Ray Flaherty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 4 Article 1 2006 It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes Michael A. McCann Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Michael A. McCann, It's Not About the Money: The Role of Preferences, Cognitive Biases, and Heuristics Among Professional Athletes, 71 Brook. L. Rev. (2006). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol71/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. ARTICLES It’s Not About the Money: THE ROLE OF PREFERENCES, COGNITIVE BIASES, AND HEURISTICS AMONG PROFESSIONAL ATHLETES Michael A. McCann† I. INTRODUCTION Professional athletes are often regarded as selfish, greedy, and out-of-touch with regular people. They hire agents who are vilified for negotiating employment contracts that occasionally yield compensation in excess of national gross domestic products.1 Professional athletes are thus commonly assumed to most value economic remuneration, rather than the “love of the game” or some other intangible, romanticized inclination. Lending credibility to this intuition is the rational actor model; a law and economic precept which presupposes that when individuals are presented with a set of choices, they rationally weigh costs and benefits, and select the course of † Assistant Professor of Law, Mississippi College School of Law; LL.M., Harvard Law School; J.D., University of Virginia School of Law; B.A., Georgetown University. Prior to becoming a law professor, the author was a Visiting Scholar/Researcher at Harvard Law School and a member of the legal team for former Ohio State football player Maurice Clarett in his lawsuit against the National Football League and its age limit (Clarett v. -

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 7, No. 5 (1985) THE 1920s ALL-PROS IN RETROSPECT By Bob Carroll Arguments over who was the best tackle – quarterback – placekicker – water boy – will never cease. Nor should they. They're half the fun. But those that try to rank a player in the 1980s against one from the 1940s border on the absurd. Different conditions produce different results. The game is different in 1985 from that played even in 1970. Nevertheless, you'd think we could reach some kind of agreement as to the best players of a given decade. Well, you'd also think we could conquer the common cold. Conditions change quite a bit even in a ten-year span. Pro football grew up a lot in the 1920s. All things considered, it's probably safe to say the quality of play was better in 1929 than in 1920, but don't bet the mortgage. The most-widely published attempt to identify the best players of the 1920s was that chosen by the Pro Football Hall of Fame Selection Committee in celebration of the NFL's first 50 years. They selected the following 18-man roster: E: Guy Chamberlin C: George Trafton Lavie Dilweg B: Jim Conzelman George Halas Paddy Driscoll T: Ed Healey Red Grange Wilbur Henry Joe Guyon Cal Hubbard Curly Lambeau Steve Owen Ernie Nevers G: Hunk Anderson Jim Thorpe Walt Kiesling Mike Michalske Three things about this roster are striking. First, the selectors leaned heavily on men already enshrined in the Hall of Fame. There's logic to that, of course, but the scary part is that it looks like they didn't do much original research. -

Bobby Mitchell

PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME TEACHER ACTIVITY GUIDE 2019-2020 EDITIOn WASHInGTOn REDSKInS Team History With three Super Bowl championships, the Washington Redskins are one of the NFL’s most dominant teams of the past quarter century. But the organization’s glorious past dates back almost 60 years and includes five world championships overall and some of the most innovative people and ideas the game has ever known. From George Preston Marshall to Jack Kent Cooke, from Vince Lombardi to Joe Gibbs, from Sammy Baugh to John Riggins, plus the NFL’s first fight song, marching band and radio network, the Redskins can be proud of an impressive professional football legacy. George Preston Marshall was awarded the inactive Boston franchise in July 1932. He originally named the team “Braves” because it used Braves Field, home of the National League baseball team. When the team moved to Fenway Park in July 1933, the name was changed to Redskins. A bizarre situation occurred in 1936, when the Redskins won the NFL Eastern division championship but Marshall, unhappy with the fan support in Boston,moved the championship game against Green Bay to the Polo Grounds in New York. Their home field advantage taken away by their owner, the Redskins lost. Not surprisingly, the Redskins moved to Washington, D.C., for the 1937 season. Games were played in Griffith Stadium with the opener on September 16, 1937, being played under flood lights. That year,Marshall created an official marching band and fight song, both firsts in the National Football League. That season also saw the debut of “Slinging Sammy” Baugh, a quarterback from Texas Christian who literally changed the offensive posture of pro football with his forward passing in his 16-season career. -

17 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 10, 2007 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 17 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Paul Tagliabue, Thurman Thomas, Michael Irvin, and Bruce Matthews are among the 17 finalists that will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Miami, Florida on Saturday, February 3, 2007. Joining these four finalists, are 11 other modern-era players and two players nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee. The Senior Committee nominees, announced in August 2006, are former Cleveland Browns guard Gene Hickerson and Detroit Lions tight end Charlie Sanders. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends Fred Dean and Richard Dent; guards Russ Grimm and Bob Kuechenberg; punter Ray Guy; wide receivers Art Monk and Andre Reed; linebackers Derrick Thomas and Andre Tippett; cornerback Roger Wehrli; and tackle Gary Zimmerman. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 17 finalists with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Fred Dean – Defensive End – 1975-1981 San Diego Chargers, 1981- 1985 San Francisco 49ers Richard Dent – Defensive End – 1983-1993, 1995 Chicago Bears, 1994 San Francisco 49ers, 1996 Indianapolis Colts, 1997 Philadelphia Eagles Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Ray Guy – Punter – 1973-1986 Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders Gene Hickerson – Guard – 1958-1973 Cleveland Browns Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Great Forgotten Ends of the 1930'S

