View of Ofakim; in the Background: Of-Ar Textile Factory, 1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emergency in Israel

Emergency in Israel Emergency Update on Jewish Agency Programming May 16, 2021 The recent violent events that have erupted across the country have left us all surprised and stunned: clashes with Palestinians in Jerusalem and on the Temple Mount; the deteriorating security tensions and the massive barrage of missiles from Gaza on southern and central Israel; and the outbreak of unprecedented violence, destruction, and lynching in mixed cities and Arab communities. To say that the situation is particularly challenging is an understatement. We must all deal with the consequences of the current tensions. Many of us are protecting family, coworkers, or people under our charge while missiles fall on our heads night and day, forcing us to seek shelter. We have all witnessed the unbearable sights of rioting, beating, and arson by Arab and Jewish extremists in Lod, Ramla, Acre, Kfar Qassem, Bat Yam, Holon, and other places. As an organization that has experienced hard times of war and destruction, as well as periods of prosperity and peace, it is our duty to rise up and make a clear statement: we will support and assist populations hit by missile fire as we did in the past, after the Second Lebanon War and after Operations Cast Lead and Protective Edge. Together with our partners, we will mobilize to heal and support the communities and populations affected by the fighting. Our Fund for Victims of Terror is already providing assistance to bereaved families. When the situation allows it, we will provide more extensive assistance to localities and communities that have suffered damage and casualties. -

Global Connections Israel, Greater Metrowest, and the World

ופרצת U’faratzta Global Connections Israel, Greater MetroWest, and the World Introduction After much consideration, we would like to present a draft plan to restructure the Israel Center of Greater MetroWest. This plan was developed based on feedback from our community members, and a feeling that, in a changing world, we need to be proactive, creative, and innovative. There are four goals for this restructure: To streamline the Israel Center committees and subcommittees, and foster collaboration between related activities To create a mentoring mechanism that will allow us to develop new emerging activists, establishing a leadership development pipeline. To provide a smooth and rational transition into the new allocations system emerging from the Federation strategic plan To create a fresh, exciting, and clear way to tell our story based on Jewish sources 1 The Story of Our People and Our Community Jacob, our forefather, in his dream, sees angels ascending and descending the stairway, the bottom resting on the earth and the top reaching heaven. In the midst of the dream, God tells him that his descendants will be like the dust of the earth, spreading out over the north, south, east, and west. "ופרצת ימה וקדמה, צפונה ונגבה“ “U’faratza yama v’kedma, tsafona v’negba” (Genesis 28:14) There, in Biblical Bethel, where Jacob’s name is changed to Israel, and where our nation is formalized, we are blessed with the promise to multiply, break through, and scatter. The promise does not draw borders or impose geographic limits; it only directs the people to the four corners of the Earth. -

PM Netanyahu and Quartet Rep Blair Announce Economic Steps to Assist

Arabs, Jews to travel to Poland together Special delegation of Jewish, Arab, Druze, Bedouin and Christian students to visit concentration camps, learn about 'the other.' 'We're leaving as a united group of friends,' one student says Tomer Velmer A unique group consisting of 220 Jewish, Arab, Druze, Bedouin and Christians teenagers is expected to visit Nazi concentration camps in Poland later this month. The participants are all students at Amal high schools across Israel. The trip will be held under the banner, "We are all part of same human fabric." Amal Group Director Shimon Cohen wrote a letter to the students, asking them to bring with them on their journey not just food and clothing but also patience, openness and attentiveness. The group decided to allow the students to experience both the suffering the Jewish people have gone through and the pain caused to other nations and religions in an attempt to acknowledge "the other". Preparing for the journey (Photo: Sami Kara) Many Amal schools are taking part in the special mission, including those in Shefaram, Rahat, Dimona, Hadera, Ofakim, and Kiryat Malakhi. Each student will pay roughly NIS 5,000 ($1,360) for the trip, part of which will be subsidized by Amal and the Education Ministry. Throughout their visit, the students will be divided into integrated groups consisting of Arab, Hebrew and English speakers. One big united group In preparation for their trip the students participated in a series of meetings aimed at connecting the different worlds they all come from. "The first few meetings were awkward for them due to cultural differences, and the fact that not all of them speak Hebrew," the project manager said. -

