1 Sleep Reduces the Semantic Coherence of Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semantic Memory - Psychology - Oxford Bibliographies

1/16/2019 Semantic Memory - Psychology - Oxford Bibliographies Semantic Memory Michael N. Jones, Johnathan Avery LAST MODIFIED: 15 JANUARY 2019 DOI: 10.1093/OBO/97801998283400231 Introduction Semantic memory refers to our general world knowledge that encompasses memory for concepts, facts, and the meanings of words and other symbolic units that constitute formal communication systems such as language or math. In the classic hierarchical view of memory, declarative memory was subdivided into two independent modules: episodic memory, which is our autobiographical store of individual events, and semantic memory, which is our general store of abstracted knowledge. However, more recent theoretical accounts have greatly reduced the independence of these two memory systems, and episodic memory is typically viewed as a gateway to semantic memory accessed through the process of abstraction. Modern accounts view semantic memory as deeply rooted in sensorimotor experience, abstracted across many episodic memories to highlight the stable characteristics and mute the idiosyncratic ones. A great deal of research in neuroscience has focused on both how the brain creates semantic memories and what brain regions share the responsibility for storage and retrieval of semantic knowledge. These include many classic experiments that studied the behavior of individuals with brain damage and various types of semantic disorders but also more modern studies that employ neuroimaging techniques to study how the brain creates and stores semantic memories. Classically, semantic memory had been treated as a miscellaneous area of study for anything in declarative memory that was not clearly within the realm of episodic memory, and formal models of meaning in memory did not advance at the pace of models of episodic memory. -

Effect of Emotional Arousal 1 Running Head

Effect of Emotional Arousal 1 Running Head: THE EFFECT OF EMOTIONAL AROUSAL ON RECALL The Effect of Emotional Arousal and Valence on Memory Recall 500181765 Bangor University Group 14, Thursday Afternoon Effect of Emotional Arousal 2 Abstract This study examined the effect of emotion on memory when recalling positive, negative and neutral events. Four hundred and fourteen participants aged over 18 years were asked to read stories that differed in emotional arousal and valence, and then performed a spatial distraction task before they were asked to recall the details of the stories. Afterwards, participants rated the stories on how emotional they found them, from ‘Very Negative’ to ‘Very Positive’. It was found that the emotional stories were remembered significantly better than the neutral story; however there was no significant difference in recall when a negative mood was induced versus a positive mood. Therefore this research suggests that emotional valence does not affect recall but emotional arousal affects recall to a large extent. Effect of Emotional Arousal 3 Emotional arousal has often been found to influence an individual’s recall of past events. It has been documented that highly emotional autobiographical memories tend to be remembered in better detail than neutral events in a person’s life. Structures involved in memory and emotions, the hippocampus and amygdala respectively, are joined in the limbic system within the brain. Therefore, it would seem true that emotions and memory are linked. Many studies have investigated this topic, finding that emotional arousal increases recall. For instance, Kensinger and Corkin (2003) found that individuals remember emotionally arousing words (such as swear words) more than they remember neutral words. -

Working Memory and Cued Recall Max V

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern University Honors Program Theses 2016 Working memory and cued recall Max V. Fey 8602950 Karen Naufel Georgia Southern University Lawrence Locker Georgia Southern University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Fey, Max V. 8602950; Naufel, Karen; and Locker, Lawrence, "Working memory and cued recall" (2016). University Honors Program Theses. 220. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/honors-theses/220 This thesis (open access) is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Program Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Working Memory and Cued Recall Working Memory and Cued Recall An Honors Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Psychology. By Maximilian Fey Under the mentorship of Dr. Karen Naufel ABSTRACT Previous research has found that individuals with high working memory have greater recall capabilities than those with low working memory (Unsworth, Spiller, & Brewers, 2012). Research did not test the extent to which cues affect one’s recall ability in relation to working memory. The present study will examine this issue. Participants completed a working memory measure. Then, they were provided with cued recall tasks whereby they recalled Facebook friends. The cues varied to be no cues, ambiguous cues high in imageability, and cues directly related to Facebook. The results showed that there was no difference between individual’s ability to recall their Facebook friends and their working memory scores. -

Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: the Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity

brain sciences Article Post-Encoding Stress Does Not Enhance Memory Consolidation: The Role of Cortisol and Testosterone Reactivity Vanesa Hidalgo 1,* , Carolina Villada 2 and Alicia Salvador 3 1 Department of Psychology and Sociology, Area of Psychobiology, University of Zaragoza, 44003 Teruel, Spain 2 Department of Psychology, Division of Health Sciences, University of Guanajuato, Leon 37670, Mexico; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychobiology and IDOCAL, University of Valencia, 46010 Valencia, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-978-645-346 Received: 11 October 2020; Accepted: 15 December 2020; Published: 16 December 2020 Abstract: In contrast to the large body of research on the effects of stress-induced cortisol on memory consolidation in young people, far less attention has been devoted to understanding the effects of stress-induced testosterone on this memory phase. This study examined the psychobiological (i.e., anxiety, cortisol, and testosterone) response to the Maastricht Acute Stress Test and its impact on free recall and recognition for emotional and neutral material. Thirty-seven healthy young men and women were exposed to a stress (MAST) or control task post-encoding, and 24 h later, they had to recall the material previously learned. Results indicated that the MAST increased anxiety and cortisol levels, but it did not significantly change the testosterone levels. Post-encoding MAST did not affect memory consolidation for emotional and neutral pictures. Interestingly, however, cortisol reactivity was negatively related to free recall for negative low-arousal pictures, whereas testosterone reactivity was positively related to free recall for negative-high arousal and total pictures. -

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory

The Effects of Happy and Sad Emotional States on Episodic Memory Richard Topolski ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Sarah R. Daniel ([email protected]) Department of Psychology, Augusta State University 2500 Walton Way, Augusta GA 30904 USA Introduction methodology for measuring EM largely independent of semantic memory. Episodic memory (EM) is composed of personally experienced events in which ‘the what, where, and when’ Method are essential components while semantic memory is simply composed of accumulated facts about the world (Tulving, Happy, neutral, or sad mood states were induced in 88 2002). A wide variety of tasks have been used to tap students via a 20 minute long viewing of either a stand-up episodic memory including: recalling words from an early comedy routine, a documentary, or holocaust footage. learned list; yes-no recognition of previously presented Immediately following the mood induction, participants common objects or pictures; and free recall of past personal engaged in eight interactive tasks which involved both experiences. These tasks are used to evaluate episodic familiar objects (pennies and paperclips) and novel memory because in order to know which words, pictures, or geometric forms created by bending paper clips with blue experiences to retrieve, some contextual (episodic) beads into unique shapes, (Rock, Schreilber, and Ro, 1994). information must first be accessed (Mayes & Roberts, A four-item force-choice recognition test for the novel 2001). While all of these measures seem to share this geometric forms was employed, with the task name serving contextual component, none adequately examines the as the retrieval cue. -

Examining the Effect of Interference on Short-Term Memory Recall of Arabic Abstract and Concrete Words Using Free, Cued, and Serial Recall Paradigms

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 6; December 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Examining the Effect of Interference on Short-term Memory Recall of Arabic Abstract and Concrete Words Using Free, Cued, and Serial Recall Paradigms Ahmed Mohammed Saleh Alduais (Corresponding author) Department of Linguistics, Social Sciences Institute Ankara University, 06100 Sıhhiye, Ankara, Turkey E-mail: [email protected] Yasir Saad Almukhaizeem Department of Linguistics and Translation, College of Languages and Translation King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.7 Received: 29/05/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.7 Accepted: 18/08/2015 The research is financed by Research Centre in the College of Languages and Translation Studies and the Deanship of Scientific Research, King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Abstract Purpose: To see if there is a correlation between interference and short-term memory recall and to examine interference as a factor affecting memory recalling of Arabic and abstract words through free, cued, and serial recall tasks. Method: Four groups of undergraduates in King Saud University, Saudi Arabia participated in this study. The first group consisted of 9 undergraduates who were trained to perform three types of recall for 20 Arabic abstract and concrete words. The second, third and fourth groups consisted of 27 undergraduates where each group was trained only to perform one recall type: free recall, cued recall and serial recall respectively. -

