A/HRC/13/39/Add.5 General Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publikationen

S C H R I F T E N V E R Z E I C H N I S* L I S T OF P U B L I C A T I O N S** M A N F R E D N O W A K Juni 2016 1973 1. Die soziale Verantwortung der Werbewirtschaft, Abschlußarbeit im Rahmen des Hochschullehrgangs für Werbung und Verkauf an der Hochschule für Welthandel Wien, 40 Seiten 1974 2. Besonderes Verwaltungsrecht (gemeinsam mit Felix Ermacora), 3-teiliges Skriptum, veröffentlicht von der österreichischen Hochschülerschaft, 505 Seiten 3. Natural Law and Legal Positivism, Seminararbeit New York, 32 Seiten 4. Torture - some reflections on an alarming phenomenon, thesis New York, 100 Seiten * Diese chronologische Liste enthält neben wissenschaftlichen Aufsätzen und Büchern auch journalistische und einzelne nicht-veröffentlichte Arbeiten. fett = Selbständige Arbeiten (Bücher, Forschungsberichte, Konferenzberichte) kursiv = Wichtigere unselbständige Arbeiten (Artikel in Zeitschriften, Festschriften etc.) unterstrichen = Expertenberichte an internationale Organisationen ** This chronological list contains in addition to academis articels and books also some more journalistic or non – published papers. bold = Independent works (books, research or expert reports) italics = Major articles in periodicals or books underscored = Expert reports to international organizations 1975 5. The Role of Third Parties - comparative analysis of the party system in the U.S. and Austria, Seminararbeit New York, 42 Seiten 6. Land Reform in Latin America, Master's thesis New York, 91 Seiten 7. Seenverkehrsordnung und Umweltschutz, ZVR 1975, 161- 169 1976 8. Weitreichende Konsequenzen des 1. VfGH-Erkenntnises zum Rundfunkgesetz (insbes für den Justizverwaltungsbegriff), JBl 1976, 529-532 9. Lärmbericht für Wien (Mitarbeit als Konsulent), herausgegeben vom Institut für Stadtforschung, 129 Seiten 1977 10. -

The Right to Heal U.S

The Right to Heal U.S. Veterans and Iraqi Organizations Seek Accountability for Human Rights and Health Impacts of Decade of U.S.-led War Preliminary Report Submitted in Support of Request for Thematic Hearing Before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights 149th Period of Sessions Supplemented and Amended Submitted by The Center for Constitutional Rights on behalf of Federation of Workers Councils and Unions in Iraq Iraq Veterans Against the War Organization of Women’s Freedom in Iraq Acknowledgments This report was prepared by Pam Spees, Rachel Lopez, and Maria LaHood, with the assistance of Ellyse Borghi, Yara Jalajel, Jessica Lee, Jeena Shah, Leah Todd and Aliya Hussain. We are grateful to Adele Carpenter and Drake Logan of the Civilian-Soldier Alliance who provided invaluable research and insights in addition to the testimonies of servicemembers at Fort Hood and to Sean Kennedy and Brant Forrest who also provided invaluable research assistance. Deborah Popowski and students working under her supervision at Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic contributed early research with regard to the framework of the request as well as on gender-based violence. Table of Contents Submitting Organizations List of Abbreviations and Acronyms I. Introduction: Why This Request? 1 Context & Overview of U.S.’s Decade of War and Its Lasting Harms to Civilians and Those Sent to Fight 2 U.S.’s Failure / Refusal to Respect, Protect, Fulfill Rights to Life, Health, Personal Security, Association, Equality, and Non-Discrimination 2 Civilian -

The North Carolina Connection to Extraordinary Rendition and Torture January 2012

The North Carolina Connection To Extraordinary Rendition and Torture January 2012 Endorsed By: Prof. Martin Scheinin, JD Senator Dick F. Marty, JD Prof. Manfred Nowak, LL.M. United Nations Special Rapporteur on Dr jur. Consigliere agli Stati United Nations Special Rapporteur the Promotion and Protection of Human Member and former presi- on Torture, 2004-Oct. 2010 Rights and Fundamental Freedoms While dent of the Committee on Professor for International Law Countering Terrorism Professor of Public Legal Affairs and Human and Human Rights International Law European University Rights, Council of Europe Director, Ludwig Boltzmann Institute Parliamentary Assembly, Institute of Human Rights Villa Schifanoia, Via Boccaccio 121 Vice-President of the World University of Vienna I-50133 Florence, Italy Organisation Against Torture Freyung 6 CP 5445, 6901 Lugano A-1010 Vienna, Austria Switzerland Researched and prepared Deborah M. Weissman, Reef C. Ivey II Distinguished Professor of Law, University of North Carolina School of Law, and law students Kristin Emerson, Paula Kweskin, Catherine Lafferty, Leah Patterson, Marianne Twu, Christian Ohanian, Taiyyaba Qureshi, and Allison Whiteman, Immigration & Human Rights Policy Clinic, UNC School of Law Letter of Endorsement for the Report entitled The North Carolina Connection to Extraordinary Rendition and Torture I hereby submit this letter of endorsement for the Report entitled The North Carolina Connection to Extraordinary Rendition and Torture. The U.S. program of extraordinary rendition, which included forced disappearances, secret detention, and torture, violated the terms of the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights— legally binding treaty provisions that may not be derogated from under any circumstances. -

