Florida State University Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nickelodeon Grants Kids' Wishes with a Brand-New Season of Hit Animated Series the Fairly Oddparents Saturday, May 4, at 9:30 A.M

Nickelodeon Grants Kids' Wishes With A Brand-New Season Of Hit Animated Series The Fairly OddParents Saturday, May 4, At 9:30 A.M. (ET/PT) BURBANK, Calif., April 25, 2013 /PRNewswire/ -- Nickelodeon will premiere its ninth season of the Emmy Award-winning animated series, The Fairly OddParents, on Saturday, May 4, at 9:30 a.m. (ET/PT). The Fairly OddParents follows the magical adventures of 10-year-old Timmy Turner and his well-meaning fairy godparents who grant him wishes. After 12 years on the air, The Fairly OddParents continues to rank among the network's top programs and reached more than 20 million K2-11 in 1Q13. The Fairly OddParents will air regularly on Saturdays at 9:30 a.m. (ET/PT) on Nickelodeon. (Photo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20130425/NY02132) "The Fairly OddParents exemplifies what has made Nickelodeon a leader in animation - innovative, amazingly funny, creator- driven content," said Russell Hicks, President of Content Development and Production. "Kids have fallen in love with the magical world Butch Hartman has created and we are delighted to serve up a new season filled with fun and entertaining adventures for our audience." The Fairly OddParents follows the comedic adventures of Timmy Turner, a 10-year-old boy who overcomes typical kid obstacles with the help of his wand-wielding wish-granting fairy godparents, Cosmo and Wanda. These wishes fix problems that include everything from an aggravating babysitter to difficult homework assignments. With their eagerness to help Timmy, Cosmo and Wanda always succeed in messing things up. In the season nine premiere, "Turner & Pooch," Mr. -

C5348 : Color Pixter® the Fairly Odd Parents Software

C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 1 Owner’s Manual Model Number: C5348 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 2 2 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 3 Let’s Go! Before inserting a software cartridge, turn power off! Insert the software cartridge into the software port.Turn power back on. Software Cartridge Software Port • Some of the tools on the tool menu are not available for use in some games or activities. If a tool is not available for use, you will hear a tone. • Please keep this manual for future reference, as it contains important information. IMPORTANT! If the tip of the stylus and the image on screen do not align, it’s time to calibrate them! Please refer to page 39, Calibrating the Stylus. 3 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 4 The Fairly OddParents™ Create & Play! Choose an activity or game from the Home Screen: Magic Art Studio, Cast a Spell, Sewer Search, Catch a Falling Star and Yucky Food Transformer. Touch the activity or game on the screen with the stylus. Magic Art Studio Cast a Spell Sewer Search Catch a Falling Star Yucky Food Transformer 4 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 5 Magic Art Studio Object: Create a FairlyOdd™ Masterpiece! • First, you need to choose a starter background. • Touch the arrows on the bottom of the screen with the stylus to scroll through different backgrounds. • When you find one that you like, touch your choice on the screen with the stylus. -

Securities and Exchange Commission Form 10-Q

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q ☒ QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the quarterly period ended March 31, 2002 OR o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 1-9553 VIACOM INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 04-2949533 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 1515 Broadway, New York, New York 10036 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (212) 258-6000 Registrant's telephone number, including area code Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15 (d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days Yes ☒ No o. Number of shares of Common Stock Outstanding at April 30, 2002: Class A Common Stock, par value $.01 per share—137,292,877 Class B Common Stock, par value $.01 per share—1,630,244,665 VIACOM INC. INDEX TO FORM 10-Q Page PART I—FINANCIAL INFORMATION Item 1. Financial Statements. Consolidated Statements of Operations (Unaudited) for the Three Months ended March 31, 2002 and March 31, 2001 3 Consolidated Balance Sheets at March 31, 2002 (Unaudited) and December 31, 2001 4 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows (Unaudited) for the Three Months ended March 31, 2002 and March 31, 2001 5 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements (Unaudited) 6 Item 2. -

