Scope of Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BWY North West

Autumn 2019 BWY North West Events and news from across the region www.bwy.org.uk Front cover: Regional Officer Merseyside and North Photograph taken on the Wirral Janet Long Wales County Rep Circular Trail by North West 07809 886 485 Hajnal Littler Member Liz Horsefield. [email protected] 07702 021 031 See more member photos from [email protected] page 18. Regional Treasurer And if you’d like to submit a photo Sarah Peter Lancashire County Rep for our front cover, contact: 07962 038269 Brigid Middlehurst [email protected] [email protected] 07901 767343 [email protected] Regional Training Officer & Deputy Regional Committee Member Officer Sue Hargreaves Christine Royle 01925 819904 803 Altrincham Road [email protected] Brooklands Manchester M23 9AH 0161 945 2077 Please note that for 2019 [email protected] we have some new committee members with Regional Secretary updated contact details, Lorraine Coxon please do take a moment 07513 156168 to review and update your [email protected] records where required Editor Hollie Costigan 07976 294 781 [email protected] Web Administrator Russell Smithers The British Wheel of Yoga is the 07712 610 120 Sports England recognised [email protected] National Governing body for Yoga. Cheshire County Rep Safeguarding and Jackie Hudson Disclaimer Please note that the Diversity and Child 07702 711 021 views expressed in this Protection Officer [email protected] newsletter are not necessarily Rebecca Morris the views of the editor nor the [email protected] Greater Manchester & British Wheel of Yoga. 01529 306851 Isle of Man County Rep 07738 946320 Richard Fowler Any advertisements are 07840 149651 accepted in good faith and no [email protected] responsibility can be accepted CPD enquiries for the contents. -

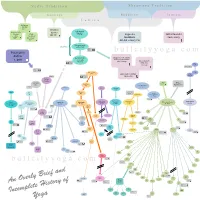

B U L L C I T Y Y O G a . C O M B U L L C I T Y Y O G a . C O M An

V e d i c t r a d i t i o n S h r a m a n a T r a d i t i o n V e d i c T r a d i t i o n S h r a m a n a t r a d i t i on S a m k h y a B u d d h i s m J a i n i s m T a n t r a Brahmanas 900-500 BCE Samkhya Bhagavad Gita Karika Adi Nanth 5th-2nd Katha (Shiva) Yogacara Tattvarthasutra century Upanishad 200 CE BCE 6th century Buddhism 2nd century BCE 4th-5th century CE Matsyendranath The Naths “Lord of Fish” Hatha Yoga Patanjali’s b u l l c i t y y o g a . c o m Sutras Gorakshanath Hatha Yoga Pradipika c. 400 11th-12th by Yogi Swatmarama Shiva Sahita Laya Century 16th Century Yoga 17th-18th Helena century Blavatsky Theosophism Raja Yoga Annie Mahavatar Babaji Besant (Saint?) Gheranda Samhita Charles Leadbeater Kriya Sikhism Circa 1700 Yoga Guru Nanak Dev Ji 15th Century John Woodroffe Yoga British (Arthur Avalon) Korunta Late 19th Lahiri Maha- Century saya Sri Madhavadasji Gymnastics v The Serpent Maharaj Power Vishwananda Bhagavan Nitkananda Krishnanand Saraswati Saraswati Dadaji Yukteswar World’ s Vishnu Parliament on Bbaskar Giri Religion Swami Lele Vivekananda Kuvalayanandav b. 1883 Asanas Brahmananda Krishnamurti Yogananda Muktananda Saraswati Ramakrishna Krishnamacharya Swami Sri Aurobindo Sivananda b. 1888 B. 1895 B. 1893 b. 1908 b. 1870 B. 1888 Kripalvananda b.1872 b. -

