Appointments, Pay and Performance in UK Boardrooms by Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annu Al Repor T

2019 CELEBRATING25 YEARS ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL We Move People Letter from our leadership BOARD OF DIRECTORS Amberley Baker Friends of Pathways supports a vibrant community by promoting Dear Friends, Co-President Today Jackson boasts 130 miles of well-maintained sustainable transportation and healthy recreation in Jackson Hole. I love working for an organization empowered by backyard trails that welcome thousands of people a day Julie O’Halloran people united in their joy for getting outside and moving pursuing many different activities while respecting the Co-President around Jackson Hole in the sun, wind and fresh air. natural and wild resources that we all care about. Friends of Pathways celebrated its 25th year in 2019 Frank Brummer Secretary - 25 years of working to connect Jackson Hole through a Thanks to YOU – your dreaming, your demanding, your network of well-built trails and safe pathways. For many dollars – our pathways and trails are now well-used and John Hechinger of us who enjoy and rely on the trails and pathways, it well-loved assets that wind through our beautiful home. Treasurer would be hard to imagine life in Jackson Hole without Your collective energy and investments have been the them. But the fact is, 25 years ago, people had very few catalyst for transforming ambitious ideas into reality. Don Gervais sustainable choices for getting to work, to school or to Jim Hunt play, without first getting in the car. But there is still much work to do to make Jackson a Amy Puccia place where walking, biking and car-free travel are the Jeff Rice Twenty-five years ago there wasn’t a single mile of most desired and convenient modes to get around. -

Leslie, My Name Is Evil

E1 Entertainment presents A New Real Films Production A Masculine‐Feminine Film Leslie, My Name Is Evil Directed by Reginald Harkema Producers: Jennifer Jonas and Leonard Farlinger An Official Selection of the 2009 Toronto International Film Festival, Vanguard Section www.lesliemynameisevil.com TIFF US Press Contact: Producer Contact: mPRm Public Relations New Real Films Inc. Alice Zou, [email protected] 669 Shaw St. Toronto Inter‐Continental Hotel Toronto, ON 220 Bloor Street West, Suite 325 M6G 3L8 Ph: 416‐960‐5200 Office: 416‐536‐1696 Cell 213‐359‐5775 [email protected] SYNOPSIS As the ‘60s rolled to a close, the United States was at the threshold of a turbulent time in history. President Nixon was in the White House and the U.S. was at war in Vietnam. The image of the picture‐perfect, stay‐at‐home housewife with the ideal husband and family was being threatened. Forces of change—a sexual revolution, the use of hallucinogenic drugs and a new founded challenge to authority—had crept into family rooms and dinning table conversations. Raised in a traditional Christian family, Perry leads a sheltered life, always doing what is expected of him. He has a wonderful virgin Christian girlfriend, Dorothy. He attends church with his family on Sundays and enjoys family dinners. He is following a career path that will prevent him from being drafted to fight in Vietnam. As a chemist he is book smart and company driven, but doesn’t know the harsh realities of the world. Everything he believes in is challenged the day he is chosen to be a jury member in a hippie death cult murder trial, where the defendant on trial is a strikingly beautiful woman named Leslie. -

Movie Data Analysis.Pdf

FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM COGS108 Final Project Group Members: Yanyi Wang Ziwen Zeng Lingfei Lu Yuhan Wang Yuqing Deng Introduction and Background Movie revenue is one of the most important measure of good and bad movies. Revenue is also the most important and intuitionistic feedback to producers, directors and actors. Therefore it is worth for us to put effort on analyzing what factors correlate to revenue, so that producers, directors and actors know how to get higher revenue on next movie by focusing on most correlated factors. Our project focuses on anaylzing all kinds of factors that correlated to revenue, for example, genres, elements in the movie, popularity, release month, runtime, vote average, vote count on website and cast etc. After analysis, we can clearly know what are the crucial factors to a movie's revenue and our analysis can be used as a guide for people shooting movies who want to earn higher renveue for their next movie. They can focus on those most correlated factors, for example, shooting specific genre and hire some actors who have higher average revenue. Reasrch Question: Various factors blend together to create a high revenue for movie, but what are the most important aspect contribute to higher revenue? What aspects should people put more effort on and what factors should people focus on when they try to higher the revenue of a movie? http://localhost:8888/nbconvert/html/Desktop/MyProjects/Pr_085/FinalProject.ipynb?download=false Page 1 of 62 FinalProject 25/08/2018, 930 PM Hypothesis: We predict that the following factors contribute the most to movie revenue. -