ANDY D'addario Re-Recording Mixer

ANDY D'ADDARIO Re-Recording Mixer SOUNDTRACK (PILOT) Joshua Safran Netflix RRM SSE, CRAZY BITCHES Jane Clark FilmMcQueen RRM THE INBETWEEN (2 EPISODES, RRM Moira Kirland NBC SEASON 1) Stephanie Savage/Josh RRM DYNASTY The CW Schwartz THE X FILES Chris Carter Fox Network RRM SSE, BLURT (TV MOVIE) Michelle Johnston Pacific Bay Entertainment RRM MOZART IN THE JUNGLE Alex Timbers Amazon RRM Image not found or type unknown ESCAPE FROM MR. SSE, LEMONCELLO'S LIBRARY (TV Scott McAboy Nickelodeon Network RRM MOVIE) TRANSPARENT Jill Soloway Amazon RRM KINGDOM Byron Balasco DirectTV RRM I LOVE DICK (6 EPISODES, RRM Sarah Gubbins Amazon Studios SEASON 1) IMPOSTERS Paul Adelstein Bravo! RRM SSE, RUFUS-2 (TV MOVIE) Savage Steve Holland Nickelodeon Network RRM LEGENDS OF THE HIDDEN SSE, Joe Menendez Nickelodeon Network TEMPLE (TV MOVIE) RRM SSE, LIAR, LIAR, VAMPIRE (TV MOVIE) Vince Marcello Nickelodeon Network RRM SSE, ONE CRAZY CRUISE (TV MOVIE) Michael Grossman Nickelodeon Network RRM SSE, SPLITTING ADAM (TV MOVIE) Scott McAboy Nickelodeon Network RRM SSE, SANTA HUNTERS (TV MOVIE) Savage Steve Holland Nickelodeon Network RRM A FAIRLY ODD SUMMER (TV SSE, Savage Steve Holland Nickelodeon Network MOVIE) RRM HAWAII FIVE-O Peter M. Lenkov CBS RRM SWINDLE (TV MOVIE) Jonathan Judge Nickelodeon Network RRM Formosa Broadcast www.FormosaGroup.com/Broadcast 323.853.0008 [email protected] Page 1 GOLDEN BOY (PILOT) Nicholas Wootton CBS RRM CSI: NY Ann Donahue CBS RRM SECOND SIGHT (TV MOVIE) Michael Cuesta CBS RRM A FAIRLY ODD CHRISTMAS (TV RRM Savage Steve -

Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Winter 12-19-2019 Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics Kendra Hansen [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the American Studies Commons, Education Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hansen, Kendra, "Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 239. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/239 This Project (696 or 796 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Curriculum for TEFL 107: American Childhood Classics A Plan B Project Proposal Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Kendra Rose Hansen In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language December, 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota Copyright 2019 Kendra Rose Hansen v Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my family. To my husband, Brian Hansen, for supporting me and encouraging me to keep going and for taking on a greater weight of the parental duties throughout my journey. To my children, Aidan, Alexa, and Ainsley, for understanding when Mom needed to be away at class or needed quiet time to work at home. -

