Baseline Household Survey Rajanpur 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audit Report on the Accounts of Tehsil Municipal Administrations Bahawalnagar Audit Year 2013-14

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF TEHSIL MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS BAHAWALNAGAR AUDIT YEAR 2013-14 AUDITOR GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ...................................................... i Preface .......................................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................ iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS .................................................... vii Table 1: Audit Work Statistics .............................................................................. vii Table 2: Audit Observations ................................................................................. vii Table 3: Outcome Statistics ................................................................................. viii Table 4: Irregularities pointed out .......................................................................... ix CHAPTER-1 ................................................................................................. 1 1. TEHSIL MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS, BAHAWALNAGAR ..... 1 1.1.1 Introduction: ................................................................................................ 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) .......................... 1 1.1.3 Paras of Audit Reports of Remaining TMAs for the Audit Year 2012-13 . 2 1.1.4 Brief Comments on the Status of Compliance of Audit Paras of Annex-I of Audit Report 2012-13 ............................................................................ -

Muzaffargarh

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - Muzaffargarh ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhattiwala Kherawala !Molewala Siwagwala ! Mari PuadhiMari Poadhi LelahLeiah ! ! Chanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ladhranwala Kherawala! ! ! ! Lerah Tindawala Ahmad Chirawala Bhukwala Jhang Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala ! Pehar MorjhangiMarjhangi Anwarwal!a Khairewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Wali Dadwala MuhammadwalaJindawala Faqirewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! MalkaniRetra !Shah Alamwala ! Bhindwalwala ! ! ! ! ! Patti Khar ! ! ! Dargaiwala Shah Alamwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sultanwala ! ! Zubairwa(24e6)la Vasawa Khiarewala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Jhok Bodo Mochiwala PakkaMochiwala KumharKumbar ! ! ! ! ! ! Qaziwala ! Haji MuhammadKhanwala Basti Dagi ! ! ! ! ! Lalwala Vasawa ! ! ! Mirani ! ! Munnawala! ! ! Mughlanwala ! Le! gend ! Sohnawala ! ! ! ! ! Pir Shahwala! ! ! Langanwala ! ! ! ! Chaubara ! Rajawala B!asti Saqi ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BuranawalaBuranawala !Gullanwala ! ! ! ! ! Jahaniawala ! ! ! ! ! Pathanwala Rajawala Maqaliwala Sanpalwala Massu Khanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Bhandniwal!a Josawala ! ! Basti NasirBabhan Jaman Shah !Tarkhanwala ! !Mohanawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Basti Naseer Tarkhanwala Mohanawala !Citiy / Town ! Sohbawala ! Basti Bhedanwala ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohaganwala Bhurliwala ! ! ! ! Thattha BulaniBolani Ladhana Kunnal Thal Pharlawala ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Ganjiwala Pinglarwala Sanpal Siddiq Bajwa ! ! ! ! ! Anhiwala Balochanwala ! Pahrewali ! ! Ahmadwala ! ! ! -

Initial Rapid Assessment Report for Flood in Tehsil Rojhan and Tehsil Jampur, District Rajanpur August 15 , 2013

Initial Rapid Assessment Report For Flood in Tehsil Rojhan and Tehsil Jampur, District Rajanpur August 15th, 2013 Date of Survey: Thursday 15th August 2013. Time: 10:00 hrs. – 18:00 hrs. Area assessed: Tehsil Jampur, Tehsil Rojhan – District Rajanpur. PartnerAid Rapid Assessment Team: Ishtiaq Ahmad – Program Manager. Ashar Munir - Field Finance Officer. Rajan Pur is a District of Punjab. It is located in southern Punjab. It consists of three tehsils namely Rojhan Mazari, Jam pur and Rajan Pur. In August due to the heavy rains flash floods started. Rajan Pur district is badly affected by these flash floods. In Rajan Pur flood water came from Kah Sultan and Shacher torrent (rivulet). This flood water hit the different union councils of Rajan Pur. Hundreds of houses damaged fully and partially and inhabitants sitting under open sky. The displaced people have sought shelter in streets and other public buildings in and around their chaks (villages). Thus, there is an urgent need for non food items (NFIs) including mattresses, mosquito nets, Kitchen utensils, fuel for daily cooking and hygiene kits. Yearly food stock is almost completely washed away, while livestock has suffered considerable loss. Thus affected people facing critical condition and will suffer economically for at least one whole year as their current crop is damaged at large scale. According to affectees this flood is larger than the one, some 40 years ago. 1. District Flood Emergency Department Office of the Superintendent to DCO under supervision of Flood Emergency Officer 0604-689054. 2. Tehsil Control Rooms Tehsil Jampur Office of the Tehsil Municipal Administration 0604-568997. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

