Terry Lander Draft Predesign Study.” October 6, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Program

OFFICIAL PROGRAM OFFICIAL WATCH Long run for WASHINGTON-OHIO STATE FOR THIS GAME CONTENTS The University Presidents ....................................... ·· · ···· ··· · .. 2 * **** ** your money University of Washington Representatives ........................ .. 3 University of Washington ..................................................... 4 LONGINES University of Washington Campus ....................................... 5 THE WORLD'S 6 MOST HONORED \I The College of Veterinary Medicine .................................... .. WATCH ,.._ Ohio State University Football Coaching Staff ...................... 7 ===:---- ,---.,,, I Ohio State Football Player Pages ..................9, 18, 20, 32, 34, 40 •. : - Ohio Stadium Information .................................................... 11 .• • .... •• •• University of Washington Football Player Pages ...... 12, 30, 36, 46 Ohio State University Athletic Staff ....................................... 16 • ••... I University of Washington Football Coaching Staff .............. .. 19 Ohio State University Football Roster .............. ..... ..... .. .. .... .. .. 22 University of Washington Football Roster .............................. 27 Ohio State Football Team Picture ................................ ... .... 28 Half-Time Music by the Marching Band .................................. 43 - Wilbur E. Snypp, Editor and Advertising Manager John F. Hummel, Circulation Manager National Advertising Representative: Spencer Advertising Co., 271 Madison Ave., New York, N.Y. lon,lnes S·Star Admiral -

Rainier Square Development DRAFT

Rainier Square Development University of Washington Metropolitan Tract Addendum to Final Environmental Impact Statement Downtown Height and Density Changes January 2005 Master Use Permit Project No. 3017644 City of Seattle Department of Planning and Development February 11, 2015 DRAFT FOR CITY STAFF REVIEW 0NLY Prepared by: Parametrix Inc. Environmental Impact Statement Addendum Addendum to ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT for the Downtown Height and Density Changes January 2005 Addressing Environmental Impacts of Rainier Square Development University of Washington Metropolitan Tract Rainier Square Redevelopment Master Use Permit # 3017644 City of Seattle Department of Planning and Development This Environmental Impact Statement Addendum has been prepared in compliance with the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) of 1971 (Chapter 43.21C, Revised Code of Washington); the SEPA Rules, effective April 4, 1984, as amended (Chapter 197-11 Washington Administrative Code); and rules adopted by the City of Seattle implementing SEPA – Seattle’s Environmental Policies and Procedures Code (Chapter 25.05, Seattle Municipal Code). The Seattle Department of Planning and Development (DPD). DPD has determined that this document has been prepared in a responsible manner using appropriate methodology and DPD has directed the areas of research and analysis that were undertaken in preparation of this DSEIS. This document is not an authorization for an action, nor does it constitute a decision or a recommendation for an action. Date of Issuance of this EIS Addendum .............................................DATE Rainier Square Development i University of Washington Metropolitan Tract Environmental Impact Statement Addendum Cite as: City of Seattle Department of Planning and Development University of Washington Metropolitan Tract Rainier Square Redevelopment February 2015 Addendum to Final Environmental Impact Statement Downtown Height and Density Proposal, January 2005 Prepared by Parametrix Inc., Seattle, WA. -