Yogarupa Rod Stryker Presents Parayoga Immersion Weekend at Yoga Rasa

Yogarupa Rod Stryker presents ParaYoga Immersion Weekend at Yoga Rasa AWAKENING THE TRUE POWER OF YOGA : SUN , MOON , AND FIRE with Rod Stryker March 18-20, 2011 Friday night ~ 6-8:30 Saturday morning ~ 9:30-12:30 • Saturday afternoon ~ 2-5 Sunday morning ~ 8:30-11:30 • Sunday afternoon ~ 1-3:30 Entire weekend: $249 until 2/15, $279 after Friday evening or Saturday morning only: $65 each The ancient tradition of Tantra maps the entire spectrum and sacred journey of Hatha Yoga. According to these teachings there are three stages to practice: Moon, Sun, and Fire. Knowing how and when to apply these practices, ancient wisdom tells us, is key to realizing the promise of yoga and to achieve lasting happiness and success. Join master teacher, Rod Stryker, for what promises to be an inspiring and life-changing weekend. Each class includes theory and practice. All levels welcome. Rod Stryker is the founder of ParaYoga® and widely considered one of the country's leading yoga and meditation teachers. He has taught for thirty years and leads retreats, workshops, and trainings worldwide. Rod is one of few American teachers today transmitting an ancient tradition, one that has been handed from teacher to student for literally thousands of years. Register Early ~ call Yoga Rasa or visit YogaRasa.net ! 17226 Mercury @ El Camino & Medical Center Houston, TX 77058 281-282-9400 www.yogarasa.net SESSION DESCRIPTIONS Friday PM ~ Tantra Vidya, Kundalini & the Subtle Body Through theory and practice we explore the science of Tantra, highlighting the ancient tradition’s approach to asana and beyond and its vision of where and how the worlds of mind, body and spirit meet. -

TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE and INDIA's BACKBEND on YOGA ABSTRACT One of the Biggest Global Trends of the 21St Century Is That of Pr

[VOL II] JOURNAL OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY STUDIES [ISSUE II] TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND INDIA’S BACKBEND ON YOGA RASHMI RAGHAVAN ABSTRACT One of the biggest global trends of the 21st Century is that of practising Yoga, due to its physical, mental and spiritual benefits. Developed in India almost two millennia ago, its spread to the West has increased the number of practitioners as well as made it a commercially successful business. Any business can grow only in a strong intellectual property regime. The appropriate categorization of Yoga in any IP regime is highly disputed when it becomes the subject of copyright and trademark infringement lawsuits. Yoga, by and large is traditional knowledge, as it is an informational system giving a well- defined procedure in terms of postures, breathing techniques and a holistic philosophy to raise the standard of mankind. However, the law in terms of traditional knowledge has been sui generis because the WIPO Negotiations of the Intergovernmental Committee (‘IGC’) on Traditional Knowledge ('TK’) has been unable to create an international instrument for the protection and exercise of rights of indigenous communities who claim to be collective owners of these types of TK. The situation becomes extremely precarious when knowledge like Yoga becomes widely diffused outside the community where it originated to claim monetary or moral rights over them. The author argues that Yoga as a comprehensive system fits well within the current definition of Traditional Knowledge as an Intellectual Property. However, due to its widespread nature and easy accessibility, it cannot gain as high a ground for protection as secret or sacred traditional knowledge is currently granted. -

