Demolition-By-Neglect: Where Are We Now?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination of Historic Building, Structure, Site, Or Object

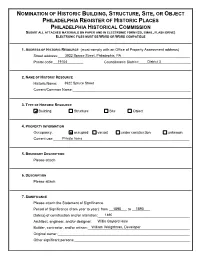

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3920 Spruce Street, Philadephia, PA ________ Postal code:_______________ 19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________ District 3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________ 3920 Spruce Street ________ Current/Common Name:________House___________________________________________________ of Our Own Book Store 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________ Bookstore ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach 6. DESCRIPTION Please attach 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1890 to _________1924 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________ 1890 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:_________________________________________________ Willis Gaylord Hale Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________William Weightman, Developer _________ -

Tenth Annual Endangered Properties List

SP PRESERVATION ECIAL ISSU MATTERS E The Newsletter of The Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia Tenth Annual Endangered Properties List Logan Square u Police Administration Building u District Health Center No. 1 u Philadelphia Breweries Carver Court u Federal Historic Tax Credits Logan Square EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S Philadelphia MESSAGE SIGNIFICANCE Logan Square is home to the greatest concentration of civic architecture in Phila- delphia. Among its grandest buildings are the Free Library of Philadelphia (Horace Trumbauer, 1925) and the Family Court Building (John T. Windrim, 1941), twin Beaux Arts palaces modeled after the or the last ten years, the Preservation Place de la Concorde in Paris. The symmetry of these buildings opposite Swann Fountain is one of Alliance has published a year-end the most picturesque and character-defining elements of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Flist of endangered properties found across Philadelphia and the region. This year, THREAT With construction of a new Family Court facility now underway, the City of Philadelphia for the first time, we’re also featuring an endan- will be inviting proposals from private developers to repurpose the Family Court Building. The most gered policy: the Federal Historic Tax Credit. likely new use is a hotel. The parcel’s zoning allows for developments up to 150 in height, which could The tax credit program is probably the most invite proposals to build on top of the existing building. Though Family Court and its interiors are important financial tool for preserving historic protected by listing on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, designation alone is not likely to buildings in the country. -

1430-N-Broad-St-Nomination.Pdf

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM ON CD (MS WORD FORMAT) 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________1430 N Broad St ________ Postal code:_______________19121 Councilmanic District:_______________5 ___________ 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________Charles E. Ellis house ________ Common Name:_________________________________________________________Palace/Unity Mission ________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Condition: excellent good fair poor ruins Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:________unknown____________________________________________________ ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See attached. 6. DESCRIPTION See attached. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1890 to _________1909 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________1890-91 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________William H. Decker _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________ _________ Original owner:_________________________________________________________Charles -

The Wright Brothers' Drive for the Sky from Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms National Register of Historic Places FIRST WORD Reaffirmation

PRESERVING OUR NATION'S HERITAGE FALL 2003 Wings The Wright Brothers' Drive for the Sky From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms National Register of Historic Places FIRST WORD Reaffirmation BY DE TEEL PATTERSON TILLER RECENTLY I MET WITH a small delegation from the Coalition of land tangible and accessible, IT REMAINS TO BE SEEN whether the Q/II Families—survivors and families and friends of those killed Coalition will be successful. New York City politics is a no-holds- in the attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. barred contact sport and much is at stake in the redevelopment of By their count their membership numbers around 3,000— the World Trade Center site. I hold out the hope that it may be roughly the same as lost that dark day more than two years ago. possible to find some compromise that preserves the remnants of The group's journey to Washington, DC, was borne of an inter the towers so that 100 or 1,000 years from now, Americans of est in seeing the remains of the towers designated as a National those generations will be able to walk over the bedrock and forge Historic Landmark. The putative leader of the delegation was a their own connections with this event that so changed our lives at young, purposeful man, Anthony Gardner, whose older brother, the beginning of the 21st century. Harvey Joseph Gardner, died in the collapse of the North Tower, THE MEETING WAS DIFFICULT and, at times, heart wrench ing. Everyone had a story making the tragedy compelling in mm We do what no book, television show, ways the media never could. -