Polio October 2014

Europe’s journal on infectious disease epidemiology, prevention and control Special edition: Polio October 2014 Featuring • The polio eradication end game: what it means for Europe • Molecular epidemiology of silent introduction and sustained transmission of wild poliovirus type 1, Israel, 2013 • The 2010 outbreak of poliomyelitis in Tajikistan: epidemiology and lessons learnt www.eurosurveillance.org Editorial team Editorial advisors Based at the European Centre for Albania: Alban Ylli, Tirana Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Austria: Reinhild Strauss, Vienna 171 83 Stockholm, Sweden Belgium: Koen De Schrijver, Antwerp Telephone number Belgium: Sophie Quoilin, Brussels +46 (0)8 58 60 11 38 Bosnia and Herzogovina: Nina Rodić Vukmir, Banja Luka E-mail Bulgaria: Mira Kojouharova, Sofia [email protected] Croatia: Sanja Musić Milanović, Zagreb Cyprus: to be nominated Editor-in-chief Czech Republic: Bohumir Križ, Prague Ines Steffens Denmark: Peter Henrik Andersen, Copenhagen Senior editor Estonia: Kuulo Kutsar, Tallinn Kathrin Hagmaier Finland: Outi Lyytikäinen, Helsinki France: Judith Benrekassa, Paris Scientific editors Germany: Jamela Seedat, Berlin Karen Wilson Greece: Rengina Vorou, Athens Williamina Wilson Hungary: Ágnes Csohán, Budapest Assistant editors Iceland: Haraldur Briem, Reykjavik Alina Buzdugan Ireland: Lelia Thornton, Dublin Ingela Söderlund Italy: Paola De Castro, Rome Associate editors Kosovo under UN Security Council Resolution 1244: Lul Raka, Pristina Andrea Ammon, Stockholm, Sweden Latvia: Jurijs Perevoščikovs, -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

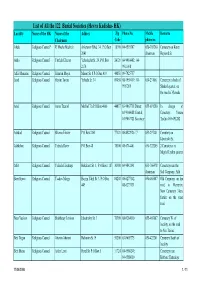

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Segmenting the Naqab (Negev): Israel Redistricts to Postpone Local Elections for Arab-Bedouin Citizens

Adalah’s Newsletter, Volume 97, October 2012 Segmenting the Naqab (Negev): Israel Redistricts to Postpone Local Elections for Arab-Bedouin Citizens Dr. Thabet Abu Ras Director of Adalah’s Naqab Office Introduction: The Interior Ministry Scrambles to Block Elections in Abu Basma Jewish Regional Councils in the Naqab cover 86% of the Naqab (Negev), 11,600 square kilometers (km2) of the Naqab’s 12,835km2, and include most of the Naqab’s tax revenue- generating operations. The eight Arab local authorities of the Naqab, including the government- appointed Abu Basma Regional Council, which has Arab constituents but Jewish leadership, oversee only 120km2, or 1% of the Naqab. Arab-Bedouin constitute one-third of the population of the Naqab (Source: Negev Statistical Yearbook, 2006). First-time elections for the Abu Basma Regional Council in 2012 would make it more difficult for the Israeli government to implement the Prawer Plan, the scheme to ‘regulate Bedouin settlement’ over the next five years and forcibly displace up to 70,000 Bedouin in the Naqab. The government founded the Abu Basma Regional Council in 2003 to oversee 10 newly recognized Bedouin villages, and promptly appointed members to the Council, delaying elections multiple times. In 2010, the Supreme Court mandated that the Council hold elections by December 2012 in a case brought by Adalah and the Association for Civil Rights in Israel against the government. A democratically-elected Abu Basma Regional Council that represents its 25,000 constituents would complicate the government’s planning and enforcement of the Prawer Plan. Therefore, the Israeli Interior Ministry scrambled to deal with the Supreme Court’s decision and delay elections again. -

Israel 2019 Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS National Review ISRAEL 2019 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Acknowledgments are due to representatives of government ministries and agencies as well as many others from a variety of organizations, for their essential contributions to each chapter of this book. Many of these bodies are specifically cited within the relevant parts of this report. The inter-ministerial task force under the guidance of Ambassador Yacov Hadas-Handelsman, Israel’s Special Envoy for Sustainability and Climate Change of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Galit Cohen, Senior Deputy Director General for Planning, Policy and Strategy of the Ministry of Environmental Protection, provided invaluable input and support throughout the process. Special thanks are due to Tzruya Calvão Chebach of Mentes Visíveis, Beth-Eden Kite of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Amit Yagur-Kroll of the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Ayelet Rosen of the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Shoshana Gabbay for compiling and editing this report and to Ziv Rotshtein of the Ministry of Environmental Protection for editorial assistance. 3 FOREWORD The international community is at a crossroads of countries. Moreover, our experience in overcoming historical proportions. The world is experiencing resource scarcity is becoming more relevant to an extreme challenges, not only climate change, but ever-increasing circle of climate change affected many social and economic upheavals to which only areas of the world. Our cooperation with countries ambitious and concerted efforts by all countries worldwide is given broad expression in our VNR, can provide appropriate responses. The vision is much of it carried out by Israel’s International clear. -

List of Higher Education Institutions Applicable for Financial Aid As Recognized by the Student Authority

