Wild Apple Trees for Wildlife Bulletin #7126

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Brown Brothers Company [Catalog]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7877/brown-brothers-company-catalog-67877.webp)

Brown Brothers Company [Catalog]

Historic, Archive Document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. V i ’ f fowe v'|f kM W ? - . / :1? 'M tl'• .Tf? INTRODUCTION N again presenting our revised General Catalogue, we desire to assure our agents and customers, that, in the future, the same careful business policy will be continued that has in many years past enabled us to increase from the smallest of plantings to the largest area of land under nursery cultiva- tion in the country. Our customers can be found in every part of every state and territory throughout the Union. Origin.—We began in a very small way. Two Our Grounds, Cellars and Packing Depart- young men, barely out of their teens, started ments.—Our office is located in the center of life as canvassers for fruit trees and shrubs BEOWN PAEK, a delightful suburb of the city. in New York and New England. They were The park proper comprises some 15 acres, on successful salesmen through sheer force of which will be seen during the season hundreds necessity. Within two years, a room was se- of varieties of roses and plants and specimens cured in Eochester and the business launched of about all of the more common varieties of by engaging a few men to canvass nearby trees, shrubs and conifers. A few hours spent towns. A couple of years later, with the steady on these grounds during the summer season is increase of business, an office was opened in time well spent, for here you will see many nat- Chicago and a nursery started in Canada. -

How to Raise Fruits / a Hand-Book of Fruit Culture

UMASS/AMHERST "^^f 31EDbbD0S15a5'^T TO i ^^^^SIEI HOW TO KAISE FRUITS. HOW TO RAISE FRUITS. A HAND-BOOK OP FRUIT CULTURE, BEING A GUIDE TO THE PROPER Cultitetian anb Panagemeiit at Jfrmt frets, AND OF ^ GRAPES AND SMALL FRUITS, CONDENSED DESCRIPTIONS OF MANY OF THE BEST AND MOST POPULAR VARIETIES. By THOMAS GREGG. FULLY ILLUSTRATED. NEW YORK: S. R. WELLS & COMPANY, PUBLISHERS, 737 BROADWAY. 1880. 434. 2- Copyright, 1877, by 8. R. WELLS & COMPANY, — PREFACE The spirit said " Write ! " And I wrote. The re- sult is before the reader. If it shall be of any service to liini—well ; if not well. But there is hope that this little book—imperfect and faulty as a just criticism may find it to l)e—will be of some service to the fruit-eating and fruit-produc- ing public. If it shall in any wise aid those who don't now know how to choose, to plant, to cultivate, and to use the fniits of the earth, which the beneficent Cre- ator has so bounteously bestowed upon us, it will have fulfilled the mission designed for it by THE AUTHOR. yj%^^ CONTENTS. PART 1. Jfrtiit Culture in (Btixtx^l. CHAPTER T.—INTRODUCTORY REMARKS. rkua 1. The free use of Fruit as a common article of Food will greatly contribute to the Health of the People. 2. Fruit is a cheap article of Food. 3. The culture of good Fruit is profitable. 4. Fruit furnishes an amount of good living not otherwise attainable. 5. There is economy in the use of Fruit 9 CHAPTER II. -

Native Trees of Georgia

1 NATIVE TREES OF GEORGIA By G. Norman Bishop Professor of Forestry George Foster Peabody School of Forestry University of Georgia Currently Named Daniel B. Warnell School of Forest Resources University of Georgia GEORGIA FORESTRY COMMISSION Eleventh Printing - 2001 Revised Edition 2 FOREWARD This manual has been prepared in an effort to give to those interested in the trees of Georgia a means by which they may gain a more intimate knowledge of the tree species. Of about 250 species native to the state, only 92 are described here. These were chosen for their commercial importance, distribution over the state or because of some unusual characteristic. Since the manual is intended primarily for the use of the layman, technical terms have been omitted wherever possible; however, the scientific names of the trees and the families to which they belong, have been included. It might be explained that the species are grouped by families, the name of each occurring at the top of the page over the name of the first member of that family. Also, there is included in the text, a subdivision entitled KEY CHARACTERISTICS, the purpose of which is to give the reader, all in one group, the most outstanding features whereby he may more easily recognize the tree. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to the Houghton Mifflin Company, publishers of Sargent’s Manual of the Trees of North America, for permission to use the cuts of all trees appearing in this manual; to B. R. Stogsdill for assistance in arranging the material; to W. -