Mastery Is the Art of 'Becoming' – a Life-Long Endeavor

Master’s Path Catalogue WARRIOR YOU SCHOLAR SAGE Mastery is the art of ‘Becoming’ – a life-long endeavor. To learn, read. To know, write. To master, teach. ~ an Indian proverb A leader in Yoga and Ayurveda training, and dedicated to serving humanity, Rasa Yoga offers various paths to support higher level training. “Rasa Yoga Master’s Path is the higher level training beyond general yoga classes that will enable you to excel in any particular life endeavor, improve your relationships, fulfill your purpose, or become a leader at work. Through training you will learn that leadership is not about a title or position, but rather leadership is directly proportionate to quality of thought and emotional mastery. My prayer for you is that you discover your greatest life possible and feel as though you are thriving and living to your fullest potential.” ~Padma Shakti, Founder of Rasa Yoga Virarupa I A first step onto वीर्रू प I Master’s Path Virarupa I Training is for the student in the beginning stages of the warrior’s path. This program offers commitment, consistency and accountability and is the foundation for a deepening life practice of Yoga. Virarupa I includes an ongoing set of workshops and assignments that can be completed within approximately 9 months to 2 years. Actual hours of study (contact hours, non-contact hours, and practicum hours) total approximately 400. This exceeds the Yoga Alliance Registry first level training standards and qualifies you for Registered Yoga Teacher (RYT) 200 status. Gain strength & stability in all aspects of life. Testimonial “What an awesome faculty, you are Yoga, you live Yoga and I could not imagine a more comprehensive program! Thank you so much for what I have learned.. -

Yoga and Tourism Is Lik Combining Mango And

Legitimacy and the selling of yoga in the “Yoga Capital of the World” – ‘Yoga and tourism is like combining mango and salt’ ME (Meia Else) van der Zee Department of Environmental Sciences Cultural Geography Chair Group Supervisor: MSc CC Lin Examiner: prof. dr. VR van der Duim MSc Leisure, Tourism and Environment Cultural Geography Chair Group Thesis Code: GEO-80436 Submission Date: 14th of August 2017 Registration Number: 930728984120 Supervisor: MSc CC Lin Examiner: prof. dr. VR van der Duim Disclaimer: This thesis is a student report produced as a part of the Master Program Leisure, Tourism and Environment. It is not an official publication and the content does not represent an official position of Wageningen University and Research Centre i “It is possible that in the not too distant future if the Indian wants to learn about India he will have to consult the West, and if the West wants to remember how they were they will have to come to us.” – Unnamed writer quoted in Gita Mehta, Karma Cola (Favero, 2003) Front Page: Picture of “Yoga at Across River Ganga Rishikesh Uttarakhand India” from the Yoga & Ayurveda Tour in Rishikesh (Memorable India Tour Operator, n.d.) ii Personal Note and Acknowledgements Before getting into the contents of this thesis report, I would like to take this opportunity to convey something directly to you, the reader, who might be about to embark on their own Master’s thesis or other research project. Uri Alon could not have been more right, when he discussed the discrepancy between the real research process and what ends up as an organized whole on paper in his enlightening TED talk. -

V Edictradition S Hramanatradition

V e d i c t r a d i t i o n S h r a m a n a t r a d i t i o n Samkhya Buddhism ―Brahmanas‖ 900-500 T a n t r a BCE Jainism ―Katha ―Bhagavad Upanishad‖ Gita‖ 6th Century 5th—2nd BCE ―Samkhya Century BCE Karika‖ Patnanjali’s Yogachara ―Tattvarthasutra‖ Buddhism 200 CE ―Sutras‖ 2nd Century CE Adi Nanth 4th –5th (Shiva?) 100 BCE-500CE Century CE The Naths Matsyendranath ―Hatha Yoga‖ Raja ―Lord of Fish‖ (Classical) Yoga Helena Guru Nanak Dev Ji Gorakshanath Blavatsky ―Sikhism‖ ―Laya Yoga‖ b. 8th century 15th Century ―Theosophists‖ “Hatha Yoga Pradipika” Annie by Yogi Swatmarama Besant 16th Centruy Charles Leadbeater ―The Serpent Power‖ Krishnanand Babu Saraswati Bhagwan Das British John Woodroffe Mahavatar Babaji Gymnastics (Arthur Avalon) (Saint?) Late 19th/early 20th century Bhagavan Ramakrishna Vivekananda ―Kriya Yoga‖ Nitkananda Vishnu Vishwananda B. 1888 b. 1863 Yoga ―Krama Vinyasa‖ Bhaskar Lele Saraswati Kurunta Dadaji Ramaswami Lahiri Mahasaya Brahmananda ―World’s ―Siddha Paliament on Yoga‖ Saraswati Bengali Mahapurush Religion‖ B. 1870 Maharaj ―Integral Yoga‖ Baba Muktananda Krishnamurti B. 1908 A.G. Krishnamacharya B. 1895 Sri Sivananda Yukteswar Giri Nirmalanda Auribindo Mirra Ghandi Mohan B. 1888 B. 1872 Alfassa B. 1887 ―Transcendental Swami ―Kundalini ―Divine Meditation‖ Chidvilasananda Kailashananda Indra Yoga‖ 1935 Life Desikachar Devi Swami Society‖ Yogananda Maharishi (son) Kripalvananda Sri Mahesh Yogi Auribindo b. 1893 ―viniyoga‖ b. 1913 Asharam Bishnu Ghosh ―Ashtanga Yogi ―Autobiography Dharma Mittra Gary Yoga‖ ―Light of a Yogi‖ (brother) Mahamandaleshwar Kraftsow BKS on Bhajan Nityandanda b. 1939 Patabhi Jois Iyengar Yoga‖ b. -

