Umi-Ku-2441 1.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Table of Contents An Introduction to Pondicherry Park Curriculum The Mission of Lakes Environmental Association’s Education Program A Teacher’s Guide for taking Students into Pondicherry Park How to use the Pondicherry Park Lessons Social Studies: Grades K-2 Let’s Make a Map Pondicherry Clean up Grades 3-5 Guided Imagery through the History of Pondicherry Park I Guided Imagery through the History of Pondicherry Park II Pondicherry Park Clean Up Town Meeting English Language Arts Grades K-2 Pondicherry Story Word Scavenger Hunt Grades 3-5 Dear Pondicherry Park Mathematics Grades K-2 Nature’s Geometry The Counting Classroom Grades 3-5 Forest Funds Science and Technology Grades K-2 Man-Made or Natural Walk Nature’s Puzzle Pieces Grades 3-5 Collecting the Annual Weather I Collecting the Annual Weather II Collecting the Annual Weather III Pondicherry Ecosystems I Pondicherry Ecosystems II Pondicherry Park Research Questions The Web of Life Resources Our Mission Our mission for the Lakes Environmental Association’s education program is to encourage an understanding of and connection to place, with the belief that a connection to the local environment is the foundation for lasting environmental stewardship. LEA’s place-based approach to environmental education incorporates important science skills to help students understand the environment. LEA’s continuous educational programming in MSAD 61 builds and reinforces understanding of scientific concepts over students’ educational careers. With the use of the Pondicherry Park Curriculum, and the help of their teachers, the region’s students will build stronger connections to their local environment while learning the important information required by the Maine Learning Results. -

Fall 2011 Welcome Back BBQ Winners

Toy Shop By: Erin Frevert This place has a long history. I’ve lived here my whole life, but my ancestors have been here for practically forever. We’ve never fit in anywhere because of how different our appearance is from the “norm.” Our short stature and pointed ears made us easy targets for snide remarks and unbearable glances. Eventually we reached our breaking point; my ancestors decided it would be best to remove themselves from the society that was so cruel and move north, as far north as possible, to the North Pole. Once at the North Pole, my ancestors built a settlement and began making a living by building toys. They wanted to become the number one toy corporation in the world to show the people that looked down on them as children that they are not children and are capable for running such a successful corporation. My ancestors tried their hardest to make their toy factory number one in the world; however, they were never successful. They would work their fingers to the bone 364 days a year to meet their quota, but on the day the evaluator would come, everything would be gone. This would happen year after year, and the elves were getting frustrated, so they decided to put up a security camera and have some of the top elves guard the doors to the factory. All night, there were no disturbances, yet when the evaluator came, all of the toys were gone! The elves couldn’t figure out how all the toys had disappeared until they reviewed their security tapes. -

The Aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement and the Negation of the Old American Dream

Pedagogy of the Block: The Aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement and the Negation of the old American Dream By Hodari Arisi Touré A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Daniel Perlstein, Chair Professor Na‘ilah Suad Nasir Professor Carolyn Finney Spring, 2011 Pedagogy of the Block: The Aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement and the Negation of the old American Dream © 2011 by Hodari Arisi Touré Abstract Pedagogy of the Block: The Aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement and the Negation of the Old American Dream by Hodari Arisi Toure' Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Daniel Perlstein, Chair The constraining role of racial, social, and economic stratification on the lives and education of African American males has been argued both theoretically and empirically (Massey, 2007; MacLeod, 1987; Noguera, 2001). Some have argued that one important mechanism is the perception of limited opportunity structures (Noguera, 2004; Ogbu, 1987). This dissertation explored how real and perceived opportunity structures were shaped by political, social, and economic forces in an urban neighborhood. Specifically, this study focused on a core group of Black males in a bounded historical time and geographic locale and explored how life pathways were identified, conveyed, and chosen. This study was historically situated in the period starting with the inception of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1966, until the time of the death of its co-founder, Huey P. -

SPIDER-MAN by David Koepp

"SPIDER-MAN" by David Koepp Based on Characters Created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko FADE IN: EXT. A BACK ALLEY - DAY The screen is filled by the face of PETER PARKER, a seventeen year old boy. High school must not be any fun for Peter, he's one hundred percent nerd- skinny, zitty, glasses. His face is just frozen there, a cringing expression on it, which strikes us odd until we realize the image is freeze framed. PETER (V.O.) Look, I'm going to warn you right up front. If somebody told you this was a happy story, if somebody said I was just your average, ordinary seventeen year old, not a care in the world... The image un-freezes. A FIST, at the end of a right hook, comes into frame and punches poor Peter. His head snaps back and bounces forward, his eyes roll. PETER (V.O.) (cont'd) ...somebody lied. The image freezes again, Peter's glasses dangling from one ear. PETER (V.O.) (cont'd) That's me. Peter Parker. A.K.A. Spider-Man, but not yet. Gotta go through some ritual humiliation first. All right, I didn't want you to see me like this, but we might as well get it over with. The image unfreezes again, another fist comes into frame, this one a left cross. It CRUNCHES into Peter's nose and he crumples to the pavement in this alley in the city. THREE HIGH SCHOOL PUNKS commence pounding the crap out of him. FLASH THOMPSON is the leader, he's seventeen, good-looking, body of a twenty-eight year old. -