Fruit Production Lake Constance 7.500 Ha Apples on German Side

. Fruit production Bodensee . Research Station KOB Dr. Manfred Büchele 1 Fruit production Lake Constance 7.500 ha apples on German side KOB Production Thurgau (CH) ca. 1.800 ha Starting modern production in 1960 Production ~ 8 000 ha 1 600 growers, ca. 800 part time 250.000 – 300.000 t table fruits (25-30 % of Germany) 3 Producer organizations 75% of sales 200 - 250 Mio € sales Problems • Plant protection: Scrab, Codling moth, fire blight etc. • High investments: 40% of cultivars with hailnets Advantages • Well educated and trained farmers • Good equipment, new modern cultivars • Additional income: Tourism, direct sale, industry • Support by Government (direct: 15 - 20% of income) • Production in the middle of consumers (50% of consumption) Production varieties Jonagold Elstar Golden Delicious Braeburn Gala Rest NEU Clubsorten Idared Rest Modern production Braeburn 2nd year 3,5 m x 0,8 m 10 t/ha Modern production Red Jonaprince 4th year 3,5 m x 0,8 m 68 t/ha Production for processing Low cost production Resistant varieties 12th year 4,5 m x 2,5 m 50 t/ha Modern CA-Storage for Apples Sorting size/colour by P.O. 40 % of harvest CA-storage Fruit production Lake Constance -Organization of sale- • Ca. 75 % organized sale of fruits (P.O.) • 3 P.O. mastered by farmers but with professional staff • Delivery retail and export centralized from 1 sales office • Quality management system from farm to sales point • High quality production with modern varieties, new orchards and best storage/sorting/packing equipment • New markets (varieties, organic production) No competition between famersErfolgskennzahlen or P.O. -

Malussylvestris Family: Rosaceae Apple

Malus sylvestris Family: Rosaceae Apple Apple (Malus spp.) consists of 30+ species that occur on both sides of the Atlantic in northern temperate zones. Its wood can be confused with pear (Pyrus spp.) and other “fruitwoods” in the rose family (Rosaceae). Malus is the classical Latin name for apple. Apple hybridizes with North American crab apples. Malus angustifolia-American crab apple, buncombe crab apple, crab apple, crabtree, narrowleaf crab, narrowleaf crab apple, southern crab, southern crab apple, wild crab, wild crab apple Malus coronaria-Alabama crab, Allegheny crab, American crab, American crab apple, Biltmore crab apple, Buncombe crab, crab, crab apple, Dawson crab, Dunbar crab, fragrant crab, garland tree, lanceleaf crab apple, Missouri crab, sweet crab apple, sweet-scented crab, sweet wild crab, wild crab, wild sweet crab Malus fusca-crab apple, Oregon crab, Oregon crab apple, Pacific crab apple, western crab apple, wild crab apple Malus ioensis-Bechel crab, crab apple, Iowa crab, Iowa crab apple, prairie crab, prairie crab apple, wild crab, wild crab apple Malus sylvestris-apple, common apple, wild apple. Distribution Apple is a cultivated fruit tree, persistent, escaped and naturalized locally across southern Canada, in eastern continental United States, and from Washington south to California. Native to Europe and west Asia. Apple grows wild in the southern part of Great Britain and Scandinavia and is found throughout Europe and southwestern Asia. It is planted in most temperate climates The Tree The tree rarely reaches 30 ft (9 m), with a small crooked bole to 1 ft (0.3 m) in diameter. The Wood General Apple wood has a reddish gray heartwood and light reddish sapwood (12 to 30 rings of sapwood). -

