Jackdaws Reach the New World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hooded and Carrion Crows to Be Members of the Same Species

ADVICE The conservation and legal status of the hooded crow in England 1. Background and legal status 1.1 Until 2002, hooded crow and carrion crow were considered to be separate races (sub-species) of the same species Corvus corone. Hooded crow and carrion crow were listed separately in the second schedule of the Protection of Birds Act (1954) which allowed both forms to be killed. Corvus corone (with the common name ‘Crow’) was included in Schedule 2 Part II of the Wildlife & Countryside Act (1981). This listed birds which could be killed or taken by authorised persons at all times and was colloquially referred to as the ‘pest bird’ list. Covus corone and all other species were removed from Schedule 2 Part II in 1993. Corvus corone (‘Crow’) was subsequently included on several general licences when these replaced Schedule 2 Part II as a mechanism for authorising control of named species in certain circumstances and under specified conditions. As sub-species of Corvus corone both hooded crow and carrion crow could be controlled under these licences. 1.2 Following a full review of the latest evidence, the British Ornithologists’ Union (BOU) recommended in 2002 that carrion crow and hooded crow be treated as separate species, Corvus corone and C. cornix respectively (Knox et al. 2002; Parkin et al. 2003). Following this taxonomic recommendation, both species were admitted to the official BOU list of British birds. 1.3 Since 2002, the general licences for England have continued to list Corvus corone (common name ‘Crow’). Due to the taxonomic change this has had the effect of limiting use of the licences to control of the carrion crow, which is the only form of the crow now regarded as Corvus corone. -

Crow Threat to Raptors?

PIED pirates CROW THREAT TO RAPTORS? There has been much debate about the effects on biodiversity of increasing Pied Crow and other corvid populations in Africa, but little has been quantified. It is evident from the latest bird atlas data that there are now more Pied Crows in southern Africa than there were a decade ago and that the species has spread into areas of the Karoo where it did not occur previously. But what effect is this having on other bird species? TEXT BY ROB SIMMONS & PHOEBE BARNARD ALBERT FRONEMAN arious reports indicate that one a Rock Kestrel and another a Southern crows are impacting negatively Pale Chanting Goshawk, all of which were on other creatures in their en- carrying mice in their talons. Prey-carrying vironment. Farmers complain raptors are usually provisioning dependent aboutV increasing predation by ‘crows’ on females or nestlings, so piracy affects more lambing ewes, birders suggest that more at- than simply the bird with the food. tacks are occurring on passerine birds, and The following three incidents serve to conservationists and members of the pub- highlight the modus operandi of the crows. lic report greater numbers of crows killing We then investigated other parts of Africa small tortoises. However, almost nothing to determine if piracy targeting raptors is has been quantified as to the level of such limited to western South Africa as a zone predation, the magnitude of the upsurge of Pied Crow range expansion or is a more in crow interactions and the effect on the widespread strategy. species being attacked. We do not yet have In the West Coast National Park in such data, but we do take a first look at 2008, our attention was drawn to a Black- what may be an increasing and somewhat shouldered Kite that was calling from a surprising addition to the negative effects height of over 150 metres and circling up- of crows – those on birds of prey. -

Tropical Birding Tour Report

Please click logo to visit our homepage Custom JAPAN : Cranes and winter specialties 20 - 25 March 2009 Leader: Keith Barnes All photos by Keith Barnes Custom tour Cranes, cranes, cranes – that is what Japan in winter is all about. This trip was a quickfire junket to the islands of Japan to nab the winter specialties. The clients had already done a Japan trip in summer and had spent considerable time in eastern Asia already, meaning that a few East Asia specialty birds like Black-faced Spoonbill and Baer’s Pochard were not target species. The group had also already seen almost all of the Japanese endemics and summer specialty birds. With so few days at our disposal, we visited only a few strategic birding sites on Kyushu (Arasaki) and Hokkaido (Kushiro, Lake Furen, Nemuro and Rausu) and finished off with a pelagic ferry trip returning to Honshu (Tomakomai – Ooarai). On this very short 5-and-a-half day trip we scored 110 species including all 22 target species that the clients asked me to design the trip around. March 20. Kagoshima to Arasaki We arrived in Kagoshima at midday, and shot straight up the east coast to a site known for its Japanese Murrelet. This bird, which can be quite a severe problem, was easy this time, with a handful bobbing about in the placid waters of the bay. No sooner had we seen the bird and we stared marking our way to Arasaki and the phenomenal crane reserve there. We arrived shortly after dark, but could hear the cacophony outside, with cranes bugling in the dark. -

