Echo Chamber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook Free Marvel: Spider-Man 1000 Dot-To-Dot Book

Ebook Free Marvel: Spider-Man 1000 Dot-to-Dot Book Join your friendly neighborhood Spider-Man and all your favorite comic characters on a new adventure from best-selling dot-to-dot artist Thomas Pavitte. With 20 complex puzzles to complete, each consisting of at least 1,000 dots, Marvel fans will have hours of fun bringing Spidey and his friends, allies, and most villainous foes to life. Paperback: 48 pages Publisher: Thunder Bay Press; Act Csm edition (March 14, 2017) Language: English ISBN-10: 1626867852 ISBN-13: 978-1626867857 Product Dimensions: 9.9 x 0.4 x 13.9 inches Shipping Weight: 14.4 ounces (View shipping rates and policies) Average Customer Review: 5.0 out of 5 stars 2 customer reviews Best Sellers Rank: #405,918 in Books (See Top 100 in Books) #101 in Books > Arts & Photography > Drawing > Coloring Books for Grown-Ups > Comics & Manga #254 in Books > Humor & Entertainment > Puzzles & Games > Board Games #696 in Books > Humor & Entertainment > Puzzles & Games > Puzzles Thomas Pavitte is a graphic designer and experimental artist who often uses simple techniques to create highly complex pieces. He set an unofficial record for the most complex dot-to-dot drawing in 2011 with his version of the Mona Lisa in 6,239 dots. He lives and works in Melbourne, Australia. Best dot-to-dot artist around. I love Thomas Pavitte's books...I've bought 5 of them. These are therapy for my overstressed head (I have twin 5 year olds) and also will turn into fun, inexpensive art on his walls. -

"Marvel's First Deaf Superhero" (PDF)

Lastname 1 Firstname Lastname English 102 Dr. Williams 28 February 2018 Marvel’s First Deaf Superhero In December of 1999, Marvel first introduced their first deaf superhero going by the name of Echo in the comic Daredevil Vol.2 #9. Echo or alias name Maya Lopez is a Native American born girl who was born with the disability of hearing loss. Later in her story her father is killed by Wilson Fisk also known as the Kingpin who was her fathers partner in crime. Fisk adopts his daughter and raises her into the woman she is now. But the way he raised her was actually training her in order to counter and defeat the superhero the Daredevil, another superhero with a disability of blindness. Later on in the story she finds love with a man named Matt Murdock, a blind man who later in the story she finds out that he is the Daredevil and the man she loves. She finally realizes the lies she grew up with and summons hatred and defeats her adopted father the Kingpin. She then later becomes fond with Wolverine and adopts a new identity as a superhero named Ronin. The way Marvel employs their inspiration porn from the character Echo is by using her as a super crip in order to inspire and create a role model for kids and adults with disabilities all over the world and in the Marvel Universe. Superheroes with disabilities are often given other heightened senses and abilities if they are lacking one, which Echo is capable of. Echo is capable of seeing very clearly and even reading lips from videos or in person in which she can transcribe every conversation as if she could hear the whole conversation. -

Diary of a Vampeen

Vamp Chronicles DIARY OF A VAMPEEN Book One Christin M Lovell — DIARY OF A VAMPEEN Copyright © 2011 by Christin M Lovell Cover Image © konradbak This book may not be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission from the author. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. All characters and storylines are the property of the author and your support and respect is appreciated. The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author. — VAMP CHRONICLES Diary of a Vampeen Vamp Yourself for War Hit the Road Jack The Innocence of White (short) Vamp Versus Vamp Darkness Falls Reflections (short) Vigilante The Break of Dawn (coming soon!) — DIARY OF A VAMPEEN Imagine living a human charade for fifteen years and never knowing it. Imagine being provided less than a week to learn and accept your family’s true heritage before it overtook you. Alexa Jackson, Lexi, is abruptly thrown onto this roller coaster and quickly learns that she can’t change fate, regardless of how many lifetimes she is given. She will be transformed into a vampeen on her sixteenth birthday, she will be called upon to fulfill a greater destiny within the dangerous world of vampires, and she will have to risk heartbreak and rejection if she ever wants a chance at love with Kellan, whether she likes it or not. — This book is dedicated to my daughter, Kali. -