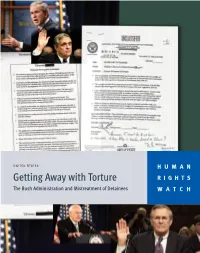

Getting Away with Torture RIGHTS the Bush Administration and Mistreatment of Detainees WATCH

United States HUMAN Getting Away with Torture RIGHTS The Bush Administration and Mistreatment of Detainees WATCH Getting Away with Torture The Bush Administration and Mistreatment of Detainees Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-789-2 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org July 2011 ISBN: 1-56432-789-2 Getting Away with Torture The Bush Administration and Mistreatment of Detainees Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ............................................................................................................ 12 I. Background: Official Sanction for Crimes against Detainees .......................................... 13 II. Torture of Detainees in US Counterterrorism Operations ............................................... 18 The CIA Detention Program ....................................................................................................... -

Manfred Nowak

ICC-02/17-81-Anx3 15-10-2019 1/6 NM PT OA OA2 OA3 OA4 MANFRED NOWAK SECRETARY GENERAL, GLOBAL CAMPUS OF HUMAN RIGHTS, VENICE PROFESSOR OF INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS, UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA INDEPENDENT EXPERT LEADING THE UNITED NATIONS GLOBAL STUDY ON CHILDREN DEPRIVED OF LIBERTY EDUCATION 1986 DR. HABIL OF CONSTITUTIONAL LAW (U NIVERSITY OF VIENNA ) 1975 LL.M (C OLUMBIA UNIVERSITY NEW YORK ) 1973 DR. IURIS (U NIVERSITY OF VIENNA ) OTHER FUNCTIONS since 2016 MEMBER OF THE ADVISORY BOARD OF THE EUROPEAN FORUM ALPBACH since 2012 SCIENTIFIC DIRECTOR OF THE VIENNA MASTER OF ARTS IN HUMAN RIGHTS , UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA since 2012 MEMBER OF THE OMV (INTERNATIONAL OIL AND GAS COMPANY ) ADVISORY BOARD FOR RESOURCEFULNESS since 2011 MEMBER OF THE ADVISORY BOARD OF THE EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR CONSTITUTIONAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS (ECCHR ), BERLIN since 2010 VICE -PRESIDENT OF THE AUSTRIAN UNESCO COMMISSION since 1995 MEMBER AND HONORARY MEMBER OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF JURISTS (ICJ ), GENEVA ICC-02/17-81-Anx3 15-10-2019 2/6 NM PT OA OA2 OA3 OA4 since 1992 MEMBER OF THE BOARD /A DVISORY BOARD OF THE ASSOCIATION FOR THE PREVENTION OF TORTURE (APT ), GENEVA FORMER RELEVANT EXPERIENCE 1992-2019 FOUNDER AND SCIENTIFIC DIRECTOR OF THE LUDWIG BOLTZMANN INSTITUTE OF HUMAN RIGHTS 2014-2018 HEAD OF THE INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH CENTRE HUMAN RIGHTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA 2016-2017 CHAIR OF AN INTERNATIONAL REVIEW COMMITTEE ON THE INTERNATIONAL COVENANT ON CIVIL AND POLITICAL RIGHTS (ICCPR ) APPOINTED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF TAIWAN 2012-2017 VICE CHAIR OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD OF THE EU AGENCY FOR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS (FRA ), VIENNA 1998-2016 AUSTRIAN NATIONAL DIRECTOR REPRESENTING THE UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA IN THE EMA (E UROPEAN MASTER DEGREE IN HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATISATION ) PROGRAMME , appointed by the Rector of the University of Vienna • EMA, based in Venice, was initiated by the European Commission and is jointly organized by 41 European Universities. -