Library Directions/ a Newsletter of the University of Washington Libraries

Library Directions/ A Newsletter of the University of Washington Libraries Volume 11 No. 3 Spring 2001 Earthquake! books on the fl oor. In most of the library, however, Gordon Aamot, Acting Associate Director of Libraries stack ranges didn’t collapse to the fl oor but, instead, sagged lengthwise—changing the shape of the range The Nisqually Earthquake that shook the Puget from a rectangle to a parallelogram. Considering the Sound region the morning of February 28, 2001, did damage, it’s striking how few books actually fell off not disrupt any of the Libraries electronic services, the shelves. The University was initially very con- but it knocked tens of thousands of books off the cerned about the possibility of the stacks collapsing shelves, damaged stack ranges, and impacted service and crashing through windows, so the library was order- in a number of University Libraries units. Over 1000 ed closed until the windows could be covered with volumes were damaged during the quake. We consider plywood. On March 1, the fi rst fl oor of the Engineering ourselves extremely fortunate that no one was seriously Library opened again but offered only limited services. injured and that the Libraries did not suffer greater Due to safety concerns, the second, third, and fourth physical damage to its facilities and collections. fl oors were closed to the public after the earthquake. One of the best pieces of advice we received after the By the beginning of Spring Quarter, Libraries, Univer- quake was to document damage as fully as possible. sity, and Sellen Construction staff developed a way to Staff members captured hundreds of images, many of stabilize the shelving so that staff could retrieve upper which can be seen at www.lib.washington.edu/about/ floor materials for users. -

Library Directions: Volume 13, No

Library Directions: Volume 13, No. 2 a newsletter of the Spring 2003 University of Washington Libraries Library Directions is produced two times a year Letter from the Director by UW Libraries staff. Inquiries concerning content should be sent to: Library Directions All books are rare books. —Ivan Doig (2002) University of Washington Libraries Box 352900 In Ivan Doig’s compelling essay in this issue of Library Directions, he Seattle, WA 98195-2900 (206) 543-1760 reminds us that “all books are rare books.” We run the risk of losing ([email protected]) the lore, the curiosity, and uniqueness of each author’s insights if we Paul Constantine, Managing Editor Susan Kemp, Editor, Photographer don’t adequately preserve and make accessible the range of human Diana Johnson, Mark Kelly, Stephanie Lamson, eff ort through our libraries. Just as all books are rare books, all digital Mary Mathiason, Mary Whiting, Copy Editors publications are potentially rare publications. We run the same risk of Library Directions is available online at www.lib.washington.edu/about/libdirections/current/. seeing digital scholarship evaporate if we don’t archive and preserve Several sources are used for mailing labels. Please pass the new and evolving forms of publication. multiple copies on to others or return the labels of the unwanted copies to Library Directions. Addresses containing UW campus box numbers were obtained from the HEPPS database and corrections should On March 9-11, the University Libraries hosted a retreat on digital scholarship. Made possible be sent to your departmental payroll coordinator. through the generous funding of the Andrew W. -

Complete Career Resume

COMPLETE CAREER RESUME CONTACT INFORMATION: Roger Shimomura 1424 Wagon Wheel Road Lawrence, Kansas 66049-3544 Tele: 785-842-8166 Cell: 785-979-8258 Email: [email protected] Web: www.rshim.com EDUCATION: Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York, M.F.A., Painting, 1969 University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, B.A., Commercial Design, 1961 Also attended: Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, Painting, (Summer), 1968 Stanford University, Palo Alto, California, Painting, (Summer), 1967 Cornish School of Allied Arts, Seattle, Washington, Illustration, (Fall), 1964 HONORS AND AWARDS: Personal papers being collected by the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Hall of Fame, Garfield Golden Graduate, Garfield High School, Seattle, Washington, June, 2013 Artist-in-Residence, New York University, Asian Pacific American Institute, New York City, New York, September 2012-May, 2013 Commencement address, Garfield High School, Seattle, Washington, June, 2012 150th Anniversary Timeless Award, University of Washington College of Arts & Sciences , Seattle, Washington, May, 2012 Designated U.S.A.Fellow in Visual Arts, Ford Foundation, Los Angeles, California, December, 2011 Honoree: "Exceptional Person in Food, Fashion and the Arts", Asian American Arts Alliance, New York City, New York, October, 2008 Community Voice Award, "Unsung Heros of the Community", International Examiner, Seattle, Washington, May, 2008 First Kansas Master Artist Award in the Visual Arts, Kansas Arts Commission, Topeka, Kansas, January, 2008 Distinguished -