Diet of the Steller's Sea Eagle in the Northern Sea of Okhotsk

First Symposium on Steller’s and White-tailed Sea Eagles in East Asia pp. 71-82, 2000 UETA, M. & MCGRADY, M.J. (eds) Wild Bird Society of Japan, Tokyo Japan Diet of the Steller’s Sea Eagle in the Northern Sea of Okhotsk Irina UTEKHINA1, Eugene POTAPOV2* & Michael J. MCGRADY3# 1. Magadan State Reserve, Portovaya str. 9, Magadan 685000, Russia. e-mail: [email protected] 2. Institute of Biological Problems of the North, Russian Academy of Sciences, Magadan 685000, Russia. 3. Raptor Research Center, Boise State University, 1910 University Drive, Boise, Idaho 83725-1516, USA. Abstract. Qualitative data on the diet of adult and young Steller’s Sea Eagles Haliaeetus pelagicus in North Okhotia during spring (incubation period) and summer (chick rearing period) have been analyzed. The total of 177 prey samples containing 551 prey items from nests located on rivers, seacoast and on islands with large sea bird colonies were analyzed. The diet of Steller’s Sea Eagles consists (in descending order of importance) of birds, fish, mammals, and carrion. Birds dominate the diet of the coastal pairs (73%, N = 107), especially in the pairs breeding at the sea bird colonies (91%, N = 211). The proportion of birds in the diet of eagles nesting on rivers is much lower (11%, N = 38). In summer fish is a dominant component of diet only in riparian pairs (77%, N = 78). In coastal pairs, as well as in pairs at the seabird colonies the proportion of fish was lower: 26% and 7% (N = 28 and 19) respectively. Carrion is very important for Steller’s Sea Eagles in spring. -

Japan in Winter

JAPAN IN WINTER JANUARY 19–31, 2019 Red-crowned Crane roost, Setsuri River, Tsurui, Hokkaido - Photo: Arne van Lamoen LEADERS: KAZ SHINODA & ARNE VAN LAMOEN LIST COMPILED BY: ARNE VAN LAMOEN VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM JAPAN IN WINTER: A CRANE & SEA-EAGLE SPECTACLE! By Arne van Lamoen For a trip as unique as VENT’s “Japan in Winter” tour, it is very difficult to reduce an eleven-day trip into a single, representative highlight. Moreover, to do so would be to eschew a great many other lifetime memories unlikely to be objectively less remarkable. I content myself here to a smattering then, in the interest of brevity, but as is so often the case when describing the beauty and majesty of nature—and birds in particular—mere words will not do these sightings justice. This tour featured several new life birds for even our most seasoned and almost impossibly well-traveled participants, Trent and Meta. I know that for them, the Japanese endemics (and near endemics) such as the Ryukyu Minivet sighted in Kyushu ( Pericrocotus tegimae ) and resident Red-crowned Cranes in Hokkaido ( Grus japonensis ) were among several trip highlights. For others, the inescapable grandeur and majesty of Steller’s Sea-Eagles ( Haliaeetus pelagicus ), both perched on snowy trees and overhead in flight, could not be denied. I count myself among them. Still others were enamored with the rare Baikal Teals ( Sibirionetta formosa ) spotted in a partially iced-over reservoir on Kyushu and the even (globally) rarer Black-faced Spoonbills ( Platalea minor ) and solitary Saunder’s Gull ( Chroicocephalus saundersi ) which we sighted not five minutes apart along the Hi River. -

Corvid Response to Human Settlements and Campgrounds: Causes, Consequences, and Challenges for Conservation

BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION 130 (2006) 301– 314 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Corvid response to human settlements and campgrounds: Causes, consequences, and challenges for conservation John M. Marzluff*, Erik Neatherlin Ecosystem Sciences Division, College of Forest Resources, University of Washington, Box 352100, Seattle, WA 98195-2100, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Human development often favors species adapted to human conditions with subsequent Received 14 August 2004 negative effects on sensitive species. This is occurring throughout the urbanizing world Received in revised form as increases by generalist omnivores, like some crows and ravens (corvids) threaten other 5 December 2005 birds with increased rates of nest predation. The process of corvid responses and their Accepted 20 December 2005 actual effects on other species is only vaguely understood, so we quantified the population Available online 9 February 2006 response of radio-tagged American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos), common ravens (Corvus corax), and Steller’s jays (Cyanocitta stelleri) to human settlements and campgrounds and Keywords: examined their influence as nest predators on simulated marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus Anthropogenic disturbance marmoratus) nests on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula from 1995 to 2000. The behavior and American crow demography of crows, ravens, and jays was correlated to varying degrees with proximity to Camping human development. Crows and ravens had smaller home ranges and higher reproduction Common raven near human settlements and recreation. Annual survival of crows was positively associ- Endangered species ated with proximity to human development. Home range and reproduction of Steller’s jays Home range was independent of proximity to human settlements and campgrounds. -

