends most of his free high quality collector's items are sought after all over time either flying or painting. the world. Heinz’s fine art print editions have been authenticated and further enhanced by the personal He is a passionate aviator, a commercial- and test signatures of many of the world's most historically pilot, as well as a flying instructor with more than significant aviators. 10,000 hours of flying time and almost 22,000 landings to his credit. Heinz has flown 81 different types of This artist has been blessed with a stunning natural powered aircraft ranging from Piper Cubs to jet talent, his ability is simply breathtaking. The one fighters and 39 different glider aircraft models. thing, however, which has always fascinated the early bird Heinz Krebs was to combine his two most-loved But all his life he has had one other love besides his activities in life, and create: Aviation Art. flying – fine arts, especially painting in oils. What makes his aviation art so unique is that, being able to draw on his life-long experience of both subjects, Heinz is able to convey true portraits of flight full of romance, action, and drama. Brochure Brooks_Montage.qxd 06.06.2007 12:53 Uhr Seite 4 eavy stock, acid-free paper. -

TRAVEL PLANNER You Don't Have to Cross an Ocean to Discover America's World War II Heritage and History

SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTION WWIIAMERICA IN The War • The Home Front • The People 2014 ANNUAL WORLD WAR II TRAVEL PLANNER You don't have to cross an ocean to discover America's World War II heritage and history. It's right here, at amazing museums and historical sites like these. AAAAAAAAAAA Air Zoo The Air Zoo, rated a “Gem” by AAA, is a destination attraction dedicated to showcasing the history of aviation. The Air Zoo features more than 50 rare and historic aircraft, many of which flew during World War II, including the Curtiss P-40 Warhawk, the Bell P-39 Airacobra, the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt and the Lockheed P-38 Lightning. The Air Zoo also offers indoor amusement park-style rides, a 4-D theater, full-motion flight simulators and Space: Dare to Dream, an interactive exhibit exploring the discovery of space. Location: 6151 Portage Road, Portage, MI 49002 Contact Info: 269-382-6555, 866-524-7966 (Toll Free) Hours: Mon.–Sat. 9-5, Sun. noon–5. Closed Thanks- giving, Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. Cost: General admission $10 at door; Kids 4 & under are free. Wristband packages and individual tickets are available for rides and attractions. For more information: www.airzoo.org SPECIAL ADVERTISING SECTION Museum of THE AMERICAN G.I. COLLEGE STATION, TEXAS Open House 2014 • March 21–22 • Living History Event The Largest Military Vehicle Rally and Reenactment in the South! • Militaria Flea Market • Vehicle and Period Displays Liberty Ship Both Days: Open to the public at 9 AM WWII Battle Reenactment on Saturday at 3 PM JOHN W. -

Arctic Discovery Seasoned Pilot Shares Tips on Flying the Canadian North

A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT SEPTEMBER 2019 • VOLUME 13, NUMBER 9 • $6.50 Arctic Discovery Seasoned pilot shares tips on flying the Canadian North A MAGAZINE FOR THE OWNER/PILOT OF KING AIR AIRCRAFT King September 2019 VolumeAir 13 / Number 9 2 12 30 36 EDITOR Kim Blonigen EDITORIAL OFFICE 2779 Aero Park Dr., Contents Traverse City MI 49686 Phone: (316) 652-9495 2 30 E-mail: [email protected] PUBLISHERS Pilot Notes – Wichita’s Greatest Dave Moore Flying in the Gamble – Part Two Village Publications Canadian Arctic by Edward H. Phillips GRAPHIC DESIGN Rachel Wood by Robert S. Grant PRODUCTION MANAGER Mike Revard 36 PUBLICATIONS DIRECTOR Jason Smith 12 Value Added ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Bucket Lists, Part 1 – John Shoemaker King Air Magazine Be a Box Checker! 2779 Aero Park Drive by Matthew McDaniel Traverse City, MI 49686 37 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 Fax: (231) 946-9588 Technically ... E-mail: [email protected] ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATIVE COORDINATOR AND REPRINT SALES 22 Betsy Beaudoin Aviation Issues – 40 Phone: 1-800-773-7798 E-mail: [email protected] New FAA Admin, Advertiser Index ADVERTISING ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT PLANE Act Support and Erika Shenk International Flight Plan Phone: 1-800-773-7798 E-mail: [email protected] Format Adopted SUBSCRIBER SERVICES by Kim Blonigen Rhonda Kelly, Mgr. Kelly Adamson Jessica Meek Jamie Wilson P.O. Box 1810 24 Traverse City, MI 49685 1-800-447-7367 Ask The Expert – ONLINE ADDRESS Flap Stories www.kingairmagazine.com by Tom Clements SUBSCRIPTIONS King Air is distributed at no charge to all registered owners of King Air aircraft. -