World Bank Document

ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT (EA) AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK Public Disclosure Authorized PUNJAB EDUCATION SECTOR REFORMS PROGRAM-II (PESRP-II) Public Disclosure Authorized PROGRAM DIRECTOR PUNJAB EDUCATION SECTOR REFORMS PROGRAM (PESRP) SCHOOL EDUCATION DEPARTMENT GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB Tel: +92 42 923 2289~95 Fax: +92 42 923 2290 url: http://pesrp.punjab.gov.pk email: [email protected] Public Disclosure Authorized Revised and Updated for PERSP-II February 2012 Public Disclosure Authorized DISCLAIMER This environmental and social assessment report of the activities of the Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program of the Government of the Punjab, which were considered to impact the environment, has been prepared in compliance to the Environmental laws of Pakistan and in conformity to the Operational Policy Guidelines of the World Bank. The report is Program specific and of limited liability and applicability only to the extent of the physical activities under the PESRP. All rights are reserved with the study proponent (the Program Director, PMIU, PESRP) and the environmental consultant (Environs, Lahore). No part of this report can be reproduced, copied, published, transcribed in any manner, or cited in a context different from the purpose for which it has been prepared, except with prior permission of the Program Director, PESRP. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This document presents the environmental and social assessment report of the various activities under the Second Punjab Education Sector Reforms Program (PESRP-II) – an initiative of Government of the Punjab for continuing holistic reforms in the education sector aimed at improving the overall condition of education and the sector’s service delivery. -

Crop Damage Assessment Along the Indus River

0 1 0 2 K t A 0 s -P . u 1 2 g 4 n 1 u 0 io A 0 rs 0 -0 e 2 0 V 1 0 -2 L F " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " !( " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " !(" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " p " " " " " " " p " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " : " " " " " " " !( " " " " " " " " " " " y " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " b " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " d " " " " " " " " " " " " " !( " " e " " " " " " " " " " t " "" " "p " " " " " " " " " " r " !( " " " " !( " " " " !( " " " p " " " " " " " o " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " p " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " p " " " " " "" " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " u " " " " " " " " " " t " " " !( " " " S " " " . " " " " " " " " " " o " " " " " " n " " " " " " " " " " " " " " D" " p " " " nn " " " " " " " " " !( " " " " e " " " " " " " " " " " " r O " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " a M " " " " " " " " " " I " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " e " " " " " " " " " aa " " " !( !(r C " " " " " " " " I " " " " " " " " " " " " " " " e " " " " " " " " " e L " " " p" " " " " " " " h I " " " " " " " " " tt "" -

RAJANPUR.Pdf

ANNUAL POLICING PLAN FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 DISTRICT RAJANPUR District Police Officer, Rajanpur. 1 INTRODUCTION BY HEAD OF DISTRICT POLICE Planning is looking into the future with eyes of the present. Ideal planning is the foundation stone for achieving success in any field. In As per requirements of sections 32, 10(4) 80 (f) and e 92 (f) of Police Order 2002, this Annual Plan is an important step towards describing our intentions for the future. As, the geographic layout of this district is peculiar; Rajanpur police is charged with arduous responsibility of tackling dynamic & multifarious issues. Nevertheless, the crime pattern in Rajanpur is quite varied. It includes important factors, as infiltration of Bugti criminals from Western side and activities of notorious gangs residing in bed of the River Indus on the Eastern Side has been remained challenge for the local police. The protection of Indus Highway which is main artery in the context of safe traveling of the commuters requires arduous days and sleepless nights. Besides this, provision of security to the foreigners visiting this district for various purposes i.e construction work on Mega Projects like Katchi Canal; constitute extremely important responsibility of Rajanpur Police. Before going ahead, it would be expedient to highlight the historical background of Rajanpur. Study of history reveals that the fort of Harrand was constructed by Hindu “Raja Harnacus” and his son “Lok Bhagat” on the style of Mohenjo-Daro that is the reason, structure of Harrand Fort seems contemporaneous civilization of Mohenjo- Daro. Study of history also reveals that Muslim rulers from Muhammad Bin Qasim to Ahmed Shah Abdali had maintained their sovereignty at this area. -

