Tom Brady; Drew Brees; Vincent Jackson; Ben Leber; Logan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Patriots Return to Gillette Stadium to Face Green Bay

THE PATRIOTS RETURN TO GILLETTE STADIUM TO FACE GREEN BAY MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (11-2) vs. GREEN BAY PACKERS (8-5) WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 15 Sun., Dec. 19, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 8:20 p.m. EST 10:15-12:15 Media Check-In The New England Patriots clinched a playoff berth with their 36-7 victory against 11:15-12:00 Open Locker Room Chicago last week. This week, the Patriots will return to Gillette Stadium for the 11:15-11:25 Tom Brady Availability second of two straight games against the NFC North when they host the Green Bay 12:15-12:30 Bill Belichick Press Conference Packers on Sunday Night Football. The Patriots improved to an NFL-best 31-5 record Approx. 1:05 Local Media Access to Practice in December since 2002 with the win over the Bears. 2:15 Green Bay Player Conf. Call BROADCAST INFORMATION 2:20 Mike McCarthy Conf. Call TELEVISION: This week’s game will be broadcast to a national audience by NBC THURSDAY, DECEMBER 16 and can be seen in Boston on WHDH-TV Channel 7. Al Michaels will handle play- 10:15-11:30 Media Check-In by-play duties with Cris Collinsworth providing color. Andrea Kremer will be the 11:15-12:00 Open Locker Room sideline reporter. Approx. 1:05 Local Media Access to Practice NATIONAL RADIO: This week's game will be broadcast to a national audience by FRIDAY, DECEMBER 17 Westwood One. Dave Sims and James Lofton will call the game. Hub Arkush 10:00-10:45 Media Check-In will work the sidelines. -

2011 Topps Football 2011 Complete Set Hobby Edition

2011 TOPPS FOOTBALL 2011 COMPLETE SET HOBBY EDITION All 440 Base Cards including 110 Rookies from 2011 Topps Football BASE CARDS • 440 • Veterans: 262 NFL pros. • Rookies: 110 hopeful talents. • All-Pro: 2010 NFL First Team All-Pros. • Team Cards: 32 cards featuring each team in the league. • Rookie Premiere: 30 elite 2011 NFL Rookies pose for a HOBBY STORE BENEFITS team photo. • Appeals to Fans & Collectors! • Record Breakers: They made the record book in 2010. • Outstanding Value at a Great Price! • Super Bowl Champions: The Packers and the • Collectors Return Year After Year! Lombardi Trophy! • Ships September - The Start of the NFL Season! • League MVP: Tom Brady • 2010 Rookies Of The Year: Sam Bradford & Ndamukong Suh ® TM & © 2011 The Topps Company, Inc. Topps and Topps Football are trademarks of The Topps Company, Inc. All rights reserved. © 2011 NFL Properties, LLC. Team Names/Logos/Indicia are trademarks of the teams indicated. All other PLUS One 5-Card Pack of Hobby Exclusive NFL-related trademarks are trademarks of the National Football League. Officially Licensed Product of NFL PLAYERS | NFLPLAYERS.COM. Please note that you must obtain the approval of the National Football League Properties in promotional materials that incorporate any marks, designs, logos, etc. of the National Football League or any of its teams, unless the Numbered* Red Base Parallel Cards material is merely an exact depiction of the authorized product you purchase from us. Topps does not, in any manner, make any representations as to whether its cards will attain any future value. NO PURCHASE NECESSARY. PLUS ONE 5-CARD PACK OF HOBBY EXCLUSIVE NUMBERED RED BASE PARALLEL CARDS 2011 COMPLETE SET CHECKLIST 1 Aaron Rodgers 69 Tyron Smith 137 Team Card 205 John Kuhn 273 LeGarrette Blount 341 Braylon Edwards 409 D.J. -