Happily Ever Ancient

HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT This work is subject to an International Creative Commons License Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0, for a copy visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media First Edition, December 2020 ...still facing COVID-19. Editor: Asociación para la Investigación y la Difusión de la Arqueología Pública, JAS Arqueología Plaza de Mondariz, 6 28029 - Madrid www.jasarqueologia.es Attribution: In each chapter Cover: Jaime Almansa Sánchez, from nuptial lebetes at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Greece. ISBN: 978-84-16725-32-8 Depósito Legal: M-29023-2020 Printer: Service Pointwww.servicepoint.es Impreso y hecho en España - Printed and made in Spain CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: A CONTEMPORARY ANTIQUITY FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG AUDIENCES IN FILMS AND CARTOONS Julián PELEGRÍN CAMPO 1 FAMILY LOVE AND HAPPILY MARRIAGES: REINVENTING MYTHICAL SOCIETY IN DISNEY’S HERCULES (1997) Elena DUCE PASTOR 19 OVER 5,000,000.001: ANALYZING HADES AND HIS PEOPLE IN DISNEY’S HERCULES Chiara CAPPANERA 41 FROM PLATO’S ATLANTIS TO INTERESTELLAR GATES: THE DISTORTED MYTH Irene CISNEROS ABELLÁN 61 MOANA AND MALINOWSKI: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH TO MODERN ANIMATION Emma PERAZZONE RIVERO 79 ANIMATING ANTIQUITY ON CHILDREN’S TELEVISION: THE VISUAL WORLDS OF ULYSSES 31 AND SAMURAI JACK Sarah MILES 95 SALPICADURAS DE MOTIVOS CLÁSICOS EN LA SERIE ONE PIECE Noelia GÓMEZ SAN JUAN 113 “WHAT A NOSE!” VISIONS OF CLEOPATRA AT THE CINEMA & TV FOR CHILDREN AND TEENAGERS Nerea TARANCÓN HUARTE 135 ONCE UPON A TIME IN MACEDON. -

Hourglass 10-05-05 .Indd

GGotot tthehe bblues?lues? — PPageage 6 ((ArianaAriana JJohnson,ohnson, 99,, hhelpselps JJabkiekabkiek JJibkeibke wweaveeave a matmat aatt tthehe ManitManit DayDay ccelebrationelebration SaturdaySaturday aatt GGeorgeeorge SSeitzeitz EElementarylementary SSchool.chool. FForor mmore,ore, sseeee PPageage 44.).) ((PhotoPhoto bbyy EElizabethlizabeth DDavie)avie) www.smdc.army.mil/KWAJ/Hourglass/hourglass.html Commentary Be careful what you wish for, it might come true Russian President Vladimir Putin Many believe the defeat in Afghani- recently said the breakup of the stan started the Soviet Union on the Soviet Union was the worst tragedy downward spiral to its breakup in 1991. in the history of mankind. Afterwards, Afghanistan, Ubekistan, His statement was met with ridi- Tajikistan and the other ‘stans’ that cule, disbelief and scorn around the had been under Soviet control became world. havens for Islamic fundamentalists and How could the end of the “evil extremists. empire” be a bad thing? So it seems all that support to the But maybe, he knew what he was talking about. mujahadeen has come back to bite us in the behind During the Cold War, as dark as those days were, ter- doesn’t it? You almost have to ask if it would have been rorism was sporadic at best. Most of it took place in Israel better for the world if we hadn’t helped the mujahadeen and since a lot of countries disliked Israel, it didn’t raise and the Soviets had won the war and controlled that wild, much of a stink. Of course, there was the Irish Repub- mountain country and its tribes and warlords? Maybe lican Army in Northern Ireland who sometimes planted even captured or killed Bin Laden? bombs in London, but for most of the world, terrorism If the Soviet Union still existed, would we actually be wasn’t much of a blip on the radar screen. -

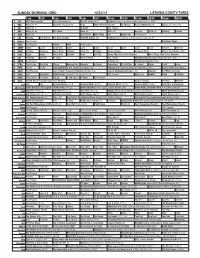

Sunday Morning Grid 12/21/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/21/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Kansas City Chiefs at Pittsburgh Steelers. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Young Men Big Dreams On Money Access Hollywood (N) Skiing U.S. Grand Prix. 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. Outback Explore 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Atlanta Falcons at New Orleans Saints. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Christmas Angel 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Alsace-Hubert Heirloom Meals Man in the Kitchen (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Christmas Twister (2012) Casper Van Dien. (PG) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Children's DVD Titles (Including Parent Collection)