Addendum to Surveyor's Report Dated 05/05/1997

•engiiwars • archXacts 0€ST Associates, Inc. •surveyors ^•1*^ . constnjction manageis 343 Gorham Road South Portland, ME 04106-2317 • TEL (207) 761 -1770 FAX (207) 774-1246 E-mail: [email protected] • Web Site; www.oest.com Ir, -. 259.01.03 :^~^J'.D RECORDS CTR TO: R.F. Weston, Inc. Federal Programs Division Burlington, Massachusetts FROM: Jerome B. Watts, P.L.S. SDMS DocID 4608 DATE: January 20,1998 SUBJECT: Addendum to Surveyor's Report dated May 5,1997 Eastem Surplus Superfund Site Meddybemps, Maine This addendum is intended to address the title opinion of Mr. Peter G. Rich, Esquire, of Portland, Maine, dated December 12, 1997 and clarify any concems written in a document by or for R.F. Weston under Task 1.5: Procurement of Additional Survey Work. ^i**' ITEM 1 — RF.CORD OWNER According to title opinion, Harry J. Smith, Jr. owns all land west of Denny's River, north ofthe old Route 191, east ofthe Lord's and south of Meddybemps Lake and the State of Maine. Harry J. Smith, Sr. appealed a notice of condemnation in 1966 and won a judgement in Superior Court Docket 1716 that the taking was to be voided. No record was found in the registry to substantiate the court case. See plan update enclosed and Book 1003, Page 228, Book 2132, Page 45. According to title opinion, Harry J. Smith, Jr. owns two-thirds interest and Dawn K. Smith owns one-third interest in all land east ofthe Denny's River, north ofthe old Route 191, west ofthe Orchard's, south ofthe Meddybemps Lake and State of Maine. -

HISTORIC PRESERVATION PLAN for NOME, ALASKA

Mayor Nome Planning Commission John K. Handeland Kenneth Hughes III, Chair Mathew Michels City Manager Sara Lizak Glen Steckman John Odden Deputy City Clerk Gregory Smith Susan Hite Carol Piscoya Colleen Deighton NOME PLANNING COMMISSION REGULAR MEETING AGENDA TUESDAY, MAY 04, 2021 at 7:00 PM COUNCIL CHAMBERS IN CITY HALL 102 Division St. ▪ P.O. Box 281 ● Nome, Alaska 99762 ● Phone (907) 443-6663 ● Fax (907) 443-5345 ROLL CALL APPROVAL OF AGENDA APPROVAL OF MINUTES A. 21-04-06 Nome Planning Commission Regular Meeting Minutes, PAGE 2 HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION ACTIVITIES A. Final Review of Preliminary Draft Historic Preservation Plan, PAGE 7 COMMUNICATIONS A. Letter of April 5, 2021 from Department of Transportation & Public Facilities to City of Nome re: 2021 Construction Season, PAGE 7 B. Email of April 5, 2021 from CRS Specialist James to City of Nome re: Annual CRS Certification, PAGE 85 CITIZENS' COMMENTS NEW BUSINESS A. Conditional Use Permit Application for Lot 6A Block 43A - 402 E N Street, PUBLIC HEARING, PAGE 88 B. Variance Application for Lot 5A Block 50 - 103 East King Place, PUBLIC HEARING, PAGE 101 C. R-2021-01 A Resolution Recommending the Nome Common Council Adopt the 2018 International Property Management Code, PAGE 105 D. R-2021-02 A Resolution in Support of Kawerak, Inc's Effort to Develop a Feasibility Study for a Regional Recycling Center That Would Serve the Residents and Visitors of the Bering Strait Region, PAGE 171 STAFF REPORTS Page 1 of 2 1 Nome Planning Commission Regular Meeting May 04, 2021 A. City Planner Report, PAGE 173 B. -

