Interviews with Jim Hunter and Others

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the HIGHLAND COUNCIL the Proposal Is to Establish a Catchment Area for Bun-Sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar, and a Gaelic Medium

THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL The proposal is to establish a catchment area for Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar, and a Gaelic Medium catchment area for Lochaber High School EDUCATIONAL BENEFITS STATEMENT THIS IS A PROPOSAL PAPER PREPARED IN TERMS OF THE EDUCATION AUTHORITY’S AGREED PROCEDURE TO MEET THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE SCHOOLS (CONSULTATION) (SCOTLAND) ACT 2010 INTRODUCTION The Highland Council is proposing, subject to the outcome of the statutory consultation process: • To establish a catchment area for Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar. The new Gàidhlig Medium (GM) catchment will overlay the current catchments of Banavie Primary School, Caol Primary School, Inverlochy Primary School, Lundavra Primary School, Roy Bridge Primary School, Spean Bridge Primary School, and St. Bride’s Primary School • To formalise the current arrangements relating to Gàidhlig Medium Education (GME) in related secondary schools, under which the catchment area for Lochaber High School will apply to both Gàidhlig Medium and English Medium education, and under which pupils from the St. Bride’s PS catchment (part of the Kinlochleven Associated School Group) have the right to attend Lochaber High School to access GME, provided they have previously attended Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar. • Existing primary school catchments for the provision of English Medium education will be unaffected. • The proposed changes, if approved, will be implemented at the conclusion of the statutory consultation process. If implemented as drafted, the proposed catchment for Bun-sgoil Ghàidhlig Loch Abar will include all of the primary school catchments within the Lochaber ASG, except for that of Invergarry Primary School. The distances and travel times to Fort William from locations within the Invergarry catchment make it unlikely that GM provision would be attractive to parents of primary school age children, and dedicated transport from the Invergarry catchment could result in excessive cost being incurred. -

FOR SALE Craignaha, Duror, Appin, PA38

FOR SALE T: 01631 569 466 [email protected] | www.west-property.co.uk Property Sales & Lettings Craignaha, Duror, Appin, PA38 4BS Detached Bungalow 3 bedrooms/3 bathrooms Stunning views 3 serviced out buildings Plentiful off road parking EPC - F Asking price of £250,000 Craignaha, Duror, Appin, PA38 4BS Asking Price of £250,000 OVERVIEW Craignaha is a well presented detached bungalow with beautiful countryside views. The property has a cosy feeling as you walk into the spacious and light hallway. Directly to the left of the hallway is a double bedroom with room for extra storage and a small chest of draws. Next door is the cosy living room and boasts an electric fire and accommodates a 3 piece suite. Leading off the living room is a well placed conservatory that looks over the stunning views and the well maintained garden. To the side of the living room is a door that leads to a ready made office space with plenty of wall storage and work space. Off this room is the second of the double bedrooms that also benefits for a large window that lets in plenty of natural light. This bedroom has an ensuite shower room with a WC and sink and would make a perfect guest bedroom. Moving on through the house to the kitchen, this is well appointed with plenty of room for a large dining table and plentiful storage with wall and floor units. To the rear of the kitchen is a large window that looks out on the large utility room that lets in natural light and has plenty of room for all kitchen white goods. -

Renewal of Planning Permission 08/00495/FULLO)

Agenda THE HIGHLAND COUNCIL 6.1 Item SOUTH PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE Report No PLS/058/15 18 August 2015 15/01099/FUL: Mr and Mrs K Smith Land 60M South East of Auchindarroch Farm, Duror, Appin Report by Area Planning Manager - South SUMMARY Description: Erection of dwelling house (Renewal of planning permission 08/00495/FULLO). Recommendation - GRANT Ward : 22 - Fort William and Ardnamurchan Development category : Local Pre-determination hearing : Not required Reason referred to Committee : Community Council objection. 1. PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT 1.1 It is proposed to erect a one and three quarter storey, four bedroom house on the eastern periphery of the village of Duror. The house is predominantly rectangular in footprint, with a garage projection on the south elevation. The house has a pitched roof which extends lower towards the front elevation. The roof is higher over the garage section, than the main house. External finishes have not been specified, however the plans imply a slate roof and vertical timber clad external walls. 1.2 No formal pre-application required. 1.3 The site is to be accessed from the existing private track off the Achindarroch public road which currently extends to the east past 'Glen Duror House' and to 'Achnacraig' at the end. A private septic tank and soakaway are proposed to treat foul drainage and connection is proposed to the public water main. 1.4 No supporting documents submitted. 1.5 Variations: None 2. SITE DESCRIPTION 2.1 The application site is an open area of rough grazing. The site is bordered by undeveloped land to the north and south. -