Representations of Disability in Dw Gregory's Dirty Pictures

BODILY DIFFERENCE, INTERDEPENDENCE, AND TOXIC HALF-LIVES: REPRESENTATIONS OF DISABILITY IN D.W. GREGORY’S DIRTY PICTURES , THE GOOD DAUGHTER , AND RADIUM GIRLS A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRADLEY STEPHENSON Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2015 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled BODILY DIFFERENCE, INTERDEPENDENCE, AND TOXIC HALF-LIVES: REPRESENTATIONS OF DISABILITY IN D.W. GREGORY’S DIRTY PICTURES , THE GOOD DAUGHTER , AND RADIUM GIRLS presented by Bradley Stephenson, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black ______________________________________ Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne _____________________________________ Dr. David Crespy _____________________________________ Dr. Julie Passanante Elman ____________________________________ Dr. Jeni Hart ___________________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The chapter that analyzes Dirty Pictures is a revision and expansion of my previous essay on this play that won the American Theatre and Drama Society 2012 Emerging Scholar’s award and the South Eastern Theatre Conference 2013 Young Scholar’s Award and is currently under editorial review for publication with Disability Studies Quarterly . A version of chapter on The Good Daughter has been published in the Journal of American Drama and Theatre , issue 27.2 in 2015. A portion of the chapter on Radium Girls was presented at Theatre Symposium in 2015 under the title, Toxic Actors: Animacy and Half-Life in D.W. Gregory’s Radium Girls. Special thanks to Cheryl for your guidance and leadership through this process. -

Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Grimoire University Publications Spring 2005 Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire Recommended Citation La Salle University, "Grimoire Vol. 44 Spring 2005" (2005). Grimoire. 14. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/grimoire/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Grimoire by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. spring 2005 volume 4 4 fetter from the editress “Staring at the blank page before you, Open up the dirty window, Let the sun illuminate the words that you could not find...” Each time the lyrics of Natasha Bedingfield’s “Unwritten” play over in my head, I can’t help but be reminded of the seemingly unattainable goals I dream up for myself every day. Not just the dream, but also the struggle to make those visions real— to voice the words and feelings that no one else can— quickly becomes more tiring and frustrating than life itself. Compared to the size of the whole, the simple goal of being published in this unknown, student-run maga zine is but a small accomplishment. This becomes obvious, as this book may eventually (and most likely will) pass from your hand, the reader’s, to the ground, or a trashcan, or— if we’re lucky— tossed out of a third-story dorm window. But the Grimoire is more than just a magazine— it’s a monument on which is carved the legacy of hundreds of students. -

The Path of Lucius Park and Other Stories of John Valley

THE PATH OF LUCIUS PARK AND OTHER STORIES OF JOHN VALLEY By Elijah David Carnley Approved: Sybil Baker Thomas P. Balázs Professor of English Professor of English (Chair) (Committee Member) Rebecca Jones Professor of English (Committee Member) J. Scott Elwell A. Jerald Ainsworth Dean of College of Arts and Sciences Dean of the Graduate School THE PATH OF LUCIUS PARK AND OTHER STORIES OF JOHN VALLEY By Elijah David Carnley A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Master’s of English The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chattanooga, Tennessee May 2013 ii Copyright © 2013 By Elijah David Carnley All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT This thesis comprises a writer’s craft introduction and nine short stories which form a short story cycle. The introduction addresses the issue of perspective in realist and magical realist fiction, with special emphasis on magical realism and belief. The stories are a mix of realism and magical realism, and are unified by characters and the fictional setting of John Valley, FL. iv DEDICATION These stories are dedicated to my wife Jeana, my parents Keith and Debra, and my brother Wesley, without whom I would not have been able to write this work, and to the towns that served as my home in childhood and young adulthood, without which I would not have been inspired to write this work. v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my Fiction professors, Sybil Baker and Tom Balázs, for their hard work and patience with me during the past two years. -

