NVS 3-1-4 J-Jones

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customer Order Form

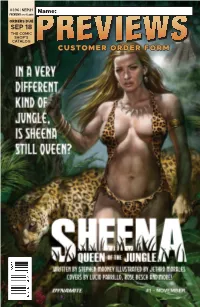

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Martial Arts

Stock #37-2614 COVER ART INTERIOR ART CONTENTS Bob Stevlic Greg Hyland JupiterImages FROM THE EDITOR . 3 HARDCORE . 4 by Stephen Dedman N HIS THE THREE BROTHERS I T SCHOOLS OF MARTIAL ARTS . 13 by Alan Leddon ISSUE FIGHT WHILE IN FLIGHT . 17 by Kelly Pedersen The righteous battle never ends – certainly not with this, the Martial Arts issue of Pyramid. With two new adventures, eight INSTANT TOURNAMENT. 21 new styles for GURPS Martial Arts, and other dojo-powered delights, this issue is sure to have something to add punch to THE GROOM OF your two-fisted campaigns. THE SPIDER PRINCESS . 24 Heroes need to get Hardcore in a modern-day adventure by J. Edward Tremlett centered on illegal (and immoral) underground fighting. Do the PCs have the guts and skill to break up this operation? RANDOM THOUGHT TABLE: NO BLOOD, What started as a school of martial arts run by three broth- NO GUTS, NO PROBLEM!. 35 ers has splintered into three different schools – each with its by Steven Marsh, Pyramid Editor own focus. Sadly, although the schools teach effective skills, they do not teach particularly honorable ones . Learn the ODDS AND ENDS . 37 secrets of this family business, plus three GURPS Martial Arts styles, in The Three Brothers School of Martial Arts. APPENDIX Z: Many martial-arts students have been criticized for having THE CRUMBLING GROUND . 38 their heads in the clouds, but Fight While in Flight shows the other side of this admonition. These five GURPS Martial Arts ABOUT GURPS . 40 styles are designed for fighters looking to make best use of their ability to fly, jump, or aerially maneuver. -

Morlock Night Free

FREE MORLOCK NIGHT PDF K. W. Jeter | 332 pages | 26 Apr 2011 | Watkins Media | 9780857661005 | English | London, United Kingdom Morlock Night by K. W. Jeter: | : Books Having acquired a device for themselves, the brutish Morlocks return from the desolate far future to Victorian England to cause mayhem and disruption. But the mythical heroes of Old England have also returned, in the hour of the country's greatest need, to stand between England and her total destruction. Search books and Morlock Night. View all online retailers Find local retailers. Also by KW Jeter. Praise for Morlock Night. Related titles. A Deadly Education. Roald Morlock NightQuentin Blake. The Night Circus. Philip PullmanChristopher Wormell. D A Tale of Two Morlock Night. Good Omens. Neil GaimanTerry Pratchett. His Dark Materials. Trial of the Wizard King. Star Wars: Victory's Price. Violet Black. Beneath the Keep. The Absolute Book. The Morlock Night Devil. The Stranger Times. The Ruthless Lady's Guide to Wizardry. The Orville Season 2. The Bitterwine Oath. Our top books, exclusive content and competitions. Straight to your inbox. Sign Morlock Night to our newsletter using your email. Enter your email to sign up. Thank you! Your subscription to Read More was successful. To help us recommend your next book, tell us what you enjoy reading. Add your interests. Morlock Night - Wikipedia Morlock Night acquired a Morlock Night for themselves, the brutish Morlocks return from the desolate far future to Victorian England to cause mayhem and disruption. When you buy a book, we donate a book. Sign in. Halloween Books for Kids. Morlock Night By K. -

