A Rule of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Act of Consecration to the Immaculate

COMFORTER OF THE AFFLICTED Pray for Us 0//icial cAct o/ Concecration OF THE DOMINICAN ORDER TO THE .!Jmmaculate J.leart o/ .Atarg QUEEN OF THE MOST HOLY ROSARY, Help of Christians, Refuge of the llUman race, Victress in all (I God's battles, we, suppliantly and with great confidence, not in our own merits but solely because of the immense goodness of thy motherly heart, prostrate ourselves before thy throne begging mercy, grace, and timely aid. To thee and to thy Immaculate Heart we bind and conse crate ourselves anew, in union with our Holy Mother, the 01Urch, the Mystical Body of Christ. Once again we proclaim thee the Queen of our Order-the Order truly, which thy son, Dominic, 240 Dominicana founded to preach, through thy aid, the word of truth everywhere for the salvation of souls; the Order which thou has chosen as a beautiful, fragrant, and splendid garden of delights; the Order in which the light of wisdom ought so splendidly to shine that its members might bestow on others the fruit of their contempla tion, not only by courageously uprooting heresy but also by sow ing the seeds of virtue everywhere; the Order which during the course of centuries has gloried in thy scapular and in thy most holy Rosary, which daily and in the hour of death devoutly and confidently salutes thee as advocate in those words most sublime: Hail Holy Queen, Mother of Mercy. To thee, 0 Mary, and to thy Immaculate Heart we conse crate today this religious house, this community, that thou might be truly its Queen; that perfect observance, the love of thy Son in the Most Holy Sacrament of the Altar, the love of thy praise, and the love of St. -

RUSSIAN TRADITION of the KNIGHTS of MALTA OSJ The

RUSSIAN TRADITION OF THE KNIGHTS OF MALTA OSJ The Russian tradition of the Knights Hospitaller is a collection of charitable organisations claiming continuity with the Russian Orthodox grand priory of the Order of Saint John. Their distinction emerged when the Mediterranean stronghold of Malta was captured by Napoleon in 1798 when he made his expedition to Egypt. As a ruse, Napoleon asked for safe harbor to resupply his ships, and then turned against his hosts once safely inside Valletta. Grand Master Ferdinand von Hompesch failed to anticipate or prepare for this threat, provided no effective leadership, and readily capitulated to Napoleon. This was a terrible affront to most of the Knights desiring to defend their stronghold and sovereignty. The Order continued to exist in a diminished form and negotiated with European governments for a return to power. The Emperor of Russia gave the largest number of Knights shelter in St Petersburg and this gave rise to the Russian tradition of the Knights Hospitaller and recognition within the Russian Imperial Orders. In gratitude the Knights declared Ferdinand von Hompesch deposed and Emperor Paul I was elected as the new Grand Master. Origin Blessed Gerard created the Order of St John of Jerusalem as a distinctive Order from the previous Benedictine establishment of Hospitallers (Госпитальеры). It provided medical care and protection for pilgrims visiting Jerusalem. After the success of the First Crusade, it became an independent monastic order, and then as circumstances demanded grafted on a military identity, to become an Order of knighthood. The Grand Priory of the Order moved to Rhodes in 1312, where it ruled as a sovereign power, then to Malta in 1530 as a sovereign/vassal power. -

Analysis of Constitution

ANALYSIS OF CONSTITUTION ARTICLE I Section 1 Name of Order Section 2 Name of Convent General Section 3. Name of Priory; of Knight ARTICLE II Section 1 Jurisdiction ARTICLE III Section 1 Membership Section 2 Representative must be member ARTICLE IV Section 1 Names and rank of officers ARTICLE V Section 1 Who eligible to office Section 2 Member or officer must be in good standing in Priory Section 3. Only one officer from a Priory Section 4 Officers selected at Annual Conclave Section 5 Officers must be installed Section 6 Officers must make declaration Section 7 Officers hold office until successors installed Section 8 Vacancies, how filled ARTICLE VI Section 1 Annual and special Conclaves Section 2 Quorum ARTICLE VII Section 1 Convent General has sole government of Priories Section 2 Powers to grant dispensation, and warrants, to revoke warrants Section 3. Power to prescribe ceremonies of Order Section 4 Power to require fees and dues Section 5 Disciplinary, for violation of laws ARTICLE VIII Section 1 Who shall preside at Convent General Section 2 Powers and duties of Grand Master-General Section 3. Convent General may constitute additional offices ARTICLE IX Section 1 Legislation, of what it consists Section 2 How Constitution may be altered Section 3. When Constitution in effect 4 CONSTITUTION ARTICLE I - Names Section 1 This Order shall be known as the Knights of the York Cross of Honour and designated by the initials “K.Y.C.H.” Section 2 The governing body shall be known as Convent General, Knights of the York Cross of Honour. -