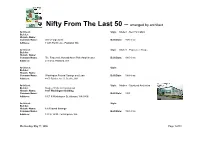

Nifty from the Last 50 – Arranged by Architect

Nifty From The Last 50 – arranged by architect Architect: Style: Modern - New Formalism Builder: Historic Name: Common Name: Wells Fargo Bank Built Date: 1970 circa Address: 11205 Pacific Ave, Parkland, WA Architect: Style: Modern - Populuxe / Googie Builder: Historic Name: Common Name: The Fingernail, Howard Amon Park Amphitheater Built Date: 1960 circa Address: Lee Blvd, Richland, WA Architect: Style: Builder: Historic Name: Common Name: Washington Federal Savings and Loan Built Date: 1968 circa Address: 4800 Rainier Ave S, Seattle, WA Architect: Style: Modern - Structural Aesthetics Builder: Dawley Brothers Construction Historic Name: 1007 Washington Building Common Name: Built Date: 1959 Address: 1007 N Washington St, Olympia, WA 98501 Architect: Style: Builder: Historic Name: 1st Federal Savings Common Name: Built Date: 1968 circa Address: 141 W 1st St, Port Angeles, WA Wednesday, May 17, 2006 Page 1 of 51 Architect: Style: Builder: Historic Name: 200 Aloha St. Apartments Common Name: Built Date: 1953 Address: 200 Aloha St, Seattle, WA Architect: Style: Modern - International Style Builder: Historic Name: 210 Union Building Common Name: Built Date: 1954 Address: 210 Union Ave SE, Olympia, WA 98501 Architect: Style: Builder: Historic Name: Alaska Copper and Brass Company Common Name: Built Date: 1957 circa Address: 3223 6th Ave S, Seattle, WA Architect: Style: Builder: Historic Name: Auburn High School Common Name: Built Date: 1950 Address: 800 4th St NE, Auburn, WA 98002 Architect: Style: Builder: Historic Name: Bank Common Name: -

LDTC Typedescription LDLI Category Library Branch

LDTC_TypeDescription LDLI_Category Library Branch SecondaryName LDLI_Address1 LDLI_Address2 LDLI_Address3 LDLI_Address4 LDLI_City LDLI_State LDLI_Zip LDLI_County LDLI_AddPhones LDLI_FAX LDLI_email LDLI_URL Academic Libraries 2-year Bates Technical College Bates Technical College Library Downtown Campus Bates Technical College, 1101 S Yakima Ave, Tacoma Tacoma WA 98405-4895 Pierce (253) 680-7220 2536807221 [email protected] http://www.batestech.edu/Library Academic Libraries 2-year Bates Technical College Bates Technical College Library South Campus Bates Technical College 2201 S 78th St, Room E201 Tacoma WA 98409-9000 Pierce (253) 680-7550 2536807551 [email protected] http://www.batestech.edu/library Academic Libraries 2-year Bellevue College Bellevue College 3000 Landerholm Circle SE D260 Bellevue WA 98007-6484 King 425-564-2255 4255646186 [email protected] https://bellevuecollege.edu/lmc Academic Libraries 2-year Bellingham Technical College Bellingham Technical College Library 3028 Lindbergh Ave Bellingham WA 98225-1599 Whatcom (360) 752-8383 3607528384 [email protected] https://www.btc.edu/Library Academic Libraries 2-year Big Bend Community College Big Bend Community College William C. Bonaudi Library 7662 Chanute St., Building 1800 Moses Lake WA 98837 Grant (509) 793-2350 [email protected] http://libguides.bigbend.edu/home Academic Libraries 2-year Clark College Cannell Library Clark College Libraries 1933 Fort Vancouver Way Vancouver WA 98663 Clark 360-992-2151 3609922869 http://library.clark.edu Academic -

