Research.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journalism's Backseat Drivers. American Journalism

V. Journalism's The ascendant blogosphere has rattled the news media with its tough critiques and nonstop scrutiny of their reporting. But the relationship between the two is nfiore complex than it might seem. In fact, if they stay out of the defensive crouch, the battered Backseat mainstream media may profit from the often vexing encounters. BY BARB PALSER hese are beleaguered times for news organizations. As if their problems "We see you behind the curtain...and we're not impressed by either with rampant ethical lapses and declin- ing readership and viewersbip aren't your bluster or your insults. You aren't higher beings, and everybody out enough, their competence and motives are being challenged by outsiders with here has the right—and ability—to fact-check your asses, and call you tbe gall to call them out before a global audience. on it when you screw up and/or say something stupid. You, and Eason Journalists are in the hot seat, their feet held to tbe flames by citizen bloggers Jordan, and Dan Rather, and anybody else in print or on television who believe mainstream media are no more trustwortby tban tbe politicians don't get free passes because you call yourself journalists.'" and corporations tbey cover, tbat journal- ists tbemselves bave become too lazy, too — Vodkapundit blogger Will Collier responding to CJR cloistered, too self-rigbteous to be tbe watcbdogs tbey once were. Or even to rec- Daily Managing Editor Steve Lovelady's characterization ognize what's news. Some track tbe trend back to late of bloggers as "salivating morons" 2002, wben bloggers latcbed onto U.S. -

Salem Media Announces New Leadership in Dallas

November 17, 2016 Salem Media Announces New Leadership in Dallas CAMARILLO, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Salem Media Group (NASDAQ: SALM), announced today that Jeff Mitchell has been appointed to General Manager for Salem Media Group’s stations in Dallas. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20161117005962/en/ Jeff has been with Salem Dallas as Director of Sales for the past 6 ½ years. His overall radio experience spans 25 years and includes stints at CBS and iHeart. Having lived in Dallas for 11 years, Jeff is well-entrenched and respected throughout the advertising community. Salem Senior Vice President, Linnae Young, commented, “We are excited to have Jeff at the helm in Dallas. He has consistently demonstrated strategic, effective leadership.” Follow us on Twitter @SalemMediaGrp. ABOUT SALEM MEDIA GROUP: Salem Media Group is America’s leading multimedia company specializing in Christian and conservative content, with media properties comprising radio, digital media and book, magazine and newsletter publishing. Each day Salem Jeff Mitchell (Photo: Business Wire) serves a loyal and dedicated audience of listeners and readers numbering in the millions nationally. With its unique programming focus, Salem provides compelling content, fresh commentary and relevant information from some of the most respected figures across the media landscape. The company, through its Salem Radio Group, is the largest commercial U.S. radio broadcasting company providing Christian and conservative programming. Salem owns and operates 118 local radio stations, with 73 stations in the top 25 media markets. Salem Radio Network (“SRN”) is a full-service national radio network, with nationally syndicated programs comprising Christian teaching and talk, conservative talk, news, and music. -

Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy

The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy Dr. Valerie Scatamburlo-D'Annibale University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada Abstract This article explores how Donald Trump capitalized on the right's decades-long, carefully choreographed and well-financed campaign against political correctness in relation to the broader strategy of 'cultural conservatism.' It provides an historical overview of various iterations of this campaign, discusses the mainstream media's complicity in promulgating conservative talking points about higher education at the height of the 1990s 'culture wars,' examines the reconfigured anti- PC/pro-free speech crusade of recent years, its contemporary currency in the Trump era and the implications for academia and educational policy. Keywords: political correctness, culture wars, free speech, cultural conservatism, critical pedagogy Introduction More than two years after Donald Trump's ascendancy to the White House, post-mortems of the 2016 American election continue to explore the factors that propelled him to office. Some have pointed to the spread of right-wing populism in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis that culminated in Brexit in Europe and Trump's victory (Kagarlitsky, 2017; Tufts & Thomas, 2017) while Fuchs (2018) lays bare the deleterious role of social media in facilitating the rise of authoritarianism in the U.S. and elsewhere. Other 69 | P a g e The 'Culture Wars' Reloaded: Trump, Anti-Political Correctness and the Right's 'Free Speech' Hypocrisy explanations refer to deep-rooted misogyny that worked against Hillary Clinton (Wilz, 2016), a backlash against Barack Obama, sedimented racism and the demonization of diversity as a public good (Major, Blodorn and Blascovich, 2016; Shafer, 2017). -