PRINCETHORPE PRIORY by Fr Elphege Hind OSB Ampleforth Journal 11 (1905) Pp.192-204 © Ampleforth Abbey Trustees

PRINCETHORPE PRIORY by Fr Elphege Hind OSB Ampleforth Journal 11 (1905) pp.192-204 © Ampleforth Abbey Trustees he Benedictine nuns of Princethorpe were the first of the refugees from France to arriye in England and have been in this country for more than one hundred Tyears. They were not originally a community of English nuns living in exile abroad, like the communities of Stanbrook East Bergholt and many others of our Benedictine convents. They came to our shores at the time of the Revolution as exiles suffering for their fidelity to the Faith, and though their intention was not to remain, the kindly welcome they received in England dissuaded them from carrying out their original plan of seeking a home in Belgium. Their foundress was Mère Marie Granger, a saintly soul who had taken the habit of St. Benedict in the Abbey of Montmartre near Paris. It was quite contrary to her desires and inclinations that she ever came to be the foundress of a Benedictine monastery. It was mainly due to the work and persuasion of her brother that she consented to put her hand to so great a work. He was a canon of Paris, a notable ecclesiastic of the time, and one who saw in his sister’s character all the necessary qualities for a work of this kind. Accordingly, when the Abbey of Notre Dame des Isles in Burgundy was vacant, he tried to obtain it for his sister. The King gave his consent to the proposal. At first she held back and refused to leave Montmartre, but in the end gave her consent and went so far as to make her Profession of Faith before the Archdeacon of Paris. -

The Book of the Foundation of ST Bartholomew's Church

THE BOOK OF THE FOUNDATION OF ST BARTholomew’S CHURCH: CONSECRATION, RESTORATION, AND TRANSLATION Laura Varnam So al these thyngis that bene seide or shall be seide / they beholde the ende / and consummacioun of this document / For trewly God is yn this place.1 This statement appears midway through the Middle English transla- tion of the twelfth-centuryL atin foundation legend known as The Book of the Foundation of St Bartholomew’s Church. As a foundation legend the text’s primary aim is to narrate the construction of the church of St Bartholomew the Great in London, and to consecrate it as a sacred space by promoting its claims to sanctity. The textual and physical space of the church are conflated in the quotation above because the referent of ‘trewly God is yn this place’ is at once the church itself, the immediate subject of the foundation legend, and the translated document, in need of particular authorisation because of its status as a vernacular text. The Middle English translation was commissioned during the ‘Great Restoration’ of St Bartholomew’s at the turn of the fifteenth-century and its promotion of the sanctity of the church played a major role in the church’s strategy to re-establish itself as the dominant church in medieval London. The Middle English translation of The Book of the Foundation fol- lows a transcription of the original Latin foundation legend in British Library MS Cotton Vespasian B IX, dated c.1400.2 St Bartholomew the Great was founded in Smithfield, just outside the walls of the city of London, in 1123 by Rahere and the Latin foundation legend 1 The Book of the Foundation of St Bartholomew’s Church, ed. -

The Architecture of the Mendicant Orders in the Middle Ages: an Overview of Recent Literature

The Architecture of the Mendicant Orders in the Middle Ages: An Overview of Recent Literature Caroline Bruzelius European cities of any size had one or more mendicant convents. These institutions re- shaped the topographical, social, and economic realities of urban life in the late Middle Ages; they also often de-stabilized traditional parochial organization and created new poles of influence and activity within cities. Mendicants expanded and “anchored” new suburbs, but they sometimes also settled in the heart of a city, destroying neighborhoods in the process. As the thirteenth century progressed, friars increasingly inserted large conventual complexes within densely inhabited urban space. In Italy in particular they also carved out open areas (piazzas) for preaching. Yet, although it is hard to imagine any medieval city without its mendicant convents, the reconstruction of their presence as a physical, spiritual, economic, and social phenomenon after the systematic and thorough destruction that began as early as the sixteenth-century Reformation remains a challenging task. This essay is an overview of the main themes in recent literature on mendicant build- ings in the Middle Ages 1. A number of books on the architecture of the friars have appeared in the past twenty years. These are dominated by three broad types of analysis. The first focuses on an individual site, either a church alone or a convent as a whole (a few examples are GAI, 1994; BARCLAY LLOYD, 2004; CERVINI, DE MARCHI, 2010; DE MARCHI, PIRAZ, 2011). The second category consists of the survey that covers a region and/or an extended chrono- logical period (DELLWING, 1970, 1990; SCHENKLUHN, 2000, 2003; COOMANS, 2001; VOLTI, 2003; TODENHÖFER, 2010). -