List of Higher Education Institutions applicable for financial aid as recognized by the Student Authority: Universities: ● Ariel University, Shomron ● Bar Ilan University ● Ben Gurion University of the Negev and Eilat Campus ● Haifa University ● Hebrew University of Jerusalem ● Open University of Israel ● Technion- Israel Institution of Technology, Haifa ● Tel Aviv University ● Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot Colleges and Academic Institutions: ● Achva Academic College, Kiryat Malachi ● Ashkelon Academic College ● Western Galilee College, near Akko city ● Hadassah Academic College, Jerusalem ● Kinneret Academic College, Jordan Valley ● Sapir Academic College, near Sderot ● Max Stern Academic College of Emek Yezreel, near Afula ● Zefat Academic College ● Tel Aviv – Yaffo Academic College ● Tel-Hai Academic College ● Ruppin Academic Center, near Netanya Colleges and Institutions of Higher Education in the Fields of Science, Engineering and, Liberal Arts: ● Afeka – Tel Aviv Academic College of Engineering ● Jerusalem College of Technology- Lev Academy Center ● Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem ● The Jerusalem (Rubin) Academy of Music and Dance ● The Braude ORT College of Technology, Karmiel ● Azrieli College of Engineering, Jerusalem ● Sami Shamoon College of Engineering, Beer Sheva and Ashdod Campus ● Shenkar College of Textile Technology and Fashion, Tel Aviv ● The Holon Center for Technology Studies Institutions of Higher Education Recognized by the Student Authority, not subsidized by the Israeli Government *These Institutions are recognized by the Committee of Higher Education, and are recognized for financial aid by the Student Authority. *Tuition Cost for the following institutions is higher than 25,000-35,000 Shekels a year. *The Student Authority provides financial aid equivalent to regularly subsidized tuition costs of 11,000 Shekels yearly for Undergraduate Degree and, 13,700 Shekels for Master's Degree. -

Assessment of Land Use Change Impact on Ecohydrological Parameters Using Remote Sensing in the Sub-Catchments of the Patish Watershed, Israel

Assessment of Land Use Change Impact on Ecohydrological Parameters Using Remote Sensing in the Sub-Catchments of the Patish Watershed, Israel MSc Thesis by Bart de Jong August 2012 i | P a g e Assessment of Land Use Change Impact on Ecohydrological Parameters Using Remote Sensing in the Sub-Catchments of the Patish Watershed, Israel Master thesis Land Degradation and Development Group submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Science in International Land and Water Management at Wageningen University, the Netherlands Study program: MSc International Land and Water Management (MIL) Student registration number: 860205-401-120 LDD 80336 Supervisors: Dr. Eli Argaman1 Dr. Saskia Keesstra2 Dr. Naftali Goldshleger1 Examinator: Dr. ir. M.J.P.M. Riksen, Dr. S.D. Keesstra Date: August 2012 1 Soil Erosion Research Station, Ministry of Agriculture, Israel 2 Wageningen University, Land Degradation and Development Group ii | P a g e Abstract De Jong, B. 2012. Assessment of Land Use Change Impact on Ecohydrological Parameters Using Remote Sensing in the Sub-Catchments of the Patish Watershed, Israel. MSc. Thesis. Land Degradation and Development Group, Wageningen University. Discharge measurements in the Patish watershed in the Northern Negev region in Israel show a low stream flow, which cannot be explained by hydrological modelling. One hypothesis is that low discharge is caused by changes in land use in the watershed, which influence the rainfall/runoff ratio. This hypothesis was tested by assessing the impact of land use change on Ecohydrological parameters. Change in land use is determined by analysing Landsat images using Definiens®. Soil Ecohydrological properties were derived by field experiments, and taking samples to be analysed in the laboratory. -

Organization Chart R

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file, please contact us at NCJRS.gov. 'I II! , ,i, -----------------"-"- ANNUAL REPORT ISRAEL POLICE CONTENTS The Inspector General's Letter to the Minister of the Interior 3 Criminal Activity 5 Investigation and Intelligence Work 7 Juvenile Delinquency 8 Criminal Identification 9 Internal Security 11 Road Traffic 13 Patrol 14 Research and Development 15 Training 16 Administration 17 Manpower 18 The Computer Unit 20 Legal Assistance 21 Public Complaints ami the Internal Comptroller 22 24 Spokesman's Office International Contacts 25 Statistical Tables 26 Organization Chart r.. n S~rrJ ~ "'=> tdJ r.~li. ~ ~ .• Published by The Israel Police, Training Division, Publication Unit Printed at Hamakor Press, Jerusalem 1978 The Minister of the Interior, Jerusalem. Sir, I have the honour to submit to you the annual report on the work of the {sraeli police for 1977. This report will reflect criminal and internal security events in the past year, and the manner in which the police dealt with them. More than ever before. this year was marked by close public interest in crime and police activity - an interest which found its principal expres sion in the creation of two commissions of inquiry: the Buchner Commis sion and the Shimron Commission. Not always taking a favourable form. thi~ interest confronted the police with numerous challenges. The first and most important of these was a puncfillious re-examination of organisa tional structures and concepts. In retrospect, the public outcry relating to the Israeli police did not find it in a state of intellectual stagnation. On the contrary.