Power and Abuse

Trigger warning: these pages contain information on abuse in yoga Power and abuse Regarded author and teacher, had no firm agenda, other than to get a sense of how he sees the book positioned within the overarching issue of Matthew Remski, renowned for his abuse; and more importantly, to try and get something of a handle on the intangible issue that has been lurking at the work on highlighting physical and back of my mind. That issue is one of power; and of the emotional injury in yoga, talks to various dynamics that are in play where issues of power are brought to the table. Or in this case, to the yoga mat. Gillian Osborne I am no scholar, but I am also no stranger to an academic I pre-ordered Practice and All is Coming. Not from text book and I have spent enough time in study to some morbid fascination with the sordid details recognise considered, informed opinion and original of other people’s experiences, but from an almost thought. Conversing with Matthew was both illuminating and fearful yet compelling desire to look into the heart of inspiring. And comfortable! Much of his conversation flowed one of the significant practice traditions and to see from an apparent and deep knowledge of these issues and what else lay there, alongside yoga, intertwined with any attempts to better his eloquent phraseology would it. The stories are shocking but entirely believable, most likely fail in spectacular fashion so I have quoted him presented rationally by the author whose meticulous directly where attempts to paraphrase seemed inadequate. -

MOVING and FEELING - Yoga, Emotion, Values and Motivation Sigrid Steen Haugen

Sigrid Steen Haugen Sigrid Steen Haugen Sigrid Steen MOVING AND FEELING An exploration of the play between motion, emotion and motivation in yoga practitioners in Norway. Master's thesis in Religious Studies Master's thesis Master's Supervisor: Gabriel Levy & Sven Bretfeld Trondheim, September 2016 MOVING AND FEELING - yoga, emotion, values and motivation emotion, values AND FEELING - yoga, MOVING NTNU Faculty of Humanities Faculty Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies Department of Philosophy Norwegian University of Science and Technology of Science University Norwegian Sigrid Steen Haugen MOVING AND FEELING An exploration of the play between motion, emotion and motivation in yoga practitioners in Norway. Master's thesis in Religious Studies Supervisor: Gabriel Levy & Sven Bretfeld Trondheim, September 2016 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Faculty of Humanities Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 5 1.1.1 Reflexivity .............................................................................................................................. 8 1.1.2 Methods approach ................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 EXPLAINING THE TERMS ................................................................................................... -

