Kelley Elzinga MAVCS Project Proposal "The Cultural Impact Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cosmetics in Sulphur, Nevada a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of

University of Nevada, Reno Keeping Up Appearances: Cosmetics in Sulphur, Nevada A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology by Chelsea N. Banks Dr. Carolyn White/Thesis Advisor August, 2011 © by Chelsea N. Banks 2011 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by CHELSEA N. BANKS entitled Keeping Up Appearances: Cosmetics In Sulphur, Nevada be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Dr. Carolyn White, Advisor Dr. Donald Hardesty, Committee Member Dr. Elizabeth Raymond, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Dean, Graduate School August, 2011 i Abstract Sulphur, Nevada is an abandoned mining settlement in northwestern Nevada that was settled in the early 20th century. Archaeological work conducted at the site in 2009 and 2010 revealed the presence of an unusual number of beauty-related artifacts, including artifacts related to skin and hair care. These artifacts suggest a significant use of cosmetics by former residents. Cosmetics and other beauty aids represent an important marker for cultural change, particularly in the early 20th century, when changes in cosmetics use reflected changing values regarding gender and identity. In the context of gender theory and world systems theory, cosmetics provide insight into how Sulphur residents responded to and connected with the larger world. The cosmetics discovered at Sulphur demonstrate that Sulphur residents were aware of and participated with the outside world, but did so according to their own needs. ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank all those who helped this thesis project come about. -

Growth of Women's Cosmetics(PDF: 436

Special Feature Growth of Women’s Cosmetics Becoming More Attractive to Women Domestic and overseas women’s products are enjoying strong sales, driving the overall Group. We continue to develop our brands, focused mainly on Japan and Asia. Brands include Bifesta, which makes beauty simple; Pixy, a comprehensive lineup of cosmetic products for sophisticated women; Lúcido-L, a hair care brand for young women; and Pucelle, a fragrance and body care brand for young women newly conscious of fashion and glamour. Sales have exceeded ¥19 billion, 1.6 times the level of five years ago, and comprise more than 25% of net sales 1In the domestic men’s cosmetics market, Mandom Women’s Cosmetics Business + Women’s Cosmetries Business boasts the top market share in three categories: Net sales (Millions of yen) hair styling, face care and body care. Mandom is well recognized as a men’s cosmetics + manufacturer, but in recent years we have been 63% channeling resources into the women’s cosmetics market, and this has boosted earnings. 19,053 Our entry into the market started with the 16,171 14,376 launch of our Pixy brand in Indonesia in 1982, and 12,487 in 1993 in Japan with the launch of Lúcido-L, a 11,690 hair care brand for women. Relying on a process of trial and error over the past 35 years, Mandom has undertaken research targeting women’s cosmetics. Our efforts resulted in 2005 in the launch of Perfect Assist 24, 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Mandom’s first proprietary cosmetic product (Years ended March 31) in Japan for women, and the launch of Bifesta in 2011. -

Advertising, Women, and Censorship

Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality Volume 11 Issue 1 Article 5 June 1993 Advertising, Women, and Censorship Karen S. Beck Follow this and additional works at: https://lawandinequality.org/ Recommended Citation Karen S. Beck, Advertising, Women, and Censorship, 11(1) LAW & INEQ. 209 (1993). Available at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/lawineq/vol11/iss1/5 Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality is published by the University of Minnesota Libraries Publishing. Advertising, Women, and Censorship Karen S. Beck* I. Introduction Recently, a friend told me about a television commercial that so angers her that she must leave the room whenever it airs. The commercial is for young men's clothing and features female mod- els wearing the clothes - several sizes too large - and laughing as the clothes fall off, leaving the women clad in their underwear. A male voice-over assures male viewers (and buyers) that the cloth- ing company is giving them what they want. While waiting in line, I overhear one woman tell another that she is offended by the fact that women often appear unclothed in movies and advertisements, while men rarely do. During a discussion about this paper, a close friend reports that she was surprised and saddened to visit her childhood home and find some New Year's resolutions she had made during her grade school years. As the years went by, the first item on each list never varied: "Lose 10 pounds . Lose weight . Lose 5 pounds ...... These stories and countless others form pieces of a larger mo- saic - one that shows how women are harmed and degraded by advertising images and other media messages. -

