February 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

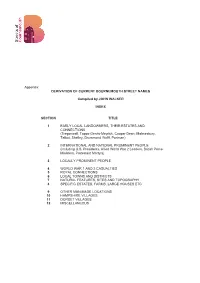

Appendix DERIVATION of CURRENT BOURNEMOUTH STREET NAMES

Appendix DERIVATION OF CURRENT BOURNEMOUTH STREET NAMES Compiled by JOHN WALKER INDEX SECTION TITLE 1 EARLY LOCAL LANDOWNERS, THEIR ESTATES AND CONNECTIONS (Tregonwell, Tapps -Gervis-Meyrick, Cooper Dean, Malmesbury, Talbot, Shelley, Drummond Wolff, Portman) 2 INTERNATIONAL AND NATIONAL PROMINENT PEOPLE (including U.S. Presidents, Allied World War 2 Leaders, British Prime Ministers, Protestant Martyrs) 3 LOCALLY PROMINENT PEOPLE 4 WORLD WAR 1 AND 2 CASUALTIES 5 ROYAL CONNECTIONS 6 LOCAL TOWNS AND DISTRICTS 7 NATURAL FEATURES, SITES AND TOPOGRAPHY 8 SPECIFIC ESTATES, FARMS, LARGE HOUSES ETC 9 OTHER MAN -MADE LOCATIONS 10 HAMPSHIRE VILLAGES 11 DORSET VILLAGES 12 MISCELLANEOUS 1 EARLY LOCAL LANDOWNERS, THEIR ESTATES AND CONNECTIONS A LEWIS TREGONWELL (FOUNDER OF BOURNEMOUTH) Berkeley Road. Cranborne Road. Exeter and Exeter Park Roads, Exeter Crescent and Lane. Grantley Road. Priory Road. Tregonwell Road. B TAPPS-GERVIS-MEYRICK FAMILY (LORD OF THE MANOR) Ashbourne Road. Bodorgan Road. Gervis Road and Place. Hannington Road and Place. Harland Road. Hinton and Upper Hinton Roads. Knyveton Road. Manor Road. Meyrick Road and Park Crescent. Wolverton Road. Wootton Gardens and Mount. C COOPER-DEAN FAMILY 1 General acknowledgment Cooper Dean Drive. Dean Park Road and Crescent. 2 Cooper-Dean admiration for the aristocracy and peerage Cavendish Road and Place. Grosvenor Road. Lonsdale Road. Marlborough Road. Methuen Road and Close. Milner Road. Portarlington Road and Close. Portchester Road and Place. 3 Biblical Names chosen by Cooper-Dean Ophir Road and Gardens. St Luke’s Road. St Paul’s Road. 4 Named after the family’s beloved Hampshire countryside (mainly on the Iford Estate) Cheriton Avenue. Colemore Road. -

The Frome 8, Piddle Catchmentmanagement Plan 88 Consultation Report

N 6 L A “ S o u t h THE FROME 8, PIDDLE CATCHMENTMANAGEMENT PLAN 88 CONSULTATION REPORT rsfe ENVIRONMENT AGENCY NATIONAL LIBRARY & INFORMATION SERVICE ANGLIAN REGION Kingfisher House. Goldhay Way. Orton Goldhay, Peterborough PE2 5ZR NRA National Rivers Authority South Western Region M arch 1995 NRA Copyright Waiver This report is intended to be used widely and may be quoted, copied or reproduced in any way, provided that the extracts are not quoted out of context and that due acknowledgement is given to the National Rivers Authority. Published March 1995 ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Hill IIII llll 038007 FROME & PIDDLE CATCHMENT MANAGEMENT PLAN CONSULTATION REPORT YOUR VIEWS The Frome & Piddle is the second Catchment Management Plan (CMP) produced by the South Wessex Area of the National Rivers Authority (NRA). CMPs will be produced for all catchments in England and Wales by 1998. Public consultation is an important part of preparing the CMP, and allows people who live in or use the catchment to have a say in the development of NRA plans and work programmes. This Consultation Report is our initial view of the issues facing the catchment. We would welcome your ideas on the future management of this catchment: • Hdve we identified all the issues ? • Have we identified all the options for solutions ? • Have you any comments on the issues and options listed ? • Do you have any other information or ideas which you would like to bring to our attention? This document includes relevant information about the catchment and lists the issues we have identified and which need to be addressed. -

