Introduction Systematic Field Investigations Carried out in the Field of Archaeology During Recent Decades Have Thrown Fresh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fma-Special-Edition-Balisong.Pdf

Publisher Steven K. Dowd Contributing Writers Leslie Buck Stacey K. Sawa, a.k.a. ZENGHOST Chuck Gollnick Contents From the Publishers Desk History A Blade is Born Introduction to the Balisong Modern Custom Balisong Knives Balisong Master Nilo Limpin Balisong Information Centers Filipino Martial Arts Digest is published and distributed by: FMAdigest 1297 Eider Circle Fallon, Nevada 89406 Visit us on the World Wide Web: www.fmadigest.com The FMAdigest is published quarterly. Each issue features practitioners of martial arts and other internal arts of the Philippines. Other features include historical, theoretical and technical articles; reflections, Filipino martial arts, healing arts and other related subjects. The ideas and opinions expressed in this digest are those of the authors or instructors being interviewed and are not necessarily the views of the publisher or editor. We solicit comments and/or suggestions. Articles are also welcome. The authors and publisher of this digest are not responsible for any injury, which may result from following the instructions contained in the digest. Before embarking on any of the physical activates described in the digest, the reader should consult his or her physician for advice regarding their individual suitability for performing such activity. From the Publishers Desk Kumusta I personally have been intrigued with the Balisong ever since first visiting the Philippines in the early 70’s. I have seen some Masters of the balisong do very amazing things with the balisong. And have a small collection that I obtained through the years while being in the Philippines. In this Special Edition on the Balisong, Chuck Gollnick, Stacey K. -

Mobility and Subsistence Strategies: a Case Study of Inamgaon) a Chalcolithic Site in Western India

Mobility and Subsistence Strategies: A Case Study of Inamgaon) A Chalcolithic Site in Western India SHEENA PANJA ARCHAEOLOGY TODAY deals with being critical of our assumptions; being re flexive, relational, and contextual. The conclusions are always flexible and open to change as new relations emerge. It is impossible to approach the data without prejudice and without some general theory, but the aim is to evaluate such gen erality in relation to the contextual data. Our own understanding about human behavior acts as a generalization with which to understand the past. Nevertheless, we can agree that the past is objectively organized in contexts that are different from our own. The internal archaeological evidence then forces us to consider whether the past subject we are dealing with is familiar to us or makes us rethink deep-seated presuppositions about the nature of human behavior. The objective component of archaeological data means that the archaeologist can be confronted with a past that is different from the present. It is this guarded objectivity of the material "other" that provides the basis of critique. It is thus a hermeneutical pro cedure that involves a dialectical interplay between our own understandings and the forms of life we are seeking to understand. It is an ongoing dialogue between the past and the present in which the outcome resides wholly in neither side but is a product of both (Hodder 1991; Hodder et al. 1995; Wylie 1989). It is with these ideas in mind that this article is aimed to analyze critically certain categories archaeologists use to understand human behavior in a dialectical effort to understand the past. -

April Newsletter 2013.Cdr

KNIFEOKCA 38th Annual SHOW • April 13-14 Lane Events Center EXHIBIT HALL • Eugene, Oregon April 2013 Our international membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” YOU ARE INVITED TO THE OKCA 38th ANNUAL KNIFE SHOW & SALE April 13 - 14 * Lane Events Center & Fairgrounds, Eugene, Oregon In the super large EXHIBIT HALL. Now 360 Tables! ELCOME to the Oregon Knife have a Balisong/Butterfly knife Tournament, Auction Saturday only. Just like eBay but Collectors Association Special Blade Forging, Flint Knapping, quality real and live. Anyone can enter to bid in the WShow Knewslettter. On Saturday, Kitchen Cutlery seminar, Martial Arts, Silent Auction. See the display cases at the April 13, and Sunday, April 14, we want to Scrimshaw, Self Defense, Sharpening Club table to make a bid on some extra welcome you and your friends and family to the Knives, Wood Carving and a special seminar special knives . famous and spectacular OREGON KNIFE on “What do you do with that kitchen knife SHOW & SALE. Now the Largest you have.” And don't miss the FREE knife Along the side walls, we will have twenty organizational Knife Show East & West of the identification and appraisal by Tommy Clark four MUSEUM QUALITY KNIFE AND Mississippi River. from Marion, VA(Table N01) - Mark Zalesky CUTLERY COLLECTIONS ON DISPLAY from Knoxville TN (Table N02) - Mike for your enjoyment and education, in The OREGON KNIFE SHOW happens just Silvey on military knives is from Pollock addition to our hundreds of tables of hand- once a year, at the Lane Events Center Pines CA (Table J14) and Sheldon made, factory and antique knives for sale. -

