Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ho Li Day Se Asons and Va Ca Tions Fei Er Tag Und Be Triebs Fe Rien BEAR FAMILY Will Be on Christmas Ho Li Days from Vom 23

Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 12. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 12th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 12. Janu ar 2004 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken day 12th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - wir uns für die gute Zusam menar beit im ver gange nen mers for their co-opera ti on in 2003. It has been a Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY...............................2 BEAT, 60s/70s.........................66 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. ........................19 SURF ........................................73 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER ..................22 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY .......................75 WESTERN .....................................27 BRITISH R&R ...................................80 C&W SOUNDTRACKS............................28 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT ........................80 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS ......................28 COUNTRY AUSTRALIA/NEW ZEALAND ...............29 POP ......................................82 COUNTRY DEUTSCHLAND/EUROPE .................30 POP INSTRUMENTAL ............................90 -

January 2016

THE GRANNYTOWN GAZETTE The Newsletter of the Alden Historical Society, Alden NY 14004 Published Quarterly [email protected] January 2016 MISSION STATEMENT The Alden Historical Society, founded in 1965, is a volunteer-supported organization whose mission is to preserve, promote and present the history of the Town of Alden and its people. One Name on the Wall Engraved on the face of the new Alden Veterans Memorial (designed by our own Conrad Borucki) are the names of seventy-one men who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country from Moses Fenno in the War of 1812 to Brett Gornewicz in Afghanistan in 2012. Each of those names is a son, a brother, a husband or a father. This is the story of one of those. was asked by Supervisor Milligan and the we searched census listings, service listings, Memorial Committee to help verify the names on service honor rolls, to no avail. The committee I a list they had been given. Judy Hotchkin was decided to keep his name on the list with the hope already at work on the list, primarily with the World we could learn about him. Then, in the July 23, War II and Viet Nam War names. I had done 2015, issue of the Alden Advertiser, Lee research on Alden’s Civil War men so I started Weisbeck reprinted the front page of the July 23, there. Judy and I discovered some misspellings, a 1949, issue. There, near the bottom of the first man listed in the wrong war, some not from Alden, column, was an article “Lt. -

America the Beautiful Part 2

America the Beautiful Part 2 Charlene Notgrass 1 America the Beautiful Part 2 by Charlene Notgrass ISBN 978-1-60999-142-5 Copyright © 2021 Notgrass History. All rights reserved. All product names, brands, and other trademarks mentioned or pictured in this book are used for educational purposes only. No association with or endorsement by the owners of the trademarks is intended. Each trademark remains the property of its respective owner. Unless otherwise noted, scripture quotations are taken from the New American Standard Bible®, Copyright © 1960, 1962, 1963, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Cover Images: Statue of Liberty by Mihai_Andritoiu / Shutterstock.com; Immigrants and Trunk courtesy Library of Congress Back Cover Author Photo: Professional Portraits by Kevin Wimpy The image on the preceding page is of the Pacific Ocean near the Channel Islands. No part of this material may be reproduced without permission from the publisher. You may not photocopy this book. If you need additional copies for children in your family or for students in your group or classroom, contact Notgrass History to order them. Printed in the United States of America. Notgrass History Gainesboro, TN 1-800-211-8793 notgrass.com Aspens in Colorado America the Beautiful Part 2 Unit 16: Small Homesteads and Big Businesses ............... 567 Lesson 76 - Our American Story: Reformers and Inventors .....................................................568 19th President Rutherford B. Hayes .......................................................................................575 -