Groundwater Levels the Majority of Groundwater Sites in Wessex Are ‘Normal’ Or ‘Above Normal’ for the Time of Year

Monthly water situation report Wessex Area Summary – February 2016 February rainfall was 136% of the long term average (LTA) but was distributed mainly in the first 8 days and then around mid month with the last half of the month being dry. The last 3 months have all had above average rainfall resulting in the 3 month total being 132% LTA. Rivers responded to the rainfall then were predominantly in recession from mid month. Soils remain wet close to capacity. Most groundwater sites have had significant recharge and are all normal or above for the time of year. Reservoir storage is almost at its maximum; Bristol water is at 99% of the total reservoir storage and Wessex Water is at capacity. Rainfall The start of the month was wet, 63% of Februarys rainfall fell within the first eight days. The rest of the month was mostly dry apart from a couple of wet days around the 17th. The average rainfall total across the Wessex Area was 136% of LTA (88 mm). Rainfall map and graph Soil Moisture Deficit The soil is wet, as expected for the time of year. The average soil moisture deficit across Wessex on 1 March 2016 was 1.08 mm, well below the LTA of 2.96 mm. SMD graph and maps River Flows River flows across the Wessex area were ‘exceptionally high’ around 6 February and the 18 February in response to the precipitation received at the start and middle of the month. Many of the stations in the north and along the southern edge of Wessex are ‘above normal’ or experiencing flows above the LTA. -

Key to Advert Symbols

This property list shows you all of the available vacancies across all the local authority partner areas within Dorset Home Choice. You will only be able to bid on properties that you are eligible for. For advice and assistance please contact your managing local authority partner Borough of Poole - 01202 633805 Bournemouth Borough Council - 01202 451467 Christchurch Borough Council - 01202 795213 East Dorset District Council - 01202 795213 North Dorset District Council - 01258 454111 Purbeck District Council - 01929 557370 West Dorset District Council - 01305 251010 Weymouth & Portland Borough Council - 01305 838000 Ways to bid (refer to the Scheme User Guide for more details) By internet at www.dorsethomechoice.org KEY TO ADVERT SYMBOLS Available for Available for transferring Available for homeseekers homeseekers only tenants only and transferring tenants Number of bedrooms in the property Minimum and maximum number of Suitable for families people who can live in the property Floor level of property, Pets may be allowed with the No pets if flat or maisonette permission of the landlord allowed Garden Shared Lift No Lift Fixed Tenancy showing SHARED Garden number of years Property designed for people of this age or above Mobility Level 1 - Suitable for wheelchair users for full-time indoor and outdoor mobility Mobility Level 2 - Suitable for people who cannot manage steps, stairs or steep gradients and require a wheelchair for outdoor mobility Mobility Level 3 - Suitable for people only able to manage 1 or 2 steps or stairs 1 bed flat ref no: 000 Landlord: Sovereign Supportive housing for individuals with diagnosed mental Rent: £87.17 per week health condition currently receiving support. -

Estuary Assessment

Appendix I Estuary Assessment Poole and Christchurch Bays SMP2 9T2052/R1301164/Exet Report V3 2010 Haskoning UK Ltd on behalf of Bournemouth Borough Council Poole & Christchurch Bays SMP2 Sub-Cell 5f: Estuary Processes Assessment Date: March 2009 Project Ref: R/3819/01 Report No: R.1502 Poole & Christchurch Bays SMP2 Sub-Cell 5f: Estuary Processes Assessment Poole & Christchurch Bays SMP2 Sub-Cell 5f: Estuary Processes Assessment Contents Page 1. Introduction....................................................................................................................1 1.1 Report Structure...........................................................................................................1 1.2 Literature Sources........................................................................................................1 1.3 Extent and Scope.........................................................................................................2 2. Christchurch Harbour ....................................................................................................2 2.1 Overview ......................................................................................................................2 2.2 Geology........................................................................................................................4 2.3 Holocene to Recent Evolution......................................................................................4 2.4 Present Geomorphology ..............................................................................................5 -