In Joint Session With

September 8, 2011 TO: Members of the Board of Regents Ex officio Representatives to the Board of Regents FROM: Joan Goldblatt, Secretary of the Board of Regents RE: Schedule of Meetings: September 15, 2011 Special Meeting WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 14, 2011 5:30 p.m. Hill-Crest DINNER FOR REGENTS AND GUESTS THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 15, 2011 8:30 to 10:15 a.m. 142 Gerberding Hall FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Smith (Chair), Blake, Brotman, Cole (alternate), Jewell 10:30 to 11:20 a.m. 142 Gerberding Hall ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles in Joint Session with FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Smith (Chair), Blake, Brotman, Cole (alternate), Jewell 11:35 a.m. to 12:10 p.m. 142 Gerberding Hall ACADEMIC AND STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Harrell (Chair), Barer, Cole, Gates, Knowles 12:30 p.m. PHOTOGRAPH OF THE BOARD OF REGENTS 1:00 p.m. Petersen Room SPECIAL MEETING OF THE BOARD OF Allen Library REGENTS The Regular Meeting of the Board for Thursday, September 15, 2011 is cancelled due to the change in scheduling of the meeting of the full Board from 3:00 p.m. to 1:00 p.m. The Board with the revised schedule will convene a Special Meeting on Thursday, September 15, 2011 with committee meetings beginning at 8:30 a.m. and the full session of the Board scheduled at 1:00 p.m. To request disability accommodation, contact the Disability Services Office at: 206.543.6450 (voice), 206.543.6452 (TTY), 206.685.7264 (fax), or email at [email protected]. -

1411 4Th Ave Seattle, WA 98101 Igniting Innovation and Imagination in the Heart of Seattle’S CBD

1411 4th Ave Seattle, WA 98101 Igniting Innovation and Imagination in the Heart of Seattle’s CBD Our historical location at 1411 4th Ave spans eleven floors of flexible office space in the heart of downtown Seattle. Close proximity to bus lines, the University Street Station light rail, and Pier 50 ferry terminal make getting here, and anywhere else in the city, easy. Some of Seattle’s best restaurants, cafés, bars, and attractions are within walking distance of the office, making your work day that much better. Whether you’re juicy burger or juice bar, happy hour or 5-star cuisine, in need of a single desk or an entire suite, you’ll find a progressive, welcoming community here that supports who you are and where you’re going. Examples of WeWork spaces 1411 4th Ave | 2 1411 4th Ave | 3 Where Historic Beauty Meets Modern Workspace The arresting art deco façade of this historic 1929 landmark building gives way to light-filled, modern workspace that welcomes members from across industries. Comprised of unique visual elements and curated art, our workplace is designed to capture the innovative, industrious spirit that is ingrained in the building. Amenities include a meditation room, a new mothers’/wellness room, unlimited micro-roasted coffee, and premium conference rooms and lounges that cultivate a collaborative, supportive community. Bike storage and showers onsite make bike commutes and midday workouts easier. And our dog-friendly policy means your four-legged muse can come to work every day. Whether you’re flying solo and need a single desk or have a large team and need a suite, you’ll find space here that motivates you to push harder and inspires you to go further. -

Downtown Seattle

Commercial Revalue 2015 Assessment Roll AREA 30 King County, Department of Assessments Seattle, Wa. Lloyd Hara, Assessor Department of Assessments Accounting Division Lloyd Hara 500 Fourth Avenue, ADM-AS-0740 Seattle, WA 98104-2384 Assessor (206) 205-0444 FAX (206) 296-0106 Email: [email protected] http://www.kingcounty.gov/assessor/ Dear Property Owners: Property assessments for the 2015 assessment year are being completed by my staff throughout the year and change of value notices are being mailed as neighborhoods are completed. We value property at fee simple, reflecting property at its highest and best use and following the requirement of RCW 84.40.030 to appraise property at true and fair value. We have worked hard to implement your suggestions to place more information in an e-Environment to meet your needs for timely and accurate information. The following report summarizes the results of the 2015 assessment for this area. (See map within report). It is meant to provide you with helpful background information about the process used and basis for property assessments in your area. Fair and uniform assessments set the foundation for effective government and I am pleased that we are able to make continuous and ongoing improvements to serve you. Please feel welcome to call my staff if you have questions about the property assessment process and how it relates to your property. Sincerely, Lloyd Hara Assessor Area 30 Map The information included on this map has been compiled by King County staff from a variety of sources and is subject to change without notice. -