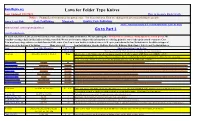

Laws for Folder Type Knives Go to Part 1

KnifeRights.org Laws for Folder Type Knives Last Updated 1/12/2021 How to measure blade length. Notice: Finding Local Ordinances has gotten easier. Try these four sites. They are adding local government listing frequently. Amer. Legal Pub. Code Publlishing Municode Quality Code Publishing AKTI American Knife & Tool Institute Knife Laws by State Admins E-Mail: [email protected] Go to Part 1 https://handgunlaw.us In many states Knife Laws are not well defined. Some states say very little about knives. We have put together information on carrying a folding type knife in your pocket. We consider carrying a knife in this fashion as being concealed. We are not attorneys and post this information as a starting point for you to take up the search even more. Case Law may have a huge influence on knife laws in all the states. Case Law is even harder to find references to. It up to you to know the law. Definitions for the different types of knives are at the bottom of the listing. Many states still ban Switchblades, Gravity, Ballistic, Butterfly, Balisong, Dirk, Gimlet, Stiletto and Toothpick Knives. State Law Title/Chapt/Sec Legal Yes/No Short description from the law. Folder/Length Wording edited to fit. Click on state or city name for more information Montana 45-8-316, 45-8-317, 45-8-3 None Effective Oct. 1, 2017 Knife concealed no longer considered a deadly weapon per MT Statue as per HB251 (2017) Local governments may not enact or enforce an ordinance, rule, or regulation that restricts or prohibits the ownership, use, possession or sale of any type of knife that is not specifically prohibited by state law. -

A Guide to Switchblades, Dirks and Daggers Second Edition December, 2015

A Guide to Switchblades, Dirks and Daggers Second Edition December, 2015 How to tell if a knife is “illegal.” An analysis of current California knife laws. By: This article is available online at: http://bit.ly/knifeguide I. Introduction California has a variety of criminal laws designed to restrict the possession of knives. This guide has two goals: • Explain the current California knife laws using plain language. • Help individuals identify whether a knife is or is not “illegal.” This information is presented as a brief synopsis of the law and not as legal advice. Use of the guide does not create a lawyer/client relationship. Laws are interpreted differently by enforcement officers, prosecuting attorneys, and judges. Dmitry Stadlin suggests that you consult legal counsel for guidance. Page 1 A Guide to Switchblades, Dirks and Daggers II. Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................... 1 II. Table of Contents ............................................................................ 2 III. Table of Authorities ....................................................................... 4 IV. About the Author .......................................................................... 5 A. Qualifications to Write On This Subject ............................................ 5 B. Contact Information ...................................................................... 7 V. About the Second Edition ................................................................. 8 A. Impact -

Subsistence Strategies and Burial Rituals: Social Practices in the Late Deccan Chalcolithic

Subsistence Strategies and Burial Rituals: Social Practices in the Late Deccan Chalcolithic TERESA P. RACZEK IN THE SECOND MILLENNIUM B.C., THE RESIDENTS OF THE WESTERN DECCAN region of India practiced an agropastoral lifestyle and buried their infant children in ceramic urns below their house floors. With the coming of the first millennium B.C., the inhabitants of the site of Inamgaon altered their subsistence practices to incorporate more wild meat and fewer grains into their diet. Although daily practices in the form of food procurement changed, infant burial practices remained constant from the Early Jorwe (1400 B.c.-lOOO B.C.) to the Late Jorwe (1000 B.c.-700 B.C.) period. Examining interments together with subsistence strategies firmly situates ideational practices within the fabric of daily life. This paper will explore the relationship between change and continuity in burial and subsistence practices around 1000 B.C. at the previously excavated Cha1colithic site of Inamgaon in the western Deccan (Fig. 1). By considering the act of burial as a moment of social construction that both creates and reflects larger traditions, it is possible to understand how each individual interment affects chronological variability. That burial traditions at Inamgaon were continuously recreated in the face of a changing society suggests that meaningful and significant practices were actively upheld. Burial practices at Inamgaon were both structured and fluid enough to allow room for individual and group expression. The con temporaneous variability that occurs in the burial record at Inamgaon may reflect the marking of various aspects of personhood. Burial traditions and the ability and desire of the living to conforITl to them vary over time and it is important to consider the specific social context in which they occur. -

ANNEXURE H-2 Notice for Appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships Indian Oil Corporation Limited Proposes to Appo