God Bless America

www.singalongwithsusieq.com The Star-Spangled Banner Oh, say, can you see By the dawn's early light What so proudly we hailed At the twilight's last gleaming? Whose broad stripes and bright stars Through the perilous fight O'er the ramparts we watched Were so gallantly streaming. And the rockets' red glare The bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night That our flag was still there. O say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave. 2 America the Beautiful O beautiful for spacious skies For amber waves of grain For purple mountain majesties Above thy fruited plain! America! America! God shed His grace on thee And crown thy good with brotherhood From sea to shining sea! O beautiful for pilgrim’s feet Whose stern impassioned stress A thoroughfare of freedom beat Across the wilderness! America! America! God mend thine every flaw Confirm thy soul in self-control Thy liberty in law! O beautiful for heroes proved In liberating strife Who more than self their country loved And mercy more than life! America! America! May God thy gold refine Till all success be nobleness And every gain divine! 3 O beautiful for patriot dream That sees beyond the years Thine alabaster cities gleam Undimmed by human tears! America! America! God shed His grace on thee And crown thy good with brotherhood From sea to shining sea! Repeat last 4 lines 4 You’re A Grand Old Flag You're a grand old flag You're a high-flying flag And forever in peace may you wave You're the emblem of The land I love The home of the free and the brave Every heart beats true Under red, white and blue Where there's never a boast or brag But should old acquaintance be forgot Keep your eye on the grand old flag. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

War of the Words Thesis on the Representation of The

War of the Words Thesis on the representation of the Islamic State by the Obama administration Frank Kleef University of Amsterdam Supervisor: dhr. prof. dr. R.V.A. (Ruud) Janssens Student no.: 10547045 20-06-2017 Abstract The Obama administration used a strategy that actively sought to delegitimize the enemy in order to pursue its efforts to counter the Islamic State and portrayed it as a manifestation of evil. In this thesis I intend to argue that by representing the effort to degrade and ultimately destroy the Islamic State as a conflict between freedom and evil, the Obama administration utilized a very idealistic rhetorical framework. Problematically, the approach taken by the Obama administration to counter the Islamic State really had more to do with the United States itself than the Islamic State, the alleged object of the conflict. Although Obama was frequently lauded for deviating from the rhetorical idealism of the Bush administration, analysis shows that the rhetoric of the Obama administration only changed in style rather than in substance. This thesis aims to contribute to the current academic discourse considering the general reflection on the Obama administration. More specifically, about its Middle East policy and its comprehensive effort to counter the Islamic State. Consequently, it remarks on the problematic approach with which the Obama administration sought to react to the situation in the Middle East and the Islamic State. By doing so, I intend to contribute to the understanding of the Western discourse in order -

PISD Graduation Rate Reaches 89 Percent Can Pay an Additional $30

Voice of Community-Minded People since 1976 August 28, 2014 Email: [email protected] www.southbeltleader.com Vol. 39, No. 30 SB Girls Softball registers South Belt Girls Softball fall registration is $25 plus the candy fundraiser (one box of can- dy - $25). Those who do not wish to fundraise PISD graduation rate reaches 89 percent can pay an additional $30. The graduation rate in Pasadena Independent result of improvements in the curriculum and pus that provided students with fl exible learning currently enroll in classes through San Jacinto For more information, visit www.eteamz. School District has reached new heights, with programs offered throughout the district. options. For instance, the Community School al- College. This gives each student the opportunity com/southbeltgirls. The last day set for fall 89 percent of high school seniors in the district “Our kids are graduating at a higher rate be- lows students, 18 years and older, who are a few to earn an associate degree by the time he or she registration is Thursday, Aug. 28, from 6 to 8 graduating in 2013. That fi gure represents a 22 cause teachers and staff at every grade level be- credits shy of graduating an opportunity to earn earns a high school diploma. The fi rst cohort of p.m. percent increase since 2005. gan introducing new rigor into the education of a diploma. Tegler Career Center offers smaller Pasadena High School students will graduate The Texas Education Agency recently re- our children eight years ago that better equipped class sizes so students receive one-on-one in- from this program in May 2015. -