Presidential State Funerals: Past Practices and Security Considerations

INSIGHTi Presidential State Funerals: Past Practices and Security Considerations Updated December 3, 2018 On November 30, 2018, former President George H.W. Bush died. In the tradition of past presidential deaths, President Bush will receive a state funeral (designated as a National Special Security Event), which includes several ceremonial events in Washington, DC, prior to his burial at the George H.W. Bush Presidential Library Center at Texas A&M University in College Station, TX. The state funeral process is carried out by the Joint Task Force-National Capital Region, a division of the Military District of Washington (MDW). The official schedule for President Bush’s state funeral is available from MDW’s website. Presidential State Funerals According to the MDW, a state funeral is “a national tribute which is traditionally reserved for a head of state” and is conducted “on behalf of all persons who hold, or have held, the office of president….” In total, nine Presidents (not including President George H.W. Bush) have been honored with a state funeral. Prior to President Bush’s death, the last state funeral occurred for President Gerald Ford. For more resources on presidential funerals, see CRS Report R45121, Presidential Funerals and Burials: Selected Resources, by Maria Kreiser and Brent W. Mast. Presidential Proclamation To initiate a state funeral, the President traditionally issues a proclamation to announce the former President’s death, authorize the MDW to begin the state funeral process, order flags to fly at half-staff, and declare a national day of mourning. President Trump’s proclamation was issued on December 1, 2018. -

Of the 90 YEARS of the RAAF

90 YEARS OF THE RAAF - A SNAPSHOT HISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia, or of any other authority referred to in the text. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 90 years of the RAAF : a snapshot history / Royal Australian Air Force, Office of Air Force History ; edited by Chris Clark (RAAF Historian). 9781920800567 (pbk.) Australia. Royal Australian Air Force.--History. Air forces--Australia--History. Clark, Chris. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Office of Air Force History. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. 358.400994 Design and layout by: Owen Gibbons DPSAUG031-11 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence PO Box 7935 CANBERRA BC ACT 2610 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Chief of Air Force Foreword Throughout 2011, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has been commemorating the 90th anniversary of its establishment on 31 March 1921. -

Index Des Auteurs Auteur >> Numéro/Page

Index des Auteurs http://www.aero-index.com/ Editions Larivière - Fanatique de l'Aviation Auteur >> Numéro/Page - Article Akary Frédéric ... Alex Trados -suite- 471/36 - Au sommet des cimes 130/63 - Le Fieseler 103 Reichenberg 143/70 - Messer 163 Anton (conversion) Alain Trados 131/63 - Le Me 163 (modifié en biplace) Allen Richard / Vincent Carl / Beauchamp Gérard 307/16 - Le Grumman / CCF G-23 Alegi Gregory 263/7 - Le Musée Caproni ouvrira au printemps Aloni Shlomo 267/6 - Un Macchi C.202 sort d'atelier 294/8 - Les Super Frelon israéliens au musée 278/6 - Le musée Caproni a réouvert ses portes 298/22 - Les deux guerres des Dassault Ouragan 360/7 - Un Bf 109 G-4 restauré en Italie 311/12 - Des Mystère contre des MiG 360/8 - Le Musée de la Force aérienne italienne rouvre... 312/61 - Des Mystère contre des MiG 363/11 - L'Arabie Saoudite offre un écrin à ses avions... 332/12 - Les Vautour en Israël 384/5 - L'Italie aura bientôt son Fiat CR.42 333/40 - Les Vautour en Israël 385/9 - Le SPAD VII du musée de la force aérienne... 334/50 - Les Vautour en Israël 391/7 - Le musée de la force aérienne italienne expose... 336/12 - De Sambad à Sa'ar 438/36 - Avant après 346/12 - L'épopée du Mirage III en Israël 446/7 - Rare trio de Ca.100 à Trente 347/50 - L'épopée du Mirage III en Israël 446/11 - Un premier Ro.37 afghan de retour en Italie 348/40 - L'épopée du Mirage III en Israël 452/10 - Le musée de la Force aérienne italienne expose.. -