Restoring the Ideal Marketplace: How Recognizing Bloggers As Journalists Can Save the Press

\\server05\productn\N\NYL\9-2\NYL202.txt unknown Seq: 1 17-OCT-06 15:39 RESTORING THE IDEAL MARKETPLACE: HOW RECOGNIZING BLOGGERS AS JOURNALISTS CAN SAVE THE PRESS Joseph S. Alonzo* INTRODUCTION In May 2006, a California state appeals court became the first court to explicitly recognize that Internet journalists are afforded the same journalist’s privilege granted to traditional print and broadcast journalists. The defendants in O’Grady v. Superior Court maintained individual websites on which they published trade secrets about an unreleased Apple Computer (Apple) product.1 Unanimously overrul- ing the trial court, the appeals court held that the petitioners were pro- tected by California’s reporter’s shield law and the constitutional journalist’s privilege from being forced to testify about the identity of their sources.2 Because they were publishers of websites, and because they had published not news but the fruits of “trade secret misappropriation,” Apple argued petitioners were not “engaged in legitimate journalistic activities” and were not part of the class of persons protected by the California’s shield law.3 The court determined, however, that the peti- * J.D., 2006, New York University School of Law; B.A., B.J., University of Mis- souri, 2003. Many thanks to Professor Diane Zimmerman and to my colleagues on the New York University Journal of Legislation and Public Policy, for their assistance and for putting up with me. 1. O’Grady v. Superior Court, 44 Cal. Rptr. 3d 72 (Cal. Ct. App. 2006). 2. Id. at 76. 3. Id. at 96–97. As the court explained, the California reporter’s shield is com- prised of two substantially similar sources of law: Article I, section 2, subdivision (b), of the California Constitution pro- vides, “A publisher, editor, reporter, or other person connected with or employed upon a newspaper, magazine, or other periodical publica- tion . -

(A Thousand Points Of) Light on Biased Language

Shedding (a Thousand Points of) Light on Biased Language Tae Yano Philip Resnik School of Computer Science Department of Linguistics and UMIACS Carnegie Mellon University University of Maryland Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA College Park, MD 20742, USA [email protected] [email protected] Noah A. Smith School of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA [email protected] Abstract To what extent a sentence or clause is biased (none, • somewhat, very); This paper considers the linguistic indicators of bias in political text. We used Amazon Mechanical Turk The nature of the bias (very liberal, moderately lib- • judgments about sentences from American political eral, moderately conservative, very conservative, bi- blogs, asking annotators to indicate whether a sen- ased but not sure which direction); and tence showed bias, and if so, in which political di- rection and through which word tokens. We also Which words in the sentence give away the author’s asked annotators questions about their own political • views. We conducted a preliminary analysis of the bias, similar to “rationale” annotations in Zaidan et data, exploring how different groups perceive bias in al. (2007). different blogs, and showing some lexical indicators strongly associated with perceived bias. For example, a participant might identify a moderate liberal bias in this sentence, 1 Introduction Without Sestak’s challenge, we would have Bias and framing are central topics in the study of com- Specter, comfortably ensconced as a Democrat munications, media, and political discourse (Scheufele, in name only. 1999; Entman, 2007), but they have received relatively adding checkmarks on the underlined words. -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

Fact Or Fiction?