36 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

36 bus time schedule & line map 36 Talbot View - Bournemouth - Kinson View In Website Mode The 36 bus line (Talbot View - Bournemouth - Kinson) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Branksome: 7:00 AM - 5:23 PM (2) Kinson: 8:01 AM - 5:20 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 36 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 36 bus arriving. Direction: Branksome 36 bus Time Schedule 71 stops Branksome Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:00 AM - 5:23 PM Library, Kinson E52 (Site & Route of Pound Lane), Bournemouth Tuesday 7:00 AM - 5:23 PM Home Road, Kinson Wednesday 7:00 AM - 5:23 PM Tonge Road, Kinson Thursday 7:00 AM - 5:23 PM Wimborne Road, Bournemouth Friday 7:00 AM - 5:23 PM Anstey Close, Bear Cross Saturday 7:05 AM - 5:20 PM Anstey Close, Bournemouth Anchor Road, Bear Cross Cornerstone Church, Bear Cross 36 bus Info Direction: Branksome Elmrise School, Bear Cross Stops: 71 Trip Duration: 54 min Poole Lane, Turbary Common Line Summary: Library, Kinson, Home Road, Kinson, Tonge Road, Kinson, Anstey Close, Bear Cross, Travellers Lane, Turbary Common Anchor Road, Bear Cross, Cornerstone Church, Bear Cross, Elmrise School, Bear Cross, Poole Lane, Mandale Road, Turbary Common Turbary Common, Travellers Lane, Turbary Common, Mandale Road, Turbary Common, Gladdis Road, Turbary Common, Mandale Road Top, Turbary Gladdis Road, Turbary Common Common, Turbary Common Gate, Turbary Common, Turbary Park Flats, Turbary Common, Lydford Road, Mandale Road Top, Turbary Common Turbary -

Milford Drive, Bear Cross Bournemouth, Dorset BH11 9HJ

Milford Drive, Bear Cross Bournemouth, Dorset BH11 9HJ FREEHOLD PRICE “A beautifully modernised bungalow with a 60ft private south facing garden offered with no onward chain” £329,950 This recently modernised and superbly appointed three bedroom, two bathroom detached bungalow has an 18ft double glazed conservatory, 60ft private south facing rear garden, detached single garage and generous off road parking. Situated in a popular and convenient location close to all local amenities and offered with no onward chain. Spacious 19ft reception hall Generous size lounge with double glazed French doors leading out into the conservatory Re-fitted stunning modern kitchen incorporating ample wood block work surfaces, a good range of base and wall units, integrated oven, hob and extractor, recess for fridge, cupboard housing the newly installed Gloworm wall mounted gas fired boiler, fully tiled marble walls, polished porcelain tiled floor 18ft Double glazed newly constructed conservatory with polished porcelain tiled floor and double glazed French doors leading out into the private rear garden. Also in the conservatory there is space and plumbing for washing machine Master bedroom with a view over the front garden. Newly refitted and stylish en-suite shower room incorporating a good size shower cubicle, low level WC, wall mounted wash hand basin with vanity storage beneath, fully tiled walls with polished porcelain tiled floor Guest double bedroom enjoying a view over the front garden Good size third bedroom with a double glazed window to the side aspect Newly refitted family bathroom finished in a modern white suite incorporating a panelled bath with mixer taps and shower hose and glass shower screen, pedestal wash hand basin, fully tiled marble walls and mosaic tiled floor Separate cloakroom finished in a modern white suite with wood effect fully tiled walls and flooring The rear garden measures approximately 60ft in length x 35ft in width, faces a southerly aspect and offers an excellent degree of seclusion. -