Spatio-Temporal Flood Analysis Along the Indus River, Sindh, Punjab

p !( !( 23 August 2010 !( FL-2010-000141-PAK S p a t i o - Te m p o r a l F!( lo o d A n a l y s i s a l o n g t h e I n d u s R i v e r, S i n d h , P u n j a b , K P K a n d B a l o c h i s t a n P r o v i n c e s , P a k i s t a n p Version 1.0 !( This map shows daily variation in flo!(od water extent along the Indus rivers in Sindph, Punjab, Balochistan and KPK Index map CHINA p Crisis Satellite data : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map Scale for 1:1,000,000 Map prepared by: Supported by: provinces based on time-series MODIS Terra and Aqua datasets from August 17 to August 21, 2010. Resolution : 250m Legend 0 25 50 100 AFGHANISTAN !( Image date : August 18-22, 2010 Result show that the flood extent isq® continously increasing during the last 5 days as observed in Shahdad Kot Tehsil p Source : NASA Pre-Flood River Line (2009) Kilometres of Sindh and Balochistan provinces covering villages of Shahdad, Jamali, Rahoja, Silra. In the Punjab provinces flood has q® Airport p Pre-flood Image : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map layout designed for A1 Printing (36 x 24 inch) !( partially increased further in Shujabad Tehsil villages of Bajuwala Ti!(bba, Faizpur, Isanwali, Mulana)as. Over 1000 villages !( ® Resolution : 250m Flood Water extent (Aug 18) p and 100 towns were identified as severly affepcted by flood waters and vanalysis was performed using geospatial database ® Heliport !( Image date : September 19, 2009 !( v !( Flood Water extent (Aug 19) ! received from University of Georgia, google earth and GIS data of NIMA (USGS). -

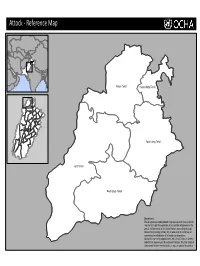

Reference Map

Attock ‐ Reference Map Attock Tehsil Hasan Abdal Tehsil Punjab Fateh Jang Tehsil Jand Tehsil Pindi Gheb Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. Bahawalnagar‐ Reference Map Minchinabad Tehsil Bahawalnagar Tehsil Chishtian Tehsil Punjab Haroonabad Tehsil Fortabbas Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted line represents approximately the Line of Control in Jammu and Kashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The final status of Jammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties. p Bahawalpur‐ Reference Map Hasilpur Tehsil Khairpur Tamewali Tehsil Bahawalpur Tehsil Ahmadpur East Tehsil Punjab Yazman Tehsil Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

1951-81 Population Administrative . Units

1951- 81 POPULATION OF ADMINISTRATIVE . UNITS (AS ON 4th FEBRUARY. 1986 ) - POPULATION CENSUS ORGANISATION ST ATIS TICS DIVISION GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN PREFACE The census data is presented in publica tions of each census according to the boundaries of districts, sub-divisions and tehsils/talukas at the t ime of the respective census. But when the data over a period of time is to be examined and analysed it requires to be adjusted fo r the present boundaries, in case of changes in these. It ha s been observed that over the period of last censuses there have been certain c hanges in the boundaries of so me administrative units. It was, therefore, considered advisable that the ce nsus data may be presented according to the boundary position of these areas of some recent date. The census data of all the four censuses of Pakistan have, therefore, been adjusted according to the administ rative units as on 4th February, 1986. The details of these changes have been given at Annexu re- A. Though it would have been preferable to tabulate the whole census data, i.e., population by age , sex, etc., accordingly, yet in view of the very huge work involved even for the 1981 Census and in the absence of availability of source data from the previous three ce nsuses, only population figures have been adjusted. 2. The population of some of the district s and tehsils could no t be worked out clue to non-availability of comparable data of mauzas/dehs/villages comprising these areas. Consequently, their population has been shown against t he district out of which new districts or rehsils were created. -