Apple Orchard Information for Beginners

The UVM Apple Program: Extension and Research for the commercial tree fruit grower in Vermont and beyond... Our commitment is to provide relevant and timely horticultural, integrated pest management, marketing and economics information to commercial tree fruit growers in Vermont and beyond. If you have any questions or comments, please contact us. UVM Apple Team Members Dr. Lorraine Berkett, Faculty ([email protected] ) Terence Bradshaw, Research Technician Sarah Kingsley-Richards, Research Technician Morgan Cromwell, Graduate Student Apple Orchard Information for Beginners..... [The following material is from articles that appeared in the “For Beginners…” Horticultural section of the 1999 Vermont Apple Newsletter which was written by Dr. Elena Garcia. Please see http://orchard.uvm.edu/ for links to other material.] Websites of interest: UVM Apple Orchard http://orchard.uvm.edu/ UVM Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Calendar http://orchard.uvm.edu/uvmapple/pest/2000IPMChecklist.html New England Apple Pest Management Guide [use only for biological information] http://www.umass.edu/fruitadvisor/NEAPMG/index.htm Cornell Fruit Pages http://www.hort.cornell.edu/extension/commercial/fruit/index.html UMASS Fruit Advisor http://www.umass.edu/fruitadvisor/ 1/11/2007 Page 1 of 15 Penn State Tree Fruit Production Guide http://tfpg.cas.psu.edu/default.htm University of Wisconsin Extension Fruit Tree Publications http://learningstore.uwex.edu/Tree-Fruits-C85.aspx USDA Appropriate Technology Transfer for Rural Areas (ATTRA) Fruit Pages: http://www.attra.org/horticultural.html _____________________________________________________ Considerations before planting: One of the questions most often asked is, "What do I need to do to establish a small commercial orchard?" The success of an orchard is only as good as the planning and site preparation that goes into it. -

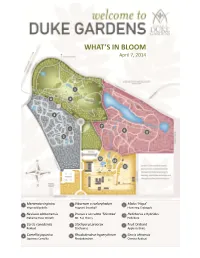

What's in Bloom

WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 5 4 6 2 7 1 9 8 3 12 10 11 1 Mertensia virginica 5 Viburnum x carlcephalum 9 Malus ‘Hopa’ Virginia Bluebells Fragrant Snowball Flowering Crabapple 2 Neviusia alabamensis 6 Prunus x serrulata ‘Shirotae’ 10 Helleborus x hybridus Alabama Snow Wreath Mt. Fuji Cherry Hellebore 3 Cercis canadensis 7 Stachyurus praecox 11 Fruit Orchard Redbud Stachyurus Apple cultivars 4 Camellia japonica 8 Rhododendron hyperythrum 12 Cercis chinensis Japanese Camellia Rhododendron Chinese Redbud WHAT’S IN BLOOM April 7, 2014 BLOMQUIST GARDEN OF NATIVE PLANTS Amelanchier arborea Common Serviceberry Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Cornus florida Flowering Dogwood Stylophorum diphyllum Celandine Poppy Thalictrum thalictroides Rue Anemone Fothergilla major Fothergilla Trillium decipiens Chattahoochee River Trillium Hepatica nobilis Hepatica Trillium grandiflorum White Trillium Hexastylis virginica Wild Ginger Hexastylis minor Wild Ginger Trillium pusillum Dwarf Wakerobin Illicium floridanum Florida Anise Tree Trillium stamineum Blue Ridge Wakerobin Malus coronaria Sweet Crabapple Uvularia sessilifolia Sessileleaf Bellwort Mertensia virginica Virginia Bluebells Pachysandra procumbens Allegheny spurge Prunus americana American Plum DORIS DUKE CENTER GARDENS Camellia japonica Japanese Camellia Pulmonaria ‘Diana Clare’ Lungwort Cercis canadensis Redbud Prunus persica Flowering Peach Puschkinia scilloides Striped Squill Cercis chinensis Redbud Sanguinaria canadensis Bloodroot Clematis armandii Evergreen Clematis Spiraea prunifolia Bridalwreath -

Handling of Apple Transport Techniques and Efficiency Vibration, Damage and Bruising Texture, Firmness and Quality

Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences Centre of Excellence AGROPHYSICS for Applied Physics in Sustainable Agriculture Handling of Apple transport techniques and efficiency vibration, damage and bruising texture, firmness and quality Bohdan Dobrzañski, jr. Jacek Rabcewicz Rafa³ Rybczyñski B. Dobrzañski Institute of Agrophysics Polish Academy of Sciences PUBLISHED BY: B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ACTIVITIES OF WP9 IN THE CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE AGROPHYSICS CONTRACT NO: QLAM-2001-00428 CENTRE OF EXCELLENCE FOR APPLIED PHYSICS IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE WITH THE th ACRONYM AGROPHYSICS IS FOUNDED UNDER 5 EU FRAMEWORK FOR RESEARCH, TECHNOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AND DEMONSTRATION ACTIVITIES GENERAL SUPERVISOR OF THE CENTRE: PROF. DR. RYSZARD T. WALCZAK, MEMBER OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES PROJECT COORDINATOR: DR. ENG. ANDRZEJ STĘPNIEWSKI WP9: PHYSICAL METHODS OF EVALUATION OF FRUIT AND VEGETABLE QUALITY LEADER OF WP9: PROF. DR. ENG. BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI, JR. REVIEWED BY PROF. DR. ENG. JÓZEF KOWALCZUK TRANSLATED (EXCEPT CHAPTERS: 1, 2, 6-9) BY M.SC. TOMASZ BYLICA THE RESULTS OF STUDY PRESENTED IN THE MONOGRAPH ARE SUPPORTED BY: THE STATE COMMITTEE FOR SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNDER GRANT NO. 5 P06F 012 19 AND ORDERED PROJECT NO. PBZ-51-02 RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF POMOLOGY AND FLORICULTURE B. DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES ©Copyright by BOHDAN DOBRZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF AGROPHYSICS OF POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES LUBLIN 2006 ISBN 83-89969-55-6 ST 1 EDITION - ISBN 83-89969-55-6 (IN ENGLISH) 180 COPIES, PRINTED SHEETS (16.8) PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER IN POLAND BY: ALF-GRAF, UL. -

A Day in the Life of Your Data

A Day in the Life of Your Data A Father-Daughter Day at the Playground April, 2021 “I believe people are smart and some people want to share more data than other people do. Ask them. Ask them every time. Make them tell you to stop asking them if they get tired of your asking them. Let them know precisely what you’re going to do with their data.” Steve Jobs All Things Digital Conference, 2010 Over the past decade, a large and opaque industry has been amassing increasing amounts of personal data.1,2 A complex ecosystem of websites, apps, social media companies, data brokers, and ad tech firms track users online and offline, harvesting their personal data. This data is pieced together, shared, aggregated, and used in real-time auctions, fueling a $227 billion-a-year industry.1 This occurs every day, as people go about their daily lives, often without their knowledge or permission.3,4 Let’s take a look at what this industry is able to learn about a father and daughter during an otherwise pleasant day at the park. Did you know? Trackers are embedded in Trackers are often embedded Data brokers collect and sell, apps you use every day: the in third-party code that helps license, or otherwise disclose average app has 6 trackers.3 developers build their apps. to third parties the personal The majority of popular Android By including trackers, developers information of particular individ- and iOS apps have embedded also allow third parties to collect uals with whom they do not have trackers.5,6,7 and link data you have shared a direct relationship.3 with them across different apps and with other data that has been collected about you. -

