The James Allen Freeman House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

FHR-a-300 (11-78) United States Department off the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______________ 1. Name historic 444s4oifHir1tesotHoee^^ .(fafrtrfat* : I Bungalow Court and/or common Same 2. Location street & number An area of 2.27 sg. miles in central Pasadena._____n/a not for publication city, town Pasadena______________n/a. vicinity of____congressional district 22nd_____ state California code 06 county Los Angeles code 037 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) " private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process _JL_ yes: restricted government scientific TH EM AT I C being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation GROUP X n/a no military other- 4. Owner of Property name Multiple Ownership - see continuation sheet street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Office of the Assessor, County of Los Angeles street & number 300 East Walnut Street city, town Pasadena state California 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Pasadena Architectural and titie Historical Inventory______ has this property been determined eligible? __ yes no date 1976-1981 . federal . state __ county X local Urban Conservation Section of the Housing and Community depos.tory for survey records pfiVPlopment Department of the City of Pasadena city, town Pasadena state California 7. Description________________ Condition Check one Check one _^excellent ^| __ deteriorated X unaltered . -

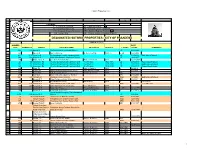

Designated Historic Properties

Historic Properties List A B C D E F G H I 1 2 LISTINGS: 3 L - Designated Landmark LD - Landmark District 4 M - Designated Monument NHL - National Historic Landmark 5 GG - Greene & Greene Structure NRD - National Register District 6 HS - Historic Sign NRI - National Register Individual Property 7 8 DESIGNATED HISTORIC PROPERTIES - CITY OF PASADENA 9 10 Updated 9/4/2018 NUMBER DATE 11 from NUMBER to STREET HISTORIC NAME ARCHITECT YR BUILT LISTING LISTED COMMENTS 12 338 348 Adena St Garfield Heights Landmark District LD 3/29/1999 13 341 Adena St Adena Mansion Getschell (attrib) 1885 ca L, LD 1/23/2006 14 941 1011 Allen Av N No Pasadena Heights Landmark Dist LD 3/13/2006 Odd side of street 15 300 522 Allen Av S Rose Villa-Oakdale Landmark District LD 10/2/2017 16 160 162 Altadena Dr N Lamanda Park Substation Robert Ainsworth 1933 L 12/17/2007 17 42 104 Annandale Rd Weston-Bungalowcraft Landmark Dist Rex Weston 1925-1935 LD 2/26/2011 Even side of street 18 112 152 Annandale Rd Weston-Bungalowcraft Landmark Dist Rex Weston 1925-1935 LD 2/26/2011 Both sides of street 19 160 174 Annandale Rd Weston-Bungalowcraft Landmark Dist Rex Weston 1925-1935 LD 2/26/2011 Even side of street 20 580 Arbor St John L. Pugsley 1961 L 2/5/2018 21 777 Arden Rd Walter and Margaret Candy House John William Chard 1926 L 6/2/2008 22 860 Arden Rd A.F. Brockway House Greene & Greene 1899 GG 23 270 Arlington Storrer-Stearns Japanese Garden NRI 2/15/2005 24 1005 1126 Armada Dr Prospect Historic District NRD 4/7/1983 Both sides of street 25 20 24 Arroyo Bl S Vista Del -

Preserving the Past and Planning the Future in Pasadena, Riverside and San Bernardino

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2010 Preserving the past and planning the future in Pasadena, Riverside and San Bernardino Charles Conway Palmer University of Nevada Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Civic and Community Engagement Commons, United States History Commons, and the Urban Studies Commons Repository Citation Palmer, Charles Conway, "Preserving the past and planning the future in Pasadena, Riverside and San Bernardino" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 194. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1439041 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESERVING THE PAST AND PLANNING THE FUTURE IN PASADENA, RIVERSIDE, AND SAN BERNARDINO by Charles Conway Palmer Bachelor of Science California State Polytechnic University, -

GC 1323 Historic Sites Surveys Repository

GC 1323 Historic Sites Surveys Repository: Seaver Center for Western History Research, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Span Dates: 1974-1996, bulk 1974-1978 Conditions Governing Use: Permission to publish, quote or reproduce must be secured from the repository and the copyright holder Conditions Governing Access: Research is by appointment only Source: Surveys were compiled by Tom Sitton, former Head of History Department, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Background: In 1973, the History Department of the Natural History Museum was selected to conduct surveys of Los Angeles County historic sites as part of a statewide project funded through the National Preservation Act of 1966. Tom Sitton was appointed project facilitator in 1974 and worked with various historical societies to complete survey forms. From 1976 to 1977, the museum project operated through a grant awarded by the state Office of Historic Preservation, which allowed the hiring of three graduate students for the completion of 500 surveys, taking site photographs, as well as to help write eighteen nominations for the National Register of Historic Places (three of which were historic districts). The project concluded in 1978. Preferred Citation: Historic Sites Surveys, Seaver Center for Western History Research, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History Special Formats: Photographs Scope and Content: The Los Angeles County historic site surveys were conducted from 1974 through 1978. Compilation of data for historic sites continued beyond 1978 until approximately 1996, by way of Sitton's efforts to add application sheets prepared for National Register of Historic Places nominations. These application forms provide a breadth of information to supplement the data found on the original survey forms. -

Bungalow Courts in Pasadena - Planning & Community Development Department ATTACHMENT E Bungalow Courts in Pasadena

7/1/2020 Bungalow Courts in Pasadena - Planning & Community Development Department ATTACHMENT E Bungalow Courts in Pasadena • Planning Division • Design and Historic Preservation • Historic Preservation • Projects and Studies • Bungalow Courts in Pasadena Pasadena is generally attributed as the birthplace of the bungalow court, a form of multi-family housing that involved groupings of small one-story individual houses or duplexes oriented around a common landscaped courtyard, usually on one property. Developed from 1909 through 1942, bungalow courts evolved from transient, seasonal use to permanent residences and appeared in many architectural styles. Having a wide variety of character and appearance, the city’s inventory of bungalow courts is signi˚cant as a regional type of low-density multi-family housing that combined the individual privacy of a single residence with shared community space. Saint Francis Courts (Courtesy of the Archives, Pasadena Museum of History) The city’s ˚rst bungalow court was St. Francis Court (photo above), designed by Sylvanus Marston and built in 1909. This court, on the north side of East Colorado Boulevard at the current intersection of North Oak Knoll Avenue, was made up of 11 bungalows, each with its own garden and with a driveway through the center. The bungalows had between one and three bedrooms, modern conveniences, and high- quality detailing common in the Arts and Crafts period. An Arroyo stone and brick gateway was at the entrance (the court was disassembled and partially relocated to make way for the extension of Oak Knoll north to Union Street). Although the original con˚guration of St. Francis Court has been lost, ˚ve of the original bungalows survive as a grouping on individual lots at the corner of South Catalina Avenue and Cornell Road.