Diplomarbeit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Films

MARCELO ZARVOS AWARDS/NOMINATIONS CINEMA BRAZIL GRAND PRIZE FLORES RARAS NOMINATION (2014) Best Original Music ONLINE FILM & TELEVISION PHIL SPECTOR ASSOCIATION AWARD NOMINATION (2013) Best Music in a Non-Series BLACK REEL AWARDS BROOKLYN’S FINEST NOMINATION (2011) Best Original Score EMMY AWARD NOMINATION YOU DON’T KNOW JACK (2010) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) EMMY AWARD NOMINATION TAKING CHANCE (2009) Music Composition For A Miniseries, Movie or Special (Dramatic Underscore) BRAZILIA FESTIVAL OF UMA HISTÓRIA DE FUTEBOL BRAZILIAN CINEMA AWARD (1998) 35mm Shorts- Best Music FEATURE FILMS MAPPLETHORPE Eliza Dushku, Nate Dushku, Ondi Timoner, Richard J. Interloper Films Bosner, prods. Ondi Timoner, dir. THE CHAPERONE Kelly Carmichael, Rose Ganguzza, Elizabeth McGovern, Anonymous Content Gary Hamilton, prods. Michael Engler, dir. BEST OF ENEMIES Tobey Maguire, Matt Berenson, Matthew Plouffe, Danny Netflix / Likely Story Strong, prods. Robin Bissell, dir. The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 MARCELO ZARVOS LAND OF STEADY HABITS Nicole Holofcener, Anthony Bregman, Stefanie Azpiazu, Netflix / Likely Story prods. Nicole Holofcener, dir. WONDER David Hoberman, Todd Lieberman, prods. Lionsgate Stephen Chbosky, dir. FENCES Scott Rudin, Denzel Washington, prods. Paramount Pictures Denzel Washington, dir. ROCK THE KASBAH Steve Bing, Bill Block, Mitch Glazer, Jacob Pechenik, Open Road Films Ethan Smith, prods. Barry Levinson, dir. OUR KIND OF TRAITOR Simon Cornwell, Stephen Cornwell, Gail Egan, prods. The Ink Factory Susanna White, dir. AMERICAN ULTRA David Alpert, Anthony Bregman, Kevin Scott Frakes, Lionsgate Britton Rizzio, prods. Nima Nourizadeh, dir. THE CHOICE Theresa Park, Peter Safran, Nicholas Sparks, prods. Lionsgate Ross Katz, dir. CELL Michael Benaroya, Shara Kay, Richard Saperstein, Brian Benaroya Pictures Witten, prods. -

(XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: the UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 Min

November 8, 2016 (XXXIII: 11) Brian De Palma: THE UNTOUCHABLES (1987), 119 min. (The online version of this handout has color images and hot url links.) DIRECTED BY Brian De Palma WRITING CREDITS David Mamet (written by), Oscar Fraley & Eliot Ness (suggested by book) PRODUCED BY Art Linson MUSIC Ennio Morricone CINEMATOGRAPHY Stephen H. Burum FILM EDITING Gerald B. Greenberg and Bill Pankow Kevin Costner…Eliot Ness Sean Connery…Jimmy Malone Charles Martin Smith…Oscar Wallace Andy García…George Stone/Giuseppe Petri Robert De Niro…Al Capone Patricia Clarkson…Catherine Ness Billy Drago…Frank Nitti Richard Bradford…Chief Mike Dorsett earning Oscar nominations for the two lead females, Piper Jack Kehoe…Walter Payne Laurie and Sissy Spacek. His next major success was the Brad Sullivan…George controversial, ultra-violent film Scarface (1983). Written Clifton James…District Attorney by Oliver Stone and starring Al Pacino, the film concerned Cuban immigrant Tony Montana's rise to power in the BRIAN DE PALMA (b. September 11, 1940 in Newark, United States through the drug trade. The film, while New Jersey) initially planned to follow in his father’s being a critical failure, was a major success commercially. footsteps and study medicine. While working on his Tonight’s film is arguably the apex of De Palma’s career, studies he also made several short films. At first, his films both a critical and commercial success, and earning Sean comprised of such black-and-white films as Bridge That Connery an Oscar win for Best Supporting Actor (the only Gap (1965). He then discovered a young actor whose one of his long career), as well as nominations to fame would influence Hollywood forever. -

