Neglected Tropical Diseases: Background, Responses, and Issues for Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TESTIMONY Peter J. Hotez MD, Phd President, Sabin Vaccine Institute

TESTIMONY Peter J. Hotez MD, PhD President, Sabin Vaccine Institute “The Growing Threat of Cholera and Other Diseases in the Middle East” Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Committee on Foreign Affairs United States House of Representatives March 2, 2016 Mr. Chairman and Members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to speak with you today. I am Peter Hotez, a biomedical scientist and pediatrician. I am the dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine and also the Texas Children’s Hospital Endowed Chair in Tropical Pediatrics based at the Texas Medical Center in Houston. I am also past president of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, and currently serve as President of the Sabin Vaccine Institute, a non-profit which develops vaccines for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) through a product development partnership (PDP) model. This year I am also serving as US Science Envoy for the State Department and White House Office of Science and Technology Policy focusing on the urgency to develop vaccines for diseases that are emerging in the Middle East and North Africa due to the breakdowns in health systems in the ISIS occupied conflict zones in Syria, Iraq, Libya, and also Yemen. In my submitted written testimony I highlighted some of the successes in US global health policy, many of which can be attributed to the hard work of this Subcommittee working hand in glove with two presidential administrations since 2000. I cite evidence from the Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) that brings together hundreds of scientists - I am also a part of this - who are measuring the impact of large scale global health programs. -

A Call to Support Francophone African

KNOWLEDGE BRIEF Health, Nutrition and Population Global Practice A CALL TO SUPPORT FRANCOPHONE Public Disclosure Authorized AFRICAN COUNTRIES TO END THE TREMENDOUS SUFFERING FROM NTDs Gaston Sorgho, Fernando Lavadenz and Opope Oyaka Tshivuila Matala December 2018 KEY MESSAGES: • Eighteen Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) and Malaria account together for 22% of the total burden of communicable diseases in 25 Francophone African Countries (FPACs). Public Disclosure Authorized • The cumulative impact of NTDs decreases the quality of life of households, slows economic growth and results in millions of dollars in lost economic productivity annually. For example, the World Bank (WB) estimates annual losses of US$33 million in Cameroon, US$13 million in Chad and US$9 million in Madagascar. • Of the 18 NTDs, 5 can be controlled by preventive chemotherapy (PC) through safe Mass Drug Administration (MDA). • In 2017, the WB launched the Deworming Africa Initiative (DAI), with the purpose of raising the profile of NTDs control and elimination efforts among endemic Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries to eliminate NTDs as a public health threat. • DAI’s strategy seeks to reduce the burden of NTDs in 3 key population groups that mostly impact on human capital: young children (12-23 months), pregnant women, and school-age children (SAC) (5-14 years of age). To achieve this objective in a sustainable way, DAI supports Country efforts to strengthen the coordinated engagement of the health, education, water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) and economic sectors with a national prevention and control strategy. • The WB's total annual investments in NTDs control have increased from US$3.3 million in 2013 to US$13.9 million in 2018. -

1999 Annual Report

1999 1999 BANBURY CENTER DIRECTOR'S REPORT The Banbury Center program continues to be as eclectic and exciting as ever. The year was filled with more meetings than ever before-a record 23 of them! Laboratory scientists used the Center for seven in-house meetings, and local community groups came here on eight occasions. Together with the five neurobiology courses, there was hardly a week when the Center was not in use. Not surprisingly, 1999 was also a record year for the number of visitors to Banbury Center: 667 par ticipants attended the 23 meetings. The demographics of our participants remain much the same: 25% of visitors to Banbury Center came from abroad, with the United Kingdom, Germany, and Canada lead ing the way. Of the American scientists, those from New York, Massachusetts, and California together accounted for more than 32% of the total. However, participants were drawn from no fewer than 42 states. This is the first year that we have been able to use the Meier House to accommodate participants, which proved to be wonderful. Now the number of participants that we can house on the Banbury estate matches the number we can have in the Conference Room-we do not have to transport peo ple between the Center and the main campus. Biological and biomedical research is becoming ever more interdisciplinary, and as it does so, it also becomes ever more difficult to categorize the topics of Banbury Center meetings. A meeting may deal with the same phenomenon in a range of organisms, or many different strategies may be used to study one phenomenon in a single species. -