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická Fakulta

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakulta Katedra asijských studií Estetické vnímání krásy ženy v Japonsku Aesthetic perception of woman´s beauty in Japan Bakalářská diplomová práce Autor práce: Pomklová Lucie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Sylva Martinásková - ASJ Olomouc 2013 Kopie zadání diplomové práce Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla veškeré použité prameny a literaturu V Olomouci dne _______________________ Poděkování: Na tomto místě bych chtěla velice poděkovat Mgr. Sylvě Martináskové za konzultace, ochotu, flexibilitu při řešení jakýchkoliv problémů a odborné vedení mé práce. Díky jejím cenným radám a podnětům mohla tato práce vzniknout. Ediční poznámka Ve své práci používám anglický přepis japonských názvů společně se znaky nebo slabičnou abecedou, které budu užívat u ér, období, uvedených japonských termínů a jmen osob. Japonská jména uvádím v japonském pořadí čili první příjmení a za ním teprve následuje jméno osobní, ženská jména jsou uvedena v nepřechýlené podobě. Pro obecně známá místní jména či termíny, u kterých je český přepis již pevně stanoven pravidly českého pravopisu, používám tento do češtiny přejatý tvar. Kurzívu budu používat pro méně známé termíny, názvy ér a období a také pro citace. Používám citační normu ISO 690. Obsah 1 Úvod ................................................................................................................................... 8 2 Protohistorické období .................................................................................................. -

Marr, Kathryn Masters Thesis.Pdf (4.212Mb)

MIRRORS OF MODERNITY, REPOSITORIES OF TRADITION: CONCEPTIONS OF JAPANESE FEMININE BEAUTY FROM THE SEVENTEENTH TO THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Japanese at the University of Canterbury by Kathryn Rebecca Marr University of Canterbury 2015 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ·········································································· 1 Abstract ························································································· 2 Notes to the Text ·············································································· 3 List of Images·················································································· 4 Introduction ···················································································· 10 Literature Review ······································································ 13 Chapter One Tokugawa Period Conceptions of Japanese Feminine Beauty ························· 18 Eyes ······················································································ 20 Eyebrows ················································································ 23 Nose ······················································································ 26 Mouth ···················································································· 28 Skin ······················································································· 34 Physique ················································································· -

Or the Rhetoric of Medical English in Advertising Ibérica, Núm

Ibérica ISSN: 1139-7241 [email protected] Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos España Díez Arroyo, Marisa ‘Ageing youthfully’ or the rhetoric of medical English in advertising Ibérica, núm. 28, julio-diciembre, 2014, pp. 83-105 Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos Cádiz, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=287032049005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative 05 IBERICA 28.qxp:Iberica 13 22/09/14 19:22 Página 83 ‘Ageing youthfully’ or the rhetoric of medical English in advertising Marisa Díez Arroyo Universidad de Oviedo (Spain) [email protected] Abstract This study examines how cosmetics brands adopt characteristics of medical English in their web sites as a rhetorical strategy to persuade consumers. From the joint perspective of rhetoric, understood as persuasive stylistic choices, and a relevance-theoretic approach to pragmatics, the present paper explains how social assumptions about “ageing youthfully” are successfully strengthened in this type of advertising thanks to the alliance with medicine. This work explores various rhetorical devices, specified through both lexical and syntactic features. The analysis suggested here urges to reconsider research conclusions drawn on the use of science in advertising along truth-seeking premises, as well as previous classifications of this type of goods based on purely informative grounds. Keywords: medical English, cosmetics, web advertising, rhetoric, persuasion. Resumen “Envejecer manteniéndose joven” o la retórica del inglés médico en la publicidad Este trabajo analiza el uso del inglés médico en las páginas web de las marcas de cosméticos como recurso retórico para persuadir a los consumidores. -

Race, Gender, and Cosmetic Advertisements

RACE, GENDER, AND COSMETIC ADVERTISEMENTS “DARK SHADES DON’T SELL”: RACE, GENDER, AND COSMETIC ADVERTISEMENTS IN THE MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY UNITED STATES BY: SHAWNA COLLINS, B.A A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Shawna Collins, April 2018 ii McMaster University MASTER OF ARTS (2018) Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: “Dark Shades Don’t Sell”: Race, Gender, and Cosmetic Advertisements in the Mid- Twentieth Century United States AUTHOR: Shawna Collins, B.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Karen Balcom NUMBER OF PAGES: x, 160 iii Lay abstract My project analyzes skin bleaching and hair straightening advertisements appearing in four black-owned periodicals between 1920-1960: Chicago Defender, Afro-American, Plaindealer, and Ebony. The main goal has been to document the advertising messages about blackness and beauty communicated to black women through the advertisements of black-owned and white-owned cosmetic companies. I explore the larger racial and social hierarchies these advertising images and messages maintained or destabilized. A major finding of this project has been that advertising messages usually, but not always, diverged along racial lines. White-owned companies were more likely to use denigrating language to describe black hair and skin, and more likely to measure the beauty of black women based on how closely they approximated whiteness. Black-owned companies tended to challenge this ideology. They used messages about racial uplift as part of this challenge. iv Abstract In this study I examine the two major cosmetic categories - products for skin and products for hair - aimed at frican American women and advertised within the black press between 1920 and 1960. -