Patriots Host Ravens in Wild Card Playoff Game

PATRIOTS HOST RAVENS IN WILD CARD PLAYOFF GAME MEDIA SCHEDULE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-6) vs. BALTIMORE RAVENS (9-7) WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 6 Sunday, Jan. 10, 2010 ¹ Gillette Stadium (68,756) ¹ 1:00 p.m. EDT 10:50 -11:10 a.m. Bill Belichick Press Conference The 2009 AFC East Champion New England Patriots will host the Baltimore Ravens in 11:10 -11:55 a.m. Open Locker Room a Wild Card playoff matchup this Sunday. The Patriots have won 11 consecutive 11:10-11:20 p.m. Tom Brady Availability home playoff games and have not lost at home in the playoffs since Dec. 31, 1978. 11:30 a.m. Ray Lewis Conf. Calls The Patriots closed out the 2009 regular-season home schedule with a perfect 8-0 1:05 p.m. Practice Availability record at Gillette Stadium. The first three times the Patriots went undefeated at TBA John Harbaugh Conf. Call home in the regular-season (2003, 2004 and 2007) they advanced to the Super THURSDAY, JANUARY 7 Bowl. 11:10 -11:55 p.m. Open Locker Room HOME SWEET HOME Approx. 1:00 p.m. Practice Availability The Patriots are 11-1 at home in the playoffs in their history and own an 11-game FRIDAY, JANUARY 8 home winning streak in postseason play. Eleven of the franchise’s 12 home playoff 11:30 a.m. Practice Availability games have taken place since Robert Kraft purchased the team 16 years ago. 1:15 -2:00 p.m. Open Locker Room PATRIOTS AT HOME IN THE PLAYOFFS (11-1) 2:00-2:15 p.m. -

Good Signs, Bad Signs

C M Y K D7 DAILY 10-28-07 MD BD D7 CMYK The Washington Post x B Sunday, October 28, 2007 D7 RedskinsGameday By Gene Wang 1 REDSKINS (4-2) VS. PATRIOTS (7-0) 4:15 P.M. AT GILLETTE STADIUM » TV: WTTG-5, WBFF-45 » RADIO: WWXX (92.7 FM), WWXT (94.3 FM), WBIG (100.3 FM), WXTR (730 AM) » LINE: Patriots by 16 ⁄2 REDSKINS ROSTER FIRST DOWN SECOND DOWN THIRD DOWN FOURTH DOWN PATRIOTS ROSTER No. Player Pos. Ht. Wt. Ball Control Rough Up Randy Pressure Brady Crowd Control No. Player Pos. Ht. Wt. 4 Derrick Frost P 6-4 208 The Patriots have perhaps the NFL’s Wide receiver Randy Moss is in the Patriots quarterback Tom Brady has The fans at Gillette Stadium are going 3 Stephen Gostkowski PK 6-1 210 6 Shaun Suisham PK 6-0 205 best passing attack, so it will be midst of a career resurgence since thrown 27 touchdown passes and two to be charged up to see their team at 6 Chris Hanson P 6-2 202 8 Mark Brunell QB 6-1 217 important for the Redskins to win time joining the Patriots in the offseason. interceptions thanks to plenty of time home for the first time in three weeks. 7 Matt Gutierrez QB 6-4 230 15 Todd Collins QB 6-4 228 of possession and keep New England’s Moss has caught passes in double- in the pocket. Brady has been sacked The Patriots played their past two 10 Jabar Gaffney WR 6-1 200 17 Jason Campbell QB 6-5 233 offense off the field. -

Week 7 Injury Report -- Friday

FOR USE AS DESIRED NFL-PER-7B 10/20/06 WEEK 7 INJURY REPORT -- FRIDAY Following is a list of quarterback injuries for Week 7 Games (October 22-23): Cincinnati Bengals Out Anthony Wright (Appendix) Kansas City Chiefs Out Trent Green (Head) Oakland Raiders Out Aaron Brooks (Right Shoulder) Tampa Bay Buccaneers Out Chris Simms (Splenectomy) Miami Dolphins Doubtful Daunte Culpepper (Knee) Jacksonville Jaguars Questionable Byron Leftwich (Ankle) Atlanta Falcons Probable Michael Vick (Right Shoulder) Minnesota Vikings Probable Tarvaris Jackson (Knee) New England Patriots Probable Tom Brady (Right Shoulder) New York Jets Probable Chad Pennington (Calf) Following is a list of injured players for Week 7 Games: JACKSONVILLE JAGUARS AT HOUSTON TEXANS Jacksonville Jaguars OUT WR Matt Jones (Hamstring); T Stockar McDougle (Ankle); DT Marcus Stroud (Ankle) QUESTIONABLE CB Terry Cousin (Groin); QB Byron Leftwich (Ankle); DE Marcellus Wiley (Groin) PROBABLE S Donovin Darius (Knee); RB Maurice Jones-Drew (Foot); G Chris Naeole (Knee); S Nick Sorensen (Calf); WR Reggie Williams (Shoulder) Listed players who did not participate in ''team'' practice: (Defined as missing any portion of 11-on-11 team work) WED Stockar McDougle; Marcus Stroud; Matt Jones THURS Marcus Stroud; Matt Jones; Stockar McDougle; Terry Cousin; Donovin Darius FRI Matt Jones; Stockar McDougle; Marcus Stroud; Terry Cousin; Byron Leftwich Houston Texans QUESTIONABLE DE Jason Babin (Back); S Glenn Earl (Neck); DE Antwan Peek (Hamstring); TE Jeb Putzier (Foot); T Zach Wiegert (Knee) PROBABLE -