Christmas 2018 Newsletter

The Brothers wish you God’s blessings at this Holy Cross holy festival o� the Priory Nativity of our Lord. An Anglican Benedictine Community In Canada 7:00am Matins 8:00am Eucharist (TuEsday-saTurday aT 8:00aM) 11:30am diurnum (Midday Prayer) 5:00pm Vespers 7:30pm Compline * monday is the broThErs’ “grace day” (day of ResT) 204 High Park Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, M6P 2S6 416-767-9081 | [email protected] | www.ohcpriory.com Holy Cross Priory is a monastery of the Order of the Holy Cross, a community founded in 1884 by The Reverend James Otis Sargent Huntington to provide a specifically North American expression of monasticism for Anglicans. The Order has had a ministry in Canada since the 1890s. The Priory was founded in 1973. HOLY CROSS PRIORY IS A REGIstERED CHARITY #119248946RR0001 donatiONs mAy be mAde ThrOugh cANAdAhelps.Org to “hOly crOss priOry, CanadA” ChrisTMas 2018 As we reflect on these journeys we might well take a look at our own journeying Dear Friends, through life. We are all traveling, journeying to God’s Kingdom. On this pilgrimage we are challenged, in seasons like Advent, to take note where As I walk through our neighbourhood and travel we are presently, to take our bearings and check that we are headed in the throughout the city of Toronto, where our Canadian correct direction. Joseph and Mary had no choice but to travel to Bethlehem. The priory is located, my delight in this holy season is shepherds followed the voices of angels; the magi followed the star. What is it that rekindled. -

Benedictionary.Pdf

INTRODUCTION The inspiration for this little booklet comes from two sources. The first source is a booklet developed in 1997 by Father GeorgeW. Traub, S.j., titled "Do You Speak Ignatian? A Glossary ofTerms Used in Ignatian and]esuit Circles." The booklet is published by the Ignatian Programs/Spiritual Development offICe of Xavier University, Cincinnati, Ohio. The second source, Beoneodicotionoal)', a pamphlet published by the Admissions Office of Benedictine University, was designed to be "a useful reference guide to help parents and students master the language of the college experience at Benedictine University." This booklet is not an alphabetical glossary but a directory to various offices and services. Beoneodicotio7loal)' II provides members of the campus community, and other interested individuals, with an opportunity to understand some of the specific terms used by Benedictine men and women. \\''hile Benedictine University makes a serious attempt to have all members of the campus community understand the "Benedictine Values" that underlie the educational work of the University, we hope this booklet will take the mystery out of some of the language used commonly among Benedictine monastics. This booklet was developed by Fr. David Turner, a,S.B., as part of the work of the Center for Mission and Identity at Benedictine University. I ABBESS The superior of a monastery of women, established as an abbey, is referred to as an abbess.. The professed members of the abbey are usually referred to as nuns. The abbess is elected to office following the norms contained in the proper law of the Congregation ohvhich the abbey is a member. -

Oblates of Weston Priory from the Very Beginning

Oblates of Weston Priory from the very beginning… — brother John EAR THE CLOSE OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, POPE LEO XIII N is said to have remarked, “The Benedictine Order is the only Order in the Church without any order.” The assembly of Benedictine Abbots respectfully responded in their unique way. They created the “Benedictine Confederation”. The ‘Con- federation’ unites all independent Benedictine monasteries coordinated by the ‘Abbot Primate’—the ‘first among equals’. This is in polite con- trast to Religious Orders which consist of juridically centralized reli- gious congregations. From this beginning it may be obvious that monks have their own lan- guage, or at least their own vocabulary. The word ‘oblate’ is a good exam- ple. Webster’s Dictionary says that the word is related to offering or dedi- cation. It then passes the buck by saying it is commonly used by religious. "Listen with the ear of your heart" Resorting to the religious category on the internet, the expression ‘Benedic- tine Oblates’ will produce a plethora of information—and a variety of meanings. Benedictine monasteries are deeply united in their spirituality based on the Rule of Benedict. At the same time they foster a rich variety of monastic communities with a variety of traditions and customs. Benedictine monastic communities usually welcome the Oblation of secular oblates. By adopting the spirituality and Rule of Benedict and offering to be of service to the community, oblates become a part and extension of the Benedictine family. Oblations are usually professed by individual persons who fulfill the requirements of a particular monastic community. -