Great Spotted Cuckoo Nestlings Have No Antipredatory Effect on Magpie Or Carrion Crow Host Nests in Southern Spain

RESEARCH ARTICLE Great spotted cuckoo nestlings have no antipredatory effect on magpie or carrion crow host nests in southern Spain Manuel Soler1*, Liesbeth de Neve2, MarõÂa RoldaÂn1, TomaÂs PeÂrez-Contreras1, Juan Jose Soler3 1 Departamento de ZoologõÂa, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2 Dep. Biology, Terrestrial Ecology Unit, Ghent University, Gent, Belgium, 3 Departamento de EcologõÂa Funcional y a1111111111 Evolutiva, EstacioÂn Experimental de Zonas A ridas (CSIC), AlmerõÂa, Spain a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract Host defences against cuckoo parasitism and cuckoo trickeries to overcome them are a classic example of antagonistic coevolution. Recently it has been reported that this relation- OPEN ACCESS ship may turn to be mutualistic in the case of the carrion crow (Corvus corone) and its brood Citation: Soler M, de Neve L, RoldaÂn M, PeÂrez- parasite, the great spotted cuckoo (Clamator glandarius), given that experimentally and nat- Contreras T, Soler JJ (2017) Great spotted cuckoo urally parasitized nests were depredated at a lower rate than non-parasitized nests. This nestlings have no antipredatory effect on magpie or carrion crow host nests in southern Spain. PLoS result was interpreted as a consequence of the antipredatory properties of a fetid cloacal ONE 12(4): e0173080. https://doi.org/10.1371/ secretion produced by cuckoo nestlings, which presumably deters predators from parasit- journal.pone.0173080 ized host nests. This potential defensive mechanism would therefore explain the detected Editor: Elsa Addessi, Consiglio Nazionale delle higher fledgling success of parasitized nests during breeding seasons with high predation Ricerche, ITALY risk. Here, in a different study population, we explored the expected benefits in terms of Received: April 13, 2015 reduced nest predation in naturally and experimentally parasitized nests of two different Accepted: February 12, 2017 host species, carrion crows and magpies (Pica pica). -

NOTES. CARRION CROW DISPLAYING to HOODED CROW. on March 13Th, 1949,1 Was Watching a Single Hooded Crow (Corvus Comix) on the Heath Near Icklingham, Suffolk

(242) NOTES. CARRION CROW DISPLAYING TO HOODED CROW. ON March 13th, 1949,1 was watching a single Hooded Crow (Corvus comix) on the heath near Icklingham, Suffolk. A Carrion Crow [Corvus corone) settled near by and hopped up close to the Hoodie which however took no notice but continued feeding on some objects on the ground. The Carrion Crow then retreated a few yards and jumped up in the air alighting close to where it left the ground. This was repeated several times but evoked no response from the feeding bird and the Carrion Crow flew away. On reference to The Handbook I was surprised to find this type of display attributed to the Hooded Crow only. C. F. TEBBUTT. [Although the type of display referred to does not appear to have been recorded in the Carrion Crow it cannot be doubted that the displays of the two birds are really identical. As is well known they interbreed freely where the ranges of the two forms meet, as in Scotland, and it has been held with much justice that they should be regarded as forms of one species [cf. antea, pp. 165-166)—EDS.] COITION OF CARRION CROW ON GROUND. WITH reference to the Carrion Crow [Corvus corone) The Handbook of British Birds (Vol. 1, p. 15) states : " Coition observed both on nest and in neighbouring tree." In the circumstances it may be of interest to record that on the afternoon of March 13th, 1949, in a pasture at Low Gosforth, Northumberland, I observed a pair of Carrion Crows in the act of copulating on the ground, the cock being mounted on the hen with wings flapping. -

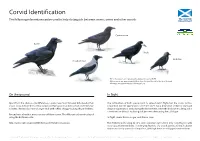

Corvid Identification Leaflet

Corvid Identification The following information can be used to help distinguish between ravens, crows and other corvids Carrion crow Raven Rook Jackdaw Hooded crow These illustrations are reproduced by kind permission of RSPB. Mature ravens are approximately 64cm from the tip of the tail to the tip of the beak. All images are approximately 1/8 th actual size. On the ground In flight Apart from the obvious size differences, ravens have much broader bills (beaks) than The tail feathers of both species tend to spread out in flight, but the crow’s tail has crows. Crow bills are finer, with a longer, sweeping curve to the top half of the bill than a rounded, fan-like appearance, while the raven has a distinctive wedge or diamond a ravens. Ravens also have a longer neck with ruffled, shaggy-looking throat feathers. shape in appearance. Only during the late summer, when the birds are moulting, will it sometimes be difficult to distinguish between them using the tail shape. Ravens have a harsher, more rasping call than a crow. The different calls can be played using the RSPB web-site: In flight, ravens have a longer neck than a crow. http://www.rspb.org.uk/wildlife/birdguide/families/crows.asp. The feathers at the wing-tip of a raven separate out to form very long ‘fingers’, with much space between them. The wing-tip feathers of a crow however, are much shorter and more closely spaced in comparison, although there are still gaps between them. This identification sheet was prepared by the Photography Unit, Science and Advice for Scottish Agriculture (SASA), Roddinglaw Road, Edinburgh, EH12 9FJ, UK. -