Children’s DVD Titles (including Parent Collection) - as of July 2017 NRA ABC monsters, volume 1: Meet the ABC monsters NRA Abraham Lincoln PG Ace Ventura Jr. pet detective (SDH) PG A.C.O.R.N.S: Operation crack down (CC) NRA Action words, volume 1 NRA Action words, volume 2 NRA Action words, volume 3 NRA Activity TV: Magic, vol. 1 PG Adventure planet (CC) TV-PG Adventure time: The complete first season (2v) (SDH) TV-PG Adventure time: Fionna and Cake (SDH) TV-G Adventures in babysitting (SDH) G Adventures in Zambezia (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: Christmas hero (SDH) NRA Adventures of Bailey: The lost puppy NRA Adventures of Bailey: A night in Cowtown (SDH) G The adventures of Brer Rabbit (SDH) NRA The adventures of Carlos Caterpillar: Litterbug TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Bumpers up! TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Friends to the finish TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Top gear trucks TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: Trucks versus wild TV-Y The adventures of Chuck & friends: When trucks fly G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (CC) G The adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad (2014) (SDH) G The adventures of Milo and Otis (CC) PG The adventures of Panda Warrior (CC) G Adventures of Pinocchio (CC) PG The adventures of Renny the fox (CC) NRA The adventures of Scooter the penguin (SDH) PG The adventures of Sharkboy and Lavagirl in 3-D (SDH) NRA The adventures of Teddy P. Brains: Journey into the rain forest NRA Adventures of the Gummi Bears (3v) (SDH) PG The adventures of TinTin (CC) NRA Adventures with -

Sunday Morning, Nov. 1

SUNDAY MORNING, NOV. 1 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 VER COM Good Morning America (N) (cc) KATU News This Morning - Sun (cc) 57642 NASCAR Countdown (Live) 19081 NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup: Amp Energy 500. (Live) 156028 2/KATU 2 2 85536 Paid 44791 Paid 46062 CBS News Sunday Morning (N) (cc) (TVG) 77739 Face the Nation The NFL Today (Live) (cc) 60739 NFL Football Denver Broncos at Baltimore Ravens. (Live) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (N) (TVG) 78062 766284 Newschannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Newschannel 8 at 7:00 (N) (cc) 60130 Meet the Press (N) (cc) 55807 Paid 55710 Paid 83994 Running New York City Marathon. 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) 35212 (Same-day Tape) (TVPG) 18505 Betsy’s Kinder- Make Way for Mister Rogers Dinosaur Train Thomas & Friends Bob the Builder Rick Steves’ Travels to the Nature Cloud: Challenge of the Silent Invasion: An Oregon Field 10/KOPB 10 10 garten 80517 Noddy 97710 20536 (TVY) 32371 29333 (TVY) 28604 Europe 42284 Edge 73642 Stallions. (TVPG) 38555 Guide Special (cc) (TVG) 18791 FOX News Sunday With Chris Wallace Good Day Oregon Sunday (N) 11888 Fox NFL Sunday (Live) (cc) (TVPG) NFL Football Seattle Seahawks at Dallas Cowboys. (Live) (cc) 12/KPTV 12 12 (cc) (TVPG) 74468 84333 395710 Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting Turning Point Day of Discovery In Touch With Dr. Charles Stanley Paid 42826 Paid 57246 Paid 94888 Paid 31710 Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 22/KPXG 5 5 63994 29062 (TVG) 48197 (cc) (TVG) 927284 282623 Jentezen Franklin Dr. -