Moyamensing / Passyunk & Northern Liberties / Spring Garden

ARCHITECTURAL RESEARCH AND CULTURAL HISTORY HISTORIC PRESERVATION CONSULTING HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT FOR NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER 3 2009-2010 INTRODUCTION HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT FOR NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER 3 PHILADELPHIA CITY PLANNING DISTRICT 1 NORTHERN AND SOUTHERN AREAS: MOYAMENSING AND PASSYUNK (NORTHERN PART) AND NORTHERN LIBERTIES AND SPRING GARDEN EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY EMILY T. COOPERMAN, PH.D. Cluster 3 consists of two portions of Philadelphia immediately to the south and north of the city’s original incorporated boundaries of South Street and Vine Street lying within the City of Philadelphia’s Planning District 1 (figure 1) and exclusive of the areas included in existing historic districts. The northern study area is bounded on the south by Vine Street, by the Delaware River on the east, and Poplar Street and Girard Avenue on the north, and by Fairmount Park and the Parkway (which are contained in existing National Register Historic districts) on the west. This area corresponds to the early nineteenth century districts of Northern Liberties and Spring Garden in the former Philadelphia County before the 1854 Consolidation. The southern study area corresponds to the northernmost areas of the city’s eighteenth and early nineteenth century districts of Moyamensing and Passyunk (before the reconfiguration of these districts in 1848), and is bounded on the north by South Street, on the west by the Schuylkill River, on the south by Washington Avenue and Christian Street, and on the east by 6th Street, and excludes the former district of Southwark because that has been included in a National Register of Historic Places District. Figure 1: Philadelphia Planning District 1 1 ARCHITECTURAL RESEARCH AND CULTURAL HISTORY HISTORIC PRESERVATION CONSULTING HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT FOR NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER 3 2009-2010 INTRODUCTION In addition to those National Register of Historic Places and City of Philadelphia Historic Districts that border the study areas, these areas contain a number of other listed and eligible historic districts. -

On Track Progress Towards Transit-Oriented Development in The

Created in 1965, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) is an interstate, intercounty and intercity agency that provides continuing, comprehensive and coordinated planning to shape a vision for the future growth of the Delaware Valley region. The region includes Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery counties, as well as the City of Philadelphia, in Pennsylvania; and Burlington, Camden, Gloucester and Mercer counties in New Jersey. DVRPC provides technical assistance and services; conducts high priority studies that respond to the requests and demands of member state and local governments; fosters cooperation among various constituents to forge a consensus on diverse regional issues; determines and meets the needs of the private sector; and practices public outreach efforts to promote two-way communication and public awareness of regional issues and the Commission. Our logo is adapted from the official DVRPC seal, and is designed as a stylized image of the Delaware Valley. The outer ring symbolizes the region as a whole, while the diagonal bar signifies the Delaware River. The two adjoining crescents represent the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and the State of New Jersey. DVRPC is funded by a variety of funding sources including federal grants from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and Federal Transit Administration (FTA), the Pennsylvania and New Jersey departments of transportation, as well as by DVRPC’s state and local member governments. The authors, however, are solely responsible for its findings and conclusions, which may not represent the official views or policies of the funding agencies. DVRPC fully complies with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and related statutes and regulations in all programs and activities. -

Dense and Visually Stimulating, Downtown Philadelphia Bustles with Shoppers, Business- People, and Day-Trippers. Musicians Raise

CG Fall 03 Fn3.cc 12/8/03 8:06 PM Page 44 70 years THE HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY2003 fleetingstreets THE PLIGHT AND PROMISE OF NORTH PHILADELPHIA BY BRIAN D. JOYNER PHOTOGRAPHS BY JOSEPH ELLIOTT Dense and visually stimulating, downtown Philadelphia bustles with shoppers, business- people, and day-trippers. Musicians raise the spirits of passersby with impromptu concerts on street corners. Hotels, restaurants, specialty shops, and gourmet outlets crowd the streets. Center City—as the downtown district is known—caters to the young middle class and empty-nesters eager to take advantage of Philadelphia’s new energy. Everywhere, it seems, are signs pointing out the city’s legendary connection to a nascent America. It is not hard to convince people of the importance of Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, or the Betsy Ross House. It is Philadelphia’s other history, in another part of town, that needs civic and economic bolstering. Opposite: Boys on Diamond Street in North Philadelphia, a fashionable address in the 19th century. Most of the row houses are still in good shape. 44 COMMON GROUND FALL 2003 CG Fall 03 Fn3.cc 12/12/03 8:12 AM Page 45 COMMON GROUND FALL 2003 45 CG Fall 03 Fn3.cc 12/10/03 8:27 PM Page 46 46 COMMON GROUND FALL 2003 CG Fall 03 Fn3.cc 12/10/03 8:27 PM Page 47 In North Philadelphia, there is no saxophone music to brighten the afternoon, no Philadelphia’s Urban Legacy signs trumpeting the neighborhood’s rich past or directing visitors to trendy shops Between 1875 and 1900, North Phila- and historic sites. -