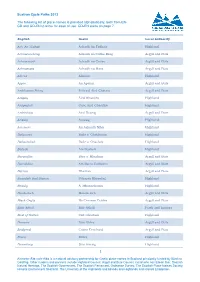

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise. -

Strategic Plan North Argyll Forests

Land Management Plan Brief - West Region Strategic Plan: North Argyll Forests (Brecklet, Glenachulish, Duror, Bealach, Appin, Creran) Date: 20/11/19 Planning Team: Mandie Currie, Chris Tracey, Philippa McKee John Taylor, Henry Dobson, Stuart Findlay Alastair Cumming, Jeff Hancox, Franco Giannotti, Kelly McKeller, Sergey Eydelman, James Robins, Jim Mackintosh Purpose The purpose of the Strategic plan for the forests of North Argyll is: To provide an overview of the large contiguous area of forest and open hill land managed by Forestry and Land Scotland (FLS) To set the development of the individual land management plans (LMP) in their wider landscape and management context To identify issues and themes that are common to several or all of the LMPs, set out the principles for managing these and where appropriate set out priorities for management between the different LMPs To prepare strategies for aspects of management that cover several or all the LMPs e.g. deer management and open habitat management Introduction Six forests in the northern part of the historic county of Argyllshire – Brecklet, Glenachullish, Duror, Bealach, Appin and Creran – comprise part of Scotland’s National Forests and Land (NFL) owned by Scottish Ministers on behalf of the Scottish people. Creran and Appin lie within Argyll and Bute, while the other forests are in the Highland Council administrative area. The six forests are linked by a large expanse of open hill ground, most of which is NFL. A strategic approach has been adopted to address the many issues in common and the various factors that impact across the entire land holding. -

7-Night Scottish Highlands Gentle Guided Walking Holiday

7-night Scottish Highlands Gentle Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Gentle Walks Destinations: Scottish Highlands & Scotland Trip code: LLBEW-7 1, 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Glen Coe is arguably one of the most celebrated glens in the world with its volcanic origins, and its dramatic landscapes offering breathtaking scenery – magnificent peaks, ridges and stunning seascapes. This easier variation of our best-selling Guided Walking holidays is the perfect way to enjoy a gentle exploration of the Scottish Highlands. Easy walks of 3-4 miles with up to 400 feet of ascent are available, although if you’d like to do something a bit more demanding walks up some of the lower hills are also included in the programme. Our medium option walks are 6 to 8 miles with up to 1000 feet of ascent whilst harder options are 8 to 10 miles with up to 2,600 feet of ascent. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our Country House • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Discover the dramatic scenery of the Scottish Highlands • Explore the atmospheric glens and coastal paths seeking out the best viewpoints. • Hear about the turbulent history of the highlands • Join our friendly and knowledgeable guides who will bring this stunning landscape to life TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 1, 2 and 3. This easier variation of our best-selling Guided Walking holidays is the perfect way to enjoy a gentle exploration of the Scottish Highlands. -

Mid Argyll, Kintyre and Islay

Weekly Planning list for 25 July 2014 Page 1 Argyll and Bute Council Planning Weekly List of Valid Planning Applications Week ending 25 July 2014 25/7/2014 9:28 Weekly Planning list for 25 July 2014 Page 2 Bute and Cowal Reference: 14/01486/PP Officer: StevenGove Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 20 - Isle Of Bute Community Council: Bute Community Council Proposal: Change of use from shop to office Location: 6Bridgend Street, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute, PA20 0HU Applicant: Mr Martin Robertson Netherfield , School Road, Romsey, SO51 7NY Ag ent: N/A Development Type: 04B - Business and Industry-Local Grid Ref: 208608 - 664661 Reference: 14/01719/PPP Officer: Br ian Close Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 20 - Dunoon Community Council: South CowalCommunity Council Proposal: Renewalofplanning permission 08/00400/OUT (Erection of dwellinghouse and for mation of vehicular access). Location: Plot 3, Ground North East Of Ashgrove , Wyndham Road, Innel- lan Applicant: Mar y Kohls Ashbank Cottage,Trinity Lane,Innellan, Dunoon, PA23 7TS Ag ent: N/A Development Type: 03B - Housing - Local Grid Ref: 214905 - 670477 Reference: 14/01741/LIB Officer: StevenGove Telephone: 01546 605518 Ward Details: 20 - Isle Of Bute Community Council: Bute Community Council Proposal: Formation of vehicular access,tur ning area and re-positioning of gate posts Location: Orcadia, 28 Craigmore Road, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute,PA20 9LB Applicant: Mrs Susan Brooks Orcadia, 28 Craigmore Road, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,Argyll And Bute,PA20 9LB Ag ent: James Wilson 7Chapelhill Road, Rothesay, Isle Of Bute,PA20 0BJ Development Type: 14 - Listed bldg. -