About Apples & Pears

Today’s program will be recorded and posted on our website and our Facebook page. https://ucanr.edu/sites/Amador_County_MGs/ Look under “Classes & Events” then “Handouts & Presentations” from our home page. Today’s handouts will also be posted here. https://www.facebook.com/UCCEAmadorMG/ Look for “Facebook Live” during the meeting or find the video link on our feed. Have a Gardening Question? UC Master Gardeners of Amador County are working by phone and email to answer your gardening questions! Phone: 209-223-6838 Email: [email protected] Facebook: @UCCEAmadorMG Not in Amador County? Find your local Master Gardener program by doing a web search for “UCCE Master Gardener” and your county name. Your Home Orchard: APPLES & PEARS by UCCE Amador County Master Gardeners John Otto & Hack Severson - October 10, 2020 To be discussed • Home Orchard Introduction • What are Apples & Pears? • History & “Lore” • Orchard Planning • Considerations for Selection • Varieties for the foothills Home Orchard Introduction 8,500’ 4,000’ 3,000’ 2,000’ 1,000’ 300’ Amador County There are a variety of fruit and nut trees grown in the Sierra Foothills but elevations and micro-climates make selection an adventure. Stone Fruits: Almond, Apricot, Cherry, Nectarine, Peach, Plumb, Prunes, Plumcots Nut Crops: Chestnuts, Filberts (Hazelnut), Pecans, Walnut, Almond (truly a stone fruit) Citrus: Lemon Lime, Orange (incl. Mandarin, Tangarine, others), Grapefruit, Kumquat, Tangelo Pome Fruits: Apple; Pear; Pomegranates; Quince “The Home Orchard”, ANR publication #3485 https://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu/Details.aspx?itemNo=3485 Apples and Pears Are?? • How are Apples and Pears different from other fruits?? • They are “Pome” fruit (also pomegranate & quince). -

Colonial Gardens Honeygold Apple

Honeygold Apple Malus 'Honeygold' Height: 20 feet Spread: 20 feet Sunlight: Hardiness Zone: 4a Description: Honeygold Apple fruit A distinctively yellowish-green apple with good, sweet Photo courtesy of University of Minnesota flavor, notably hardy, keeps well; eating apples are high maintenance and need a second pollinator; the perfect combination of accent and fruit tree, needs well-drained soil and full sun Edible Qualities Honeygold Apple is a small tree that is commonly grown for its edible qualities. It produces large yellow round apples (which are botanically known as 'pomes') with hints of red and white flesh which are usually ready for picking from mid to late fall. The apples have a sweet taste and a crisp texture. The apples are most often used in the following ways: - Fresh Eating - Cooking - Baking Features & Attributes Honeygold Apple features showy clusters of lightly-scented white flowers with shell pink overtones along the branches in mid spring, which emerge from distinctive pink flower buds. It has forest green foliage throughout the season. The pointy leaves turn yellow in fall. The fruits are showy yellow apples with hints of red, which are carried in abundance in mid fall. The fruit can be messy if allowed to drop on the lawn or walkways, and may require occasional clean-up. This is a deciduous tree with a more or less rounded form. Its average texture blends into the landscape, but can be balanced by one or two finer or coarser trees or shrubs for an effective composition. This is a high maintenance plant that will require regular care and upkeep, and is best pruned in late winter once the threat of extreme cold has passed. -

Waldo County Soil and Water Conservation District Annual Fruit Tree and Shrub Sale

Waldo County Soil and Water Conservation District Annual Fruit Tree and Shrub Sale 2018 Offerings We are returning this year with many carefully selected fruit trees, berry plants and landscape shrubs and perennials that will enhance your property’s health, natural balance, beauty and productivity. Our Landscape Plants theme this year is Wet and Dry: Beautiful Natives for Rain Gardens, Wet Areas and Shorelines. The plants offered will also tolerate drier conditions. We are also returning with popular Inside this issue plants that offer year-round color and interest, and that are good substitutes for invasive plants now Inside Story Inside Story banned. Buttonbush, at right, is a lovely shoreline Inside Story bush that can stand inundation...and also has Inside Story beautiful flowers that feed butterflies and retain their form into the winter. Important Dates 05/31 06/26 Native shrubs such as the highbush or American cranberry (at left) offer flowers, fruits and fall color that is as 07/29 attractive as invasive shrubs like burning bush or Japanese barberry. Each landscape plant we offer has been selected for multi-season interest and color as well as wildlife value. Fruit Trees and Shrubs SEMI-DWARF APPLE On MM111 rootstock – semi dwarf trees – grow 15-20’ but can be pruned to a shorter height. Hardy and quicker to bear fruit than standard trees. 1. Wolf River Apple – (Left) Huge heirloom, great for pies, making a big comeback in Maine. Disease resistant and extremely hardy. 2. Holstein Apple – Seedling of Cox Orange Pippin, but larger. Creamy, yellowish, juicy flesh is aromatic and very flavorful.