Key to Advert Symbols

PROPERTY LIST All Partners Edition 410 The bidding deadline by which bids for properties in this cycle must reach us is before midnight on This property list shows you all of the available Monday 30 May 2016 vacancies across all the local authority partner areas within Dorset Home Choice. You will only be able to bid on properties that you are eligible for. For advice and assistance please contact your managing local authority partner Borough of Poole - 01202 633805 Bournemouth Borough Council - 01202 451467 Christchurch Borough Council - 01202 795213 East Dorset District Council - 01202 795213 North Dorset District Council - 01258 454111 Purbeck District Council - 01929 557370 West Dorset District Council - 01305 251010 Weymouth & Portland Borough Council - 01305 838000 Ways to bid (refer to the Scheme User Guide for more details) By internet at www.dorsethomechoice.org By telephone on 01202 454 700 By text message on 07781 472 726 KEY TO ADVERT SYMBOLS Available for Available for transferring Available for homeseekers homeseekers only tenants only and transferring tenants Number of bedrooms in the property Minimum and maximum number of Suitable for families people who can live in the property Floor level of property, Pets may be allowed with the No pets if flat or maisonette permission of the landlord allowed Garden Shared Lift No Lift Fixed Tenancy showing SHARED Garden number of years Property designed for people of this age or above Mobility Level 1 - Suitable for wheelchair users for full-time indoor and outdoor mobility Mobility Level 2 - Suitable for people who cannot manage steps, stairs or steep gradients and require a wheelchair for outdoor mobility Mobility Level 3 - Suitable for people only able to manage 1 or 2 steps or stairs 1 bed sheltered flat - Social rent ref no: 469 Moorlea, Wellington Road, Sprinbourne, Bournemouth Landlord: Bournemouth Housing Landlord Services Shared garden, electric central heating, bath. -

Dorset Pharmacy Email Addresses 01.04.20

Pharmacy Name Address 1 Address 2 Town County Postcode NHSmail Arrowedge Pharmacy 62 Poole Road Westbourne Bournemouth Dorset BH4 9DZ [email protected]; 188B Lower Arrowedge Pharmacy Blandford Road Broadstone Dorset BH18 8DP [email protected]; 12 Neighbourhood Centre, Culliford Arrowedge Pharmacy Crescent Canford Heath Poole Dorset BH17 9DW [email protected]; Asda Instore Pharmacy Newstead Road Weymouth Dorset DT4 8JQ [email protected]; Asda Pharmacy St Pauls Road Bournemouth Dorset BH8 8DL [email protected]; Asda Pharmacy West Quay Road Poole Poole Dorset BH15 1JQ [email protected]; 45 Wessex Trade Automeds Pharmacy Ltd Centre Ringwood Road Poole Dorset BH12 3PG [email protected]; Avicenna Pharmacy 63 Kinson Road Wallisdown Bournemouth Dorset BH10 4BX [email protected]; 24/26 Cunningham Avicenna Pharmacy Crescent West Howe Bournemouth Dorset BH11 8DU [email protected]; King John Unit 4 Bearwood Avenue, Avicenna Pharmacy Centre Bearwood Bournemouth Dorset BH11 9TW [email protected]; Beaminster Pharmacy 20 Hogshill Street Beaminster Dorset DT8 3AA [email protected]; 10-14 Salisbury Boots Pharmacy Street Blandford Dorset DT11 7AR [email protected]; 626-628 Boots Pharmacy Christchurch -

Water Situation Report Wessex Area

Monthly water situation report Wessex Area Summary – November 2020 Wessex received ‘normal’ rainfall in November at 84% LTA (71 mm). There were multiple bands of rain throughout November; the most notable event occurred on the 14 November, when 23% of the month’s rain fell. The last week of November was generally dry. The soil moisture deficit gradually decreased throughout November, ending the month on 7 mm, which is higher than the deficit this time last year, but lower than the LTA. When compared to the start of the month, groundwater levels at the end of November had increased at the majority of reporting sites. Rising groundwater levels in the Chalk supported the groundwater dominated rivers in the south, with the majority of south Wessex reporting sites experiencing ‘above normal’ monthly mean river flows, whilst the surface water dominated rivers in the north had largely ‘normal’ monthly mean flows. Daily mean flows generally peaked around 14-16 November in response to the main rainfall event. The dry end to November caused a recession in flows, with all bar two reporting sites ending the month with ‘normal’ daily mean flows. Total reservoir storage increased, with Wessex Water and Bristol Water ending November with 84% and 83%, respectively. Rainfall Wessex received 71 mm of rainfall in November (84% LTA), which is ‘normal’ for the time of year. All hydrological areas received ‘normal’ rainfall bar the Axe (69% LTA; 61 mm) and West Somerset Streams (71% LTA; 79 mm), which had ‘below normal’ rainfall. The highest rainfall accumulations (for the time of year) were generally in the east and south. -