Old Glory, a Symbol of Freedom

THE PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE I remember this one teacher. To me, he was the greatest teacher, a real sage of my time. He had much wisdom. We were all reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, and he walked over. Mr. Lasswell was his name … He said: “I’ve been listening to you boys and girls recite the Pledge of Allegiance all semester and it seems as though it is becoming monotonous to you. If I may, may I recite it and try to explain to you the meaning of each word. I – me, an individual, a committee of one. Pledge – dedicate all my worldly goods to give without self-pity. Allegiance – my love and my devotion. To the Flag – our standard, Old Glory, a symbol of freedom. Where ever she waves, there is respect because your loyalty has given her a dignity that shouts freedom is everybody’s job. Of the United – that means that we have all come together. States – individual communities that have united into 48 states, 48 individual communities with pride and dignity and purpose, all divided with imaginary boundaries, yet united to a common purpose, and that’s love of country. Of America And to the Republic – a state in which sovereign power is invested in representatives chosen by the people to govern. For which it stands One nation – meaning, so blessed by God. Indivisible – incapable of being divided. With liberty – which is freedom and the right of power to live one’s life without threats or fear or some sort of retaliation. And justice – The principle or quality of dealing fairly with others. -

2018Patternsonline

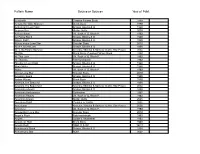

Pattern Name!!!!!Source or Sources!!!!Year of Publ. Acrobatik Creative Pattern Book 1999 Across the Wide Missouri Block Book 1998 Adirondack Log Cabin Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Aegean Sea Stellar Quilts 2009 African Safari Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 Air Force Block Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Album Patch Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Albuquerque Lone Star Singular Stars 2018 Alice's Adventures Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 All in the Family Sampler Knockout Blocks & Sampler Quilts, Star Power 2004 All Star Block Book, Creative Pattern Book 1998 All That Jazz Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 All Thumbs Patchworkbook 1983 Allegheny Log Cabin Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Alma Mater Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Aloha Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 Alpine Lone Star Singular Stars 2018 Amazing Grace Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Amber Waves Block Book 1998 America, the Beautiful Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 America, the Beautiful 2 Knockout Blocks & Sampler Quilts, Star Power 2004 American Abroad Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 American Ambassador Quiltmaker 1982 American Beauty Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 American Dream Stellar Quilts 2005 American Spirit Cookies 'n' Quilts 2001 Americana Knockout Blocks & Sampler Quilts, Star Power 2000 Amethyst Ult. Book of Q. Block P. 1988 Amsterdam Lone Star Singular Stars 2018 Angel's Flight Patchworkbook 1983 Angels Quilter’s Newsletter 1983 Angels on High Block Book 1998 Angels Quilt QNM, Q & OC 1981? Anniversary Block Scraps, Blocks & Q 1990 Anniversary Star BOM 2002 Pattern Name!!!!!Source or Sources!!!!Year of Publ. Anniversary Stars-45th Anniversary -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

The Evolution of the Theme of Race Relations in the United States: A

The Evolution of the Theme of Race Relations in the United States: A Rhetorical Analysis of “The Gettysburg Address,” “I Have a Dream,” and “A More Perfect Union.” A Senior Project Presented to The Faculty of the Communication Studies Department California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Bachelor of Arts By Matthew Schonfeld June 2011 Matthew Vincent Schonfeld Schonfeld 2 Table of Contents Introduction----------------------------------------------------------------3 King’s Background and Notable Accomplishments------------------5 “I Have a Dream”---------------------------------------------------------7 King’s Implementation of the Bible------------------------------------8 Voice Merging-------------------------------------------------------------10 King’s Allusion to Lincoln---------------------------------------------13 Final Moments of the Speech------------------------------------------15 “A More Perfect Union”------------------------------------------------18 Obama’s Use of Consilience and Prophetic Voice------------------18 “A More Perfect Union:” Similarities Between King & Obama--23 Conclusion----------------------------------------------------------------28 Works Cited--------------------------------------------------------------33 Schonfeld 3 Schonfeld 4 Introduction Few speeches in American history are as well known and iconic as Martin Luther King Jr.'s “I Have a Dream” speech. The speech is not just famous for its delivery but famous for its oration