ALEX ROSS' Unrealized

Fantastic Four TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.118 February 2020 $9.95 1 82658 00387 6 ALEX ROSS’ DC: TheLost1970s•FRANK THORNE’sRedSonjaprelims•LARRYHAMA’sFury Force• MIKE GRELL’sBatman/Jon Sable•CLAREMONT&SIM’sX-Men/CerebusCURT SWAN’s Mad Hatter• AUGUSTYN&PAROBECK’s Target•theill-fatedImpact rebootbyPAUL lost pagesfor EDHANNIGAN’sSkulland Bones•ENGLEHART&VON EEDEN’sBatman/ GREATEST STORIESNEVERTOLDISSUE! KUPPERBERG •with unpublished artbyCALNAN, COCKRUM, HA,NETZER &more! Fantastic Four Four Fantastic unrealized reboot! ™ Volume 1, Number 118 February 2020 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Alex Ross COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Brian Augustyn Alex Ross Mike W. Barr Jim Shooter Dewey Cassell Dave Sim Ed Catto Jim Simon GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Alex Ross and the Fantastic Four That Wasn’t . 2 Chris Claremont Anthony Snyder An exclusive interview with the comics visionary about his pop art Kirby homage Comic Book Artist Bryan Stroud Steve Englehart Roy Thomas ART GALLERY: Marvel Goes Day-Glo. 12 Tim Finn Frank Thorne Inspired by our cover feature, a collection of posters from the House of Psychedelic Ideas Paul Fricke J. C. Vaughn Mike Gold Trevor Von Eeden GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: The “Lost” DC Stories of the 1970s . 15 Grand Comics John Wells From All-Out War to Zany, DC’s line was in a state of flux throughout the decade Database Mike Grell ROUGH STUFF: Unseen Sonja . 31 Larry Hama The Red Sonja prelims of Frank Thorne Ed Hannigan Jack C. Harris GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Cancelled Crossover Cavalcade . -

Convergence Culture Reconsidered

Reconsidering Transmedia(l) Worlds Nicole Gabriel, Bogna Kazur, and Kai Matuszkiewicz 1. Introduction “Any thoughtful study of contemporary transmedia must start with the vital caveat that transmedia is not a new phenomenon, born of the digital age.” (Jason Mittell 2014, 253; emphasis in the original) To begin with, we would like to agree with the general sentiment of Mittell’s statement: ‘transmedia,’ which Mittell seems to use as an abbreviation of the term ‘transmediality,’ is not a new phenomenon. But can it really be a mere coincidence that these two terms and other related concepts such as ‘transmedial worlds’ have been introduced and extensively discussed in academic discourses since the early 2000s, less than ten years after the introduction of home computers and the inter- net to numerous private households, and at about the same time as the Web 2.0 came into existence? We do not think so. Rather, we believe that the increasing research interest of media studies in these phenomena and the various concepts used in this research field are indicators of a fundamental change in (trans)media culture that is a result of the emergence of digital technologies as well as their mas- sive influence on our everyday lives. The aims of this paper are to take a closer look at the terminology used to de- scribe different phenomena in the field of transmedia studies, to differentiate be- tween these terms and concepts and render them more precise, and to put trans- media(l) worlds into a historical context through the analysis of three case studies: the transmedial universe of Sherlock Holmes, the Alien saga, and the transmedial world of The Legend of Zelda. -

Lovecraft Research Paper Final Draft

Nagelvoort 1 Chris Nagelvoort Professor Walsh Humanities Core H1CS 13 June 2020 Becoming Anti-Human: How Lovecraftian Horror Philosophically Deconstructs Otherness The most horrifying monster is change. Having the comfort and consistency of normality be thrust into the foreign landscape of difference can be petrifying. The dormant mind can lose its sense of self, security, and, worst of all, control. In the horror genre, this is no different. Monsters are frightening because of the difference they impose on us and our identity. Imagining a world ruled by a zombie apocalypse or a ravenous vampire feasting at night may seem unobtrusive, but when the rabid ghoul trespasses the border of detached fiction into the interior of one’s identity, the cliche skeleton seems almost an afterthought. Much more terrifying than the grotesqueness or typicality of these horror villains is how they can turn one’s sense of self and control inside out. It invites the elusive glance inward, asking the subject to wonder if their pillars of psychological safety—identity, family, belief system, home—are very safe at all. This fear of something different is compartmentalized by the psyche as something so alien, so invasive, that it must be something Other. This effect is explored by the stories of Howard Philips Lovecraft, a horror writer whose stories are so bizarre that the average reader is stripped of all their preconceptions about reality and even their sense of self. This special subgenre of horror was pioneered by Lovecraft and is famously called “Lovecraftian horror” but is well known today as cosmic horror: A mesh of horror and science fiction that “erodes presumptions about the nature of reality” (Cardin 273). -

Rose Gardner Mysteries

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. Est. 1994 RIGHTS CATALOG 2019 JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. 49 W. 45th St., 12th Floor, New York, NY 10036-4603 Phone: +1-917-388-3010 Fax: +1-917-388-2998 Joshua Bilmes, President [email protected] Adriana Funke Karen Bourne International Rights Director Foreign Rights Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @awfulagent @jabberworld For the latest news, reviews, and updated rights information, visit us at: www.awfulagent.com The information in this catalog is accurate as of [DATE]. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. Table of Contents Table of Contents Author/Section Genre Page # Author/Section Genre Page # Tim Akers ....................... Fantasy..........................................................................22 Ellery Queen ................... Mystery.........................................................................64 Robert Asprin ................. Fantasy..........................................................................68 Brandon Sanderson ........ New York Times Bestseller.......................................51-60 Marie Brennan ............... Fantasy..........................................................................8-9 Jon Sprunk ..................... Fantasy..........................................................................36 Peter V. Brett .................. Fantasy.....................................................................16-17 Michael J. Sullivan ......... Fantasy.....................................................................26-27 -