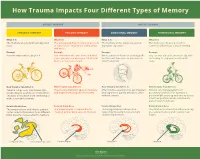

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory

How Trauma Impacts Four Different Types of Memory EXPLICIT MEMORY IMPLICIT MEMORY SEMANTIC MEMORY EPISODIC MEMORY EMOTIONAL MEMORY PROCEDURAL MEMORY What It Is What It Is What It Is What It Is The memory of general knowledge and The autobiographical memory of an event The memory of the emotions you felt The memory of how to perform a facts. or experience – including the who, what, during an experience. common task without actively thinking and where. Example Example Example Example You remember what a bicycle is. You remember who was there and what When a wave of shame or anxiety grabs You can ride a bicycle automatically, with- street you were on when you fell off your you the next time you see your bicycle out having to stop and recall how it’s bicycle in front of a crowd. after the big fall. done. How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It How Trauma Can Affect It Trauma can prevent information (like Trauma can shutdown episodic memory After trauma, a person may get triggered Trauma can change patterns of words, images, sounds, etc.) from differ- and fragment the sequence of events. and experience painful emotions, often procedural memory. For example, a ent parts of the brain from combining to without context. person might tense up and unconsciously make a semantic memory. alter their posture, which could lead to pain or even numbness. Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area Related Brain Area The temporal lobe and inferior parietal The hippocampus is responsible for The amygdala plays a key role in The striatum is associated with producing cortex collect information from different creating and recalling episodic memory. -

Episodic Memory-From Brain to Mind

HIPPOCAMPUS 16:691–703 (2006) Episodic Memory—From Brain to Mind Janina Ferbinteanu,* Pamela J. Kennedy, and Matthew L. Shapiro ABSTRACT: Neuronal mechanisms of episodic memory, the conscious by the rapid formation of relational representations of recollection of autobiographical events, are largely unknown because highly processed sensory information that are used electrophysiological studies in humans are conducted only in excep- tional circumstances. Unit recording studies in animals are thus crucial flexibly and are not necessarily expressed through overt for understanding the neurophysiological substrate that enables people motor behavior. Episodic memory is also sensitive to to remember their individual past. Two features of episodic memory— lesions of the prefrontal cortex (Wheeler et al., 1995; autonoetic consciousness, the self-aware ability to \travel through Nyberg et al., 2000; Burgess et al., 2002; Wheeler time", and one-trial learning, the acquisition of information in one and Stuss, 2003), develops later in an individual’s life, occurrence of the event—raise important questions about the validity of animal models and the ability of unit recording studies to capture essen- encodes events within a personal framework, and pos- tial aspects of memory for episodes. We argue that autonoetic experi- sesses a temporal dimension because it is oriented ence is a feature of human consciousness rather than an obligatory as- towards the past and the future (Tulving, 1972, 2001, pect of memory for episodes, and that episodic memory is reconstruc- 2002; Tulving and Markowitsch, 1998). Autobio- tive and thus its key features can be modeled in animal behavioral tasks graphic information contains memories about what that do not involve either autonoetic consciousness or one-trial learning. -

PSYC20006 Notes

PSYC20006 BIOLOGICAL PSYCHOLOGY PSYC20006 1 COGNITIVE THEORIES OF MEMORY Procedural Memory: The storage of skills & procedures, key in motor performance. It involves memory systems that are independent of the hippocampal formation, in particular, the cerebellum, basal ganglia, cortical motor sites. Doesn't involve mesial-temporal function, basal forebrain or diencephalon. Declarative memory: Accumulation of facts/data from learning experiences. • Associated with encoding & maintaining information, which comes from higher systems in the brain that have processed the information • Information is then passed to hippocampal formation, which does the encoding for elaboration & retention. Hippocampus is in charge of structuring our memories in a relational way so everything relating to the same topic is organized within the same network. This is also how memories are retrieved. Activation of 1 piece of information will link up the whole network of related pieces of information. Memories are placed into an already exiting framework, and so memory activation can be independent of the environment. MODELS OF MEMORY Serial models of Memory include the Atkinson-Shiffrin Model, Levels of Processing Model & Tulving’s Model — all suggest that memory is processed in a sequential way. A parallel model of memory, the Parallel Distributed Processing Model, is one which suggests types of memories are processed independently. Atkinson-Shiffrin Model First starts as Sensory Memory (visual / auditory). If nothing is done with it, fades very quickly but if you pay attention to it, it will move into working memory. Working Memory contains both new information & from long-term memory. If it goes through an encoding process, it will be in long-term memory. -