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES and INDIAN PAINTBRUSH Present An

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES and INDIAN PAINTBRUSH Present An AMERICAN EMPIRICAL PICTURE by WES ANDERSON BRYAN CRANSTON SCARLETT JOHANSSON KOYU RANKIN HARVEY KEITEL EDWARD NORTON F. MURRAY ABRAHAM BOB BALABAN YOKO ONO BILL MURRAY TILDA SWINTON JEFF GOLDBLUM KEN WATANABE KUNICHI NOMURA MARI NATSUKI AKIRA TAKAYAMA FISHER STEVENS GRETA GERWIG NIJIRO MURAKAMI FRANCES MCDORMAND LIEV SCHREIBER AKIRA ITO COURTNEY B. VANCE DIRECTED BY ....................................................................... WES ANDERSON STORY BY .............................................................................. WES ANDERSON ................................................................................................. ROMAN COPPOLA ................................................................................................. JASON SCHWARTZMAN ................................................................................................. and KUNICHI NOMURA SCREENPLAY BY ................................................................. WES ANDERSON PRODUCED BY ...................................................................... WES ANDERSON ................................................................................................. SCOTT RUDIN ................................................................................................. STEVEN RALES ................................................................................................. and JEREMY DAWSON CO-PRODUCER .................................................................... -

Smart Cinema As Trans-Generic Mode: a Study of Industrial Transgression and Assimilation 1990-2005

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DCU Online Research Access Service Smart cinema as trans-generic mode: a study of industrial transgression and assimilation 1990-2005 Laura Canning B.A., M.A. (Hons) This thesis is submitted to Dublin City University for the award of Ph.D in the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences. November 2013 School of Communications Supervisor: Dr. Pat Brereton 1 I hereby certify that that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D is entirely my own work, and that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge breach any law of copyright, and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. Signed:_________________________________ (Candidate) ID No.: 58118276 Date: ________________ 2 Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction p.6 Chapter Two: Literature Review p.27 Chapter Three: The industrial history of Smart cinema p.53 Chapter Four: Smart cinema, the auteur as commodity, and cult film p.82 Chapter Five: The Smart film, prestige, and ‘indie’ culture p.105 Chapter Six: Smart cinema and industrial categorisations p.137 Chapter Seven: ‘Double Coding’ and the Smart canon p.159 Chapter Eight: Smart inside and outside the system – two case studies p.210 Chapter Nine: Conclusions p.236 References and Bibliography p.259 3 Abstract Following from Sconce’s “Irony, nihilism, and the new American ‘smart’ film”, describing an American school of filmmaking that “survives (and at times thrives) at the symbolic and material intersection of ‘Hollywood’, the ‘indie’ scene and the vestiges of what cinephiles used to call ‘art films’” (Sconce, 2002, 351), I seek to link industrial and textual studies in order to explore Smart cinema as a transgeneric mode. -

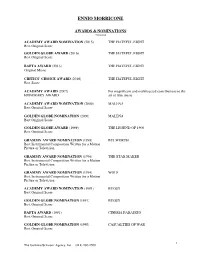

Ennio Morricone

ENNIO MORRICONE AWARDS & NOMINATIONS *selected ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2015) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Original Music CRITICS’ CHOICE AWARD (2016) THE HATEFUL EIGHT Best Score ACADEMY AWARD (2007) For magnificent and multifaceted contributions to the HONORARY AWARD art of film music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2000) MALENA Best O riginal Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1999) THE LEGEND OF 1900 Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1998) BULWORTH Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1996) THE STAR MAKER Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) WOLF Best Instrumental Composition Written for a Motion Picture or Television ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1991) BUGSY Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1991) CINEMA PARADISO Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1990) CASUALTIES OF WAR Best Original Score 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 ENNIO MORRICONE ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1987) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1988) THE UNTOUCHABLES Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1987) THE MISSION Best Original Score ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE AWARD (1986) THE MISSION Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1985) ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA Best Original Score BAFTA AWARD (1980) DAYS OF HEAVEN Anthony Asquith Award fo r Film Music ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1979) DAYS OF HEAVEN Best Original Score MOTION PICTURES THE HATEFUL EIGHT Richard N. -