The Secrets of Traditional Asian Beauty

The Secrets of Traditional Asian Beauty - June 12, 2015 Asian Scientist Magazine | Science, Technology and Medicine News Updates From Asia - http://www.asianscientist.com The Secrets of Traditional Asian Beauty June 12, 2015 http://www.asianscientist.com/2015/06/print/secrets-traditional-asian-beauty/ AsianScientist (Jun. 12, 2015) - Did you know that many beauty products have their basis in science? We take a look at ancient natural beauty remedies that Asian women have been using for centuries. ------ #1 SKIN WHITENING Although Chinese notions of beauty have changed over its long history, one thing that has stayed constant is the desire for fair skin. Today, skin whitening products represent a multi-million dollar growth industry not only in China but all across Asia. In 2011, Taiwanese scientists found that compounds isolated from an herb used in traditional Chinese medicine could also be used to lighten skin. They showed that linderanolide B and subamolide A from the Cinnamomum subavenium plant could inhibit the production of melanin, the dark pigment that gives skin its color. When they tested the compounds on zebrafish embryos, which normally contain a highly visible band of black pigment, they found that exposure to a low dose of the compounds was sufficient to turn the embryos white. 1 / 11 The Secrets of Traditional Asian Beauty - June 12, 2015 Asian Scientist Magazine | Science, Technology and Medicine News Updates From Asia - http://www.asianscientist.com Photo: Shutterstock. ——— Cover photo: Shutterstock. #2 LIPSTICKS The Chinese were one of the first to redden their lips, using a lip balm made with the pigment vermilion. -

Luxury Fashion Advertising: Transitioning in the Age of Digital Marketing

LUXURY FASHION ADVERTISING: TRANSITIONING IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL MARKETING by Natasha Lamoureux B.A. Commerce, University of Ottawa, 2011 A Major Research Project presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Program of Fashion Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2014 © Natasha Lamoureux 2014 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this MRP. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract LUXURY FASHION ADVERTISING: TRANSITIONING IN THE AGE OF DIGITAL MARKETING Many luxury retailers fear embracing digital touchpoints, believing it could diminish a brand’s integrity. This study explored luxury fashion brands’ transition from traditional marketing strategies into the current “digital age” and experiential economy. The research encompassed a 2-phase qualitative content analysis: Phase 1 used an inductive approach that analyzed and categorized print advertisement images from Vogue US 1980 and 2013 into 3 major categories— types of product or service, overall presentation, and overall appearance of digital content. Phase 2 consisted of a deductive approach that examined Chanel’s and Burberry’s online and social touchpoints. -