Treating Rare and Neglected Pediatric Diseases: Promoting the Development of New Treatments and Cures

S. HRG. 111–1147 TREATING RARE AND NEGLECTED PEDIATRIC DISEASES: PROMOTING THE DEVELOPMENT OF NEW TREATMENTS AND CURES HEARING OF THE COMMITTEE ON HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON EXAMINING TREATING RARE AND NEGLECTED PEDIATRIC DISEASES, FOCUSING ON PROMOTING THE DEVELOPMENT OF NEW TREAT- MENTS AND CURES JULY 21, 2010 Printed for the use of the Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–592 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 COMMITTEE ON HEALTH, EDUCATION, LABOR, AND PENSIONS TOM HARKIN, Iowa, Chairman CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut MICHAEL B. ENZI, Wyoming BARBARA A. MIKULSKI, Maryland JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire JEFF BINGAMAN, New Mexico LAMAR ALEXANDER, Tennessee PATTY MURRAY, Washington RICHARD BURR, North Carolina JACK REED, Rhode Island JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia BERNARD SANDERS (I), Vermont JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona SHERROD BROWN, Ohio ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah ROBERT P. CASEY, JR., Pennsylvania LISA MURKOWSKI, Alaska KAY R. HAGAN, North Carolina TOM COBURN, M.D., Oklahoma JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon PAT ROBERTS, Kansas AL FRANKEN, Minnesota MICHAEL F. BENNET, Colorado DANIEL SMITH, Staff Director PAMELA SMITH, Deputy Staff Director FRANK MACCHIAROLA, Republican Staff Director and Chief Counsel (II) CONTENTS STATEMENTS WEDNESDAY, JULY 21, 2010 Page Harkin, Hon. Tom, Chairman, Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, opening statement .............................................................................. -

Hookworm (Ancylostomiasis)

Hookworm (ancylostomiasis) Hookworm (ancylostomiasis) rev Jan 2018 BASIC EPIDEMIOLOGY Infectious Agent Hookworm is a soil transmitted helminth. Human infections are caused by the nematode parasites Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale. Transmission Transmission primarily occurs via direct contact with fecal contaminated soil. Soil becomes contaminated with eggs shed in the feces of an individual infected with hookworm. The eggs must incubate in the soil for several days before they become infectious and are able to be transmitted to another person. Oral transmission can sometimes occur from consuming improperly washed food grown or exposed to fecal contaminated soil. Transmission can also occur (rarely) between a mother and her fetus/infant via infected placental or mammary tissue. Incubation Period Eggs must incubate in the soil for 5-10 days before they mature into infectious filariform larvae that can penetrate the skin. Within the first 10 days following penetration of the skin filariform larvae will migrate to the lungs and occasionally cause respiratory symptoms. Three to five weeks after skin penetration the larvae will migrate to the intestinal tract where they will mature into an adult worm. Adult worms may live in the intestine for 1-5 years depending on the species. Communicability Human to human transmission of hookworm does NOT occur because part of the worm’s life cycle must be completed in soil before becoming infectious. However, vertical transmission of dormant filariform larvae can occur between a mother and neonate via contaminated breast milk. These dormant filariform larvae can remain within in a host for months to years. Soil contamination is perpetuated by fecal contamination from infected individuals who can shed eggs in feces for several years after infection. -