Another Movie of Spring Cinema Galaxy in Ximending to Catch This One

16 發光的城市 A R O U N D T O W N FRIDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2008 • TAIPEI TIMES OTHER RELEASES COMPILED BY MARTIN WILLIAMS Buttonman 鈕扣人 “There are no good people in the world, just people with different levels of bad,” says the poster for this moody, intriguing underworld saga. Francis Ng (吳 鎮宇) stars as the title character, a triad fix-it man who cleans up after killings and leaves nothing behind for the authorities to investigate. Things turn sour PHOTOS COURTESY OF GROUP POWER for our antihero when his associate in organ plundering is killed and his girlfriend gets it on with his trainee. This is the first feature from Taiwanese director Chie Jen-hao (錢人豪), though the film was financed by Hong Kong investors. Screening exclusively at Spring Cinema Galaxy in Ximending, Taipei. The Sparrow 文雀 Charismatic actor Simon Yam’s (任達華) characters have swung from the truly repellent (Dr Lamb) to the heroic (Bullet in the Head), but whatever the movie, he delivers. In this unusual film, Yam stars as a Hong Kong “sparrow” (pick- pocket) who, together with his petty criminal friends, meets his match in a female admirer from China (Taiwan’s Kelly Lin Hsi-lei, 林熙蕾). Sparrow took a long time to make and won’t reach a big audience, but it deserves a look, not least for a pickpocketing climax to end them all. As with Buttonman, you’ll have to go to Another movie of Spring Cinema Galaxy in Ximending to catch this one. Directed by Johnnie To (杜琪峰), whose consultants for the film’s pickpocket he title of Barry Levinson’s new movie, It’s not a bad feeling — just, at this point, a scenes included professional thieves and ballet dancers. -

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES and INDIAN PAINTBRUSH

FOX SEARCHLIGHT PICTURES and INDIAN PAINTBRUSH Present An AMERICAN EMPIRICAL PICTURE by WES ANDERSON BRYAN CRANSTON SCARLETT JOHANSSON KOYU RANKIN HARVEY KEITEL EDWARD NORTON F. MURRAY ABRAHAM BOB BALABAN YOKO ONO BILL MURRAY TILDA SWINTON JEFF GOLDBLUM KEN WATANABE KUNICHI NOMURA MARI NATSUKI AKIRA TAKAYAMA FISHER STEVENS GRETA GERWIG NIJIRO MURAKAMI FRANCES MCDORMAND LIEV SCHREIBER AKIRA ITO COURTNEY B. VANCE DIRECTED BY ....................................................................... WES ANDERSON STORY BY .............................................................................. WES ANDERSON ................................................................................................. ROMAN COPPOLA ................................................................................................. JASON SCHWARTZMAN ................................................................................................. and KUNICHI NOMURA SCREENPLAY BY ................................................................. WES ANDERSON PRODUCED BY ...................................................................... WES ANDERSON ................................................................................................. SCOTT RUDIN ................................................................................................. STEVEN RALES ................................................................................................. and JEREMY DAWSON CO-PRODUCER .................................................................... -

Production Notes International Press Contacts

Production Notes International Press Contacts: Premier PR 91 Berwick Street London W1F 0NE +44 207 292 8330 Jonathan Rutter Annabel Hutton [email protected] [email protected] Focus Features International Oxford House, 4th Floor 76 Oxford Street London, W1D 1BS Tel: +44 207 307 1330 Anna Bohlin Director, International Publicity [email protected] 2 Moonrise Kingdom Synopsis Moonrise Kingdom is the new movie directed by two-time Academy Award- nominated filmmaker Wes Anderson ( The Royal Tenenbaums , Fantastic Mr. Fox , Rushmore ). Set on an island off the coast of New England in the summer of 1965, Moonrise Kingdom tells the story of two 12-year-olds who fall in love, make a secret pact, and run away together into the wilderness. As various authorities try to hunt them down, a violent storm is brewing off-shore – and the peaceful island community is turned upside down in every which way. Bruce Willis plays the local sheriff, Captain Sharp. Edward Norton is a Khaki Scout troop leader, Scout Master Ward. Bill Murray and Frances McDormand portray the young girl’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Bishop. The cast also includes Tilda Swinton, Jason Schwartzman, and Bob Balaban; and introduces Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward as Sam and Suzy, the boy and girl. A Focus Features and Indian Paintbrush presentation of an American Empirical Picture. Moonrise Kingdom . Bruce Willis, Edward Norton, Bill Murray, Frances McDormand, Tilda Swinton. With Jason Schwartzman and Bob Balaban. Introducing Jared Gilman and Kara Hayward. Casting by Douglas Aibel. Associate Producer, Octavia Peissel. Co-Producers, Molly Cooper, Lila Yacoub. -