Winter Japan: Cranes & Sea Eagles 2019

Field Guides Tour Report Winter Japan: Cranes & Sea Eagles 2019 Jan 25, 2019 to Feb 9, 2019 Phil Gregory & Jun Matsui For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Steller's Sea-Eagle is classified as Vulnerable, although this individual, striding along like an enraged samurai, looks anything but!! This magnificent bird is always a highlight of the tour, and we were very pleased to see about 150 of them at Rausu. Photo by participant Becky Hansen. This was my fifteenth winter Japan trip, though beset by some weather issues with heavy snow at the snow monkeys, then rain on Kyushu and high winds on Hokkaido which cost us a day there when we were unable to land. Finally, we had some worries about snow at Haneda on departure day, which thankfully did not impact us much; let's hope for more settled conditions in 2020. We began as usual at Narita, where a Brown-headed Thrush was at Tokko creek not far from the hotel; it was the only one we saw. The striking Japanese Wagtail made its first appearance, but there was no sign of the Falcated Duck and Meadow and Black-faced Buntings I’d seen the previous day, though a flyover Goshawk was a good find. Karuizawa was not very snowy, so there were no ice hazards this time. Our initial afternoon trip to Saku gave us our first Smew, plus fantastic close Baikal Teal and a single drake Falcated Duck as we were leaving, plus easy Long-billed Plover, though duck numbers were low due to the icy conditions there. -

Notes. Unusual Call of Carrion Crow

(322) NOTES. UNUSUAL CALL OF CARRION CROW. IN reference to Mr. Mayo's note (trntea, vol. xliii, p. 368), the call he mentions, which he aptly likens to the sound of a distant machine- gun or the drumming of a woodpecker, is regularly used by Carrion Crows (Corvus corone) in parts of Surrey and Middlesex and doubt• less elsewhere as well. In the versions I have heard, this note has the same mechanical quality as the clicking notes of the female Jay (Garrulus glandarius) and it is uttered in the same posture as the Jay uses (vide, ante a, vol. xlii, pp. 278-285). This note is heard usually at excited gatherings involving not fewer than two pairs of Carrion Crows. Whether this note is used only by the female I cannot say, but I strongly suspect so, as on occasions when four Crows have been involved I have never seen more than two of them utter this note. Sometimes this note is uttered in flight and in this case the same posturing is used as when perched, which suggests that this arching of the back, and forward and downward reaching of the head is to be considered primarily as necessary for producing the note and only secondarily as a display. This note, or one essentially similar, I have heard from a Rook {Corvus frugilegus) in Yorkshire and also from Hooded Crows (C. comix) in Egypt, but foolishly I did not write down any details at the time. Some years before the war a captive Hooded Crow in Chessington Zoo, responded to my talking to it by giving these notes with appropriate posturings just as a tame female Jay will often do. -

Crows and Ravens As Indicators of Socioeconomic and Cultural Changes in Urban Areas

sustainability Article Crows and Ravens as Indicators of Socioeconomic and Cultural Changes in Urban Areas Karol Król * and Józef Hernik Digital Cultural Heritage Laboratory, Department of Land Management and Landscape Architecture, Faculty of Environmental Engineering and Land Surveying, University of Agriculture in Kraków, Balicka 253c, 30-149 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-12-662-40-16 Received: 5 November 2020; Accepted: 7 December 2020; Published: 8 December 2020 Abstract: Crows and ravens are deeply symbolic. They have featured in myriads of myths and legends. They have been perceived as ominous, totemic, but also smart and intelligent birds by various peoples around the world. They have heralded bad luck and evoked negative associations. How are they perceived today, in the time of the Internet, mobile devices, and popular culture? Is the young generation familiar with the legends, tales, or beliefs related to these birds? The purpose of this paper was to determine the place of the crow and raven in the consciousness of young generations, referred to as Generation Y and Generation Z. The authors proposed that young people, Generations Y and Z, were not familiar with the symbolism of crows and ravens, attached no weight to them, and failed to appreciate their past cultural roles. The survey involved respondents aged 60 and over as well. Both online surveys and direct, in-depth, structured interviews were employed. It was demonstrated that the crow and raven are ominous birds that herald bad luck and evoke negative associations and feelings in the consciousness of young generations.