(ITFDE) October 22, 2019

Summary of the Thirtieth Meeting of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication (ITFDE) October 22, 2019 The 30th Meeting of the International Task Force for Disease Eradication (ITFDE) was convened at The Carter Center in Atlanta, GA, USA from 8:30 am to 5:00 pm on October 22, 2019 to discuss the potential for eradication of measles and rubella. The Task Force members are Dr. Stephen Blount, The Carter Center (Chair); Dr. Peter Figueroa, The University of the West Indies, Jamaica; Dr. Donald Hopkins, The Carter Center; Dr. Fernando Lavadenz, The World Bank; Dr. Mwelecele Malecela, World Health Organization (WHO); Professor David Molyneux, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine; Dr. Ana Morice, Independent Consultant; Dr. Stefan Peterson, UNICEF; Dr. David Ross, The Task Force for Global Health; Dr. William Schluter, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); Dr. Nilanthi de Silva, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka/WHO Strategic and Technical Advisory Group for Neglected Tropical Diseases (STAG-NTDs); Dr. Dean Sienko, The Carter Center; Dr. Laurence Slutsker, PATH; Dr. Jordan Tappero, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Dr. Ricardo Thompson, National Institute of Health (Mozambique); and Dr. Dyann Wirth, Harvard School of Public Health. Eleven Task Force members (Blount, Figueroa, Hopkins, Morice, Ross, Sienko, de Silva, Slutsker, Tappero, Thompson, Wirth) participated in this meeting; three were represented by an alternate (Drs. Fatima Barry for Lavadenz, Steve Cochi for Schluter, Yodit Sahlemariam for Peterson). Presenters included Drs. Sunil Bahl, WHO/SEARO; Amanda Cohn, CDC; Matthew Hanson, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Alan Hinman, The Task Force for Global Health; Mark Jit, London School of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene; Ann Lindstrand, WHO/Geneva; Balcha Masresha, WHO/AFRO; Patrick O’Connor, WHO/Europe; and Desiree Pastor, Pan American Health Organization (WHO/PAHO). -

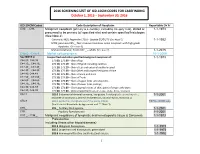

2016 SCREENING LIST of ICD-10CM CODES for CASEFINDING October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016

2016 SCREENING LIST OF ICD-10CM CODES FOR CASEFINDING October 1, 2015 – September 30, 2016 ICD-10-CM Codes Code Description of Neoplasm Reportable Dx Yr C00._- C96._ Malignant neoplasm (primary & secondary; excluding category C44), stated or 1-1-1973 presumed to be primary (of specified site) and certain specified histologies (See Note 2) Carcinoid, NOS; Appendix C18.0 - Update 01/01/15 (See Note 5) 1-1-1992 MCN; pancreas C25._; Non-invasive mucinous cystic neoplasm with high grade dysplasia. (See note 6) Mature teratoma; Testis C62._ – adults (See note 7) 1-1-2015 C4a.0_-C4a.9_ Merkel cell carcinoma 10-1-2009 See NOTE 4 Unspecified and other specified malignant neoplasm of : 1-1-1973 C44.00.-C44.09 173.00, 173.09 – Skin of Lip C44.10_, C44.19_ 173.10, 173.19 – Skin of Eyelid including canthus C44.20_, C44.29_ 173. 20, 173.29 – Skin of Ear and external auditory canal C44.30_, C44.39_ 173.30, 173.39 – Skin Other and unspecified parts of face C44.40, C44.49 173. 40, 173.49 – Skin of Scalp and neck C44.50_, C44.59_ 173.50, 173.59 – Skin of Trunk C44.60_, C44.69_ 173. 60, 173.69 – Skin of Upper limb and shoulder, C44.70_, C44.79_ 173.70, 173.79 – Skin of Lower limb and hip; C44.80, C44.89 173.80, 173.89 – Overlapping lesions of skin, point of origin unknown; C44.90, C44.99 173.90, 173.99 - Sites unspecified (excludes Labia, Vulva, Penis, Scrotum) C54.1 182.0 Endometrial stromal sarcoma, low grade; Endolymphatic stromal myosis ; 1-1-2001 Endometrial stromatosis, Stromal endometriosis, Stromal myosis, NOS (C54.1) C56.9 183.0 Borderline malignancies -