Manfred Nowak

MANFRED NOWAK LUDWIG BOLTZMANN INSTITUTE OF HUMAN RIGHTS Freyung 6, 1. Hof, Stiege 2, 1010 VIENNA, AUSTRIA TEL: (+43) 1 4277 27456 E-MAIL: [email protected] GENERAL Born 26 June 1950 in Bad Aussee Nationality Austrian EDUCATION 1986 DR. HABIL OF CONSTITUTIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA 1975 LL.M COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY NEW YORK 1973 DR. IURIS UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA PRESENT FUNCTIONS since 2007 UNIVERSITY CHAIR FOR INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW Established in 2007 at the University of Vienna, Faculty of Law, Department for European, International and Comparative Law; Funded by OMV, the Austrian National Bank, Berndorf AG, Raiffeisen Central Bank, and Hermann and Marianne Straniak-Foundation. since 2004 U.N. SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON TORTURE AND OTHER CRUEL, INHUMAN OR DEGRADING TREATMENT Fact-finding missions to China, Nepal, Mongolia, Georgia, Jordan and Paraguay; joint report on Guantánamo Bay; Reports to the UN General Assembly and Human Rights Council. since 2000 HEAD OF AN INDEPENDENT HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION AT THE AUSTRIAN MINISTRY OF INTERIOR The Commission carries out preventive visits to places of police detention and controls the use of force by Austrian law enforcement personnel; It reports to the Human Rights Advisory Board of the Ministry; Mandate until 2008. since 2000 EMA CHAIRPERSON The European Masters Degree in Human Rights and Democratisation (EMA) was initiated by the European Commission and is jointly organised by 39 European Universities; The Chairperson is elected annually by the Council of EMA Directors; For its pioneering role, EMA was awarded an Honourable Mention of the 2006 UNESCO Prize for Human Rights Education. since 1998 AUSTRIAN NATIONAL DIRECTOR REPRESENTING THE UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA IN THE EMA PROGRAMME EMA is based in the Monastery of San Nicolò, the Lido, Venice; Appointed by the Rector of the University of Vienna. -

A-HRC-13-42.Pdf

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/13/42 19 February 2010 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Thirteenth session Agenda item 3 PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF ALL HUMAN RIGHTS, CIVIL, POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS, INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO DEVELOPMENT JOINT STUDY ON GLOBAL PRACTICES IN RELATION TO SECRET DETENTION IN THE CONTEXT OF COUNTERING TERRORISM OF THE SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF HUMAN RIGHTS AND FUNDAMENTAL FREEDOMS WHILE COUNTERING TERRORISM, MARTIN SCHEININ; THE SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON TORTURE AND OTHER CRUEL, INHUMAN OR DEGRADING TREATMENT OR PUNISHMENT, MANFRED NOWAK; THE WORKING GROUP ON ARBITRARY DETENTION REPRESENTED BY ITS VICE-CHAIR, SHAHEEN SARDAR ALI; AND THE WORKING GROUP ON ENFORCED OR INVOLUNTARY DISAPPEARANCES REPRESENTED BY ITS CHAIR, JEREMY SARKIN* ** * Late submission. ** The annexes are reproduced in the language of submission only. GE.10-11040 A/HRC/13/42 page 2 Summary The present joint study on global practices in relation to secret detention in the context of countering terrorism was prepared, in the context of their respective mandates, by the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (represented by its Vice- Chair), and the Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances (represented by its Chair). Given that the violation of rights associated with secret detention fell within their respective mandates, and in order to avoid duplication of efforts and ensure their complementary nature, the four mandate holders decided to undertake the study jointly. -

Manfred Nowak

MANFRED NOWAK PROFESSOR OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND HUMAN RIGHTS, UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA CO-DIRECTOR, LUDWIG BOLTZMANN INSTITUTE OF HUMAN RIGHTS (BIM, VIENNA) SECRETARY GENERAL, EUROPEAN INTER-UNIVERSITY CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATISATION (EIUC, VENICE) INDEPENDENT EXPERT LEADING THE UNITED NATIONS GLOBAL STUDY ON CHILDREN DEPRIVED OF LIBERTY, OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (OHCHR, GENEVA) EDUCATION 1986 DR. HABIL OF CONSTITUTIONAL LAW (UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA) 1975 LL.M (COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY NEW YORK) 1973 DR. IURIS (UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA) OTHER FUNCTIONS since 2016 INDEPENDENT EXPERT LEADING THE UNITED NATIONS GLOBAL STUDY ON CHILDREN DEPRIVED OF LIBERTY, OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS (OHCHR), GENEVA since 2016 SECRETARY GENERAL OF THE EUROPEAN INTER-UNIVERSITY CENTRE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS AND DEMOCRATISATION (EIUC), VENICE since 2016 MEMBER OF THE ADVISORY BOARD OF THE EUROPEAN FORUM ALPBACH since 2014 HEAD OF THE INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH CENTRE HUMAN RIGHTS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA since 2012 VICE CHAIR OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD OF THE EU AGENCY FOR FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS (FRA) IN VIENNA since 2012 SCIENTIFIC DIRECTOR OF THE VIENNA MASTER OF ARTS IN HUMAN RIGHTS, UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA since 2012 MEMBER OF THE OMV (INTERNATIONAL OIL AND GAS COMPANY) ADVISORY BOARD FOR RESOURCEFULNESS since 2010 VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE AUSTRIAN UNESCO COMMISSION since 1995 MEMBER AND HONORARY MEMBER OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF JURISTS (ICJ), GENEVA since 1992 MEMBER OF THE BOARD OF THE