The Final Season

cSAsad Season 5 Synopses – The Final Season Everything seemed to be going great at the end of last season on SAVING HOPE. Dr. Alex Reid (Erica Durance) and Dr. Maggie Lin (Julia Taylor Ross) had won the prestigious fellowship award and Dr. Charlie Harris (Michael Shanks) had solved his spirit problem. But celebrations were cut short by a vengeful Tom Crenshaw (Travis Milne, ROOKIE BLUE) who appeared at the Hope Zion Hospital Fellowship Awards and fired a shot at Alex and Charlie. The fifth and final season of SAVING HOPE sees the Hope Zion Hospital staff thrust into turmoil. As we pick up in the aftermath of the heart- stopping cliffhanger, the doctors of Hope Zion are in a state of self-doubt. As Alex grapples with her destiny and faces a big decision, her fellow doctors deal with new challenges as changes come to Hope Zion, including a new CEO, that will not only affect the livelihood of the hospital, but also its doctors and everything they hold dear. And Charlie, thinking his surgery had exorcised his spirits, realizes that the ghosts aren’t going away anytime soon. SAVING HOPE stars Canadian Screen Award nominee Erica Durance (SMALLVILLE) as Dr. Alex Reid; Michael Shanks (STARGATE SG-1) as Dr. Charlie Harris; Canadian Screen Award-winner and 2016 Earle Grey Award recipient Wendy Crewson (Room) as Dr. Dana Kinney; Benjamin Ayres (BITTEN) as Dr. Zach Miller; Canadian Screen Award nominee Julia Taylor Ross (GOTHAM) as Dr. Maggie Lin; Canadian Screen Award- winner Michelle Nolden (Prisoner X) as Dr. Dawn Bell; Huse Madhavji (CALL ME FITZ) as Dr. -

Vol. 23 Num. 1 the FARMS Review

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 23 Number 1 Article 17 2011 Vol. 23 Num. 1 The FARMS Review Mormon Studies Review Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Review, Mormon Studies (2011) "Vol. 23 Num. 1 The FARMS Review," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 23 : No. 1 , Article 17. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol23/iss1/17 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. BX 8622 . R325x vol.23 n o.1 MORMON STUDIES revzew--·- VOLUME 23 • NUMBER 1 • 2011 Highlights Neal A. Maxwell Lecture I The Book of Mormon: Passport to Discipleship 1 BY MARILYN ARNOLD Revisiting "A Key for Evaluating Nephite Geographies" 13 BY JOHN E. CLARK Shattered Glass: The Traditions of Mormon Same-Sex Marriage Advocates Encounter Boyd K. Packer 61 BY GREGORY L. SMITH Examining a Misapplication of Nearest Shrunken Centroid Classification to Investigate Book of Mormon Authorship BY PAUL J. FIELDS, G. BRUCE SCHAALJE, AND MATTHEW ROPER Beyond Politics 135 BY HUGH NIBLEY volume 23, number 1 • 2011 MorMon StudieS review EDITOR PRODUCTION EDITOR Daniel C. Peterson Don L. Brugger ASSOCIATE EDITORS EDITORIAL INTERNS Louis C. Midgley Julie A. Davis George L. Mitton Stetson J. Robinson Gregory L. -