AMERICAN SKIN: a New Musical Music by Joshua Davis Book and Lyrics by Eric C

AMERICAN SKIN: A New Musical Music by Joshua Davis Book and Lyrics by Eric C. Jones Based on True Events Revised Version @ 2016 2615 Leadpoint Dr. Original Version @ 2006 Missouri City, Texas 77459 [email protected] 8326877738 1. ACT_____ I Place: Coney Island, New York City, New York. A dream-like setting which loosely resembles an old, dilapidated section of a Coney Island Boardwalk. A world filled with amusements, "carnie" booths, concession stands, nightclubs, and sideshows. Time: Early 21st Century. Present time. Early Evening. Scene_______ I The play opens up with another start of another business night. (Play Rock overture) Enter GUITAR HERO as HE starts to play scales and begins to riff while two people are passing by. THEY don't drop any money into HIS pot. HE continues to play. The local carnies and the local sideshow performers are setting up their stands. Enter BIG LOUIE as HE is opens up HIS Club Inferno. HE kisses HIS girls; DESTINY, ECSTASY and FANTASY on their cheeks as THEY arrive to start another night shift. As the sets are complete and in place, the entire cast are scattered throughout various sections of the stage.THEY freeze except the GUITAR HERO as he continues to play. Enter MIKEY MIKE , the Emcee of the Great American Sideshow as HE faces the audience. Track One- " BUSINESS AS USUAL " (Alternative Rock) MIKEY MIKE (Sings) YOU WON'T FIND A PLOT LIKE THIS ON REALITY TV; HOTTEST TICKET IN TOWN, A TRUE SIGHT TO SEE. CHARACTERS SO AMAZING, IT'S HARD TO BELIEVE; WHAT A MAD AUTHOR'S VISION WOULD CONCEIVE. -

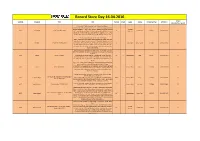

Record Store Day 16.04.2016 AT+CH Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN (Ja/Nein/Über Wen?)

Record Store Day 16.04.2016 AT+CH Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN (ja/nein/über wen?) Picture disc LP with artwork by Drew Millward (Foo Fighters) Broken Thrills is Beach Slang's first European release, compiling their debut EPs, both released in the US in 2014. The LP is released via Big Scary Monsters Big Scary ALIVE Beach Slang Broken Thrills (RSD 2016) LP 1 Independent 6678317 5060366783172 AT (La Dispute, Gnarwolves, Minus The Bear) and coincides with their first tour Monsters outside of the States, including Groezrock festival in Belgium and a run of UK headline dates. For fans of: Jawbreaker, Gaslight Anthem and Cheap Girls. 12'' Clear Vinyl, 4 Remixes of "Get Lost" + One Cover After the new album "Still Waters" recently released, and sustained by the lively "Back For More" and the captivating "2Good4Me", Breakbot is back ALIVE Breakbot Get Lost Remixes (RSD 2016) with a limited edition EP of 4 "Get Lost" remixes and one exclusive cover by 12" 1 Ed Banger Disco / Dance 2156290 5060421562902 AT the band Jamaica. Still with his sidekick Irfane, Breakbot is more than ever determined to make us dance with a new succession of hits each one more exciting than the last. LIMITED DOUBLE 12'' WITH PRINTED INNER SLEEVES: "ACTION" IS THE 1ST SINGLE OF CASSIUS 'S NEW ALBUM (release date 24.06.2016). This EP features 6 TRACKS, ALIVE Cassius Action (RSD 2016) Exclusively for the Record Store Day, the first single "Action" from the 12" 2 Because Music House 2156427 5060421564272 AT upcoming album releases as a double 12'' edition. -

The Most Trusted Name in Radio Issue 2154 May 9 1997

THE MOST TRUSTED NAME IN RADIO ISSUE 2154 MAY 9 1997 www.americanradiohistory.com . get ready to do some "LOVE II LOVE" on your desk now. ADD DATE: MAY FROM THE CRITIQUE LP "FOREVE Coreé G ENTER RINMENT www.americanradiohistory.com First Person Inside As TOLD To BEN FONG-TORRES 4 News 9 That's Sho-Biz 10 Friends of Radio Bill Paxton Glen Ballard 40 The Land of Ozz Rocks Editor Rob Fiend goes to On His Latest Production: Java Records the City of Ozz and takes a look around. Sharon Osborne talks Glen Bullard, one of the hottest hit- able, I hope they will look to us as a about Ozz Records, while Tony makers t f the '90s, has launched creative place to be. lommi discusses the upcoming Java Records, a joint venture with I chose to work with Capitol Sabbath reunion. Plus, a look at Capitol Records. He's also formed because of two key people here: all the,gmups slatedfor the tour. Intrepid Entertainment, aimed at Gary Gersh-his sensibility toward 48 Classifieds producing music -driven films, with artists is well known. And Charles FORMATS producer David Foster and cellular Koppeluran, chairman of EMI North ft 11 Top 40 .11/About the phone exec John McCaw. America, is an old friend and a great Music Though best-known for co-writing music man. Top 40 Profile: No Mercy and producing Alanis Morissette's If there's a common thread 13 Go Chart Jagged Little Pill, Ballard, a 43 -year- through all my work, it's that I 14 Alternative old native of Natchez, Miss., has been believe in artists.