View Nomination

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3920 Spruce Street, Philadephia, PA ________ Postal code:_______________ 19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________ District 3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________ 3920 Spruce Street ________ Current/Common Name:________House___________________________________________________ of Our Own Book Store 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________ Bookstore ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach 6. DESCRIPTION Please attach 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1890 to _________1924 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________ 1890 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:_________________________________________________ Willis Gaylord Hale Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________William Weightman, Developer _________ -

1946 N. 23Rd Street Postal Code: 19121

1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address: 1946 N. 23rd Street Postal code: 19121 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name: Pearl Bailey House Current Name: 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Condition: excellent good fair poor ruins Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use: Residential 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach a narrative description and site/plot plan of the resource’s boundaries. 6. DESCRIPTION Please attach a narrative description and photographs of the resource’s physical appearance, site, setting, and surroundings. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach a narrative Statement of Significance citing the Criteria for Designation the resource satisfies. Period of Significance (from year to year): 1882; c. 1935-1970 Date(s) of construction: 1882 Architects: Willis G. Hale, architect Builders: Original owner: William M. Singerly, developer Significant person: Pearl Bailey, actress/singer CRITERIA FOR DESIGNATION: The historic resource satisfies the following criteria for designation (check all that apply): (a) Has significant character, interest or value as part of the development, heritage or cultural characteristics of the City, Commonwealth or Nation or is associated with the life of a person significant in the past; or, (b) Is associated with an event of importance to the history of the City, Commonwealth or Nation; or, (c) Reflects the environment in an era characterized by a distinctive -

Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority 1234 Market

PHILADELPHIA REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY 1234 MARKET STREET, 16TH FLOOR PHILADELPHIA, PA 19107 BOARD MEETING WEDNESDAY, JULY 08, 2015 Open Session – 4:00 P.M. A G E N D A APPROVAL OF BOARD MINUTES (a) Meeting of June 10, 2015 (b) Special Board Meeting of June 26, 2015 I. ADMINISTRATIVE Page (a) Philadelphia Home Improvement Loan (1) Redeem Outstanding Bonds and Sell Loan Portfolio (b) School District of Philadelphia (5) Edwin M. Stanton Elementary School Cafeteria NTI Grant Agreement II. DEVELOPMENT 1603 N. 33rd Street (8) A Honey Clark Company LLC, Walter M. McClanahan, Principle NTI Funding in the Amount of $75,000 Facilitating the Amicable Acquisition of 1603 N. 33rd Street III. HOUSING FINANCE / NSP Blumberg Apartments Phase 1 LP (12) PHA Scattered Sites Non-Recourse Construction/Permanent Loan Agreement AGENDA Board Meeting of July 8, 2015 Page -2- IV. REAL ESTATE Vacant Property Review Committee (26) Conveyance of Properties V. ADD ON ITEM Page Morton Urban Renewal Area (1) 131-35 E. Rittenhouse Street Conveyance of Property to School District of Philadelphia PHILADELPHIA REDEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY BOARD MEETING MINUTES A meeting of the Board of Directors of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority was held on Wednesday, June 10, 2015 commencing at 4:10 p.m. in the offices of the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, being its regular meeting place, 16th floor, 1234 Market Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, pursuant to proper notices. ROLL CALL The following members of the Board of Directors reported present: James Cuorato, Chairman; Beverly Coleman, Secretary; and Rob Dubow, Treasurer and. The following members of the Board of Directors not present: Jennifer Rodriguez, Vice Chairman and Alan Greenberger, 2nd Vice Chair. -

3922-Spruce-St-Nomination.Pdf

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3922 Spruce Street, Philadephia, PA ________ Postal code:_______________ 19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________ District 3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________ 3922 Spruce Street ________ Current/Common Name:___________________________________________________________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________ Private home ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach 6. DESCRIPTION Please attach 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________ 1890 to _________ 1890 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________ 1890 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:_________________________________________________ Willis Gaylord Hale Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________William Weightman, Developer _________ Original owner:_________________________________________________________