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 15, No. 1 (1993) Great Forgotten Ends of the 1930's by Stan Grosshandler There was once a position called END! The end played on both sides of the line of scrimmage; therefore, there was a left end and a right end. There were no split ends, tight ends, wide receivers, flankers, wide outs, or anything else. There were just plain ENDS! Now end was a very difficult position to play. You had to catch passes all over the field, block a tackle who vastly outweighed you, and stop end sweeps by throwing yourself into an interference that consisted of two running guards built like tanks and a pretty hefty blocking back built like a bull. You were expected to play sixty minutes, which often meant you had to chase a pass the length of the field, then block that monster in front of you, and next go on defense and break up the interference. Some days it was just plain hell! Four ends from the 1930's, Don Hutson, Red Badgro, Bill Hewitt, and Wayne Millner are honored in the Hall of Fame. A fifth, Ray Flaherty, is in the Hall for his coaching success, but was a very good end as a player. During the early years of the NFL, George Halas, an old right end himself, did a pretty good job of collecting most of the talent. Besides Hewitt he had Luke Johnsos, Bill Karr, Eggs Manske, Dick Plasman, and George Wilson. Johnsos and Karr played the right side opposite Hewitt. With the Bears from 1929 through 1936 Luke had a career total of 87 receptions and 19 TD's. -

How to Get from Dayton to Indianapolis by Way of Brooklyn, Boston, New York, Dallas, Hershey and Baltimore

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 17, No. 5 (1995) HOW TO GET FROM DAYTON TO INDIANAPOLIS BY WAY OF BROOKLYN, BOSTON, NEW YORK, DALLAS, HERSHEY AND BALTIMORE By Bob Carroll Originally published in Ragtyme Sports Once upon a time -- well, in March of 1995, to be exact -- Ragtyme Sports published Rick Hines' story on Y.A. Tittle, one of my all-time favorite bald quarterbacks. Maybe I enjoyed reminiscing about Y.A. too much because I read right past an error in the article without noticing it, an error that has since given rise to a series of letter-to-the-editor corrections that may have simply confused the issue further. To remind everybody, what Rick wrote was "... the [Baltimore] Colts were one of four AAFC teams taken in by the NFL. The other teams from the defunct AAFC to merge with the NFL were the [Cleveland] Browns, New York Yankees and San Francisco 49ers." The question seems simple enough: which teams and how many of them from the old All-America Football Conference (1946-1949) were taken into the the National Football League in 1950? What Rick wrote was wrong. But also it was sort of right, as I will explain later. Eric Minde, a reader who knows his AAFC potatoes (as my sainted grandpa used to say}, jumped all over Rick. In Issue 4, Eric said: "... the article about Y.A. Tittle identifies the New York Yankees as an AAFC team that transferred to the NFL -- this is also wrong! The New York Yankees folded with the AAFC -- it was the Boston Yanks already in the NFL before the AAFC came into existence that became the New York Bulldogs, then later renamed the New York Yanks." This is right as far as it goes. -

All-Pros of 1931

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 5, No. 3 (1983) ALL-PROS OF 1931 By John Hogrogian As one would expect of three time champions, the Green Bay Packers flooded the 1931 honor rolls. Eleven Packers were mentioned on at least one published All-Pro team. The habitual Green Bay championship was not without challenge, as the Portsmouth Spartans rocketed out of obscurity to finish only one game off the pace. In their NFL debut in 1930, the Spartans lost more often than they won. With no nonsense coach Potsy Clark recruited from the college ranks, the Spartans assembled a fine collection of new players, some of them rookies and some of them from other pro teams. Seven Portsmouth players won berths on someone's All-Pro team, a fitting compliment to the club's fine finish in the standings. The annual poll of writers, team managers, and game officials placed four Packers and two Spartans on the first team. First Team E- Lavern Dilweg, GB E- Red Badgro, NY T- Cal Hubbard, GB T- George Christensen, Port G- Mike Michalske, GB G- Butch Gibson, NY C- Frank McNally, ChiC Q- Dutch Clark, Port H- Red Grange, ChiB H- Johnny Blood, GB F- Ernie Nevers, ChiC Second Team Third Team E- Luke Johnsos, ChiB E- Ray Flaherty, NY E- Bill McKalip, Port E- Al Rose, Prov T- Jap Douds, Port T- Bill Owen, NY T- Dick Stahlman, GB T- Lou Gordon, Bkn G- Walt Kiesling, ChiC G- Zuck Carlson, ChiB G- Al Graham, Prov G- Maury Bodenger, Port C- Mel Hein, NY C- Nate Barrager,Fra-GB Q- Red Dunn, GB Q- Benny Friedman, NY H- Ken Strong, SI H- Roy Lumpkin, Port H- Glenn Presnell, Port H- Dick Nesbitt, ChiB F- Bo Molenda, GB F- Herb Joesting,Fra-ChiB Sources: Green Bay Press-Gazette, Dec. -