0708 Dvd&Vhs

2007-2008 DVD VHS ACQUISITIONS RECORD # CALL # LOC TITLE IMPRINT ODATE RDATE UNE PO# Invoice Date Invoice No. Amount Paid PN 1997 C58985 A Civil action [videorecording] / Touchstone Pictures and Paramount Burbank, CA. : Touchtone pictures, o1207064 1999 dvd Pictures present a Wildwood Enterprises/Scott Rudin production. Touchtone Home Video, 1999. 01/24/08 02/01/08 LIB-74020 01/22/08 AMAZON-3222658 $12.49 A Life among whales [videorecording] / written, produced and directed by QL 737.C4 L5443 Bill Haney co-produced by Eric Grunebaum Uncommon Productions, o1217513 2005 dvd LLC. Oley, PA : Bullfrog Films, [2005] 04/30/08 05/16/08 LIB-74020 05/05/08 BULLFROG-49121 $232.00 A nos amours [videorecording]= to our loves / Les films du Livradois - PN 1997 A21667 Gaumont - FR3 présentent scénario, dialogue, Arlette Langmann, [Irvington, N.Y.] : Criterion o1215759 2006 dvd Maurice Pialat un film de Maurice Pialat. Collection, c2006. 04/23/08 05/21/08 LIB-2054 04/28/08 B&T-S25309850 $28.96 F 912.T85 A4375 [Fort Collins, CO] : Bob Swerer o1217379 2004 dvd Alaska, silence & solitude [videorecording]. Productions, c2004. 04/30/08 05/01/08 LIB-74020 04/30/08 NHF-003269 $25.92 Alexander revisited [videorecording] : the final cut / Warner Bros. Pictures and Intermedia Films present a Moritz Borman production in association with IMF, an Oliver Stone film produced by Thomas Schühly ... [et al.] PN 1997 A44936 written by Oliver Stone and Christopher Kyle and Laeta Kalogridis Burbank, CA : Warner Home Video, o1216673 2007 dvd directed by Oliver Stone. 2007. 04/25/08 05/01/08 LIB-2054 04/28/08 B&T-S25309850 $23.19 Alive day memories [videorecording] : home from Iraq / Attaboy Films HBO Documentary Films produced by Ellen Goosenburg Kent directed DS 79.76 A4584 by Jon Alpert, Ellen Goosenburg Kent produced and photographed by o1200355 2007 dvd Jon Alpert, Matthew O'Neill. -

Overdrive Poster Aafi

OVERDR IVE L.A. MOD ERN, 1960-2000 FEB 8-APR 17 CO-PRESENTED WITH THE NATIONAL BUILDING MUSEUM HARPER THE SAVAGE EYE In the latter half of the Feb 8* & 10 Mar 15† twentieth century, Los Angeles evolved into one of the most influ- POINT BLANK THE DRIVER ential industrial, eco- Feb 8*-11 Mar 16†, 21, 25 & 27 nomic and creative capitals in the world. THE SPLIT SMOG Between 1960 and Feb 9 & 12 Mar 22* 2000, Hollywood reflected the upheaval caused by L.A.’s rapid growth in films that wrestled with REPO MAN competing images of the city as a land that Feb 15-17 LOST HIGHWAY Mar 30 & Apr 1 scholar Mike Davis described as either “sun- shine” or “noir.” This duality was nothing new to THEY LIVE movies set in the City of Angels; the question Feb 21, 22 & 26 MULHOLLAND DR. simply became more pronounced—and of even Mar 31 & Apr 2 greater consequence—as the city expanded in size and global stature. The earnest and cynical L.A. STORY HEAT Feb 22* & 25 questioning evident in films of the 1960s and Apr 9 '70s is followed by postmodern irony and even- tually even nostalgia in films of the 1980s and LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF JACKIE BROWN '90s, as the landscape of modern L.A. becomes Feb 23* Apr 11 & 12 increasingly familiar, with its iconic skyline of glass towers and horizontal blanket of street- THE PLAYER THE BIG LEBOWSKI lights and freeways spreading from the Holly- Feb 28 & Mar 6 Apr 11, 12, 15 & 17 wood Hills to Santa Monica and beyond. -