Research Article Arthur P. Shimamura

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Article MEMORY AND COGNITIVE ABILITIES IN UNIVERSITY PROFESSORS: Evidence for Successful Aging Arthur P. Shimamura,' Jane M. Berry,^ Jennifer A. Mangels,' Cheryl L. Rusting,^ and Paul J. Jurica* 'University of California, Berkeley, 'University of Richmond, and ^University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Abstract—Professors from the University of California at Schaie, 1990, 1994) That is, professors may develop efficient Berkeley were administered a 90-min test battery of cognitive use of cognitive abiliues or strategies that may prevent or mit- performance that included measures of reaction time, paired- igate aging effects associate learning, working memory, and prose recall Age ef- University professors between the ages of 30 and 71 years fects among the professors were observed on tests of reaction were administered a battery of memory and cognitive tests The time, paired-associate memory, and some aspects of working particular tests were chosen because they were known to be memory Age effects were not observed on measures of proac- sensitive markers of age-related changes (e g , choice reaction tive interference and prose recall, though age-related declines time, free recall) or known to be associated with circumscnbed are generally observed m standard groups of elderly individu- neurological dysfunction (e g , medial temporal or frontal lobe als The findings suggest that age-related decrements in certain impairment) Several hypotheses were entertained with regard cognitive functions may be mitigated in intelligent, -

High 1 Effectiveness of Echoic and Iconic Memory in Short-Term and Long-Term Recall Courtney N. High 01/14/13 Mr. Mengel Psychol

High 1 Effectiveness of Echoic and Iconic Memory in Short-term and Long-term Recall Courtney N. High 01/14/13 Mr. Mengel Psychology 1 High 2 Abstract Objective: To see whether iconic memory or echoic memory is more effective at being stored and recalled as short-term and long-term memory in healthy adults. Method: Eight healthy adults between the ages of 18 and 45 were tested in the study. Participants were shown a video containing ten pictures and ten sounds of easily recognizable objects. Participants were asked to recall as many items as they could immediately after the video and were then asked again after a series of questions. Results: In younger adults more visual objects are able to be recalled both short and long term, but with older adults, in short term recall, the same number of sound and visual items where remembered, and with long term recall, sound items were remembered slightly better. Results also showed that iconic memory fades faster than echoic memory. Conclusion: The ability to store and recall iconic and echoic information both short and long term varies with age. The study has several faults including relying on self-reporting on health for participants, and testing environments not being quiet in all tests. Introduction There are three main different types of memory: Sensory memory, short-term memory, and long-term memory. Sensory memory deals with the brief storage of information immediately after stimulation. Sensory memory is then converted to short-term memory if deemed necessary by the brain where it is held. After that, some information will then be stored as long-term memory for later recall. -

Examining the Relationship Between Free Recall and Immediate Serial Recall: the Serial Nature of Recall and the Effect of Test Expectancy

Memory & Cognition 2008, 36 (1), 20-34 doi: 10.3758/MC.36.1.20 Examining the relationship between free recall and immediate serial recall: The serial nature of recall and the effect of test expectancy PARVEEN BHATARAH London Metropolitan University, London, England GEOFF WARD University of Essex, Colchester, England AND LYDIA TAN City University London, London, England In two experiments, we examined the relationship between free recall and immediate serial recall (ISR), using a within-subjects (Experiment 1) and a between-subjects (Experiment 2) design. In both experiments, partici- pants read aloud lists of eight words and were precued or postcued to respond using free recall or ISR. The serial position curves were U-shaped for free recall and showed extended primacy effects with little or no recency for ISR, and there was little or no difference between recall for the precued and the postcued conditions. Critically, analyses of the output order showed that although the participants started their recall from different list positions in the two tasks, the degree to which subsequent recall was serial in a forward order was strikingly similar. We argue that recalling in a serial forward order is a general characteristic of memory and that performance on ISR and free recall is underpinned by common memory mechanisms. Free recall and immediate serial recall (ISR) are two correct order on 50% of the trials. The classic explanation immediate memory tasks in which participants are pre- for the memory span is that it reflects the capacity limita- sented with lists of words to study, one word at a time, tions of the STS, in terms of either the number of chunks and then, after the presentation of the last word in a list, of items that can be recalled (e.g., Miller, 1956) or the they must try to recall as many of the items as they can.