Punjab Health Statistics 2019-2020.Pdf

Calendar Year 2020 Punjab Health Statistics HOSPITALS, DISPENSARIES, RURAL HEALTH CENTERS, SUB-HEALTH CENTERS, BASIC HEALTH UNITS T.B CLINICS AND MATERNAL & CHILD HEALTH CENTERS AS ON 01.01.2020 BUREAU OF STATISTICS PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT BOARD GOVERNMENT OF THE PUNJAB, LAHORE www.bos.gop.pk Content P a g e Sr. No. T i t l e No. 1 Preface I 2 List of Acronym II 3 Introduction III 4 Data Collection System IV 5 Definitions V 6 List of Tables VI 7 List of Figures VII Preface It is a matter of pleasure, that Bureau of Statistics, Planning & Development Board, Government of the Punjab has took initiate to publish "Punjab Health Statistics 2020". This is the first edition and a valuable increase in the list of Bureau's publication. This report would be helpful to the decision makers at District/Tehsil as well as provincial level of the concern sector. The publication has been formulated on the basis of information received from Director General Health Services, Chief Executive Officers (CEO’s), Inspector General (I.G) Prison, Auqaf Department, Punjab Employees Social Security, Pakistan Railways, Director General Medical Services WAPDA, Pakistan Nursing Council and Pakistan Medical and Dental Council. To meet the data requirements for health planning, evaluation and research this publication contain detailed information on Health Statistics at the Tehsil/District/Division level regarding: I. Number of Health Institutions and their beds’ strength II. In-door & Out-door patients treated in the Health Institutions III. Registered Medical & Para-Medical Personnel It is hoped that this publication would prove a useful reference for Government departments, private institutions, academia and researchers. -

Spatio-Temporal Flood Analysis Along the Indus River, Sindh, Punjab, KPK and Balochistan Provinces, Pakistan Version 1.0

21 August 2010 FL-2010-000141-PAK Spatio-Temporal Flood Analysis along the Indus River, Sindh, Punjab, KPK and Balochistan Provinces, Pakistan Version 1.0 This map shows daily variation in flood water extent along the Indus rivers in Sindh, Punjab, Balochistan and KPK Index map CHINA Crisis Satellite data : MODIS Terra / Aqua Map Scale for 1:1,000,000 Map prepared by: Supported by: provinces based on time-series MODIS Terra and Aqua datasets from August 17 to August 21, 2010. Resolution : 250m Legend AFGHANISTAN Image date : August 17-21, 2010 025 50 100 Result show that the flood extent is continously increasing during the last 5 days as observed in Shahdad Kot Tehsil Source : NASA of Sindh and Balochistan provinces covering villages of Shahdad, Jamali, Rahoja, Silra. In the Punjab provinces flood has Pre-Flood River Line (2009) ® Kilometres Pre-flood Image : MODIS Terra / Aqua q Airport Map layout designed for A1 Printing (36 x 24 inch) partially increased further in Shujabad Tehsil villages of Bajuwala Tibba, Faizpur, Isanwali, Mulana)as. Over 1000 villages Resolution : 250m Flood Water extent (Aug 17) and 100 towns were identified as severly affected by flood waters and analysis was performed using geospatial database v® Heliport Image date : September 19, 2009 Flood Water extent (Aug 18) received from University of Georgia, google earth and GIS data of NIMA (USGS). Approx. 800 kilometres stretch of Source : NASA p ! Villages/towns PAKISTAN national highway and link roads are submerged or partially inundated by flood water. Flood Water extent (Aug 19) Major airfield Railways IRAN INDIA Baseline Imagery : MODIS Aqua Aug 19, 2010 Ri vers ± Source : NASA Flood Water extent (Aug 20) p Minor airport Rural road Urbanized area This analysis also used Pre river line MODIS data for September 19, 2009 to show identify flood water only.