ANNEXURE H-2 Notice for appointment of Regular / Rural Retail Outlet Dealerships Indian Oil Corporation Limited proposes to appoint Retail Outlet dealers in Maharashtra, as per following details: SL No Name of location Revenue Type of RO Estimated Category Type of Minimum Dimension (in Finance to be Mode of Fixed Securit District monthly Site* M.)/Area of the site (in Sq. M.). arranged by Selection Fee / y Sales * the applicant Minimu Deposi Potential # m Bid t amount 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9a 9b 10 11 12 Regular / MS+HSD in SC CC / DC / Frontage Depth Area Estim Estimat Draw of Rural Kls CFS ated ed fund Lots / work require Bidding SC CC-1 ing d for SC CC-2 capit develo SC PH al pment ST requi of ST CC-1 reme infrastru ST CC-2 nt for cture at ST PH oper RO OBC ation OBC CC-1 of RO OBC CC-2 OBC PH OPEN OPEN CC-1 OPEN CC-2 OPEN PH 1 Neral on Karjat-Neral Road Regular 200 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of 0 3 lots Raigad 2 On Pali Vikramgarh Road Regular 190 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of 0 3 Thane lots 3 Thal to Mandve Regular 150 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of 0 3 Raigad lots 4 Palghar char rasta to Umroli on Boisar Road Regular 250 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of 0 3 Palghar lots 5 Within 10 kms from Saikheda, on Karanjgaon to Regular 120 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of 0 3 Nandurmadmeshwar Road Nashik lots 6 WITHIN 10 KMS FROM MANMAD TOWARDS Regular 100 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of 0 3 NANDGAON ON SH-25 Nashik lots 7 SATURLI ON GHOTI -TRAMBAK ROAD SH-29 Regular 150 SC CFS 30 30 900 0 0 Draw of 0 3 Nashik lots 8 On NH-548A (Karjat-Murbad Road) from Karjat -

OKCA 29Th Annual • April 17-18

KNIFEOKCA 29th Annual SHOW • April 17-18 Lane County Fairgrounds & Convention Center • Eugene, Oregon April 2004 Ourinternational membership is happily involved with “Anything that goes ‘cut’!” YOU ARE INVITEDTO THE OKCA 29th ANNUAL KNIFE SHOW & SALE In the freshly refurbished EXHIBIT HALL. Now 470 Tables! You Could Win... a new Brand Name knife or other valuable prize, just for filling out a door prize coupon. Do it now so you don't forget! You can also... buy tickets in our Saturday (only) RAFFLE for chances to WIN even more fabulous knife prizes. Stop at the OKCA table before 5:00 p.m Saturday. Tickets are only $1 each, or 6 for $5. Free Identification & Appraisal Ask for Bernard Levine, author of Levine's Guide to Knives and Their Values, at table N-01. ELCOME to the Oregon Knife At the Show, don't miss the special live your name to be posted near the prize showcases Collectors Association Special Show demonstrations Saturday and Sunday. This (if you miss the posting, we will MAIL your WKnewslettter. On Saturday, April 17 year we have Martial Arts, Scrimshaw, prize). and Sunday, April 18, we want to welcome you Engraving, Knife Sharpening, Blade Grinding and your friends and family to the famous and Competition, Knife Performance Testing and Along the side walls, we will have more than a spectacular OREGON KNIFE SHOW & SALE. Flint Knapping. New this year: big screen live score of MUSEUM QUALITY KNIFE AND Now the Largest Knife Show in the World! TV close-ups of the craftsmen at work. And SWORD COLLECTIONS ON DISPLAY for don't miss the FREE knife identification and your enjoyment, in addition to our hundreds of The OREGON KNIFE SHOW happens just appraisal by renowned knife author tables of hand-made, factory, and antique knives once a year, at the Lane County Fairgrounds & BERNARD LEVINE (Table N-01). -

The Lure of the Balisong Some Weapons Experts Say the Balisong Or Butterfly Knife Opens Faster Than a Switchblade