The Da Vinci Code, Jesus, and History: Imagining Christianity Past and Present1

The Da Vinci Code, Jesus, and History: Imagining Christianity Past and Present1 Jeffery Tyler Did Jesus of Nazareth have a wife? Did he father a child and a lineage of kings? Do his blood descendants even now walk among us? Is the Christian messiah the victim of a tragic conspiracy, a vicious and masculine plot to conceal the true gospel and hijack the church? These are the claims of Dan Brown’s unlikely and wildly popular novel, The Da Vinci Code.2 This cliff-hanger and page-turner weaves together alleged fact and frenetic fiction in a succession of 105 rapid-fire chapters; it is a magnetic mystery and a narrative confession of faith. Should this novel and its stunning claims be taken seriously? Will the hype surrounding it soon blow over, only to be replaced by the next outlandish “big thing”? Every cultural, media, and economic indicator suggests that The Da Vinci Code is here to stay for the foreseeable future. In fact, the novel has garnered a significant global following, generating a fervent subculture and early signs of an embryonic religion. Indeed, The Da Vinci Code has significant implications not only for theologians and historians, but even more so for pastors and lay people, for discipleship and evangelism. It is vital to understand the international media event spawned by The Da Vinci Code, the book’s profound reimagining of Jesus of Nazareth and his message, and the cultural and religious currents in which church, believer, and seeker now swim. The Da Vinci Code Event This surprising bestseller opens in a dimly lit hall with a grisly murder. -

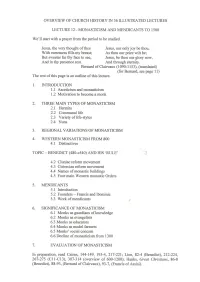

Monasticism to 1500, Mendicant Orders

OVERVIEW OF CHURCH HISTORY IN 36 ILLUSTRATED LECTURES LECTURE 12 - MONASTICISM AND MENDICANTS TO 1500 We'll start with a prayer from the period to be studied. Jesus, the very thought of thee Jesus , our only joy be thou, With sweetness fills my breast; As thou our prize wilt be; But sweeter far thy face to see, Jesus, be thou our glory now, And in thy presence rest. And through eternity. Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) , (translated) (for Bernard, see page 11) The rest of this page is an outline of this lecture . 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Asceticism and monasticism 1.2 Motivation to become a monk 2. THREE MAIN TYPES OF MONASTICISM 2.1 Hermits 2.2 Communal life 2.3 Variety of life-styles 2.4 Nuns 3. REGIONAL VARIATIONS OF MONASTICISM 4. WESTERN MONASTICISM FROM 800 4.1 Distinctives TOPIC - BENEDICT (480-c540) AND HIS 'RULE ' 4.2 Cluniac reform movement 4.3 Cistercian reform movement 4.4 Names of monastic buildings 4.5 Four main Western monastic Orders 5. MENDICANTS 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Founders -Francis and Dominic 5.3 Work of mendicants 6. SIGNIFICANCE OF MONASTICISM 6.1 Monks as guardians of knowledge 6.2 Monks as evangelists 6.3 Monks as educators 6.4 Monks as model farmers 6.5 Monks' social concern 6.6 Decline of monasticism from 1300 7. EVALUATION OF MONASTICISM In preparation , read Cairns, 144-149, 193-4, 217-221 ; Lion, 82-4 (Benedict) , 212-224 , 267-275 (Cll-C13) , 307-314 (overview of 600-1200) ; Hanks , Great Christians, 86-8 (Benedict) , 88-93, (Bernard of Clairvaux) , 93-7, (Francis of Assisi). -

Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms from Abbey to Xanten a Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms

From Abbey to Xanten A Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms From Abbey to Xanten A Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms As part of our mission at St. Norbert College, we value the importance of communio, a centuries-old charism of the Order of Premonstratensians (more commonly known as the Norbertines). Communio is characterized by mutual esteem, trust, sincerity, faith and responsibility, and is lived through open dialogue, communication, consultation and collaboration. In order for everyone to effectively engage in this ongoing dialogue, it is important that we share some of the same vocabulary and understand the concepts that shape our values as an institution. Because the college community is composed of people from diverse faith traditions and spiritual perspectives, this glossary explains a number of terms and concepts from the Catholic and Norbertine traditions with which some may not be familiar. We offer it as a guide to help people avoid those awkward moments one can experience when entering a new community – a place where people can sometimes appear to be speaking in code. While the terms in this modest pamphlet are important, the definitions are limited and are best considered general indications of the meaning of the terms rather than a complete scholarly treatment. We hope you find this useful. If there are other terms or concepts you would like to learn more about that are not covered in this guide, please feel free to contact the associate vice president for mission & student affairs at 920-403-3014 or [email protected]. In the spirit of communio, The Staff of Mission & Student Affairs When a word in a definition appears in bold type, it indicates that the word is defined elsewhere in the glossary.