New Avengers, Vol. 8: Secret Invasion, Book 1 (V

New Avengers, Vol. 8: Secret Invasion, Book 1 (v. 8, Bk. 1) by Brian Michael Bendis ebook Ebook New Avengers, Vol. 8: Secret Invasion, Book 1 (v. 8, Bk. 1) currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook New Avengers, Vol. 8: Secret Invasion, Book 1 (v. 8, Bk. 1) please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Hardcover:::: 120 pages+++Publisher:::: Marvel (December 10, 2008)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 0785129464+++ISBN-13:::: 978- 0785129462+++Product Dimensions::::1 x 1 x 1 inches++++++ ISBN10 0785129464 ISBN13 978-0785129 Download here >> Description: The Skrulls, shape-shifting aliens led by their queen Veranke, have invaded the planet with information they learned from the Illuminati and, after surviving the House of M, Spider-Woman, the Hood, and the other Avengers fight back to save Earth. Collects The New Avengers (2005) # 38-425 single-issue stories related to Secret Invasion. Each issue is by a different artist, but theyre all good, so thats alright. The New Avengers and Mighty Avengers tie-in books were better than the main event book.38 Art by Michael G. - Luke Cage is not happy about Jessica Jones decision to go to Starks Tower.39 Art bt David Mack - Echo and Wolverine fight a Skrull with multiple superpowers.40 Pencils by Jim Cheung - What the Skrulls have been up to the past several years. Background on their queen. She decides to be part of the infiltration as a replacement for an Avenger.41 Art by Billy Tan - Ka-Zar and Shanna fight Skrulls in the Savage Land.42 Pencils by Jim Cheung - Continues the story of the Skrull queen in her new guise on Earth. -

A Qualitative Content Analysis of How Superheroines Are Portrayed in Comic Books

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Fight Like a Girl: A Qualitative Content Analysis of How Superheroines are Portrayed in Comic Books A graduate project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology By Kimberly Romero December 2020 Copyright by Kimberly Romero 2020 ii The graduate project of Kimberly Romero is approved: _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Michael Carter Date _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Stacy Missari Date _________________________________________ ______________ Dr. Moshoula Capous-Desyllas, Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to start off by acknowledging my parents for braving through a civil war, poverty, pain, political criticisms, racial stereotypes, and the constant bouts of uncertainty that immigrating to the United States, seeking asylum from the dangers plaguing their home country of El Salvador, has presented them with throughout the years. If it were not for your sacrifices, we would not have the lives and opportunities we have now. Having your constant love and support means the world to me. You are both my North Stars for everything I do. I would also like to acknowledge my sister for convincing Mom and Dad to let you name me after two of your greatest childhood role models, superheroines, and cultural icons. The Pink Power Ranger and The Queen of Tejano music are both pretty huge namesakes to live up to. I hope I do their legacies justice and that I am making you proud. I know I do not say this to you often but know that, through all our ups and downs, you were my hero growing up. -

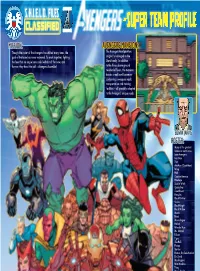

–Super Team Profile

interve rd nt za io AvengErS a n H e c S i p g i o e n t S.H.I.E.L.D. FILES a a r g t e S • • –SUPER TEAM PROFILE iniTiaTiVE L CLASSIFIED o e g t i a st or ics Direct miSSion: AvengErS manSion: Though the roster of the Avengers has shifted many times, the The Avengers headquarters goal of the team has never wavered. To work together, fighting originally belonged to the the foes that no single hero could withstand! For now, and Stark family. In addition forever, they heed the call – Avengers Assemble! to the three above-ground residential floors, the mansion boasts a multilevel basement containing a weapons vault, transportation and training facilities — all specially adapted to the Avengers’ unique needs. EDWin JarViS roster: Many of the greatest heroes on earth have been Avengers: Iron Man Thor Ant-Man (Giant-Man) Wasp Hulk Captain America Hawkeye Scarlet Witch Quicksilver Swordsman Hercules Black Panther Vision Black Knight Black Widow Mantis Beast Moondragon Hellcat Wonder Man Ms. Marvel Falcon Tigra She-Hulk Photon Starfox Namor, the Sub-Mariner Dr. Druid Mockingbird War Machine Thing Moon Knight Firebird D-Man Gilgamesh Mr. Fantastic Invisible Woman U.S.Agent Quasar Human Torch Sersi Stingray Spider-Man Sandman Rage Machine Man Living Lightning Spider-Woman II Crystal Thunderstrike Darkhawk Justice Firestar Triathlon Jack of Hearts Ant-Man II Lionheart Luke Cage Wolverine Sentry Echo Ares Jocasta Stature Vision II Bucky Barnes Spider-Woman I Valkyrie Ant-Man III Sharon Carter Nova Captain Britain Iron Fist Power Woman Protector Dr. -