Read Book Sherlock Holmes Vs Dracula

SHERLOCK HOLMES VS DRACULA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Loren D. Estleman | 208 pages | 09 Nov 2012 | Titan Books Ltd | 9781781161425 | English | London, United Kingdom Sherlock Holmes vs Dracula PDF Book Your use of the site and services is subject to these policies and terms. Was the bought-for-mega bucks Medieval anywhere near faultless? Gallery Books. I sincerely hope that DC Comics moves forward with this series. The supremely rational Holmes also proves remarkably quick to accept the reality of vampire s on the basis of very little evidence. Adapted for radio by Glyn Dearman from Loren D. Rather than crafting a whole new narrative that would cast aside everything in the original Dracula and face criticism for changing a lot of things, this book works as a companion piece, an add-on to the classic. With Simon Davis he recently worked on a survival horror series, Stone Island, and he has also produced a comic version of the computer game Hellgate: London with Steve Pugh. I am also able to admit when I'm wrong. Victorian Undead 2 books. Edited by ImportBot. Add to the confounded confusion - Van Helsing, Dracula and the lot! Professor Stark once again will take the Wayback Machine down to the lowermost levels of development hell, armed only with a crucifix, a feather duster and his trusted fireplace bellows to brush off an old spec script that deservedly— and with due market diligence — should rise again. Hyde and the Invisible Man in one fell swoop. My Top How do you write a period piece that will both appeal to purists, fanboys, tweens and civilians alike? Log in or register to write something here or to contact authors. -

The Graphic Novel, a Special Type of Comics

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02523-3 - The Graphic Novel: An Introduction Jan Baetens and Hugo Frey Excerpt More information Introduction: The Graphic Novel, 1 a Special Type of Comics Is there really something like the graphic novel? For good or ill, there are famous quotations that are frequently repeated when discussing the graphic novel. They are valued because they come from two of the key protagonists whose works from the mid-1980s were so infl uential in the concept gaining in popularity: Art Spiegelman, the creator of Maus , and Alan Moore, the scriptwriter of Watchmen . Both are negative about the neologism that was being employed to describe the longer-length and adult-themed comics with which they were increas- ingly associated, although their roots were with underground comix in the United States and United Kingdom, respectively. Spiegelman’s remarks were fi rst published in Print magazine in 1988, and it was here that he suggested that “graphic novel” was an unhelpful term: The latest wrinkle in the comic book’s evolution has been the so-called “graphic novel.” In 1986, Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns , a full-length trade paperback detailing the adventures of the superhero as a violent, aging vigilante, and my own MAUS, A Survivor’s Tale both met with com- mercial success in bookstores. They were dubbed graphic novels in a bid for social acceptability (Personally, I always thought Nathaniel West’s The 1 © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02523-3 - The Graphic Novel: An Introduction Jan Baetens and Hugo Frey Excerpt More information 2 The Graphic Novel: An Introduction Day of the Locust was an extraordinarily graphic novel, and that what I did was . -

May 2017 New Releases

MAY 2017 NEW RELEASES GRAPHIC NOVELS • MANGA • SCI-FI/ FANTASY • GAMES VORACIOUS : FEEDING TIME Hunting dinosaurs and secretly serving them at his restaurant, Fork & Fossil, has helped Chef ISBN-13: 978-1-63229-235-3 Nate Willner become a big success. But just when he’s starting to make something of his life, Price: $17.99 ($23.99 CAN) Publisher: Action Lab he discovers that his hunting trips with Captain Jim are actually taking place in an alternate Entertainment reality – an Earth where dinosaurs evolve into Saurians, a technologically advanced race that Writer: Markisan Naso rules the far future! Some of these Saurians have mysteriously started vanishing from Artist: Jason Muhr Cretaceous City and the local authorities are hell-bent on finding who’s responsible. Nate’s Page Count: 160 world is about to collide with something much, much bigger than any dinosaur he’s ever Format: Softcover, Full Color Recommended Age: Mature roasted. Readers (ages 16 and up) Genre: Science Fiction Collecting VORACIOUS: Feeding Time #1-5, this second volume of the critically acclaimed Ship Date: 6/6/2017 series serves up a colorful bowl of characters and a platter full of sci-fi adventure, mystery and heart! SELECTED PREVIOUS VOLUMES: • Voracious: Diners, Dinosaurs & Dives (ISBN-13 978-1-63229-165-3, $14.99) PROVIDENCE ACT 1 FINAL PRINTING HC Due to overwhelming demand, we offer one final printing of the Providence Act 1 Hardcover! ISBN-13: 978-1-59291-291-9 Alan Moore’s quintessential horror series has set the standard for a terrifying reinvention of Price: $19.99 ($26.50 CAN) Publisher: Avatar Press the works of H.P. -