Lecture 5: Emerging Parasitic Helminths Part 2: Tissue Nematodes

Readings-Nematodes • Ch. 11 (pp. 290, 291-93, 295 [box 11.1], 304 [box 11.2]) • Lecture 5: Emerging Parasitic Ch.14 (p. 375, 367 [table 14.1]) Helminths part 2: Tissue Nematodes Matt Tucker, M.S., MSPH [email protected] HSC4933 Emerging Infectious Diseases HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2 Monsters Inside Me Learning Objectives • Toxocariasis, larva migrans (Toxocara canis, dog hookworm): • Understand how visceral larval migrans, cutaneous larval migrans, and ocular larval migrans can occur Background: • Know basic attributes of tissue nematodes and be able to distinguish http://animal.discovery.com/invertebrates/monsters-inside- these nematodes from each other and also from other types of me/toxocariasis-toxocara-roundworm/ nematodes • Understand life cycles of tissue nematodes, noting similarities and Videos: http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside- significant difference me-toxocariasis.html • Know infective stages, various hosts involved in a particular cycle • Be familiar with diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, pathogenicity, http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me- &treatment toxocara-parasite.html • Identify locations in world where certain parasites exist • Note drugs (always available) that are used to treat parasites • Describe factors of tissue nematodes that can make them emerging infectious diseases • Be familiar with Dracunculiasis and status of eradication HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 3 HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 4 Lecture 5: On the Menu Problems with other hookworms • Cutaneous larva migrans or Visceral Tissue Nematodes larva migrans • Hookworms of other animals • Cutaneous Larva Migrans frequently fail to penetrate the human dermis (and beyond). • Visceral Larva Migrans – Ancylostoma braziliense (most common- in Gulf Coast and tropics), • Gnathostoma spp. Ancylostoma caninum, Ancylostoma “creeping eruption” ceylanicum, • Trichinella spiralis • They migrate through the epidermis leaving typical tracks • Dracunculus medinensis • Eosinophilic enteritis-emerging problem in Australia HSC4933. -

Private Equity Guide to Life Sciences Investing Under the Trump Administration: Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Developments

Debevoise In Depth Private Equity Guide to Life Sciences Investing Under the Trump Administration: Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Developments March 15, 2018 Overview As the Trump administration enters its second year, it is an ideal time for private equity funds and investors active in the life sciences arena to reflect on the impact of the new administration—and a new commissioner—on the Food and Drug Administration (“FDA”). Of all the potential Trump nominees to head the agency, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, a physician, was clearly the most mainstream choice. Commissioner Gottlieb previously served as FDA’s Deputy Commissioner for Medical and Scientific Affairs and, before that, as a senior advisor to the FDA Commissioner. As a cancer survivor, he also had first-hand experience as a patient— perhaps informing some of the regulatory strategies he has pursued. Those strategies have been significant. While many other federal regulatory agencies have been marginalized or victims of regulatory paralysis, FDA, under Scott Gottlieb’s leadership, has forged ahead with sweeping initiatives intended to accelerate drug and device approvals and clearances, embrace innovation and new technologies, lower regulatory burdens, and enhance therapeutic opportunities.1 This fast-moving regulatory landscape, combined with robust innovation in the life sciences sector, creates both opportunities and challenges for private equity sponsors. In recent years, private equity sponsors have continued to prioritize investments in both the healthcare and life sciences industries and 1 When Gottlieb took the reins at FDA, the agency was already focused on a number of ongoing initiatives such as the implementation of the 21st Century Cures Act, enacted at the end of 2016, and the passage of the FDA Reauthorization Act of 2017 (“FDARA”). -