Auchindarroch Cottage Achindarroch, Duror, Appin

AUCHINDARROCH COTTAGE ACHINDARROCH DUROR APPIN PA38 4BS HOME REPORT Services provided by DM Hall include: • Architectural Planning and Drawing • Building Regulation Reports • Building Surveying • Business Appraisal, Valuation and Sales • Commercial Agency - Sales, Lettings and Acquisitions • Commercial Property Valuation and Appraisal • Energy Performance Certificates - Domestic and Non-domestic • Property Enquiry Certificates and Legal Searches • Property Management • Rating • Rent Reviews • Residential Development Appraisals For more information on any of the above services please visit us at www.dmhall.co.uk or phone 0 13 1 477 6000 Energy Performance Certificate Single Survey Single Survey survey report on: Property address AUCHINDARROCH COTTAGE ACHINDARROCH DUROR APPIN PA38 4BS Customer Mr Ian Reid and Miss Gereth Hood Customer address Achindarroch Cottage Achindarroch Duror Appin PA38 4BS Prepared by DM Hall LLP Date of inspection 1st June 2016 AUCHINDARROCH COTTAGE, ACHINDARROCH, DUROR, APPIN, PA38 4BS 1st June 2016 HP455749 Terms and Conditions PART 1 - GENERAL 1.1 THE SURVEYORS The Seller has engaged the Surveyors to provide the Single Survey Report and a generic Mortgage Valuation Report for Lending Purposes. The Seller has also engaged the Surveyors to provide an Energy Report in the format prescribed by the accredited Energy Company. The Surveyors are authorised to provide a transcript or retype of the generic Mortgage Valuation Report on to Lender specific pro-forma. Transcript reports are commonly requested by Brokers and Lenders. The transcript report will be in the format required by the Lender but will contain the same information, inspection date and valuation figure as the generic Mortgage Valuation Report and the Single Survey. The Surveyors will decline any transcript request which requires the provision of information additional to the information in the Report and the generic Mortgage Valuation Report until the Seller has conditionally accepted an offer to purchase made in writing. -

144 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

144 bus time schedule & line map 144 Fort William View In Website Mode The 144 bus line (Fort William) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Fort William: 3:50 PM (2) Kinlochleven: 7:05 AM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 144 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 144 bus arriving. Direction: Fort William 144 bus Time Schedule 29 stops Fort William Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 3:50 PM High School, Kinlochleven Riverside Road, Kinlochmore Tuesday 3:50 PM Post O∆ce, Kinlochleven Wednesday 3:50 PM Junction, Glencoe Thursday 3:50 PM Lorn Drive, Scotland Friday 1:30 PM Tourist Information, Ballachulish Saturday Not Operational Ballachulish Square, Ballachulish Maccoll Terrace, Ballachulish 144 bus Info Ballachulish Bridge, Ballachulish Direction: Fort William Stops: 29 Hotel, Ballachulish Trip Duration: 90 min Line Summary: High School, Kinlochleven, Post Glen Achulish Junction, Ballachulish O∆ce, Kinlochleven, Junction, Glencoe, Tourist Information, Ballachulish, Ballachulish Square, Ballachulish, Maccoll Terrace, Ballachulish, Holly Tree Hotel, Kentallen Ballachulish Bridge, Ballachulish, Hotel, Ballachulish, U5077, United Kingdom Glen Achulish Junction, Ballachulish, Holly Tree Hotel, Kentallen, Saint Adamnan's Church, Duror, Saint Adamnan's Church, Duror Stewart Hotel Road End, Duror, Dalnatrat Road End, Duror, Dalnatrat Road End, Duror, Duror Hotel, Duror, Stewart Hotel Road End, Duror Holly Tree Hotel, Kentallen, Kinlochleven Road End, North Ballachulish, -

West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Plana Leasachaidh Ionadail Na Gàidhealtachd an Iar Agus Nan Eilean