Falcons Offense Falcons Specialists Falcons

vs. SUNDAY, September 29, 2013 - Georgia Dome 2 Matt Ryan ..................................... QB FALCONS OFFENSE FALCONS DEFENSE 3 Stephen Gostkowski ........................ K 3 Matt Bryant ...................................... K 6 Ryan Allen ....................................... P WR 11 Julio Jones 83 Harry Douglas 15 Kevin Cone RE 50 Osi Umenyiora 99 Stansly Maponga 4 Dominique Davis ........................... QB 11 Julian Edelman............................. WR LT 72 Sam Baker 73 Ryan Schraeder 65 Jeremy Trueblood DT 91 Corey Peters 94 Peria Jerry 5 Matt Bosher ..................................... P 12 Tom Brady .................................... QB LG 63 Justin Blalock 69 Harland Gunn DT 95 Jonathan Babineaux 92 Travian Robertson 11 Julio Jones .................................. WR 15 Ryan Mallett .................................. QB C 66 Peter Konz 61 Joe Hawley 15 Kevin Cone ................................... WR LE 96 Jonathan Massaquoi 98 Cliff Matthews 93 Malliciah Goodman 17 Aaron Dobson .............................. WR RG 75 Garrett Reynolds 69 Harland Gunn 19 Drew Davis .................................. WR OLB 59 Joplo Bartu 53 Omar Gaither 18 Matthew Slater ............................. WR RT 76 Lamar Holmes 73 Ryan Schraeder 65 Jeremy Trueblood 21 Desmond Trufant .......................... CB MLB 52 Akeem Dent 55 Paul Worrilow 22 Stevan Ridley ................................ RB TE 88 Tony Gonzalez 86 Chase Coffman 80 Levine Toilolo 22 Asante Samuel .............................. CB OLB 54 Stephen Nicholas 51 -

Final Rosters

Rosters 2001 Final Rosters Injury Statuses: (-) = OK; P = Probable; Q = Questionable; D = Doubtful; O = Out; IR = On IR. Baltimore Hownds Owner: Zack Wilz-Knutson PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. Houston Stallions Owner: Ian Wilz PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR Dave Brown QB ARI - Jake Plummer QB ARI - Tim Couch QB CLE - Duce Staley RB PHI - Ricky Watters RB SEA IR Ron Dayne RB NYG - Stanley Pritchett RB CHI - Zack Crockett RB OAK - Derrick Mason WR TEN - Johnnie Morton WR DET - Laveranues Coles WR NYJ - Willie Jackson WR NOR - Alge Crumpler TE ATL - Dave Moore TE TAM - Matt Stover K BAL - Paul Edinger K CHI - 2001 Final Rosters 1 Rosters Chicago Bears Defense CHI - Pittsburgh Steelers Defense PIT - Carolina Panthers Special Team CAR - Dallas Cowboys Special Team DAL - Dan Reeves Head Coach ATL - Dick Jauron Head Coach CHI - NYC Dark Force Owner: D.J. Wendell NFL ON PLAYER POSITION INJ STARTER RESERVE TEAM IR Aaron Brooks QB NOR - Daunte Culpepper QB MIN - Jeff Blake QB NOR - Bob Christian RB ATL - Emmitt Smith RB DAL - James Stewart RB DET - Jim Kleinsasser RB MIN - Warrick Dunn RB TAM - Cris Carter WR MIN - James Thrash WR PHI - Jerry Rice WR OAK - Travis Taylor WR BAL - Dwayne Carswell TE DEN - Jay Riemersma TE BUF - Jay Feely K ATL - Joe Nedney K TEN - San Francisco 49ers Defense SFO - Defense TAM - 2001 Final Rosters 2 Rosters Tampa Bay Buccaneers Minnesota Vikings Special Team MIN - Oakland Raiders Special Team OAK - Dick Vermeil Head Coach KAN - Steve Mariucci Head Coach SFO - Las Vegas Owner: ?? PLAYER POSITION NFL TEAM INJ STARTER RESERVE ON IR There are no players on this team's week 17 roster. -