Chris Webb Stunt Coordinator / Stunt Performer / Stunt Actor

Chris Webb Stunt Coordinator / Stunt Performer / Stunt Actor Office: 604-299-7050 Cel: 604-727-6850 Website: www.stuntscanada.com Website: www.chriswebbstunts.com Website: www.practicalgravity.com Email: [email protected] UBCP Member#10295/ACTRA Member#V01-07165 Height: 6’2 Weight: 190 Hair: Brown Eyes: Blue Waist: 34 Inseam: 34 Hat: 7 5/8 Jacket: 44 Tall Shoe: 10 ½ Neck: 16 ½ ACTING SHOW ROLE DIRECTOR Debris Stunt Actor – “Scientist” Various A Million Little Things Actor – “Brandon” Nina Lopez-Corrado The Twilight Zone Actor – “Lenny” Ana Lily Amirpour Life XP – Level 9 Stunt Actor – “Laser Superhero” Trevor Addie Life XP – Level 7 Stunt Actor – “Western Fighter” Trevor Addie Life XP – Level 6 Stunt Actor – “Kaz-napper” Trevor Addie Charmed Actor – “Tartarus Guard” Stuart Gillard The Flash – Season 5 Actor – “David Hersh” Andi Armaganian The Flash – Season 4 Stunt Actor – “Armoured Car Driver” Gregory Smith The Flash – Season 2 Stunt Actor – “Criminal Driver” Armen V. Kevorkian The Flash – Season 1 Principal Actor – “Trusting Face Man” Wendey Stanzler Death Note Stunt Actor – “Military Contractor #1” Adam Wingard Mech-X4 Stunt Actor – “Head Guard” Adam B. Stein A Dog’s Purpose Actor - “Kidnapper” Lasse Hallström Travelers Actor - “Business Man” Andy Mikita There are Monsters Lead Creature Performer Bryan Bertino I, Zombie – Season 1 Stunt Actor – “Bicycle Cop” Michael Fields Motive – Season 4 Stunt Actor – “Jeremy Sheridan” Andy Mikita Motive – Season 2 Stunt Actor – “Alan” David Frazee The Leap (Short) Stunt Actor – “Red Merc” -

The Flash Season 5 Free Download Everything We Know About 'The Flash' Season 4

the flash season 5 free download Everything We Know About 'The Flash' Season 4. There’s no rest for the fastest man alive. After vanquishing Savitar in the Season 3 finale of The Flash , Barry Allen (Grant Gustin) gave himself to the Speed Force to prevent it from collapsing all over Central City. Sacrificing a life with his true love Iris West (Candice Patton) and leaving Wally West to become the new Flash, Season 4 will no doubt be different than even last year’s setup with the alternate Flashpoint timeline, which went by just a little too quickly. The Season 4 premiere of The Flash won’t arrive until the fall, but already there are hints and clues as to what S.T.A.R. Labs will look like upon the show’s return. Here are three things we know — and are confidently guessing — about The Flash Season 4. It Will Premiere This Fall. Season 4 of The Flash will premiere on Tuesday, October 10, at 8 p.m. Eastern. The CW made the announcement on June 8, along with the premiere dates for the three other Arrowverse shows, Supergirl , Legends of Tomorrow , and Arrow . Those shows will premiere on October 9, 10, and 12, respectively. Supergirl will also air at 8 p.m., while Arrow and Legends will start at 9 p.m., with Legends kicking off right after The Flash on Tuesdays. And We Have a Plot. Here’s the official synopsis from The CW: The Villain Isn’t a Speedster, and It Is Probably the Thinker. -