Utah State University Undergraduate Student Fieldwork Collection, 1979-2017

Utah State University undergraduate student fieldwork collection, 1979-2017 Overview of the Collection Creator Fife Folklore Archives. Title Utah State University undergraduate student fieldwork collection Dates 1979-2017 (inclusive) 1979 2015 Quantity 54 linear feet, (115 boxes) Collection Number USU_FOLK COLL 8: USU Summary Folklore projects collected by Utah State University students in fulfillment of graded credit requirements for coursework in undergraduate folklore classes (1979 to present). Repository Utah State University, Merrill-Cazier Library, Special Collections and Archives Division Special Collections and Archives Merrill-Cazier Library Utah State University Logan, UT 84322-3000 Telephone: 435-797-2663 Fax: 435-797-2880 [email protected] Access Restrictions Restrictions Open to public research. To access the collection a patron must have the following information: collection number, box number and folder number. The materials do not circulate and are available in USU's Special Collections and Archives. Patrons must sign and comply with the USU Special Collections and Archives Use Agreement and Reproduction Order form as well as any restrictions placed by the collector or informant(s). Languages English. Sponsor Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA) grant, 2007-2008 Historical Note The Utah State University Undergraduate Student Fieldwork Collection consists of USU student folklore projects from 1979 to the present. The collection continues to grow. Content Description The Utah State University Undergraduate Student Fieldwork -

This Was Paw-Paw” and “Family Comes First, Trev” and “Yeah, He’S at the House; Don’T Worry About It.” Their Conversation Had Interested Me the Most, Honestly

CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Epilogue Acknowledgments About the Author Also Available MARIANA ZAPATA Hands Down © 2020 Mariana Zapata All rights reserved. In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the author is unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. This e-book is a work of fiction. While reference might be made to actual historical events or existing locations, the names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 2020 Mariana Zapata Book Cover Design by RBA Designs Editing by Hot Tree Editing and My Brother’s Editor To my greatest friend and teacher. The absolute love of my life. Dorian, this book and my whole life is dedicated to your memory. CHAPTER ONE “The word is out! The Oklahoma Thunderbirds have signed quarterback Damarcus Williams to a two-year deal worth $25 million. This move comes weeks after the organization announced that Zac Travis would enter free agency following five seasons in Oklahoma City. -

Environmental Crimes

Environmental Crimes In This Issue Introduction to the Environmental Crimes Issue of the USA Bulletin . .1 By Ignacia S. Moreno July 2011 Environmental Justice in the Context of Environmental Crimes . .3 Volume 59 By Kris Dighe and Lana Pettus Number 4 United States Post Flores-Figueroa: The Impact on the Knowing Mental State in Department of Justice Executive Office for Environmental Prosecutions . .15 United States Attorneys Washington, DC By Linda S. Kato and Patricia W. Davies 20530 H. Marshall Jarrett Director An Accident Waiting to Happen? Prosecuting Negligence-Based Environmental Crimes . 33 Contributors' opinions and statements should not be By Stacey P. Geis considered an endorsement by EOUSA for any policy, program, or service. Prosecuting Criminal Violations of the Endangered Species Act . .46 The United States Attorneys' Bulletin is published pursuant to 28 By Marshall Silverberg and Ethan Carson Eddy CFR § 0.22(b). The United States Attorneys' Achieving Worker Safety Through Environmental Crimes Prosecutions .58 Bulletin is published bimonthly by the Executive Office for By Deborah L. Harris United States Attorneys, Office of Legal Education, 1620 Pendleton Street, Columbia, South Carolina 29201. Prosecuting Industrial Takings of Protected Avian Wildlife . 65 By Robert S. Anderson and Jill Birchell Managing Editor Jim Donovan The Soothsayer, Julius Caesar, and Modern Day Ides: Why You Should Law Clerk Carmel Matin Prosecute FIFRA Cases . .84 Internet Address By Jared C. Bennett www.usdoj.gov/usao/ reading_room/foiamanuals. html The Lacey Act Amendments of 2008: Curbing International Trafficking Send article submissions and address changes to Managing in Illegal Timber . .91 Editor, United States Attorneys' Bulletin, By Elinor Colbourn and Thomas W.