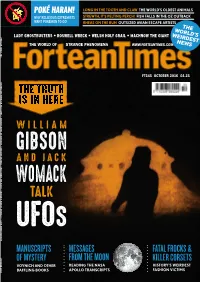

Womack and Gibson the Truth Is in Here

POKÉ HARAM! LONG IN THE TOOTH AND CLAW THE WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS WHY RELIGIOUS EXTREMISTS STREWTH, IT'S PELTING PERCH! FISH FALLS IN THE OZ OUTBACK WANT POKÉMON TO GO! RHEAS ON THE RUN OUTSIZED AVIAN ESCAPE ARTISTS THE WOR THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA LD’S LADY GHOSTBUSTERS • ROSWELL WRECK • WELSH HOLY GRAIL • MACHNOWWWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM THE GIANT WEIRDES FORTEAN TIMES 345 NEWS T THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA WWW.FORTEANTIMES.COM FT345 OCTOBER 2016 £4.25 GIBSON AND WOMACK TALK UFOS • MANUSCRIPTS OF MYSTERY • THE TRUTH IS IN HERE WILLIAM FA GIBSON SHION VICTIMS • MACHNOW THE GIANT • WORLD'S OLDEST ANIMALS • LADY GHOSTBUSTERS AND JACK WOMACK TALK UFOS MANUSCRIPTS MESSAGES FATALFROCKS& OCTOBER 2016 OFMYSTERY FROMTHEMOON KILLERCORSETS VOYNICH AND OTHER READING THE NASA HISTORY'S WEIRDEST BAFFLING BOOKS APOLLO TRANSCRIPTS FASHION VICTIMS LISTEN IT JUST MIGHT CHANGE YOUR LIFE LIVE | CATCH UP | ON DEMAND Fortean Times 345 strange days Pokémon versus religion, world’s oldest creatures, fate of Flight MH370, rheas on the run, Bedfordshire big cat, female ghostbusters, Australian fi sh fall, Apollo transcripts, avian CONTENTS drones, pornographer’s papyrus – and much more. 05 THE CONSPIRASPHERE 23 MYTHCONCEPTIONS 14 ARCHAEOLOGY 25 ALIEN ZOO the world of strange phenomena 15 CLASSICAL CORNER 28 NECROLOG 16 SCIENCE 29 FAIRIES & FORTEANA 18 GHOSTWATCH 30 THE UFO FILES features COVER STORY 32 FROM OUTER SPACE TO YOU JACK WOMACK has been assembling his collection of UFO-related books for half a century, gradually building up a visual and cultural history of the saucer age. Fellow writer and fortean WILLIAM GIBSON joined him to celebrate a shared obsession with pulp ufology, printed forteana and the search for an all too human truth.. -

The Impact of Corporate Ethical Behavior on Consumers in the Beauty Industry

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Honors Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2017 Making a Difference: the Impact of Corporate Ethical Behavior on Consumers in the Beauty Industry Paige M. Gould University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/honors Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, and the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Gould, Paige M., "Making a Difference: the Impact of Corporate Ethical Behavior on Consumers in the Beauty Industry" (2017). Honors Theses and Capstones. 356. https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/356 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFLUENCE OF ETHICAL BEHAVIOR 0 2017 Making a Difference: the Impact of Corporate Ethical Behavior on Consumers in the Beauty Industry Honors Thesis submitted to the Peter T. Paul College of Business and Economics University of New Hampshire Paige M. Gould Thesis Advisor: Bruce E. Pfeiffer, Ph.D. INFLUENCE OF ETHICAL BEHAVIOR 1 Abstract Over the years, the cosmetic industry has struggled with a variety of ethical issues. This research examines the effects of these unethical practices on consumers’ perceptions and judgements. More specifically, do consumers consider ethical issues when evaluating cosmetics? Can consumers’ ethical perceptions and decision making be influenced? If so, are heuristic appeals or systematic appeals more persuasive? The results of this study indicate that unless prompted, most consumers do not consider ethical issues when purchasing cosmetics. -

REGISTRATION DOCUMENT / L'oréal 2017 PROSPECTS by Jean-Paul Agon, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer

2017 Registration Document Annual Financial Report - Integrated Report WorldReginfo - dfc8fd1b-2e3e-449f-bd8b-d11113ade13a Content PRESENTATION OF THE GROUP 2017 PARENT COMPANY FINANCIAL 1 INTEGRATED REPORT 5 5 STATEMENTS* 285 1.1. The L’Oréal Group: fundamentals 6 5.1. Compared income statements 286 1.2. A clear strategy : Beauty for all 11 5.2. Compared balance sheets 287 1.3. Good growth momentum for shared, lasting 5.3. Changes in shareholders’ equity 288 development* 25 5.4. Statements of cash flows 289 1.4. An organisation that serves the Group’s development 40 5.5. Notes to the parent company financial statements 290 1.5. Internal Control and risk management system 44 5.6. Other information relating to the financial statements of L’Oréal parent company 309 5.7. Five-year financial summary 310 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE * 45 5.8. Investments (main changes including shareholding 2 threshold changes) 311 2.1. Framework for the implementation of corporate 5.9. Statutory Auditors' Report on the financial statements 312 governance principles 46 2.2. Composition of the Board of Directors 49 2.3. Organisation and modus operandi of the Board of Directors 66 STOCK MARKET INFORMATION 2.4. Remuneration of the members of the Board of Directors 84 6 SHARE CAPITAL 317 2.5. Remuneration of the executive officers 86 6.1. Information relating to the Company 318 2.6. Summary statement of trading by executive officers in 6.2. Information concerning the share capital* 320 L’Oréal shares in 2017 103 6.3. Shareholder structure* 323 2.7. Summary table of the recommendations of the AFEP-MEDEF Code which have not been applied 104 6.4.