The Ins and Outs of Media Literacy 1 Part 1: Fact or Fiction? Fake News, Alternative Facts, and other False Information By Jeff Rand La Crosse Public Library 2 Goals To give you the knowledge and tools to be a better evaluator of information Make you an agent in the fight against falsehood 3 Ground rules Our focus is knowledge and tools, not individuals You may see words and images that disturb you or do not agree with your point of view No political arguments Agree 4 Historical Context “No one in this world . has ever lost money by underestimating the intelligence of the great masses of plain people.” (H. L. Mencken, September 19, 1926) 5 What is happening now and why 6 Shift from “Old” to “New” Media Business/Professional Individual/Social Newspapers Facebook Magazines Twitter Television Websites/blogs Radio 7 News Platforms 8 Who is your news source? Professional? Personal? Educated Trained Experienced Supervised With a code of ethics https://www.spj.org/ethicscode.asp 9 Social Media & News 10 Facebook & Fake News 11 Veles, Macedonia 12 Filtering Based on: Creates filter bubbles Your location Previous searches Previous clicks Previous purchases Overall popularity 13 Echo chamber effect 14 Repetition theory Coke is the real thing. Coke is the real thing. Coke is the real thing. Coke is the real thing. Coke is the real thing. 15 Our tendencies Filter bubbles: not going outside of your own beliefs Echo chambers: repeating whatever you agree with to the exclusion of everything else Information avoidance: just picking what you agree with and ignoring everything else Satisficing: stopping when the first result agrees with your thinking and not researching further Instant gratification: clicking “Like” and “Share” without thinking (Dr. -

Won't Make Hundreds of Millions of Dollars While Their Employees Are Below the Poverty Line

won't make hundreds of millions of dollars while their employees are below the poverty line. Hillary said "We are going to take things away from you for the common good." Goddess bless her. We need stations like WTPG to show the masses what we liberals Dlan to do to helD this countw. Jeff Coryell 44118 The progressive community in Columbus is vibrant and growing. More and more Ohioans are seeing through the empty right wing spin and coming around to the common-sense progressive agenda. They need a radio station that respects their point of view! ~oan Fluharty 43068 Sara Richman 01940 Progressive Talk Radio sserves an imponant for the public to hear another side of the issues. Talk radio is "lopsidedly" one sided and as we know, this is extremely dangerous in a democracy. Boston lost their Progressive Talk Radio and I feel as if I lost a friend. Out of habit, when I turn to the station in the car or in the kitchen, I get annoying rumba music. I wish a petition could be started to have another Boston station broadcast Progressive Talk. I khank you, Sara Richman Karl lKav 143232 IProqressive radio is imDonant in Central Ohio because someone has to tell They are more than willing to patronize any advenisers to the channel. arilyn eerman Franken and Schultz have reg Iavis 1230 since it started in Columbus in September 2004. On average, we e listened to AM1230 for eight to ten hours a day (my wife listens to it a 1230, as have many of our friends and acquaintances. -

(Pdf) Download

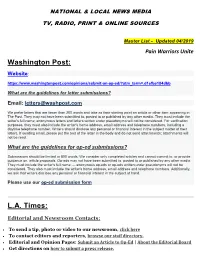

NATIONAL & LOCAL NEWS MEDIA TV, RADIO, PRINT & ONLINE SOURCES Master List - Updated 04/2019 Pain Warriors Unite Washington Post: Website: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/submit-an-op-ed/?utm_term=.d1efbe184dbb What are the guidelines for letter submissions? Email: [email protected] We prefer letters that are fewer than 200 words and take as their starting point an article or other item appearing in The Post. They may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name; anonymous letters and letters written under pseudonyms will not be considered. For verification purposes, they must also include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers, including a daytime telephone number. Writers should disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject matter of their letters. If sending email, please put the text of the letter in the body and do not send attachments; attachments will not be read. What are the guidelines for op-ed submissions? Submissions should be limited to 800 words. We consider only completed articles and cannot commit to, or provide guidance on, article proposals. Op-eds may not have been submitted to, posted to or published by any other media. They must include the writer's full name — anonymous op-eds or op-eds written under pseudonyms will not be considered. They also must include the writer's home address, email address and telephone numbers. Additionally, we ask that writers disclose any personal or financial interest in the subject at hand. Please use our op-ed submission form L.A. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