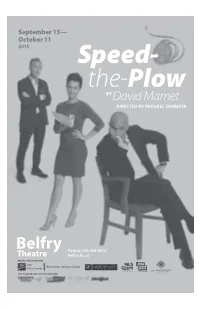

Speed- Plow The

Speed- t h e- Plow BY David Mamet DIRECTED BY MICHAEL SHAMATA Tickets 250 385 6815 belfry.bc.ca PRODUCTION SPONSORS 40TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON SPONSORS DV 2015-16 Ads.qxp_DV Ad 16-09 Belfry 2015-09-04 5:09 PM Page 1 Make it your own! DANCE VICTORIA’S POPULAR FLEX PASS IS BACK FOR THE 2015-16 SEASON! BALLET BC CONTEMPORARY BALLET SPECIAL 30TH ANNIVERSARY PRESENTATION NOVEMBER 13 + 14, 2015 BALLETS JAZZ DE MONTRÉAL CONTEMPORARY FEBRUARY 26 + 27, 2016 KIDD PIVOT + ELECTRIC COMPANY DANCE THEATRE BETROFFENHEIT MARCH 11 + 12, 2016 ROYAL WINNIPEG BALLET BALLET GOING HOME STAR – TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION APRIL 1 + 2, 2016 PLUS ALBERTA BALLET The Nutcracker CLASSICAL BALLET WITH THE VICTORIA SYMPHONY n a i d DECEMBER 4 – 6, 2015 o b o l S l e a h c i M MCPHERSON BOX OFFICE: Our Flex Pass gives you four tickets to use in © o any combination so you can choreograph t 250-386-6121 o h the season you want to see. P . r e y e M SEASON SPONSOR ANNUAL OPERATING GRANTS PROVIDED BY l e h c a R s ’ C Medical Laser + Skin Clinic B t e l Suite 101 – 1830 Oak Bay Ave. l a DermaSpa.ca B The Belfry Theatre presents Speed-the-Plow by David Mamet Brian Markinson Bobby Gould Vincent Gale Charlie Fox Celine Stubel Karen Director Michael Shamata Set and Costume Designer Shawn Kerwin Fossil Fuel Free InvestingLighting Designer Michael Whitfield Many people say that thereComposer is a performance and Sound penalty Designerfor Tobin Stokes aligning your investments with your values. -

CHRIS BANTING Director of Photography Chrisbanting.Com

CHRIS BANTING Director of Photography chrisbanting.com PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS SUPERGIRL Jesse Warn WARNER BROS. TV / CW DP: Season 6, 2 eps. Glen Winter Chris Pavoni, Jessica Queller 2nd Unit: Seasons 5–6 Robert Rovner, Greg Berlanti ARROW James Bamford WARNER BROS. TV / CW DP: Season 7, 3 eps. Gord Verheul Todd Pittson, Beth Schwartz Season 6, 2 eps. Gregory Smith Greg Berlanti MONSTER Nic Fairbrother 2MORO PRODUCTIONS Short Film Nic Fairbrother, Jean-Marc Moro 2BR02B: TO BE OR NAUGHT TO BE Marco Checa Garcia Artin John, Hannah Gordon Short Film Derek Ryan Pedersson THE SPIRAL Roberta McDonald DRAMA CLUB Short Film Melanie Jones CAMERA OPERATOR Partial List ELECTRA WOMAN AND DYNA GIRL Chris Marrs Piliero LEGENDARY TV Pilot Chris Foss, Tim Carter GRAVY James Roday SHOUT! FACTORY Feature Film Craig Chapman, Kerry Rock VENDETTA Jen & Sylvia Soska WWE / THE FILM ARCADE Feature Film Donald Munro, Michael Luisi THE ROMEO SECTION Chris Haddock CBC Pilot & Season 1 Anne Wheeler John Lenic, Arvi Liimatainen STOLEN DAUGHTER Jason Bourque LIFETIME TV MOW Matt Drake, Kirk Shaw OLYMPUS Martin Wood REUNION PICTURES / SYFY Pilot & Season 1 Amanda Tapping Tia Buhl, Michael O’Connor PERFECT HIGH Vanessa Parise SEPIA FILMS / LIFETIME TV MOW Ian R. Smith, Kim Roberts LIGHTHOUSE Vanessa Parise TLH PROD. / LIFETIME TV MOW Galen Fletcher, Lindsay Moffat PSYCH James Roday NBC / USA NETWORK Seasons 4–8 Gordon Mark, Steve Franks LONESOME DOVE CHURCH Terry Miles LIONSGATE Feature Film Jack Nasser KLONDIKE Simon Cellan Jones DISCOVERY CHANNEL Pilot Erin Smith, Ridley Scott END OF THE WORLD Steven Monroe SYFY MOW Rupert Harvey, Lisa Hansen NIGHT AT THE MUSEUM: Shawn Levy 20TH CENTURY FOX BATTLE OF THE SMITHSONIAN Chris Columbus Feature Film Michael Barnathan INNOVATIVE-PRODUCTION.COM | 310.656.5151 .