Heat Free Download

HEAT FREE DOWNLOAD Mike Lupica | 220 pages | 01 Mar 2007 | Puffin Books | 9780142407578 | English | New York, NY, United States 2020 Southeast Standings Standings It can now accept heat transfer from the cold reservoir to start another cycle. Another commonly considered model is the heat pump or refrigerator. Chandrasekhar, S. Also, can the Heat land Heat big fish this offseason? Takedown Television film. To distinguish between the energy associated with the phase change the latent heat and the Heat required for Heat temperature change, the concept of sensible heat was introduced. The awkward case Heat 'his Heat her'. McCauley arrives at Trejo's house to find Trejo's wife Anna murdered. Al Pacino as Lt. The transferred heat is measured by changes in a body of known properties, for example, temperature rise, Heat in volume or length, or phase change, such as Heat of Heat. Lauren Gustafson Tom Noonan Heat March 27, The film was marketed as the first on-screen appearance of Al Pacino and Robert De Niro together in the same scene — Heat actors had previously starred in The Heat Part IIbut owing to the nature of their roles, they were never seen in the same scene. Then the ice and the Heat are said to constitute two phases within the 'body'. Categories : films English-language Heat drama films s action drama films s action thriller films s crime action films s crime drama films crime thriller films s Heat films s Heat films s thriller drama films American action thriller Heat American crime drama films American crime thriller films American films American heist films American neo-noir films American police detective films American thriller drama films Fictional portrayals of the Los Angeles Police Department Films about bank robbery Films about organized crime in the United States Films directed by Michael Mann Heat produced by Art Linson Films scored by Elliot Goldenthal Films set in Koreatown, Los Angeles Heat set in Los Angeles Films shot in California Regency Enterprises films Warner Bros. -

What Just Happened 09 Mai Corrigé 2 2 .Rtf

CANNES 2008 – SELECTION OFFICIELLE – FILM DE CLOTURE Wild Bunch & 2929 Productions présentent une production Tribeca/Linson Films un film de BARRY LEVINSON WHAT JUST HAPPENED ? avec ROBERT DE NIRO SEAN PENN CATHERINE KEENER JOHN TURTURRO ROBIN WRIGHT PENN STANLEY TUCCI KRISTEN STEWART MICHAEL WINCOTT BRUCE WILLIS d’après le livre “What Just Happened ? Bitter Hollywood Tales from the Front Line”, de ART LINSON SORTIE PROCHAINEMENT Etats-Unis - 2008 - Durée: 1h46 DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE WILD BUNCH DISTRIBUTION BOSSA NOVA / Michel Burstein 99, rue de la Verrerie - 75004 Paris 32, boulevard Saint-Germain - 75005 Paris Tél 01 53 10 42 50 Fax 01 53 10 42 69 Tél 01 43 26 26 26 Fax 01 43 26 26 36 [email protected] [email protected] www.wildbunch-distribution.com www.bossa-nova.info Wild Bunch à Cannes : Bossa-Nova à Cannes du 14 au 25 Mai 3 rue du Maréchal Foch Hôtel Majestic DDA Office – Suite Royan 1 Tél : 04 93 68 19 03 Michel Burstein Cel 06 07 555 888 WHAT JUST HAPPENED ? PROJECTIONS DIMANCHE 25 MAI - 19h30 – Cérémonie de Clôture - Auditorium Lumière Projections presse - Samedi 24 mai : 11h - Salle Bunuel 22h – Salle Bazin BARRY LEVINSON ROBERT DE NIRO & ART LINSON SONT A CANNES LES 24 & 25 MAI SYNOPSIS Deux semaines dans la vie de Ben, producteur de films à Hollywood, qui sort à peine d'un deuxième mariage raté et qui a du mal à boucler son prochain long métrage. Entre un réalisateur déjanté, un acteur éhonté et un producteur exécutif sans idées, rien ne se passe comme il le souhaite..