STAN ANTONIUS VEUGER (Last Updated: November 5, 2019)

STAN ANTONIUS VEUGER (last updated: November 5, 2019) Resident Scholar, Economic Policy Studies [email protected] American Enterprise Institute Phone: 202-862-5894 1789 Massachusetts Avenue NW http://www.aei.org/veuger Washington, DC 20036 Twitter: @stanveuger Professional Experience Fall 2019 Visiting Lecturer of Economics, Harvard University 2018-Present Extramural Fellow, Department of Economics, Tilburg University 2017-Present CGC Future World Fellow, IE School of Global and Public Affairs, IE University 2015-Present Editor, AEI Economic Perspectives 2013-Present Resident Scholar, American Enterprise Institute Fall 2018 Visiting Lecturer of Economics, Harvard University 2016-2018 Expert, expertpowerhouse Fall 2016 Visiting Lecturer of Economics, Harvard University 2014-2016 Advisor, Global Horizon Advisory 2012-2013 Research Fellow, American Enterprise Institute 2012-2013 Washington Fellow, National Review Institute 2008-2011 Teaching Fellow, Harvard University 2007 Research Assistant, Harvard University 2005-2006 Teaching Assistant, Universitat Pompeu Fabra Education Ph.D., Economics, Harvard University, 2012 A.M., Economics, Harvard University, 2009 (fields: Public Economics and International Economics) M.Sc., Economics, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Honors, 2005 Master’s in International Management, CEMS - Global Alliance in Management Education, 2004 Doctorandus, Spanish Language and Literature, Universiteit Utrecht, cum laude, 2004 Doctorandus, Business Administration, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 2004 Peer-Reviewed Publications “Taking My Talents to South Beach (and Back): Evidence from a Superstar Athlete,” (2019) Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics 22:12, 1950-1960. Joint with Daniel Shoag. “Rules versus Home Rule: Local Government Responses to Negative Revenue Shocks,” (2019) National Tax Journal 72:3, 543-574. Joint with Daniel Shoag and Cody Tuttle. “Do Land Use Restrictions Increase Restaurant Quality and Diversity?” (2019) Journal of Regional Science 59:3, 435-451. -

The Political Blogosphere and the 2004 U.S. Election: Divided They Blog

The Political Blogosphere and the 2004 U.S. Election: Divided They Blog Lada A. Adamic Natalie Glance HP Labs Intelliseek Applied Research Center 1501 Page Mill Road Palo Alto, CA 94304 5001 Baum Blvd. Pittsburgh, PA 15217 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT four internet users in the U.S. read weblogs, but 62% of them In this paper, we study the linking patterns and discussion still did not know what a weblog was. During the presiden- topics of political bloggers. Our aim is to measure the degree tial election campaign many Americans turned to the Inter- of interaction between liberal and conservative blogs, and to net to stay informed about politics, with 9% of Internet users uncover any differences in the structure of the two commu- saying that they read political blogs “frequently” or “some- times”2. Indeed, political blogs showed a large growth in nities. Specifically, we analyze the posts of 40 “A-list” blogs 3 over the period of two months preceding the U.S. Presiden- readership in the months preceding the election. tial Election of 2004, to study how often they referred to Recognizing the importance of blogs, several candidates one another and to quantify the overlap in the topics they and political parties set up weblogs during the 2004 U.S. discussed, both within the liberal and conservative commu- Presidential campaign. Notably, Howard Dean’s campaign nities, and also across communities. We also study a single was particularly successful in harnessing grassroots support day snapshot of over 1,000 political blogs. This snapshot using a weblog as a primary mode for publishing dispatches captures blogrolls (the list of links to other blogs frequently from the candidate to his followers.