15 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact January 11, 2006 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 15 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Troy Aikman, Warren Moon, Thurman Thomas, and Reggie White, four first-year eligible candidates, are among the 15 finalists who will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Detroit, Michigan on Saturday, February 4, 2006. Joining the first-year eligible players as finalists, are nine other modern-era players and a coach and player nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Seniors Committee. The Seniors Committee nominees, announced in August 2005, are John Madden and Rayfield Wright. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends L.C. Greenwood and Claude Humphrey; linebackers Harry Carson and Derrick Thomas; offensive linemen Russ Grimm, Bob Kuechenberg and Gary Zimmerman; and wide receivers Michael Irvin and Art Monk. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 15 finalists with their positions, teams, and years follow: Troy Aikman – Quarterback – 1989–2000 Dallas Cowboys Harry Carson – Linebacker – 1976-1988 New York Giants L.C. Greenwood – Defensive End – 1969-1981 Pittsburgh Steelers Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Claude Humphrey – Defensive End – 1968-1978 Atlanta Falcons, 1979-1981 Philadelphia Eagles (injured reserve – 1975) Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 Dallas Cowboys Bob Kuechenberg – Guard – 1970-1984 Miami Dolphins -

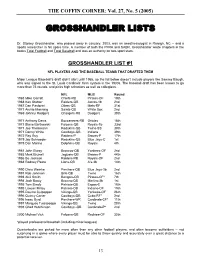

Grosshandler Lists

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 27, No. 5 (2005) GROSSHANDLER LISTS Dr. Stanley Grosshandler, who passed away in January, 2003, was an anesthesiologist in Raleigh, NC -- and a sports researcher in his spare time. A member of both the PFRA and SABR, Grosshandler wrote chapters in the books Total Football and Total Baseball and was an authority on two-sport stars. GROSSHANDLER LIST #1 NFL PLAYERS AND THE BASEBALL TEAMS THAT DRAFTED THEM Major League Baseball’s draft didn’t start until 1965, so the list below doesn’t include players like Sammy Baugh, who was signed to the St. Louis Cardinals’ farm system in the 1930s. The baseball draft has been known to go more than 75 rounds, and picks high schoolers as well as collegians. NFL MLB Round 1965 Mike Garrett Chiefs-RB Pirates-OF 19th 1968 Ken Stabler Raiders-QB Astros-1b 2nd 1967 Dan Pastorini Oilers-QB Mets-RF 31st 1971 Archie Manning Saints-QB White Sox 2nd 1969 Johnny Rodgers Chargers-RB Dodgers 38th 1971 Anthony Davis Buccaneers-RB Orioles 18th 1971 Steve Bartkowski Falcons-QB Royals-1b 33rd 1971 Joe Theismann Redskins-QB Twins-SS 39th 1971 Danny White Cowboys-QB Indians 39th 1972 Ray Guy Raiders-P Braves-P 17th 1979 Jay Schroeder Redskins-QB Blue Jays-C 1st 1979 Dan Marino Dolphins-QB Royals 4th 1981 John Elway Broncos-QB Yankees-OF 2nd 1985 Mark Brunell Jaguars-QB Braves-P 44th 1986 Bo Jackson Raiders-RB Royals-OF 2nd 1988 Rodney Peete Lions-QB A’s-3b 14th 1990 Chris Weinke Panthers-QB Blue Jays-3b 2nd 1991 Rob Johnson Bills-QB Twins 16th 1993 Akili Smith Bengals-QB Pirates-OF* 7th 1994 Josh -

Ozzie Newsome Cleveland’S Own Helped Revolutionize Tight End Position

THE COFFIN CORNER: Vol. 27, No. 4 (2005) Ozzie Newsome Cleveland’s Own Helped Revolutionize Tight End Position By Roger Gordon (Originally published in The Free Press, Canton, Ohio, Aug. 1, 1999) Ozzie Newsome has a reason, it seems, to return to Canton every nine years. In the summer of 1981, Newsome began his fourth season as the Cleveland Browns’ starting tight end as the Browns defeated the Atlanta Falcons, 24-10, in the Pro Football Hall of Fame Game. In the summer of 1990, Newsome began his final season as the Browns were blanked by the Chicago Bears, 13-0, in the HOF contest. This week, "The Wizard of Oz" will return to Canton once again. But instead of catching passes and making blocks on Pro Football Hall of Fame Field in Fawcett Stadium, the great tight end will be catching praise and making speeches right next door on the front steps of the Hall of Fame. Newsome is one of five men who will be inducted into the pro grid shrine two days before the "new" Browns tackle the Dallas Cowboys in the Hall of Fame Game, a contest that will be beamed across the country on a special edition of ABC’s Monday Night Football. Newsome was understandably excited when he first received the news of his induction. After all, he was beginning to look a lot like pro football’s version of Susan Lucci, the star of the soap opera All My Children, who went nearly two decades before finally winning a daytime Emmy Award, an honor many thought was absurdly overdue.