VA Vol 18 No 8 Aug 1990

STRAIGHT AND LEVEL > € 8 of the problem and solved the man's will all do our best to pass along the o :::; dilemma. excitement and satisfaction of coming Q'" I've had calls from people on cross- to Oshkosh, helping out where we could countries who have developed and learning the many lessons to be by Espie "Butch" Joyce problems with unusual engines such as, learned about people as well as for instance, a Warner and asked if I airplanes. They will all say how hard it might know a mechanic in the area is to believe everything and that they familiar with the type. Sometimes I can simply must get to Oshkosh next year. help, sometimes I can refer them to We need to continue to tell everyone With this issue of VINTAGE another member who can. It's another how fantastic the EAA Oshkosh ex AIRPLANE EAA Oshkosh '90 will be example of how we at the A/C Di vision perience is and tell everyone to ex history. The Antique/Classic Division are better off as a group rather than as perience it for themselves. If we will have hosted more than 800 classics individuals. continue to pass the word and unite our and 120 antiques. All of this activity A viation people are unique. They selves, we stand a better chance of will have been administered by volun trot off to the airport at every oppor retaining the freedoms we now enjoy in teer help. It's a monumental undertak tunity while their friends are going to personal flight. -

WPS Handbook 2013-14

POSTGRADUATE MODULE HANDBOOK Department of Politics, Birkbeck, University of London WAR, POLITICS AND SOCIETY Dr Antoine Bousquet [email protected] Introduction Module Aims and Objectives War, Politics and Society aims to provide students with an advanced understanding of the role of war in the modern world. Drawing on a wide range of social sciences and historiographical sources, its focus will be on the complex interplay between national, international and global political and social relations and the theories and practices of warfare since the inception of the modern era and the ‘military revolution’ of the sixteenth century. The module will notably examine the role of war in the emergence and development of the nation-state, the industrialisation and modernisation of societies and their uses of science and technology, changing cultural attitudes to the use of armed force and martial values, and the shaping of historical consciousness and collective memory. Among the contemporary issues addressed are the ‘war on terror’, weapons of mass destruction, genocide, humanitarian intervention, and war in the global South. Students completing the module will: • be able to evaluate and critically apply the central literatures, concepts, theories and methods used in the study of the relations between war, politics and society; • demonstrate balanced, substantive knowledge of the central debates within war studies; • be capable of historically informed, critical analysis of current political and strategic debates concerning the use of armed force; • be able to obtain and analyse relevant information on armed forces and armed conflict from a wide array of governmental, non-governmental, military and media sources; • have developed transferable skills, including critical evaluation, analytical investigation, written and oral presentation and communication. -

Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame 6151 Portage Rd

Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame 6151 Portage Rd. Portage, MI 49002 Ph: 269.350.2812 Fax: 269.382.1813 Email: [email protected] Dear Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame Elector, Thank you for your interest in the election of the 2019 Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame (MAHOF) enshrinees. You are receiving this ballot because you are a member of the Air Zoo and/or: have been enshrined in the MAHOF, have been selected by the MAHOF Advisory Panel as an appointed elector, or are a member of the MAHOF Advisory Panel. The next enshrinement ceremony will take place at the Air Zoo’s Science Innovation Hall of Fame Awards Gala on Saturday, April 13, 2019. Please read the following very carefully before you cast your votes: Candidates are divided into two groups. Group I candidates are deceased. Group II candidates are living. To help you cast your votes, brief biographies of the nominees in each group follow the lists of names. Once your decisions are made, please cast your votes for the MAHOF enshrinees by following the submission instructions at the bottom of the ballot on the next page. Because the number of First-, Second-, and Third-place votes is often needed to break ties in ballot counting, it is critical that you vote for three candidates in each group. Ballots without three votes per group will not be counted. For questions, contact the Hall of Fame Advisory Panel via email at [email protected]. Ballots must be received by January 26, 2019. Thank you very much for your participation in this process! Through the Michigan Aviation Hall of Fame, you help preserve this state’s rich aviation and space history.