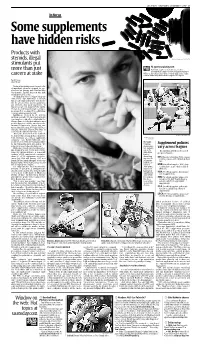

Somesupplements Havehiddenrisks

USA TODAY · WEDNESDAY,DECEMBER5,2007 · 3C In focus Some supplements have hidden risks Products with steroids, illegal By Sean Dougherty, USA TODAY stimulants put At sports.usatoday.com more than just If you take supplements, how concerned are you that they contain steroids or illegal stimulants? careers at stake Will you stop taking them? Share your thoughts in the online version of this story and read the complete HFL report. By A.J. Perez USA TODAY Obafemi Ayanbadejo went through a list of ingredients when he shopped for sup- plements last January and found nothing objectionable. An NFL drug test later that month proved otherwise. “A failed drug test is a bigger black eye than a DUI,” says Ayanbadejo, a fullback and special teams player who tested posi- tive for a form of the steroid nandrolone and received a four-game suspension. “In my case, people ran away from me saying, ‘He failed a test for performance-enhanc- ing drugs. He’s cheating. He’s really trying to get an advantage on the field.’ ” Ayanbadejo, released by the Arizona Cardinals soon after the failed tests and still searching for a club after a stint with the Chicago Bears, isn’t the first athlete to say a positive drug test could be traced to a con- taminated supplement. Tampa Bay out- fielder Alex Sanchez in 2005 and San Diego Chargers linebacker Shawne Merriman in 2006 said the same after positive tests. “It became answer 1-A in the textbook for athletes who got pinched in a drug test: By Elaine Thompson, AP Point the finger at a dietary supplement By Mike Buscher company,” says Daniel Fabricant, vice for USA TODAY president of scientific and regulatory affairs No team: for the Natural Products Association. -

Printable Commercialization Training Camp Speakers

National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA’s Commercialization Training Camp Speaker Roster Obafemi Ayanbadejo Founder of Health Reel NFL Veteran and Super Bowl Champion Obafemi Devin Ayanbadejo is a former American professional football running back, fullback, and special teams player. His professional football career began as an undrafted free agent in 1997 with the Minnesota Vikings. He played college football at San Diego State where he also earned his BA in Psychology. He also played for the Baltimore Ravens (1999-2002), Miami Dolphins (2002-2003), Arizona Cardinals 2004-2007), Chicago Bears (2007) and California Redwoods (2009) of the UFL. Ayanbadejo was a member and signicant contributor on the 2000 Ravens Super Bowl XXXV championship team. He ocially retired from professional football in January, of 2010. Since retiring from professional football, Ayanbadejo has earned his MBA from Johns Hopkins Carey School of business in Baltimore, MD. He has held founding and executive positions in several businesses and startups, including a startup based on technology exclusively licensed from the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. AQ Digital Health Institute, founded by Ayanbadejo, is presently working to commercialize a mobile health and tness technology that uses articial intelligence (A.I.) and neural networks to turn your smart phone into a device that can deliver customized health and tness data in less than 3 minutes by calculating body composition and its eect on metabolic burn rate and its correlation to health and disease risk. Anne A. Balduzzi Director, Advisory Services TEDCO Anne Balduzzi has decades of technology expertise. Prior to joining TEDCO, her background included product development and marketing roles at Apple, AOL (when it was a start-up), and Viewtron, the rst consumer online service in North America. -