Customer Order Form

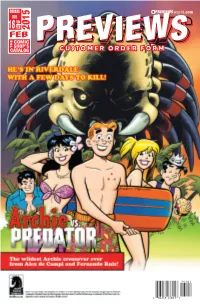

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 FEB 2015 FEB COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/8/2015 3:45:07 PM Feb15 IFC Future Dudes Ad.indd 1 1/8/2015 9:57:57 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS The Shield #1 l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS 1 Sonic/Mega Man: Worlds Collide: The Complete Epic TP l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Crossed: Badlands #75 l AVATAR PRESS INC Extinction Parade Volume 2: War TP l AVATAR PRESS INC Lady Mechanika: The Tablet of Destinies #1 l BENITEZ PRODUCTIONS UFOlogy #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS Lumberjanes Volume 1 TP l BOOM! STUDIOS 1 Masks 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Jungle Girl Season 3 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Uncanny Season 2 #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Supermutant Magic Academy GN l DRAWN & QUARTERLY Rick & Morty #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Bloodshot Reborn #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC GYO 2-in-1 Deluxe Edition HC l VIZ MEDIA LLC BOOKS Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books l COMICS Taschen’s The Bronze Age Of DC Comics 1970-1984 HC l COMICS Neil Gaiman: Chu’s Day at the Beach HC l NEIL GAIMAN Darth Vader & Friends HC l STAR WARS MAGAZINES Star Trek: The Official Starships Collection Special #5: Klingon Bird-of-Prey l EAGLEMOSS Ace Magazine #2 l COMICS Ultimate Spider-Man Magazine #3 l COMICS Doctor Who Special #40 l DOCTOR WHO 2 TRADING CARDS Topps 2015 Baseball Series 2 Trading Cards l TOPPS COMPANY APPAREL DC Heroes: Aquaman Navy T-Shirt l PREVIEWS EXCLUSIVE WEAR 2 DC Heroes: Harley Quinn “Cells” -

Microsoft Visual Basic

$ LIST: FAX/MODEM/E-MAIL: aug 23 2021 PREVIEWS DISK: aug 25 2021 [email protected] for News, Specials and Reorders Visit WWW.PEPCOMICS.NL PEP COMICS DUE DATE: DCD WETH. DEN OUDESTRAAT 10 FAX: 23 augustus 5706 ST HELMOND ONLINE: 23 augustus TEL +31 (0)492-472760 SHIPPING: ($) FAX +31 (0)492-472761 oktober/november #557 ********************************** __ 0079 Walking Dead Compendium TPB Vol.04 59.99 A *** DIAMOND COMIC DISTR. ******* __ 0080 [M] Walking Dead Heres Negan H/C 19.99 A ********************************** __ 0081 [M] Walking Dead Alien H/C 19.99 A __ 0082 Ess.Guide To Comic Bk Letterin S/C 16.99 A DCD SALES TOOLS page 026 __ 0083 Howtoons Tools/Mass Constructi TPB 17.99 A __ 0019 Previews October 2021 #397 5.00 D __ 0084 Howtoons Reignition TPB Vol.01 9.99 A __ 0020 Previews October 2021 Custome #397 0.25 D __ 0085 [M] Fine Print TPB Vol.01 16.99 A __ 0021 Previews Oct 2021 Custo EXTRA #397 0.50 D __ 0086 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.01 14.99 A __ 0023 Previews Oct 2021 Retai EXTRA #397 2.08 D __ 0087 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.02 14.99 A __ 0024 Game Trade Magazine #260 0.00 N __ 0088 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.03 14.99 A __ 0025 Game Trade Magazine EXTRA #260 0.58 N __ 0089 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.04 14.99 A __ 0026 Marvel Previews O EXTRA Vol.05 #16 0.00 D __ 0090 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.05 14.99 A IMAGE COMICS page 040 __ 0091 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.06 16.99 A __ 0028 [M] Friday Bk 01 First Day/Chr TPB 14.99 A __ 0092 [M] Sunstone Ogn Vol.07 16.99 A __ 0029 [M] Private Eye H/C DLX 49.99 A __ 0093 [M] Sunstone Book 01 H/C 39.99 A __ 0030 [M] Reckless