Equine Recommended Deworming Schedule

EQUINE FIELD SERVICE EQUINE RECOMMENDED DEWORMING SCHEDULE ADULT HORSE SCHEDULE n LOW SHEDDERS (<200 EPG – eggs per gram of manure) Fecal Egg Count performed prior to deworming in spring (ideally spring and fall) SPRING (March) – ivermectin (Equell®, Zimectrin®, Rotectin®, IverCare®), moxidectin (Quest®) FALL (October) – ivermectin w/praziquantel (Equimax®, Zimectrin Gold®) or moxidectin with praziquantel (Quest Plus®) n MODERATE SHEDDERS (200 – 500 EPG) Fecal Egg Count performed prior to deworming in spring (ideally spring and fall) SPRING (March) – Ivermectin (Equell®, Zimectrin®, Rotectin®, IverCare, etc), moxidectin (Quest®) or double-dose fenbendazole for 5 days (Panacur® PowerPak) LATE SUMMER (July) – pyrantel pamoate (Strongid paste®, TapeCare Plus®, etc), fenbendazole (Panacur®, Safe-Guard®) EARLY WINTER (November) – ivermectin w/praziquantel (Equimax®, Zimectrin Gold®) or moxidectin with praziquantel (Quest Plus®) n HIGH SHEDDERS (>500 EPG) Fecal Egg Count performed prior to deworming in spring and fall to monitor for signs of resistance SPRING (March) – ivermectin (Equell®, Zimectrin®, Rotectin®, IverCare®), moxidectin (Quest®) or double-dose of fenbendazole for 5 days (Panacur® PowerPak) SUMMER (June) – pyrantel pamoate (Strongid paste®, TapeCare Plus®), fenbendazole (Panacur, SafeGuard®) or Oxibendazole (Anthelcide®) FALL (September) – ivermectin w/ praziquantel (Equimax®, Zimectrin Gold®) or moxidectin with praziquantel (Quest Plus®) WINTER (December) – pyrantel pamoate (Strongid paste®, TapeCare Plus®), fenbendazole (Panacur®, -

Studies Show That Fecal Dx Antigen Tests Allow for Earlier Detection of More Intestinal Parasites

Research update Studies show that Fecal Dx antigen tests allow for earlier detection of more intestinal parasites Antigen detection is commonly used today to diagnose Results heartworm and Giardia infections, and now it is available for In the 1,156 field fecal samples for the roundworm and hookworm additional parasites. IDEXX Reference Laboratories, as a leader study and the 1,000 field fecal samples for the whipworm study, in pet healthcare innovation, has developed immunoassays for egg-positive roundworm, hookworm, and whipworm results were the detection of hookworm, roundworm, and whipworm antigens noted in 23, 13, and 27 samples, respectively. In contrast, 26, 19, in feces of dogs and cats. These antigens are secreted from the and 35 samples were antigen positive for roundworm, hookworm, adult worm and are not present in their eggs, which allows for and whipworm. The T. canis ELISA detected T. cati coproantigen in detection of prepatent stages as well as the ability to overcome the feline samples. Fecal antigens detected more infections than did challenges of intermittent egg laying. Earlier detection during the fecal flotation. prepatent period will also reduce the frequency of environmental contamination with potentially infectious eggs. Roundworm Hookworm Whipworm Two recent papers describing the performance of the Fecal Dx™ antigen tests, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) Fecal flotation 23 13 27 developed by IDEXX for coproantigen detection of Trichuris vulpis, positive Ancylostoma caninum and Toxocara canis in dogs and Toxocara cati in cats, are summarized below. Fecal Dx antigen 26 19 35 • Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for coproantigen detection test positive of Trichuris vulpis in dogs1 • Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for coproantigen Table 1. -

General Horse Care MP501

MP501 General Horse Care DIVISION OF AGRICULTURE RESEARCH & EXTENSION University of Arkansas System University of Arkansas, United States Department of Agriculture, and County Governments Cooperating General Horse Care General Nutrition and Feeding Management ...............................................................................1 Determining the Amount to Feed ......................................................................................2 Selecting Grain and Hay ....................................................................................................3 Vaccinations ..................................................................................................................................5 Deworming ...................................................................................................................................6 Parasite Control via Manure Management .......................................................................7 Resisting Resistance .........................................................................................................7 Deworming Schedules ......................................................................................................7 Recognizing the Signs of Equine Colic ........................................................................................8 Preventing Barn Fires ...................................................................................................................9 Overview Mark Russell Instructor - Animal Science University