DORSET's INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE Ulh 17

AfarsWs\?l ) •O ITNDUSTRIALONDUS TR I AL • 7/ 'rl/ f / 71 TO l) / vlJI/ b 1-/ |, / -] ) I ) ll ,, ' I ilittu It ,rtlll r ffi I ll I E l! ll l[! ll il- c t!H I I I H ltI --'t li . PETER. STANIER' SeIISIIOG IDVIIUIH IDVIIUIH DORSET'SIVIUISNONI INDUSTRIAL HERITAGE Jeled Peter Stanier JaruEls I r \ • r IT, LaS \-z'- rnol rnol 'r.pJV 'r.pJV lllPno lllPno Lano'ss,our1 Arch, Tout Quarry. INTRODUCTIONNOII)NCOU1NI lHt lINnol lINnol ,o ,o ;er'r1snpu| ]asJoc ]asJoc eql eql qlrr' qlrr' sr sr pa!.raluo) pa!.raluo) lSoloaeq:.re lSoloaeq:.re dn dn e e uorsr^ THE COUNTY of Dorset summonssuouJLLrns up a Industrial archaeology is concerned with the vision 1o lP.rn.r lP.rn.r ]sed ]sed re] plaleru sr;er )llllpr )llllpr ruorl ruorl lllpoedsa pa^ouJar pa^ouJar ue:,futsnpur, 'seqr^rpe s,ueul s,ueul puPl puPl far removed from)pq) 'industry': an idyllic rural land- material relics of man's past activities, especially lnq lnq op op u aq] u aq1 ur qlrM'edels pepoo^ pepoo^ su,^ su,^ qtuaalaLr qtuaalaLr Suruur8aq 'lrnluer 'lrnluer -rale^^ -rale^^ 'selP^ 'selP^ scape, with chalk downs, wooded vales, water- in the nineteenth century, but beginning in1o the aqt aqt ue ue Lnlua: Lnlua: d d aql aql anbsarnp anbsarnp sa8ell^ oppau] pouad pouad e8eur e8eur prur s,^ s,^ qluaatq8ra qluaatq8ra meadows andpLre picturesque villages — an image mid-eighteenth century — the period of the le-r]snpu lq lq jo jo eqt eqt se se euros euros qrns Ll)nLu seu.roqf seu.roqf s8uqr.r,,rl s8uqr.r,,rl pa)uequa pa)uequa 'serrlsnpllr 'serrlsnpllr much enhanced by the writings of Thomas Industrial -

RIDE 2 “Water Unwinds Old Ways Round Our Hills”

FEEL THE WIND ON YOUR FACE! Steep slopes & spectacular views. Wonderful butterfly habitat RIDE 2 and birdlife, especially skylarks. Ancient barrows and medieval field systems contribute to visible archaeology. Explore the Dorset The Frome Valley Downs on the footpaths above the Cerne and Sydling valleys. VILLAGE STROLLS Maiden Newton, Frampton & Sydling – pretty riverside villages “Water unwinds to visit. THE FAMOUS CERNE ABBAS GIANT The 180ft Giant shares the hillside above the village with Bronze old ways Age barrows and medieval field systems. One of the largest chalk figures in Britain, he is the most controversial. Is he an ancient symbol of spirituality, Roman Hercules or a fertility symbol? round our hills” With tea shops, pubs & riverside walks, Cerne Abbas is certainly worth a detour. The Frome Valley THOMAS HARDY’S HOUSES Walk in Hardy’s footsteps from his birthplace at Bockhampton to his grand house in Dorchester. Experience the heath and Following the River Frome and Sydling Water up and down their woodland which inspired his novels. nationaltrust.org.uk respective valleys and through water meadows. Look for traces DURNOVARIA OR DORCHESTER? of the Roman aqueduct which once brought water to Dorchester and Go back in time at Maiden Castle - largest hillfort in Britain which for the flash of Kingfishers, Marsh Marigolds and Brown Trout. is the size of 50 football pitches. Follow up with a trip to Dorset County Museum (Dorchester) to see the magnificent chieftains Ancient Sydling is pure Thomas Hardy Country, one of Dorset’s prettiest gold brooch or the Swanage crocodile or how the Romans lived villages.