Resource Guide for New Yoga Teachers by Zach Beach

Resource Guide for New Yoga Teachers By Zach Beach www.zachbeach.com The “I’m a yoga teacher now” Checklist ❏ Make your website - it can be super simple at first, just get something up ASAP ❏ Begin a social media presence - Start a blog, Instagram, Facebook page, or Youtube channel. Commit to one or two main ways to connect with your audience. If you start generating content now, not only will it snowball into success in the future, but you will also get better at it as time goes on. ❏ Buy Liability Insurance for yoga teachers - Google it, get it. ❏ Write your 300 word bio and memorize your 30-sec elevator speech - who you are and what you offer, for when you are meeting with a studio owner or other interested party. ❏ Take some photos - All you need is 3-5 awesome photos of yourself: One headshot, one studio shot, and one awesome yoga shot to send to anybody for anything. ❏ (Optional) Get your CPR certification and register with Yoga Alliance - You might need these to work at certain places. Design and Promote your stuff ● http://canva.com/ for designing your own flyers and promo material ● http://pixlr.com/ for modifying your photos online ● www.createspace.com, https://www.wix.com/, Weebly, or https://wordpress.com/ to make your website ● Fiverr is really great to find freelancers, you can also try 99designs, https://www.awesomeweb.com/, and Upwork ● Mailchimp or ConstantContact for your email list Stay in touch with me ● Email: [email protected] ● Website: www.zachbeach.com ● Love School: http://www.the-heart-center.com/ ● Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/zachbeachlove ● Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/zachbeachlove/ ● Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/user/zjb407/videos ● Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/user/zachbeach Websites that can help you run things and find opportunities Some of these websites take commissions, it’s usually worth it since getting people to come is the hardest part of running anything. -

WHO IS YOGA? the Will to Ignorance Ranko Bon Motovun, Istria February

WHO IS YOGA? The Will to Ignorance Ranko Bon Motovun, Istria February 2016 To Yogani, who has undertaken a worldwide experiment to find out whether books can provide the means necessary to tread the path to enlightenment It is not enough that you understand in what ignorance man and beast live; you must also have and acquire the will to ignorance. You need to grasp that without this kind of ignorance life itself would be impossible, that it is a condition under which alone the living thing can preserve itself and prosper: a great, firm dome of ignorance must encompass you. From Friedrich Nietzsche’s The Will to Power, New York: Vintage Books, 1968, p. 328. 2 PREFACE (February 8, 2016) Yoga is everywhere nowadays. Lately, it has become a staple. Who is yoga, though? It sounds like a silly question, but this selection from my Residua shows that it is no less than a crucial one, for it goes back to the origins of the spiritual quest of the human species. In time, shamanism has spawned many a path through the realm of the spirit, including yoga. As of late, these paths are marked by myriad great gurus, but underneath the august crowd is the nameless guru of us all—the animal in us. It is as old as life on earth, and it has a lot to teach us to this day. But the only way to become one with the animal in us is to abandon all thought. This accomplished, time stops and the world becomes one at long last. -

Onlineregistration Begins December 10

PRSRT STD 6930 Carroll Ave. Suite 100 U.S. POSTAGE Takoma Park MD 20912 PAID 301.270.8038 PERMIT NO 5482 willowstreetyoga.com SUBURBAN, MD Return Service Requested onlineregistration begins december 10 Bring a Friend for Free!* During our First Week (Jan 5-11) invite your friends coworkers neighbors beloveds to come try a class on us! Visit our front desk for details, or download an invitation from our website. * It's even better than free!! For each of your new-to-Willow-Street friends that registers for a class or special, we'll send you a $25 gift certificate!! willow street yoga winter/spring session 2015 january 5 – may 24 (20 weeks) Everybody Welcome. Yes, really. Everybody. Everybody welcome, with your body as-is. There is no too young, too old, too inflexible, too out-of-shape, too big, too small, too uncoordinated, too stuck-in-your-ways. Everybody welcome, whether you’re a brand-new beginner, or you’ve practiced for decades, or you’ve been pulled away from your practice by life's changes, and you’re ready to reconnect. Turn the page, find the practice that suits you, and join us. There’s no one quite like you here, and you’ll fit right in. Students! Aren't they beautiful? class schedule 4-5 nine-week specials 6-7 workshops 8-9 how to register 11 willow street yoga winter/spring session 2015 january 5 – may 24 (20 weeks) about 28 Day Meditation Challenge Willow Street Yoga Center is one of the DC area’s most renowned yoga studios, with Join us for the month of February in a commitment to a daily meditation practice.