Lye’s law The Lure of the Balisong Some weapons experts say the balisong or butterfly knife opens faster than a switchblade. It certainly makes a great impression when twirled in the hand and opening and closing the blade with each resolution. But is it practical, or legal? By William Lye he balisong is a beautifully made knife, and thus portrays a bad image. In many those mishaps! especially those produced by the well- states of the USA it is illegal to own, However, the balisong is probably the Tknown US knife maker, Benchmade. possess or carry a balisong except in the last knife most would choose for self- However, in most states and territories of state of Oregon (the home of Benchmade). In defence. Its use relies too much on fine Australia, the balisong is a prohibited some parts of Europe and Asia, the balisong motor skills. Its fancy and sometimes aerial weapon. Most states (except WA and ACT) is legally and readily available for purchase. artistic motion might leave some people in refer to it as the butterfly knife (presumably The balisong is most likely banned awe of the balisong, but I would certainly be more worried facing a competent knifer with Balisongs: prohibited weapons in Australia. a kitchen knife than a person with a balisong capable of doing only fancy twirls! In a stressful situation, the last thing one would be thinking about is how to flail the balisong. It is indeed very tricky to deploy properly. In Australia, there is no good reason for anyone to own or carry a balisong other than to train in one’s martial arts style. -

2 0 1 8 Catalog

LifeSharp is more than a lifetime guarantee. It’s a creed to live by. It’s the ever-evolving pursuit of excellence. A never-ending journey to master your craft, hone your skills and soak up some wisdom along the way. At Benchmade, every knife we make is a learning experience. We strive to make each knife better than the knife that came before it, as we chase the elusive perfection. And, once that knife passes from our hands to yours, we’ll ensure that your Benchmade stays in pristine condition for many generations to come. Our word is our bond and we’ll hold up our end keeping your knife sharp, but, it’s up to you to keep your LifeSharp. 2018 CATALOG HOW TO CHOOSE YOUR BENCHMADE KNIFE ACTIVITY BLADE STYLE Outdoor, tactical, every day use—there are many uses for a knife, and some While the cutting edge does the work, the edge is applied to the cutting surface knives are better for certain activities than others. in different ways depending on the shape of the blade. Blade shapes with larger BMK ICONOGRAPHY radiuses may be optimal for hunting, while blade shapes with hard angles, like the tanto, may be better for tactical applications. BMKHOW ICONOG WILLRAPHY YOU USE YOUR KEY KNIFE FEATURES BMK ICONOGRAPHYKNIFE? SHAPES AXIS® Exclusive to TACTICAL Designed for hard, immediate Benchmade,AXIS® The AXIS® the AXIS® lock is lock truly Clip-point Blade contains a sharp Sheepsfoot The spine of the use,BMK these ICONOG high-strengthRAPHY knives feature isambidextrous truly ambidextrous and extremely and beak, typically forward of the blade ‘rolls’ into the tip, creating a robust mechanisms for situations where extremelystrong. -

Pincode Officename Mumbai G.P.O. Bazargate S.O M.P.T. S.O Stock

pincode officename districtname statename 400001 Mumbai G.P.O. Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Bazargate S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 M.P.T. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Stock Exchange S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Tajmahal S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400001 Town Hall S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Kalbadevi H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 S. C. Court S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400002 Thakurdwar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 B.P.Lane S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Mandvi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Masjid S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400003 Null Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Ambewadi S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Charni Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Chaupati S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Girgaon S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Madhavbaug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400004 Opera House S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba Bazar S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Asvini S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Colaba S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 Holiday Camp S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400005 V.W.T.C. S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400006 Malabar Hill S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Bharat Nagar S.O (Mumbai) Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 S V Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Grant Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 N.S.Patkar Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400007 Tardeo S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Mumbai Central H.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 J.J.Hospital S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Kamathipura S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 Falkland Road S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400008 M A Marg S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Noor Baug S.O Mumbai MAHARASHTRA 400009 Chinchbunder S.O -

Semantic Specificity of Perception Verbs in Maniq

Semantic specificity of perception verbs in Maniq © Ewelina Wnuk 2016 Printed and bound by Ipskamp Drukkers Cover photo: A Maniq campsite, Satun province, Thailand, September 2011 Photograph by Krittanon Thotsagool Semantic specificity of perception verbs in Maniq Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op vrijdag 16 september 2016 om 10.30 uur precies door Ewelina Wnuk geboren op 28 juli 1984 te Leżajsk, Polen Promotoren Prof. dr. A. Majid Prof. dr. S.C. Levinson Copromotor Dr. N. Burenhult (Lund University, Zweden) Manuscriptcommissie Prof. dr. P.C. Muysken Prof. dr. N. Evans (Australian National University, Canberra, Australië) Dr. N. Kruspe (Lund University, Zweden) The research reported in this thesis was supported by the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, München, Germany. For my parents, Zofia and Stanisław Contents Acknowledgments ............................................................................................. i Abbreviations ................................................................................................ vii 1 General introduction ........................................................................................ 1 1.1 Aim and scope ................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Theoretical background to verbal semantic specificity