In Joint Session With

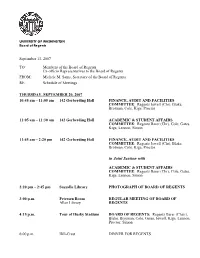

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON Board of Regents September 13, 2007 TO: Members of the Board of Regents Ex-officio Representatives to the Board of Regents FROM: Michele M. Sams, Secretary of the Board of Regents RE: Schedule of Meetings THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, 2007 10:45 am – 11:05 am 142 Gerberding Hall FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Jewell (Chr), Blake, Brotman, Cole, Kiga, Proctor 11:05 am – 11:30 am 142 Gerberding Hall ACADEMIC & STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Barer (Chr), Cole, Gates, Kiga, Lennon, Simon 11:45 am – 2:20 pm 142 Gerberding Hall FINANCE, AUDIT AND FACILITIES COMMITTEE: Regents Jewell (Chr), Blake, Brotman, Cole, Kiga, Proctor in Joint Session with ACADEMIC & STUDENT AFFAIRS COMMITTEE: Regents Barer (Chr), Cole, Gates, Kiga, Lennon, Simon 2:20 pm – 2:45 pm Suzzallo Library PHOTOGRAPH OF BOARD OF REGENTS 3:00 p.m. Petersen Room REGULAR MEETING OF BOARD OF Allen Library REGENTS 4:15 p.m. Tour of Husky Stadium BOARD OF REGENTS: Regents Barer (Chair), Blake, Brotman, Cole, Gates, Jewell, Kiga, Lennon, Proctor, Simon 6:00 p.m. Hill-Crest DINNER FOR REGENTS 1-1/209 9/20/07 UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON BOARD OF REGENTS Members of the Academic and Student Affairs Committee Regents Barer (Chair), Cole, Gates, Kiga, Lennon, Simon September 20, 2007 11:05 am – 11:30 am, 142 Gerberding Hall 1. Academic and Administrative Appointments ACTION A–1 Phyllis M. Wise, Provost and Executive Vice President 2. Establishment of the Master of Science and Doctor of Philosophy ACTION A–2 in the Department of Earth and Space Sciences Robert Winglee, Professor and Chair, Department of Earth and Space Sciences Suzanne T. -

1 13 14 12 11 Points of Interest 15

5 6 4 3 1 2 7 8 9 10 13 12 0 ¼ mile 11 0 500 1,000 feet uw.edu/maps LEGEND 14 Museums & galleries Information Points of interest Gatehouse Lecture & performance Light rail Husky merchandise Bus stop Ticket office Parking gate 15 Campus dining UW Police Cafés & markets Hospital POINTS OF INTEREST Information and Visitor Center 3 The Liberal Arts Quadrangle (the Quad) 6 University Book Store 9 Drumheller Fountain 12 UW Medical Center 15 UW Botanic Gardens The Visitor Center is next to the George Washington The Quad is the primary gathering place on campus, Located on the Ave, University Book Store is a The centerpiece of Rainier Vista, Drumheller Foun- One of the highest-ranked medical centers in Across the Montlake Bridge are the UW Botanic statue on the ground floor of the Odegaard especially when the Yoshino cherry trees bloom thriving independent bookstore that regularly hosts tain was built to highlight our spectacular view of America, UW Medical Center is also home to the Gardens and Washington Park Arboretum, one of Undergraduate Library. each spring. author events, signings and book clubs, in addition Mount Rainier. top-ranked UW School of Medicine. the oldest arboretums west of the Mississippi. to being the UW source for textbooks, art supplies, 1 Odegaard Undergraduate Library 4 Denny Hall technology and Husky gear. 10 Sylvan Grove and Columns 13 Husky Stadium The University of Washington is committed to In addition to offering research and writing services, Built in 1895, Denny Hall is the oldest building on At the south end of this picturesque shady grove With views of Lake Washington and the Cascade providing access, equal opportunity and reasonable Odegaard is home to By George Café.