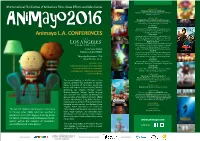

Programa Animayo La

XI International Film Festival of Animations Films, Visual Effects and Video Games 16:00 to 16:30 Painting in real time with Bill Recino (Animator in Beauty and the beast, Mulan, Litle Mermaid, Aladdin), in live show. 16:30 to 17:30 “Bringing life to your animations with voiceover.” Voice performance is a key component that helps bring an animated project to life, literally the very soul of its characters. Animayo2016 René Veilleux. Casting director and voice director for Verite Voiceover "Elder Scrolls Online", "Monster High", "The Snow Queen", "Cloud Bread" and "Monsuno". Animayo L.A. CONFERENCES Larry Huber. Veteran Animation Producer who’s credits include "Fish Police", "Danger Rangers", and "ChalkZone" and Executive Producer of "What A Cartoon" and "Random Cartoons". Barbara Goodson. Created the voice of "Mother Talzin" in Star Wars: The Clone Wars, "Kyla Mex & Clauda" in Star Trek Online, "Lady Vashj and Alexstrasza" in World of Warcraft, "Empress Rita 6363 Sunset Blvd. Repulsa" en la Mighty Morphin Power Ranger’s TV series. Rick Zief. Hollywood, CA 900028 Voice actor on numerous series including "The Tom and Jerry Show", "Get Blake" and "Olivia". Also successful voice Thursday November 17th and casting director on numerous projects including "Steamboy". Main Theatre 16:00 Audu Paden. Animation Producer and Director who’s credits include Exclusive in LA: "Monster High", "Animaniacs", "Stuart Little 3", "Rugrats", and Internatonal awards Animayo 2016. "The Simpsons". Jeremy Adams. The best short films of animaton, Screenwriter "Green Lantern the Animated Series", "Thun- commercials, videoclips, cinematc derbirds are Go!" and "Justice League Action". and visual effects. 17:45 to 18:45 "Modeling in an Animation Pipeline " Abrahan Meneu Character Modeler in Dreamworks The annual meetng of the Festval in Gran Animation. -

Nickelodeon Singapore : Program Schedule 1 - 4 January 2009 (R1)

NICKELODEON SINGAPORE : PROGRAM SCHEDULE 1 - 4 JANUARY 2009 (R1) Thu Friday Sat Sun SIN SIN 1-Jan 2-Jan 3-Jan 4-Jan 6:00 Go Diego, Go 6:00 6:15 Hey Arnold 6:15 6:30 The Fairly OddParents 6:30 7:00 Nick JR: The Backyardigans Nick JR: Blue's Clues 7:00 7:30 Nick JR: Hi-5 Nick JR: Hi-5 7:30 8:00 Nick JR: Yo Gabba Gabba! Nick JR: Go, Diego, Go 8:00 8:30 Nick JR: Go, Diego Go! Nick JR: Dora, the Explorer 8:30 9:00 Nick JR: WonderPets Tak & the Power of Juju 9:00 9:15 New Year Special: Dora Dances to the Rescue (9-10am) Nick JR: The Magic Roundabout 9:30 Nick JR: Dora, the Explorer The Fairly OddParents 9:30 10:00 Frankenstein's Cat 10:00 Upsized: The Fairly OddParents 10:30 Drake & Josh 10:30 11:00 Edgar & Ellen The Naked Brothers Band 11:00 11:30 New Year Special: Holidaze El Tigre 11:30 11:45 The Mighty B! Upsized: SpongeBob SquarePants 12:00 Ricky Sprocket 12:00 12:30 New Year Special: Team Galaxy : Predators from Outer Lola & Viginia Chalkzone 12:30 12:45 Space Frankenstein's Cat 13:00 SpongeBob SquarePants 13:00 Upsized: Danny Phantom 13:30 The Fairly OddParents 13:30 14:00 Edgar & Ellen 14:00 Upsized: The Fairly OddParents 14:30 The Adventures of Jimmy Neutron 14:30 15:00 The Fairly OddParents The Naked Brothers Band 15:00 15:30 El Tigre Zoey 101 15:30 15:45 The Mighty B! 16:00 Avatar, the Legend of Aang 16:00 Upsized: SpongeBob SquarePants 16:30 TEENIck: iCarly 16:30 17:00 TEENick: Drake & Josh El Tigre 17:00 17:30 Danny Phantom 17:30 Upsized: The Fairly OddParents 18:00 SpongeBob SquarePants 18:00 18:30 Grossology 18:30 Nicktoons: SpongeBob