West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan Plana Leasachaidh Ionadail na Gàidhealtachd an Iar agus nan Eilean Adopted Plan September 2019 www.highland.gov.uk How to Find Out More | Mar a Gheibhear Tuilleadh Fiosrachaidh How to Find Out More This document is about future development in the West Highland and Islands area, including a vision and spatial strategy, and identified development sites and priorities for the main settlements. If you cannot access the online version please contact the Development Plans Team via [email protected] or 01349 886608 and we will advise on an alternative method for you to read the Plan. (1) Further information is available via the Council's website . What is the Plan? The West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan (abbreviated to WestPlan) is the third of three new area local development plans that, along with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and Supplementary Guidance, forms "the development plan" that guides future development in the Highlands. WestPlan focuses on where development should and should not occur in the West Highland and Islands area over the next 20 years. In preparing this Plan, The Highland Council have held various consultations firstly with a "Call for Sites" followed by a Main Issues Report then an Additional Sites Consultation followed by a Proposed Plan. The comments submitted during these stages have helped us finalise this Plan. This is the Adopted Plan and is now part of the statutory "development plan" for this area. 1 http://highland.gov.uk/whildp Adopted WestPlan The Highland Council 1 How to Find Out More | Mar a Gheibhear Tuilleadh Fiosrachaidh What is its Status? This Plan is an important material consideration in the determination of planning applications. -

Plot 2 with Croftland, Lettershuna, Appin Situated in a Quiet Setting on the Coast of Appin, a Picturesque Village Midway Between Oban and Ballachulish

38 High Street Fort William PH33 6AT Tel: 01397 703231 Fax: 01397 705070 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.solicitors-scotland.com Plot 2 with Croftland, Lettershuna, Appin Situated in a quiet setting on the coast of Appin, a picturesque village midway between Oban and Ballachulish. Bounded to the west by Loch Linnhe, with Loch Creran situated further south and enjoying stunning seascapes with rugged and mountainous inland scenery. This beautiful spot overlooks Loch Linnhe and is a short drive to one of Scotland’s iconic ruined castles, Castle Stalker, which occupies one of the tiny surrounding rock island. Stunning views over Loch Linnhe and the surrounding hills Croftland included, extending to 1.61 ha (3.98 acres or thereby) Plot extending 0.114 ha (0.28 acre) Planning in Principal for a 1½ story detached property PRICE GUIDE PLOT 2 £120,000 Situated in a quiet, setting on the coast of Appin, a picturesque village on a secluded peninsula midway between Oban and Ballachulish. Bounded to the west by Loch Linnhe, and enjoying stunning seascapes with rugged and mountainous inland scenery. This picturesque spot over looks Loch Linnhe and has stunning mountain scenery beyond. One of Scotland’s iconic ruined castles, Castle Stalker, occupies one of the tiny rock island and is only a few minutes’ drive from the plot. Appin is a semi-rural village location yet within easy reach of local amenities to include cafes, restaurants with bar and touring/camping park. This is an established and vibrant community, many of whom support and engage in various activities at the local Community Hall to include regular coffee mornings, bowls and a community choir. -

West Highland Centre of Mission

A Priest in Charge/Ordained Lead Evangelist To lead the West Highland Centre of Mission Feb 2017 A partnership between the Scottish Episcopal Church Diocese of Argyll and The Isles and Church Army Overview This profile presents an exciting ministry in the Scottish Episcopal Church, rooted in the beautiful context of the West Highlands of Scotland, a popular tourism and outdoor pursuit area. A priest in charge/ordained evangelist is needed to be the lead evangelist of the new Centre of Mission in the diocese of Argyll and The Isles, located in the West Highlands area. This is a partnership between the diocese and Church Army. The lead evangelist will be involved in appointing a pioneer evangelist as the project starts, and this pioneer will report to the lead evangelist. This profile contains some information about this additional role. The Priest in Charge/Lead Evangelist will support the worshipping and spiritual life of the existing charges with a sustainable pattern of worship. They will also work with the vestries of the charges as they make a transition to a simpler structure for management and worship of the church in this area. The Priest in Charge/Lead Evangelist will develop the lay teams of these communities and, working alongside the pioneer evangelist and the diocese, lead these churches into growth. This ministry at present covers the existing church communities, each with a different context and history, but with a history of shared ministry. The clergy accommodation is in Glencoe, a central geographical location to the area. Each of the church communities is shown as a blue marker on the map below, and is described in more detail in this profile.