Broncos Defense Broncos Offense Broncos

65605_Broncos 9-24-06 9/21/06 4:41 PM Page 1 NEW ENGLAND New England Patriots (2 - 0) vs. Denver Broncos (1 - 1) DENVER # NAME ..................POS Sunday, September 24, 2006 ★ 8:15 p.m. ★ Gillette Stadium # NAME ..................POS 3 Stephen Gostkowski ..K 1 Jason Elam................K 8 Josh Miller ................P 3 Paul Ernster............P/K 12 Tom Brady ..............QB PATRIOTS OFFENSE PATRIOTS DEFENSE 6 Jay Cutler ..............QB 16 Matt Cassel ............QB 11 Quincy Morgan ......WR WR: 87 Reche Caldwell 85 Doug Gabriel LE: 94 Ty Warren 99 Mike Wright 91 Marquise Hill 17 Chad Jackson ........WR 14 Todd Devoe............WR 21 Randall Gay ............CB LT: 72 Matt Light 65 Wesley Britt NT: 75 Vince Wilfork 96 Johnathan Sullivan* 90 Le Kevin Smith* 15 Brandon Marshall....WR 22 Asante Samuel ........CB LG: 70 Logan Mankins 64 Gene Mruczkowski* RE: 93 Richard Seymour 97 Jarvis Green 16 Jake Plummer ........QB 23 Willie Andrews ........DB C: 67 Dan Koppen 71 Russ Hochstein OLB: 59 Rosevelt Colvin 58 Pierre Woods* 20 Mike Bell ................RB 25 Artrell Hawkins ........DB RG: 61 Stephen Neal 71 Russ Hochstein ILB: 54 Tedy Bruschi 53 Larry Izzo 52 Eric Alexander 21 Hamza Abdullah ........S 26 Eugene Wilson ........DB RT: 68 Ryan O'Callaghan 77 Nick Kaczur* 22 Domonique Foxworth..CB ILB: 55 Junior Seau 51 Don Davis 27 Ellis Hobbs ..............CB TE: 84 Benjamin Watson 45 Garrett Mills* 24 Champ Bailey ..........CB OLB: 50 Mike Vrabel 95 Tully Banta-Cain 28 Corey Dillon ............RB TE: 82 Daniel Graham 86 David Thomas 25 Nick -

Home Away April 23, at 5 P.M

the 2020 nfl draft 2020 opponents The 85th National Football League Draft will begin on Thursday, home away April 23, at 5 p.m. PT. It will serve as three-day virtual fundraiser Atlanta Falcons Buffalo Bills befitting charities that are battling the spread of COVID-19. Carolina Panthers Cincinnati Bengals Denver Broncos Denver Broncos The Los Angeles Chargers enter the 2020 NFL Draft with seven Jacksonville Jaguars Kansas City Chiefs selections — one in each round. The team is slated to kick off its Kansas City Chiefs Las Vegas Raiders selections at No. 6. Las Vegas Raiders Miami Dolphins New England Patriots New Orleans Saints The 2020 NFL Draft will mark General Manager Tom Telesco's New York Jets Tampa Bay Buccaneers eighth with the team. Since joining the team in 2013, Telesco has drafted five players that eventually made a Pro Bowl with the team, including three who did so multiple times. Wide receiver quick facts of the draft Keenan Allen, who was the team's third-round selection in Schedule: DAY DATE START TIME ROUNDS Telesco's inaugural draft with the Bolts, has been to three-straight 1 Thursday, April 23 5 p.m. PT 1 Pro Bowls. Safety Derwin James Jr., and defensive back Desmond 2 Friday, April 24 4 p.m. PT 2-3 King II are the two players Telesco has drafted to earn first-team 3 Saturday, April 25 9 a.m. PT 4-7 All-Pro recognition from The Associated Press. Television: NFL Network, ESPN and ABC will televise the draft Teams have 10 minutes to select and player in the first round and on all three days. -

Patriots Football Network

PAT RIOTS VS . BROW NS SERIES HISTORY BILL B ELICHICK IN CLEVELAND The Patriots and Browns will meet for Patri ots Head Coach Bill Belichick was the head c oach of the the 22nd time overall when the clubs Cleve land Browns for five seasons fr om 1991-95. Be lichick took square off on Su nday. over with the Browns comin g off of what was their w orst season The Patriots have won the last four in fra nchise history, a 3-13 campai gn in 1990. By 199 4, Belichick games datin g b ack to 2001. had coached the Bro wns to an 11-5 record and a pl ayoff berth. Cleveland lea ds the all-time s eries with The Browns’ 11 victo ries in 1994 are tied for the sec ond highest a 12-9 mark, i ncludin g one p ostseason sin gle-season win tot al in the history of the franchis e, and their game when th e Bill Belichick-le d Browns claime d a 20-13 victor y playo ff victory over the Patriots in the wild card round that over the Patriot s on New Year’s Day, 1995 in a Wild Card Playo ff seas on stands as th e franchise’s m ost recent play off win. In game at Clevela nd’s Municipal St adium. 1994 , the Browns all owed just 204 points – the fe west points The Patriots and Browns pla yed five times i n a si x-year spa n allow ed in the NFL th at season and t he fewest points allowed by from 1999-200 4 and then wen t three season s before the las t a def ense coached b y Belichick.